Why double-jointed people are more likely to have health problems

The ability to extend your joints past their normal range of motion isn’t just a harmless party trick—you may be at risk for chronic pain and conditions like long COVID and POTS.

For most of her life, Jacqueline Luciano, a registered nurse who lives in Chicago, has experienced mysterious injuries and ailments, including a long list of sprains and tears; dizziness and fatigue; chronic headaches; and chronic pain. Pregnancy was especially brutal on her body—her joints felt so lax that her hips kept popping out of joint.

“A lot of this went underdiagnosed and undertreated,” Luciano says. “I just kept injuring myself at work.” Even in a desk job, the strain of sitting upright all day triggered disabling headaches. In late 2021, she developed long COVID and her condition deteriorated to the point that she was forced to leave work.

As Luciano would discover, most of her health issues, including her long COVID, could be traced back to the fact that she is hypermobile, or double-jointed. Luciano joins an increasingly visible group of people, including the singer-songwriter Billie Eilish and New York Times bestselling author Rebecca Yarros, who are speaking out about their struggles with hypermobility.

Hypermobility can look very different from person to person, whether it’s being able to contort their limbs into unusual positions or having joints that keep popping out of socket. This ability to extend a joint past its normal range of motion may be a harmless party trick for some—and even an advantage for dancers and gymnasts.

But for many others, hypermobility is a sign that their connective tissue is weak, leaving them vulnerable to a wide range of issues such as chronic pain and gastrointestinal disorders. Research is further proving that hypermobility puts you at greater risk for developing a number of chronic conditions, such as long COVID, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), myalgic encephalomyelitis chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), and mast-cell activation syndrome (MCAS).

(What is POTS? This strange disorder has doubled since the pandemic.)

“Connective tissue is everywhere in our body,” which explains why it can lead to these systemic symptoms, says Linda Bluestein, an integrative pain medicine physician and the host of the podcast Bendy Bodies with the Hypermobility MD.

Although researchers are still working on understanding the connection between these conditions, they are beginning to piece together the unexpected risks of hypermobility—and why viral infections may pose a particular danger.

What is hypermobility—and how common is it?

People with hypermobility can fall into a couple of different buckets: those with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) and those without.

“All people with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome are hypermobile, but not all hypermobile people have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome,” says Jessica Eccles, a faculty at Brighton and Sussex Medical School, whose research focuses on hypermobility.

Although EDS, which is a genetic condition, is thought to be relatively rare, having hypermobile joints is much more common, with an estimated 3 to 4 percent of the general population having general joint hypermobility. Even more people are thought to have partial hypermobility, whether it’s hypermobility of the arms and legs; or of specific joints.

(Is Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome really so rare—or is it misdiagnosed.)

People with EDS all experience symptoms varying from chronic pain and fatigue to digestive disorders. For people who don’t meet the criteria for EDS, however, their hypermobility can either be asymptomatic—i.e. totally harmless—or it can also be associated with a host of other issues.

“It’s not the hypermobility that is the problem, it’s the quality of the connective tissue that is the issue,” says Alissa Zingman, a physician and founder of P.R.I.S.M. Spine and Joint, which specializes in treating patients with connective tissue disorders. Zingman notes that hypermobility is often the first clue that something is different about a person’s connective tissue.

When someone has hypermobility and additional symptoms, they meet the criteria for hypermobility spectrum disorder, which shares a number of overlapping features with EDS. Indeed, Eccles says the distinction between the symptoms of these disorders “is arbitrary.” As research is showing, patients with these disorders experience similar levels of severity in their symptoms.

