What causes multiple sclerosis—and why are women more at risk?

Millions worldwide suffer from this debilitating disease. Symptoms vary widely, and there’s no known cure.

On-screen, Christina Applegate moved audiences to fits of laughter as a cynical widow on Dead to Me, but off-screen, her toes started tingling. Within months, she was in a wheelchair, the actress revealed in a recent interview with ABC News. Then came her multiple sclerosis diagnosis.

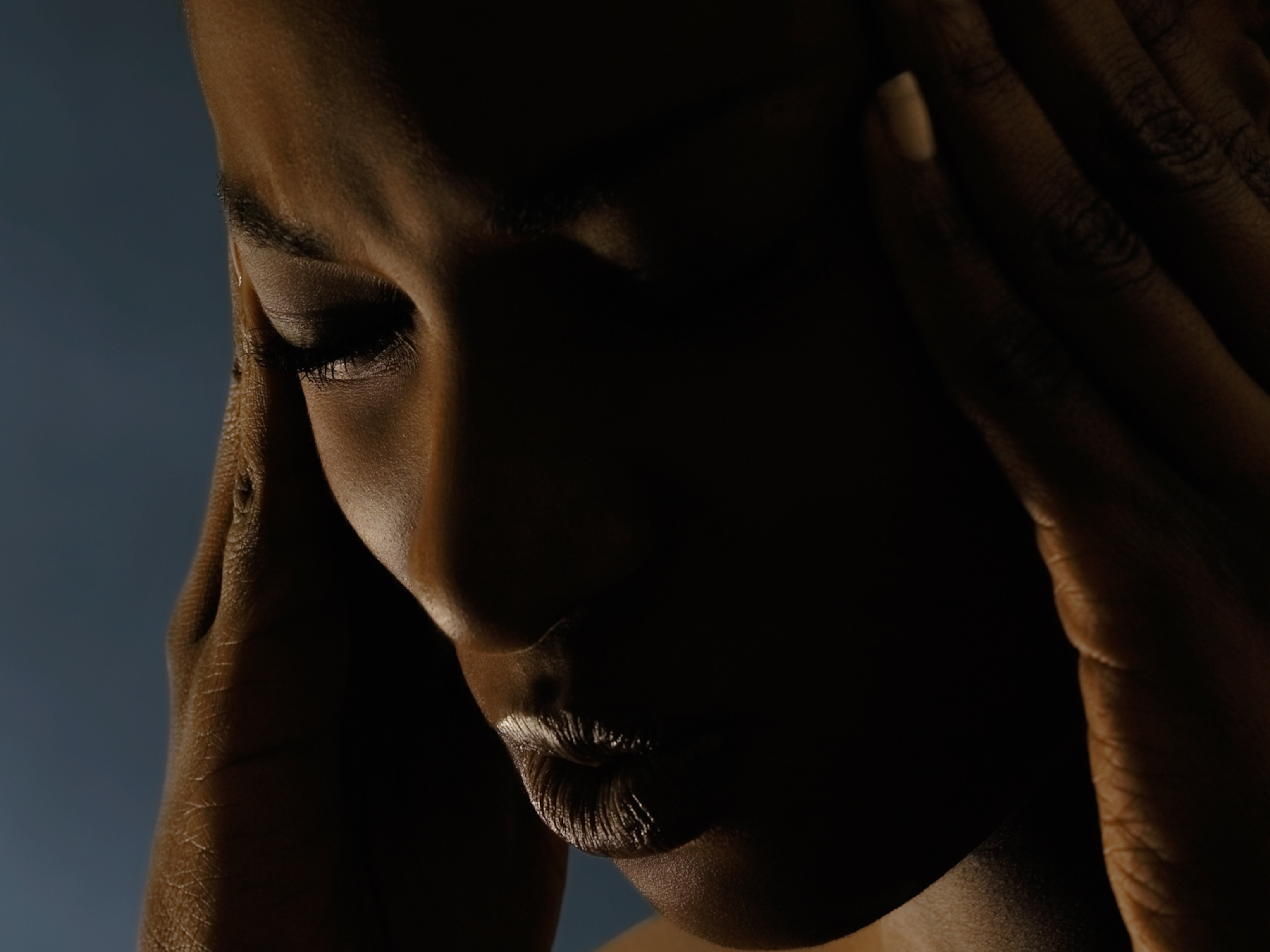

But Applegate’s symptoms didn’t stop there. Lesions in her brain caused pain all over her body. She began to experience depression, too. “I don’t enjoy living…I don’t enjoy things anymore,” Applegate said on the June 4 episode of her podcast, MeSsy. “It feels really fatalistic,” she said.

