How much preventive medicine is too much?

High-tech solutions like full-body MRIs are the latest tools for detecting diseases like cancer. But delving too deep may not be appropriate for everyone.

Once the province of an aging population, today half of the thirty-four most common cancers are increasing among Generation X and Millennial populations, while nine of them, including colon cancer, are decreasing in adults over 65.

With cancer on the rise in a younger demographic, early detection is critical to recovery and longevity, as medical professionals across the board advise.

The most common procedure for identifying possible cancers are CT scans and X-rays that investigate concerning symptoms. They look for signs of tumors and other abnormalities in specific parts of the body. But what if the whole body could be scanned before symptoms even arise?

"Some of the fastest growing cancer categories—pancreatic, ovarian, colon in young people, lung in non-smokers—do not have standard screening programs. The current medical system’s approach is to wait until symptoms present, at which point many of these cancers have a poor prognosis," says Andrew Lacy, CEO of Prenuvo, a company opening full-body MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) clinics across the country. The company went viral last year after an Instagram post from Kim Kardashian called the scans, “life saving.”

Prenuvo is part of a growing trend of companies around the world promising better and more comprehensive preventative medicine—for a price.

In addition to full body MRIs, patients are seeking out extensive preventive exams by flying around the world for marathon medical check-ups. One viral TikToks showed a facility in Turkey where one woman received dental cleanings, blood tests, and a number of disease-detecting scans.

Doctors, however, remain skeptical that all this healthcare is worth it.

The American College of Preventive Medicine doesn’t recommend full body scans for people without symptoms. And as-is, only about five percent of Americans are up-to-date on existing preventative medical treatment options.

What can MRIs see in our bodies?

