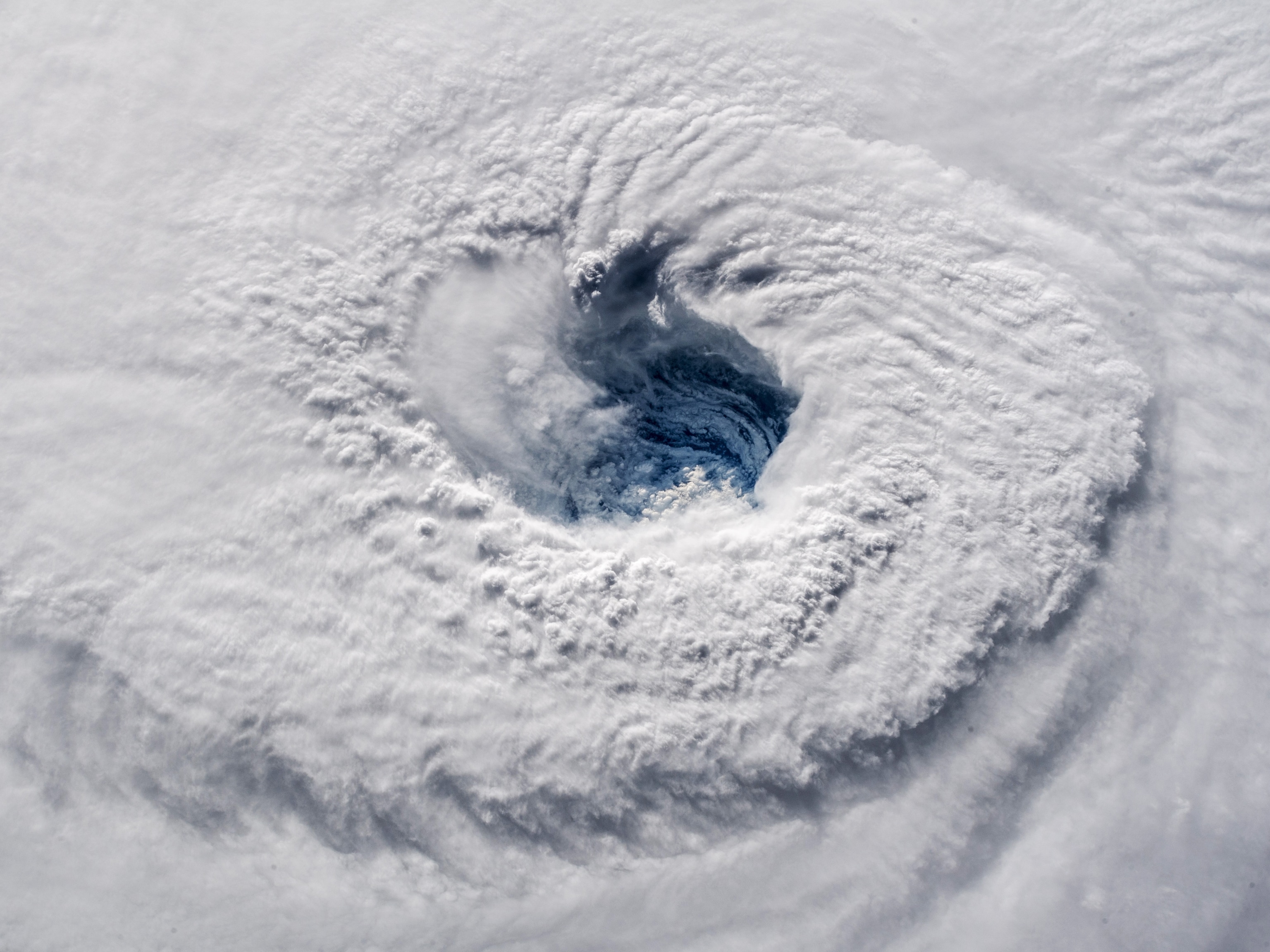

Hurricane Laura struck the southwest coast of Louisiana with 150 mph winds early Thursday morning, but it was the prediction of an enormous storm surge, the powerful rush of ocean water moving inland, that had National Hurricane Center officials warning that conditions would be “unsurvivable.”