Around 2.9 million people worldwide—roughly one million in the United States—have multiple sclerosis or MS; Applegate and The Sopranos star Jamie-Lynn Sigler are two of them. In their podcast, the actresses speak candidly about their experiences with the disease.

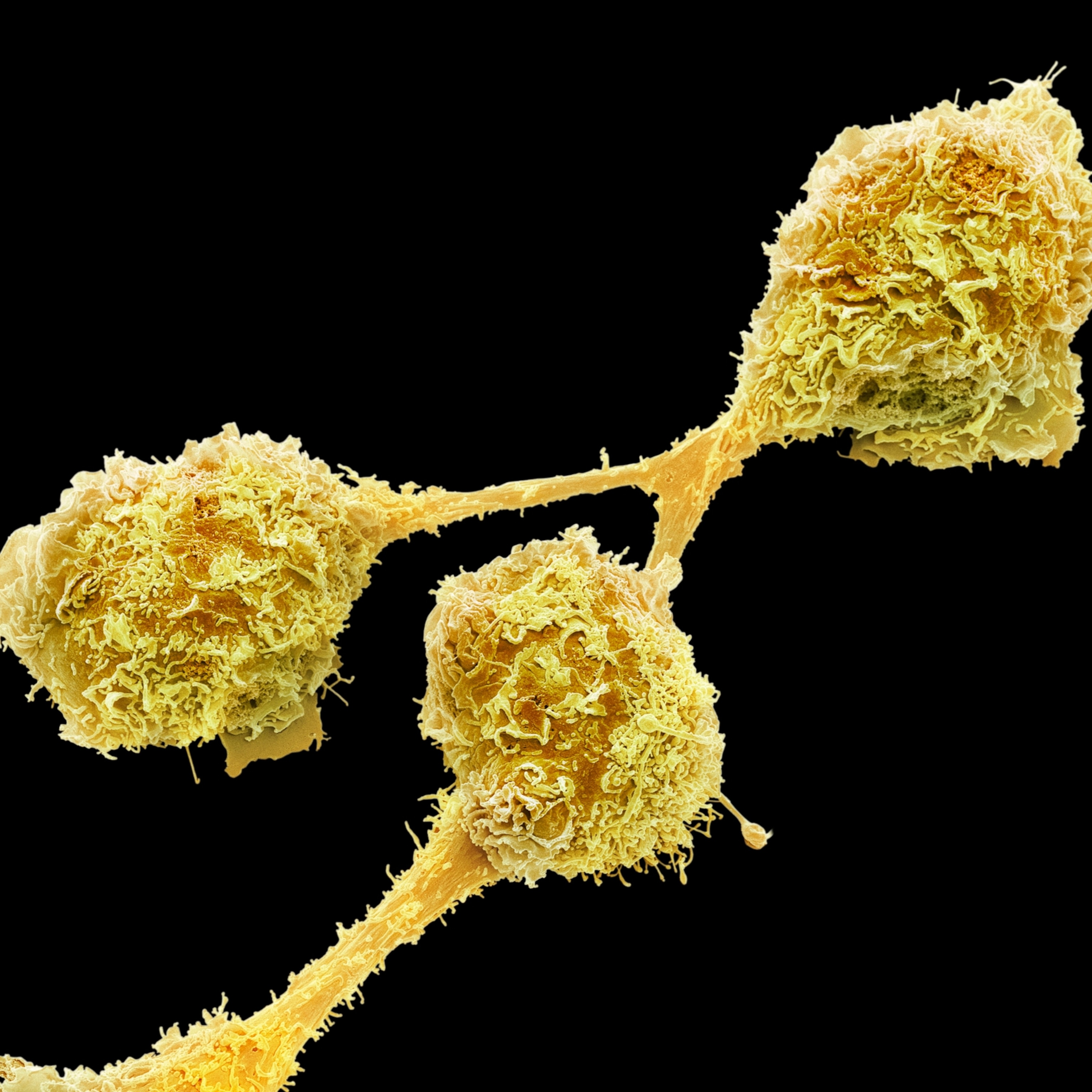

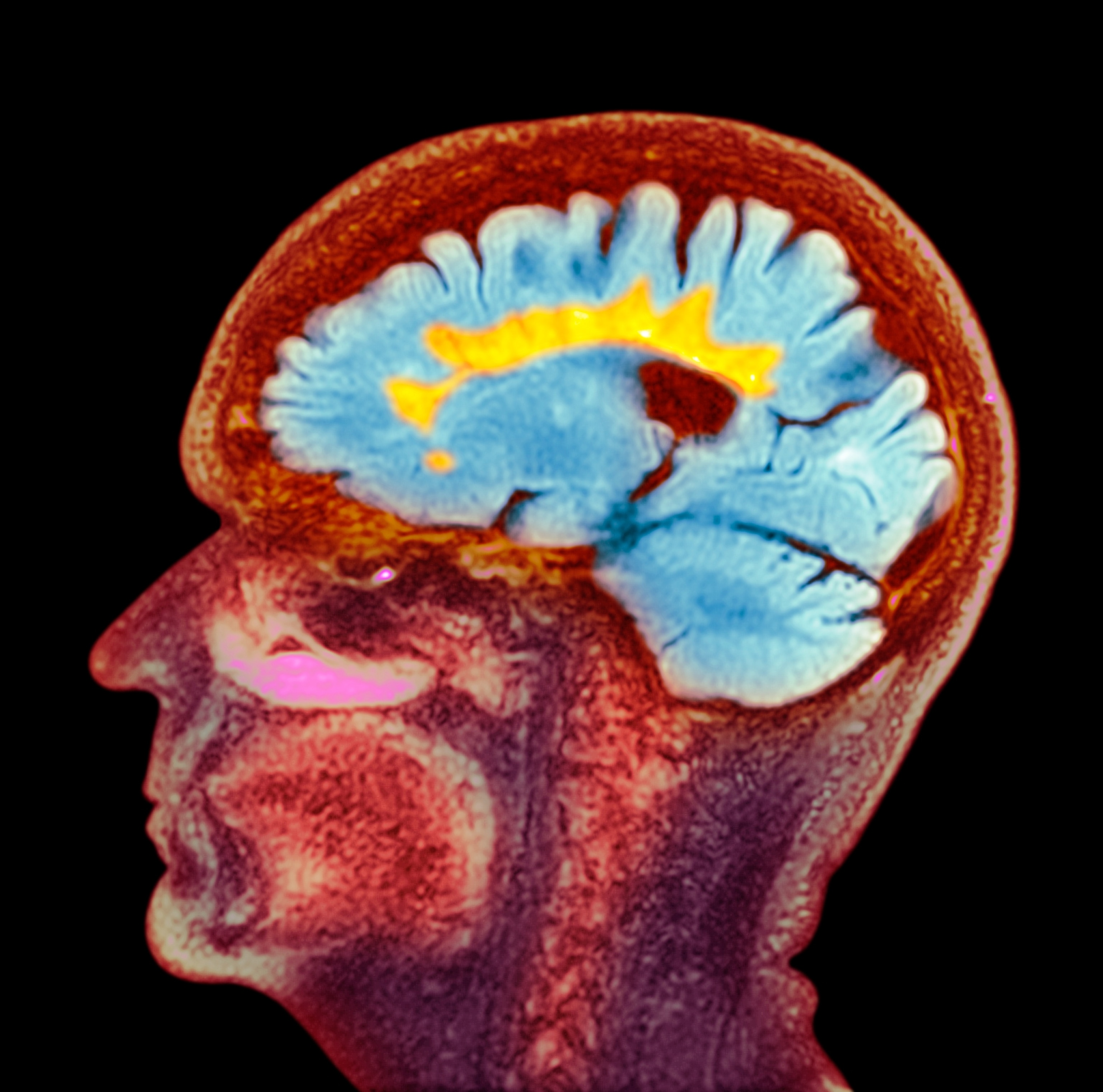

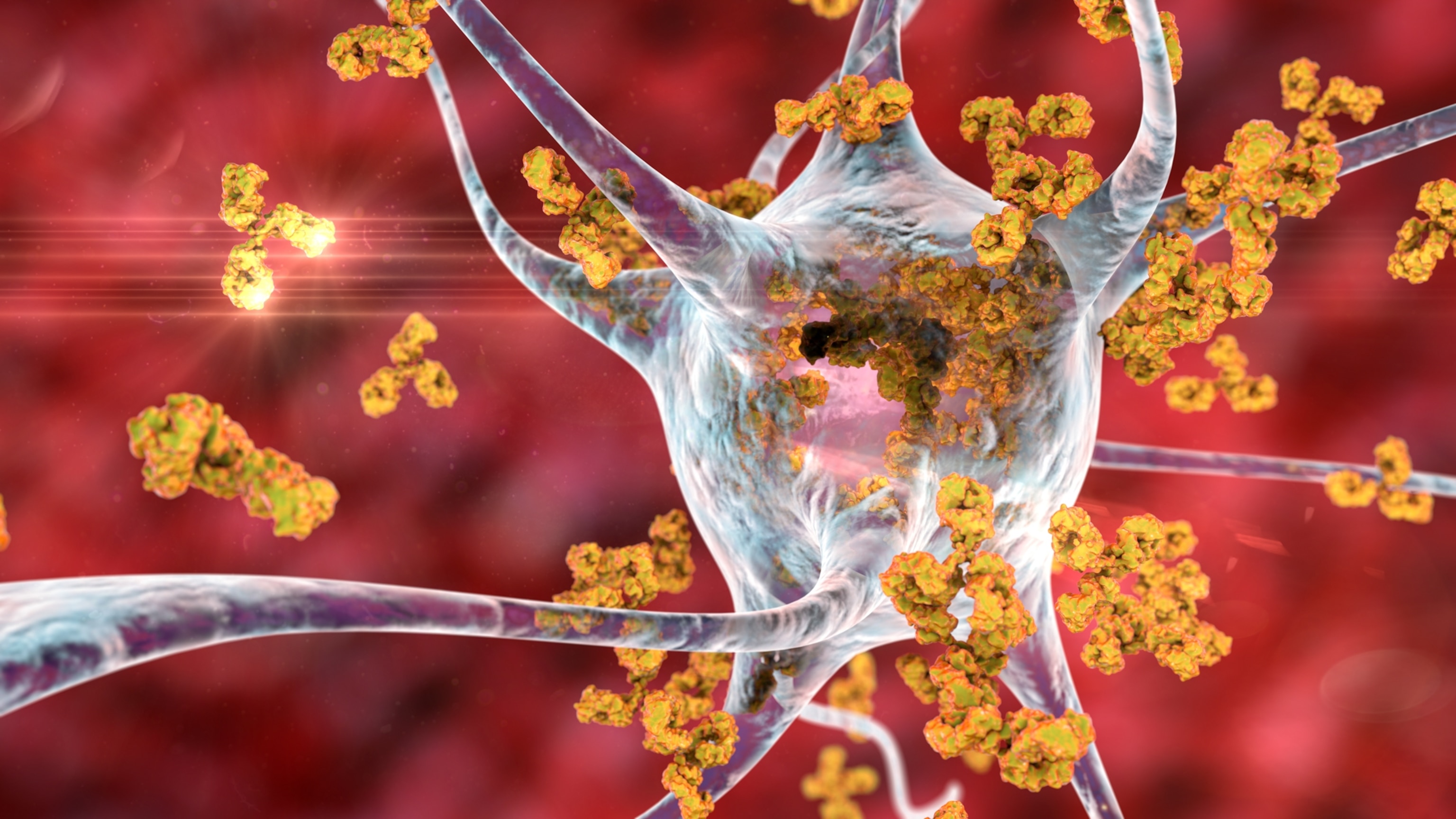

MS affects the central nervous system, the brain and spinal cord. The immune system attacks sheaths of a material called myelin that surround nerve fibers. Like insulation on wires, myelin protects nerves and helps transmit signals. But when myelin deteriorates, the nerve fibers underneath are exposed. This disrupts the brain’s communication and leaves behind lesions, which can cause a myriad of symptoms as the disease progresses.

But even several years before intense symptoms develop, the nervous system may already be under fire, says Riley Bove, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco. “[The symptoms don’t] quite make it to the threshold of someone going to the emergency room,” she says, but things might not feel quite right. There’s no definitive test for MS. Instead, the disease is diagnosed through clinical history and brain scans that reveal multiple lesions in different areas that formed at different times.