The unexpected risks of hypermobility

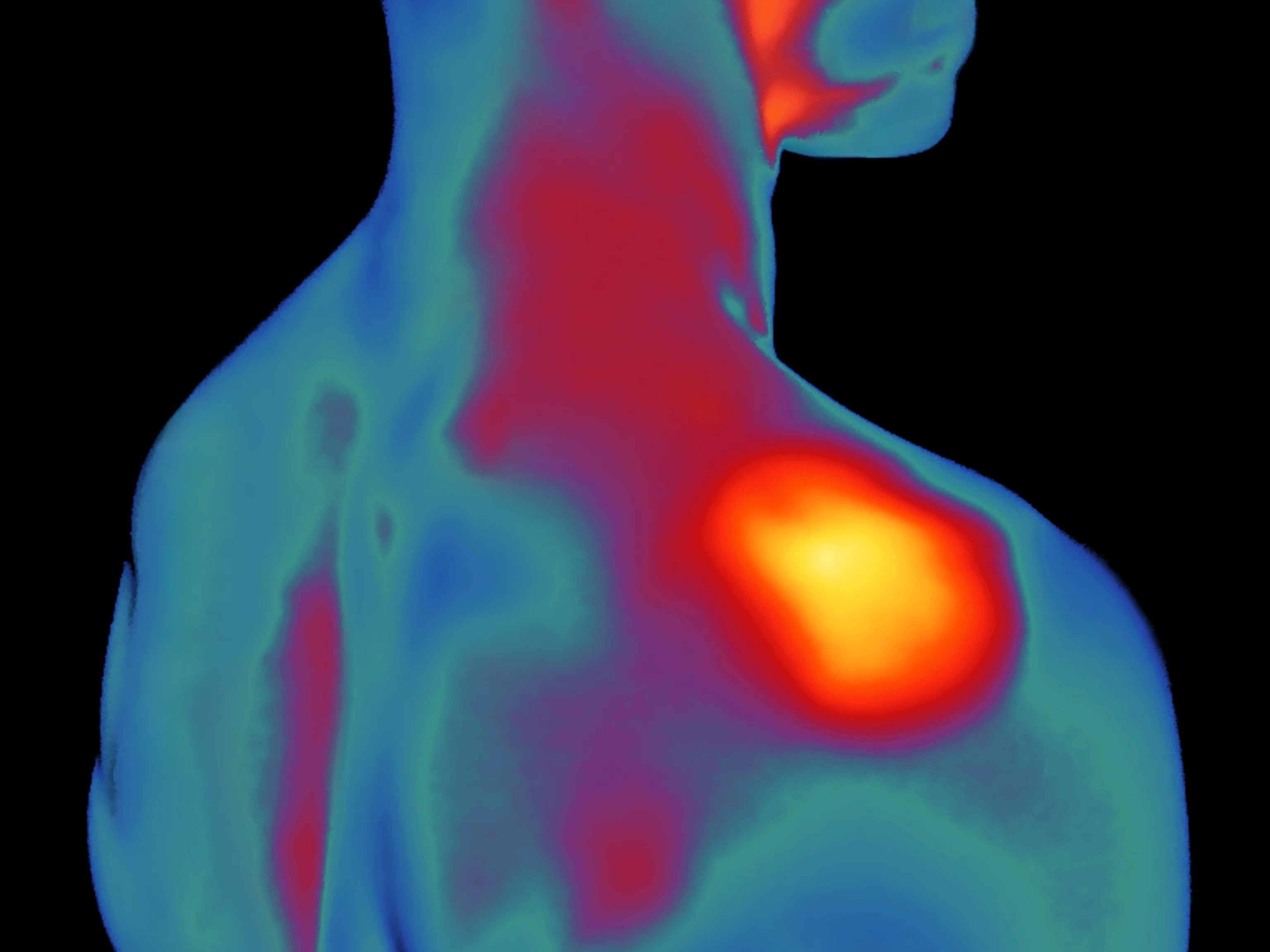

Hypermobility can show up in patients in diverse ways. For some, it can cause their muscles to lock up more than usual, as a countermeasure to help offset their joint instability and avoid injury. “That rigidity of the muscles helps to provide support,” says Clayton Powers, a physical therapist at the University of Utah, who specializes in treating patients with hypermobility and related disorders.

These countermeasures are often unconscious, and over time, they can take a toll. “Physically, they are having to compensate more,” says Jonathan Parr, a physical therapist and founder of Parr PT, which specializes in treating hypermobility and associated conditions. Some of the adverse effects they experience include tightness of the neck, spine and chest, as well as chronic headaches and pain.

Other lesser-known symptoms that are often associated with hypermobility include gastrointestinal issues, such as irritable bowel syndrome or unexplained vitamin deficiencies; symptoms that can be resolved by lying down, such as lightheadedness, palpitations or headaches; or excessive fatigue and brain fog.

For all of these issues, the cause can be traced back to the connective tissues in the associated organs. For example, the GI tract is a long tube made up of very thin connective tissue. Any weaknesses in that tissue may affect how effectively it breaks down food and absorbs nutrients into the body. Similarly, if the connective tissue that holds blood vessels together is a little stretchier than normal, then the blood vessels can’t pump enough blood into the brain, causing brain fog.

(Why does long COVID cause brain fog? Scientists may have an answer.)

“It’s a little different for each person,” says Bala Munipalli, an internal medicine physician at Mayo Clinic, who treats patients with long COVID.

Chronic inflammation is also often found in patients with hypermobility, along with other signs of immune system dysfunction, such as overactivation of mast cells, which are responsible for guarding the body against pathogens. As a result, hypermobility is often associated with immune system dysfunction, such as allergies, autoimmune disorders, or food intolerances. “Once one part of the immune system is dysregulated, there can be a cascade-type effect of immune dysfunction,” Zingman says.

Why viruses pose a particular danger

Patients with long COVID and related disorders, such as POTS or ME/CFS, often report a lot of seemingly unrelated symptoms—from constipation to a racing heart to brain fog to muscle aches.

However, the underlying cause of these diverse symptoms may not be as mysterious as it seems. “There’s a saying that “if the symptoms don’t connect, think connective tissue,’” says Powers.

Although we still don’t know exactly how viral infections damage connective tissue, there are a number of theories. For one, viral infections can trigger inflammation in the connective tissues, which “can lead to further damage to the connective tissue,” Munipalli says. Evidence suggests this can even trigger hypermobility in patients who didn’t have it previously, as well as worsen pre-existing hypermobility.

Another potential source of damage is the fact that a number of viruses, including herpes-viruses, Epstein-Barr Virus, and coronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 infections, can either damage collagen, which makes up connective tissue, or cause the body to produce less collagen.

(Is long COVID forever? A new study offers clues.)

“The viruses themselves will make collagenase, which is the enzyme that breaks down collagen,” says Jaime Seltzer, the scientific director of the nonprofit ME Action. “If somebody already has collagen that is a little loosey-goosey in the first place, there’s the potential for that person to be more susceptible to an infection-associated chronic illness.”

For Luciano, it took more than a year of dealing with long COVID symptoms before she was able to find a doctor who was familiar with the signs of hypermobility—and an even longer time to find a doctor that could formally diagnose her with hypermobile EDS. In the meantime, her symptoms have continued to worsen, to the point that she now has difficulty remaining upright.

Looking back, Luciano wishes that she had been diagnosed earlier so that she could have taken measures to keep from getting worse. She also wishes that her mother, who was disabled 30 years before her and may have also had undiagnosed EDS, had been able to receive the care she needed. “Thirty years later…it’s still the same,” Luciano says.