Why looking at Earth from above is our most critical space mission

Climate scientist Michael Mann muses on seminal weather satellite NOAA-20—and what the perspective from space teaches us about our home.

Dear NOAA-20:

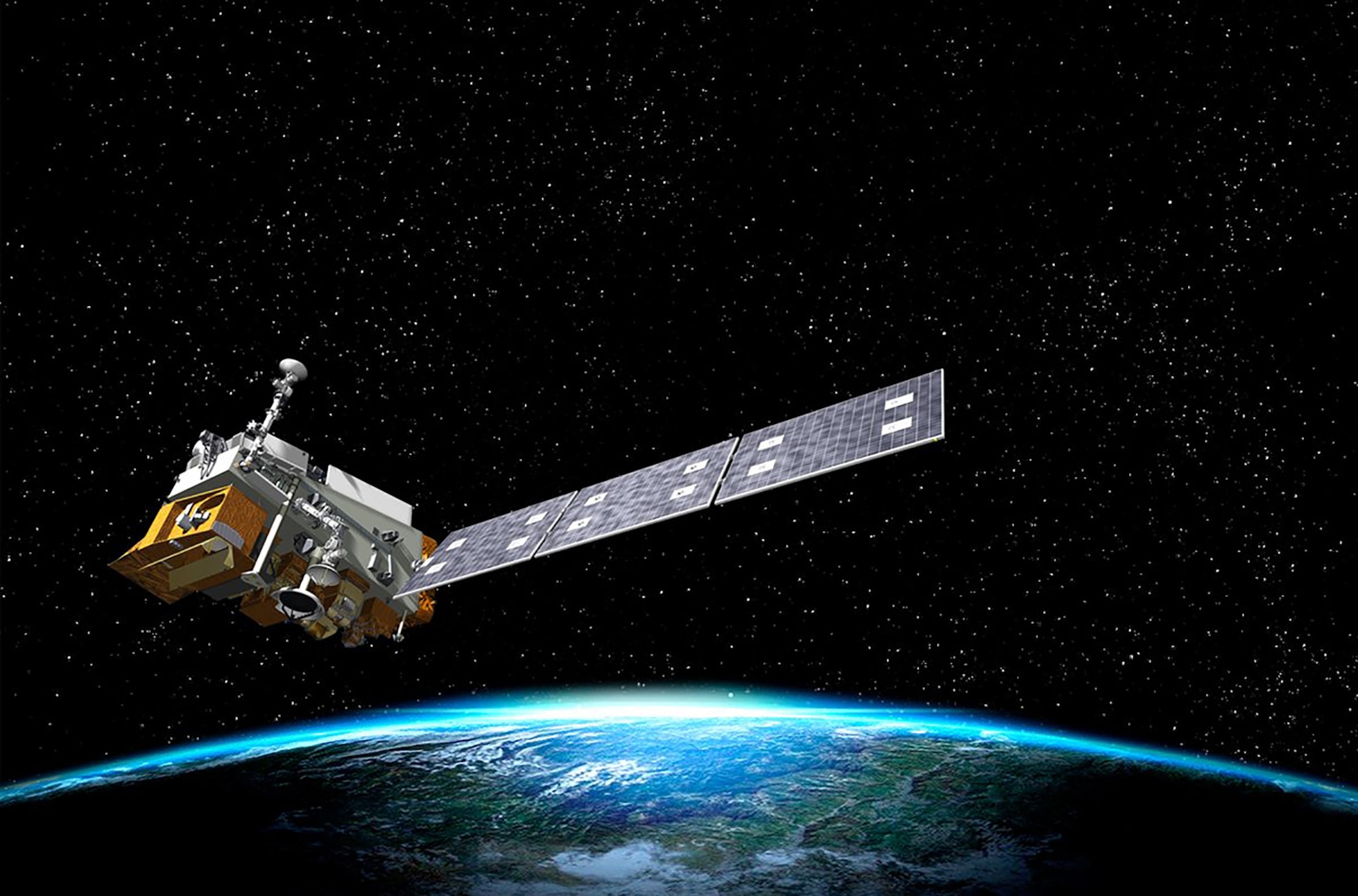

I know you don’t have a catchy name like Voyager or Cassini, but I appreciate you all the same. Unlike your extrovert cousins, you are an introvert—inward-looking, focused on just one planet. But it’s an important one, the only planet we know of so far in the universe that is home to life: Earth.

As you orbit over the Poles, your role is to measure the “energy balance” that governs Earth’s temperature. With one eye looking down, you measure the outgoing heat escaping from the surface and atmosphere. With the other eye looking up, you measure the incoming solar radiation that heats Earth from above. Subtracting the former from the latter, you estimate the net heating of the planetary system.

To perform this key task, you use an instrument called CERES, which measures “Clouds and the Earth's Radiant Energy System.” CERES has shown us that Earth has a positive energy balance—confirming that the surface and lower atmosphere are warming up faster than Earth can cool off.

But is that heating leading to a discernible increase in Earth’s global temperature? You’re well-equipped to answer that question, too, with a custom-designed thermometer called an Advanced Technology Microwave Sounder. The device detects microwaves emitted from our atmosphere at 22 specific energies, or channels. With some assumptions and rather involved calculations, your minders at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration can take these channel readouts and convert them into temperature estimates for the atmosphere’s various layers. You not only can monitor the lower troposphere, where we live, but also the stratosphere where jetliners fly.

A decade ago, your forerunners found themselves embroiled in some controversy, when some scientists mis-analyzed their microwave sounding measurements to argue against global warming. However, by the time you were born, these complications and nagging questions had been settled, and your readings are now nicely confirmed against other temperature measurements.