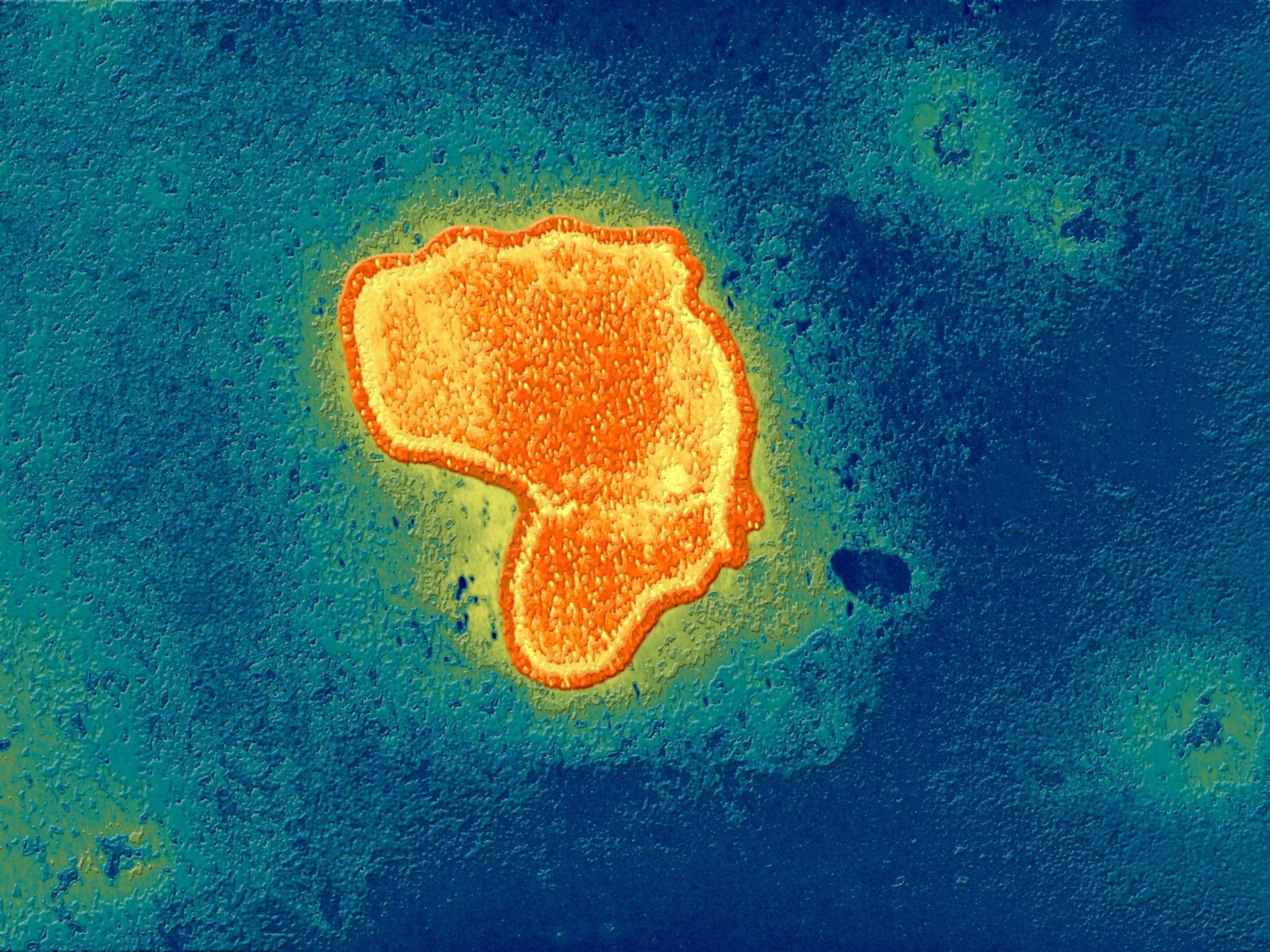

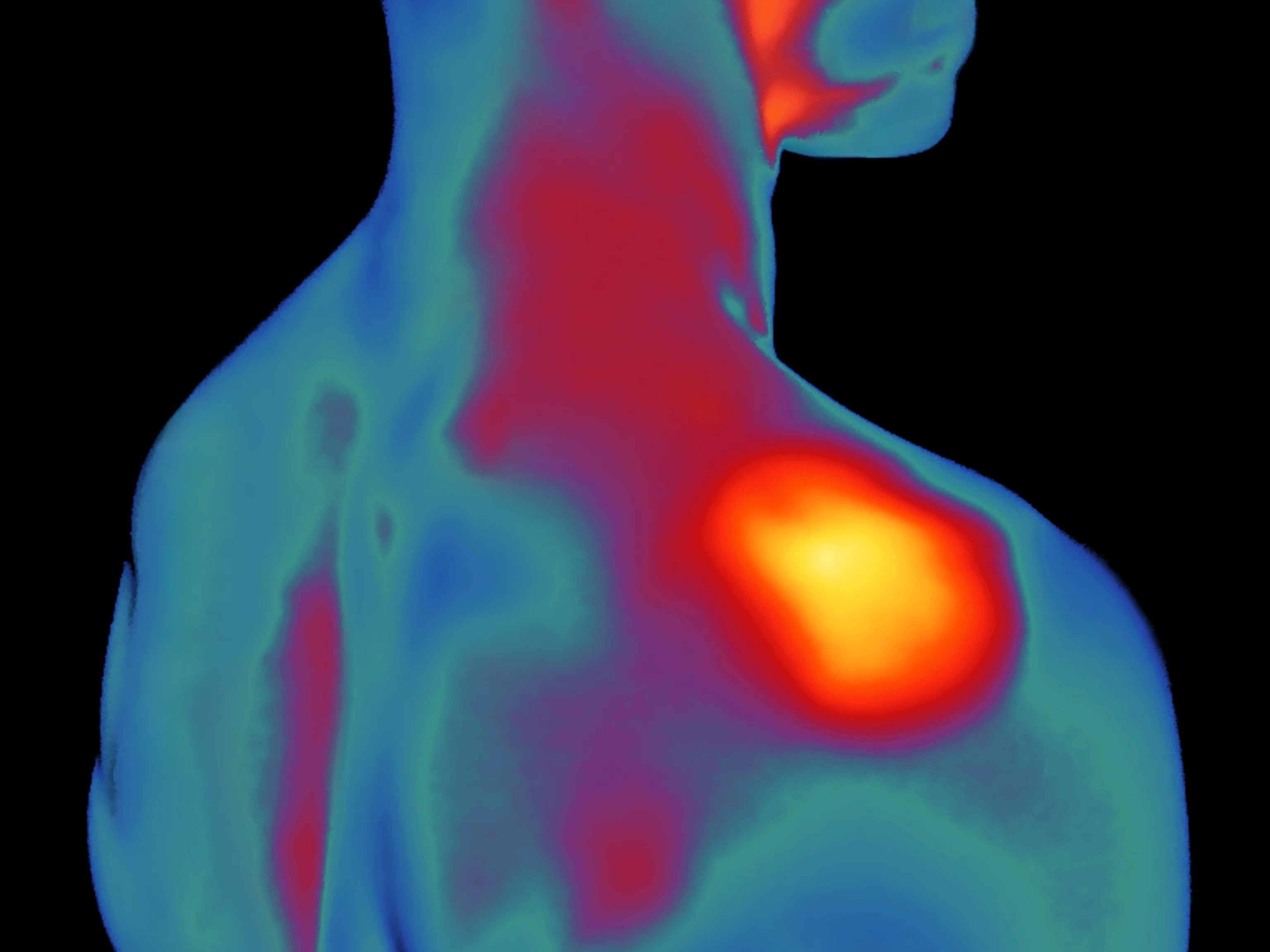

The value of an MRI is its ability to see deep into muscle, soft tissues, and bones for signs of tumors—an aberrant bundle of cells—and other abnormalities, such as aneurysms.

Patented in 1972 by physician Raymond Damadian, the MRI came to market in the 1980s to acclaim: Damadian had found a way for a machine to differentiate between cancerous cells and non-cancerous cells. Using a radiofrequency current, the protons in soft tissue and organs scatter; when the current is turned off they rearrange themselves.

The data returned in this process allows physicians to determine, in most cases, the difference between what’s normal and what’s not.

Imaging technologies such as MRIs can “tell us how healthy you are ahead of a disease,” says Bernardo Lamos, co-director of the Coit Center for Longevity & NeuroTherapeutics at the University of Arizona, whose work focuses on aging and the senior population. “And if you have knowledge [of a problem] you can intervene. There is an error rate for all of this, and you've got to be careful, but I certainly don't want to intervene too late.”