MS impacts individual people in unique ways. “If you’ve met one person with MS, then you’ve [only] met one person with MS,” explains Leigh Charvet, who directs MS research at New York University. Symptoms can vary widely, and much about the disease remains unknown. However, research is beginning to elucidate the disease's origins and potential treatments.

What are common symptoms of MS?

MS is often categorized as relapsing-remitting, where symptoms go away and come back, or progressive, where they continually get worse. But Bove says this is a false dichotomy. “Everyone experiences worsening symptoms because everybody is experiencing aging,” she says. As our bodies age, we lose muscle mass and strength. On top of that, MS patients experience accelerated aging, Bove says, exacerbating these losses. Instead of focusing on the relapsing versus progressive dichotomy, she says it’s more important to understand if the MS is active, where new lesions actively create symptoms.

These symptoms may include numbness, slurred speech, vision issues, and loss of coordination, but others are less detectable. So-called invisible symptoms, like fatigue and bladder dysfunction, are more common and difficult to treat, says Charvet. Because these symptoms are also harder for those without MS to see, “it’s a burden to get support and empathy,” says Bove.

Depression, like Applegate described, is common with MS, with around half of patients experiencing it at some point after diagnosis. Depression can be from a reaction to news of the disease, but evidence also suggests that other factors play a role, like damage to the brain, says María Gaitán, acting director of the Neuroimmunology Clinic at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Bethesda, Maryland.

What causes MS?