The storm did indeed do terrible damage. Photos from East Texas and southwestern portions of Louisiana, which took the brunt of the storm, show entire neighborhoods torn apart by winds. A hurricane-damaged chemical plant near Lake Charles caught fire Thursday, sending clouds of chlorine into the air; the cause of the fire is unclear.

But in an early morning interview with CNN, Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards said the storm surge had turned out not to be as dangerous as the 15-foot—or higher—waves that had been predicted. Now downgraded to a tropical storm, Laura is moving away from Louisiana and heading toward the East Coast.

It may be days until the exact levels of the storm surge can be calculated, says Jamie Rhome, the leader of the National Hurricane Center’s storm surge prediction team. It had been forecast to extend nearly 40 miles north of the coast, but aerial video will be needed, Rhome says, to see exactly how far inland the waves reached. At least one surge monitoring station was damaged, and others only collect and store data instead of reporting it in real time.

Early models suggest parts of Cameron Parish saw surges 10 to 20 feet high, but Rhome says that remains to be confirmed. In East Texas, a storm surge predicted to push tides as much as 10 feet higher was closer to three, reports the Associated Press. Parish officials in Jefferson, and Lafourche to the west of it, say the storm surge caused some street flooding but no major damage.

While the storm surge has not yet met its deadly expectations—there have been four known fatalities so far—Rhome says warnings are intentionally dire to encourage evacuations.

“Storm surge is typically the leading cause of death in a hurricane,” he says, “And [the warning] was meant to help people struggling with the decision to evacuate.”

A number of factors made Laura’s predicted storm surge potentially treacherous for Louisiana. This is how experts calculated the storm’s risk and why predictions aren’t exact. (Find out why storm surges can be so dangerous.)

An imperfect science

Storm surges are pretty much what they sound like—sudden surges of ocean water moving inland during storms that can be 30 feet high and stretch tens of miles inland, swelling rivers, lakes, and streams and causing catastrophic flooding.

Louisiana’s topography makes it particularly vulnerable to such an onslaught. Much of southern Louisiana is flat and carved into islands by rivers and bayous.

“Rivers are like a highway to allow storm surge to get further inland,” says Rhome.

Because a surge can move in so quickly and is historically so deadly, storm surge warnings display what’s called the “reasonable worst-case scenario.”

“It’s intentionally not the average. It’s the worst outcome,” says Brian McNoldy, a meteorologist at the University of Miami.

There are a number of variables that go into modeling what the storm surge might be: the size of the storm itself, the intensity of its winds, the speed at which it’s moving, and even the shape of the ocean floor influences how much water will be pushed onto land.

Researchers at the National Hurricane Center are continuously tweaking those variables in the days before the storm, changing the possible wind speeds, for example, to calculate different outcomes. Were they to run 100 different scenarios, explains McNoldy, an average of the worst ten outcomes would be issued as the storm surge warning. Anecdotally, the storm surge seen in parts of Texas and Louisiana seems to have been lower than the worst-case scenario predicted. But in order to get a final read on what the surge really was, and how accurate the predictions really were, researchers will need data from NOAA and the U.S. Geological Society tidal stations in the region. That will be collected over the coming weeks.

Forecasters nearly exactly predicted where Laura would come ashore, and while the surge may not have been as high as anticipated, McNoldy and Rhome say knowing exactly how a storm will evolve days in advance, and how big of a surge it will produce, is infeasible.

“It’s impossible to accurately forecast any chaotic system, and the atmosphere is a chaotic system,” says McNoldy.

Rhome expects any residual storm surge from Laura’s outer bands to wane Thursday, though flooding will likely remain an issue in southern portions of the state.

The parts of Cameron Parish that may have seen the worst storm surge are residential areas.

“It’s my hope that those people heeded our warnings and got out of there,” says Rhome.