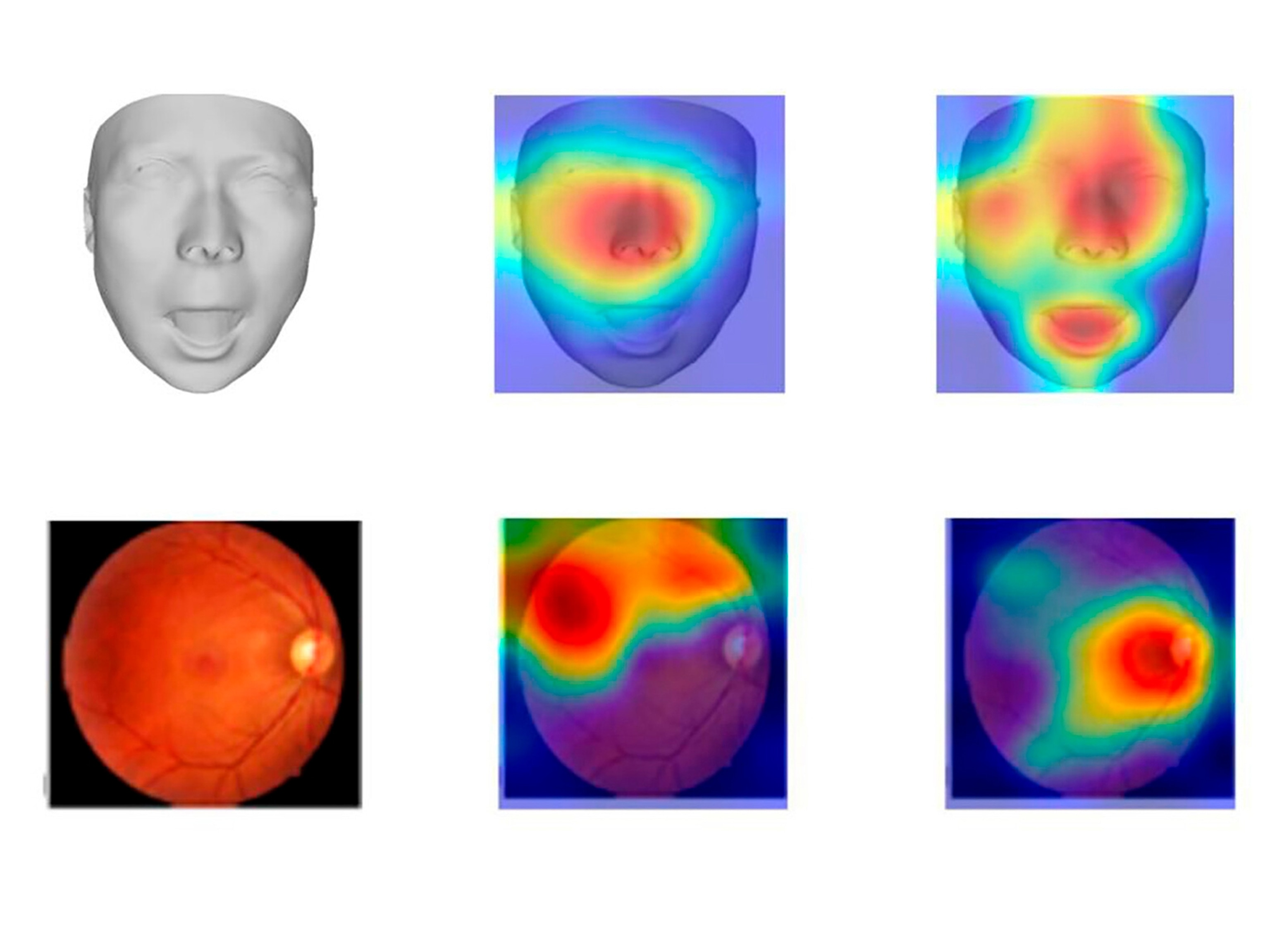

Ezra, a New York-based healthcare company, makes MRIs smarter and the final images sharper through its AI software. Like Pernuvo, Ezra has launched into full-body MRI services with clinics across the country, the latest in Austin, Texas, its "most requested city to date," according to the company's website.

Ezra's AI updates also reduce the time a person has to stay inside the MRI, down to 30 minutes from an hour.

(Do increased breast cancer screenings save lives? Doctors can't agree.)

Eric Verdin, president and CEO of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, has been getting a full-body MRI annually for the past five years and says these types of advanced imaging services can fill a critical gap in early detection. Only about 14 percent of cancers are found through standard preventive screening tests, according to research done by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago.

However those detection rates dramatically differed by the type of cancer detected. Prostate and breast cancers were detected by early screenings 77 and 61 percent of the time respectively, while preventive screening tests only detected three percent of lung cancer cases.

Not covered by insurance—unless prescribed by a doctor for a specific test—Verdin thinks the cost for a full-body MRI will drop over time. And insurers could jump on board as they have with, for example, mammograms.

“The quest is more about 'health span' than lifespan. It's about increasing our number of healthy years,” says Verdin.

(It's not your life span you need to worry about. It's your health span. Learn more.)

High costs and false positives

A 2023 study found that those who make more than $250,000 per year—that’s 15 million American households—were “far more likely to spend their time and money on their health."

As expensive as they are here—$1500–$2500 per scan—the bet is that more Americans will take the plunge.

Another major downside is that the AI-charged MRI scans will most likely record more anomalies—or "incidentalomas"—which are not medically concerning but can lead to additional, costly testing; unneeded and possibly dangerous surgical procedures; and unnecessary anxiety.

A study published in 2019 examined a dozen studies that weighed the pros and cons of providing full-body MRIs to patients with no discernable disease symptoms and found mixed results.

MRIs found abnormalities in just over a third of the people test, but it was unclear what the health risk of these abnormalities were. False positives were reported about 16 percent of the time.

These false positives or otherwise benign physical abnormalities can result in what physicians call “overdiagnosis.” Not unique to full-body MRIs, the burdens of overdiagnosis have been known for decades.

British neurosurgeon Richard Hayward famously coined what he termed the “acronym of our times”—VOMIT, or “victims of modern imaging technology.”