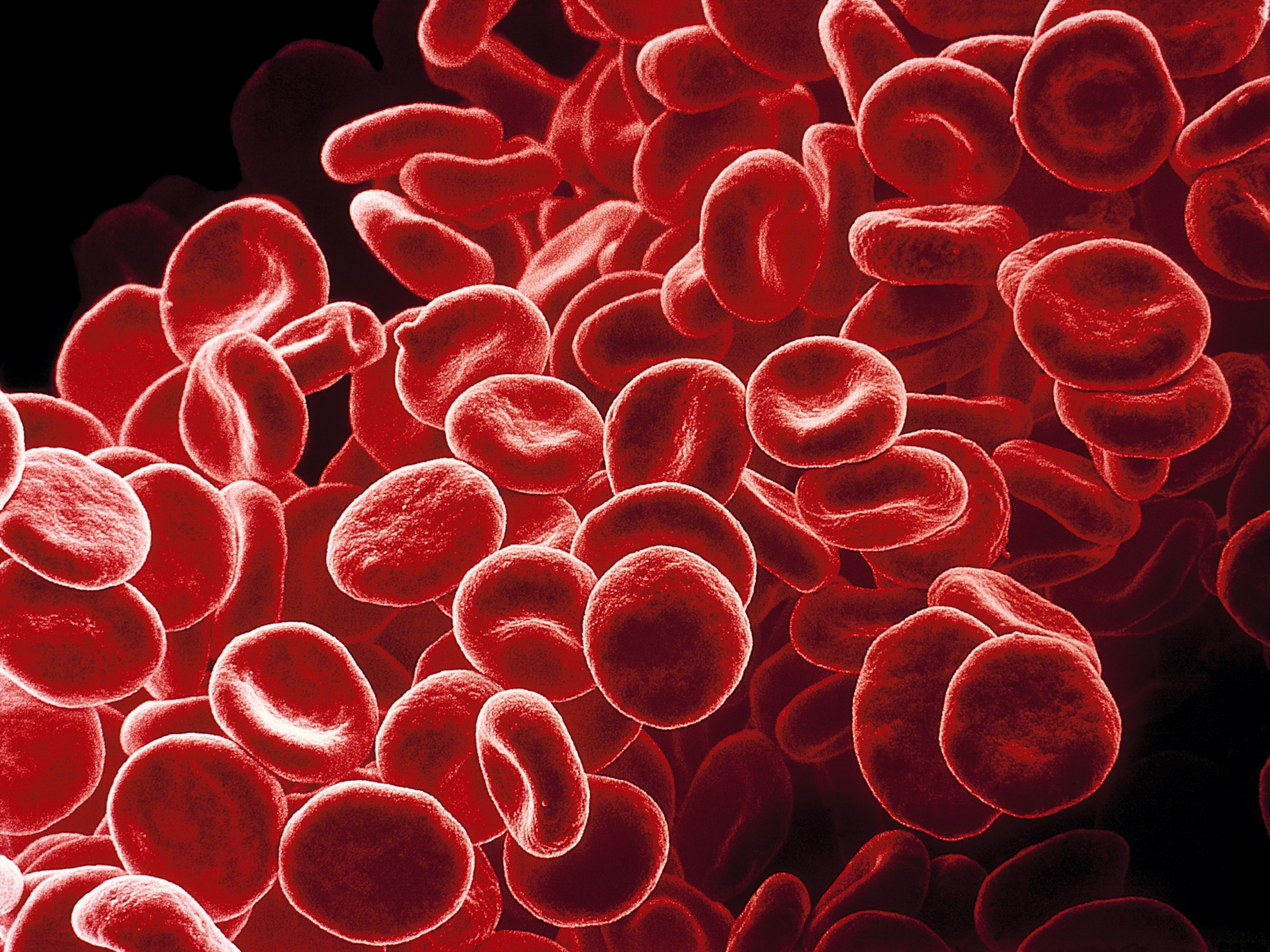

There’s no definitive cause of MS, but there is a prominent lead: the Epstein-Barr virus, known as EBV. In a study of over 10 million adults, the risk of developing MS increased by over 30 fold after EBV infection, researchers reported in Science back in 2022.

If you’re reading this, you’ve likely already been infected by EBV. The virus spreads through saliva, and “virtually everyone has EBV,” says Alberto Ascherio, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and an author of the study. But that’s not necessarily a cause for concern. The virus itself may be asymptomatic and fall dormant, and because about 90 percent of adults worldwide have had an EBV infection, the odds of developing MS remain about the same as the global average.

Ascherio likens the connection between the virus and MS to the connection between smoking and cancer. “Smoking causes lung cancer, but most smokers will never get lung cancer,” he says. So, EBV could cause MS, but most people infected with EBV won’t develop the disease. EBV may not be the one definitive cause of MS, but for now, it’s the leading culprit.

Who’s most at risk for MS?

Beyond EBV infections, other factors may increase the risk of MS. Women are about three times more likely to get MS, and scientists don’t know why. One theory is that women are more susceptible to autoimmune issues because of how responsive their immune systems must be to tolerate the foreign DNA of a fetus, Bove says. Sex chromosomes could also be related, but the answer “is definitely not as easy as ‘estrogen is good or bad,’” she says.

(Learn more about why women might be more at risk of developing autoimmune diseases.)

Blood relatives of those with MS are also more likely to develop the disease. This doesn’t mean MS is inherited, but genetic variants associated with it could be. Smoking, obesity and vitamin D deficiency are also associated with MS. Although MS can be diagnosed at any age, it is most often diagnosed in 20-, 30- and 40-year-olds.

Previously, MS was thought to primarily affect white women. Only in the last 10 or 15 years has the paradigm started to shift, reflecting what scientists know to be true: The disease develops across all racial groups, Bove says. Because of this lingering stereotype of MS, “a lot of people from different genders, races and ethnic backgrounds don't have the knowledge about MS in their communities, and that can be a barrier to getting help,” she says. While some areas of the world have relatively low MS cases, like sub-Saharan Africa, this may be more because of a lack of neurologists than a lack of MS, Bove says.

Prevention and treatment

There’s no known cure or way to guarantee you won’t develop MS. For now, limiting risks by quitting smoking, eating healthy and getting enough Vitamin D is the best prevention measure, Gaitán says, but they’re not surefire methods.

Researchers have identified blood markers for neuroinflammation, and in the future, tests for these markers could help diagnose MS or detect imminent flare-ups, allowing patients to take medication before symptoms arise.

Preventing EBV could also help. Vaccines for EBV are in early stages, and antivirals exist but have not seen much success in clinical testing. Ascherio believes MS cases could decrease significantly if an effective drug against EVB is developed.

For now, medications can treat symptoms and prevent new lesions, but none repair past damage to the nervous system. “That’s the next big thing on the horizon,” Charvet says.

Nothing is known to entirely prevent MS, but spreading awareness is an important step to catch the disease early. “Be aware of the disease and know that if you diagnose and treat early, you change the evolution of the disease,” Gaitán says.