Each of these records, including yours, independently demonstrates that the surface and lower atmosphere are warming. Moreover, the changes that you’ve seen suggest that the troposphere is warming while the stratosphere is cooling—precisely the “fingerprint” climate models predict from warming caused by increasing greenhouse gases, rather than natural factors like changes in solar brightness.

Just like us, you bear a responsibility to say something when you see something. And you have. Your scientific findings have issued a stark warning to us all: Climate change is real, and it is human-caused.

Your vigilance has revealed many other details of our atmosphere. Your Cross-track Infrared Sounder maps out the 3D properties of our atmosphere, including temperature, air pressure, and moisture content. That provides us with an understanding of the dynamics of the atmosphere, which not only helps us improve weather forecasting models, but also gives a more complete picture of climate phenomena such as the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a multi-year change in the tropical Pacific’s wind and ocean currents. ENSO affects seasonal weather patterns around the world, including North America. In March 2019, NOAA warned that large parts of the U.S. will see record flooding this spring as a result of both a moderate El Niño steering moisture-laden air our way and the general impacts of climate change, which has yielded a warmer atmosphere that supports more intense rainfall.

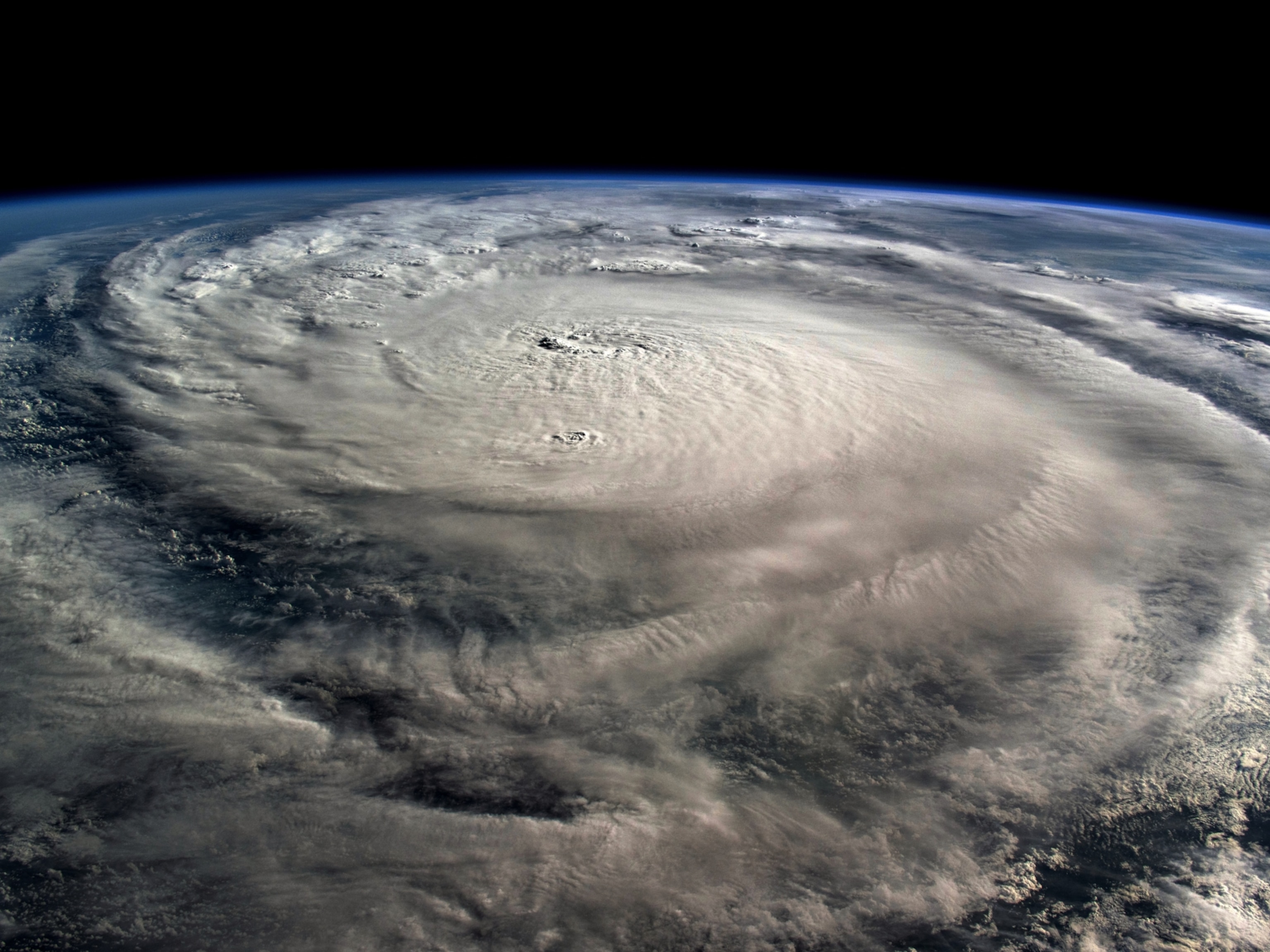

ENSO also influences Atlantic hurricanes, and climate change in turn can affect ENSO, potentially altering the frequency and intensity of hurricanes. Just how this all will settle out is a bit of a wildcard; climate models don’t yet agree. But the best available climate science indicates that the strongest hurricanes are getting stronger, and they’re making more flooding rainfall.

Fast Facts: NOAA-20

Agency: U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Launch Date: November 18, 2017

Launch Vehicle: United Launch Alliance Delta II 7920-10C

Launch Mass: 4,850 pounds (2,200 kg)

Power Source: 2,775-watt solar panel array

Orbital Altitude: 512 miles (824 km)

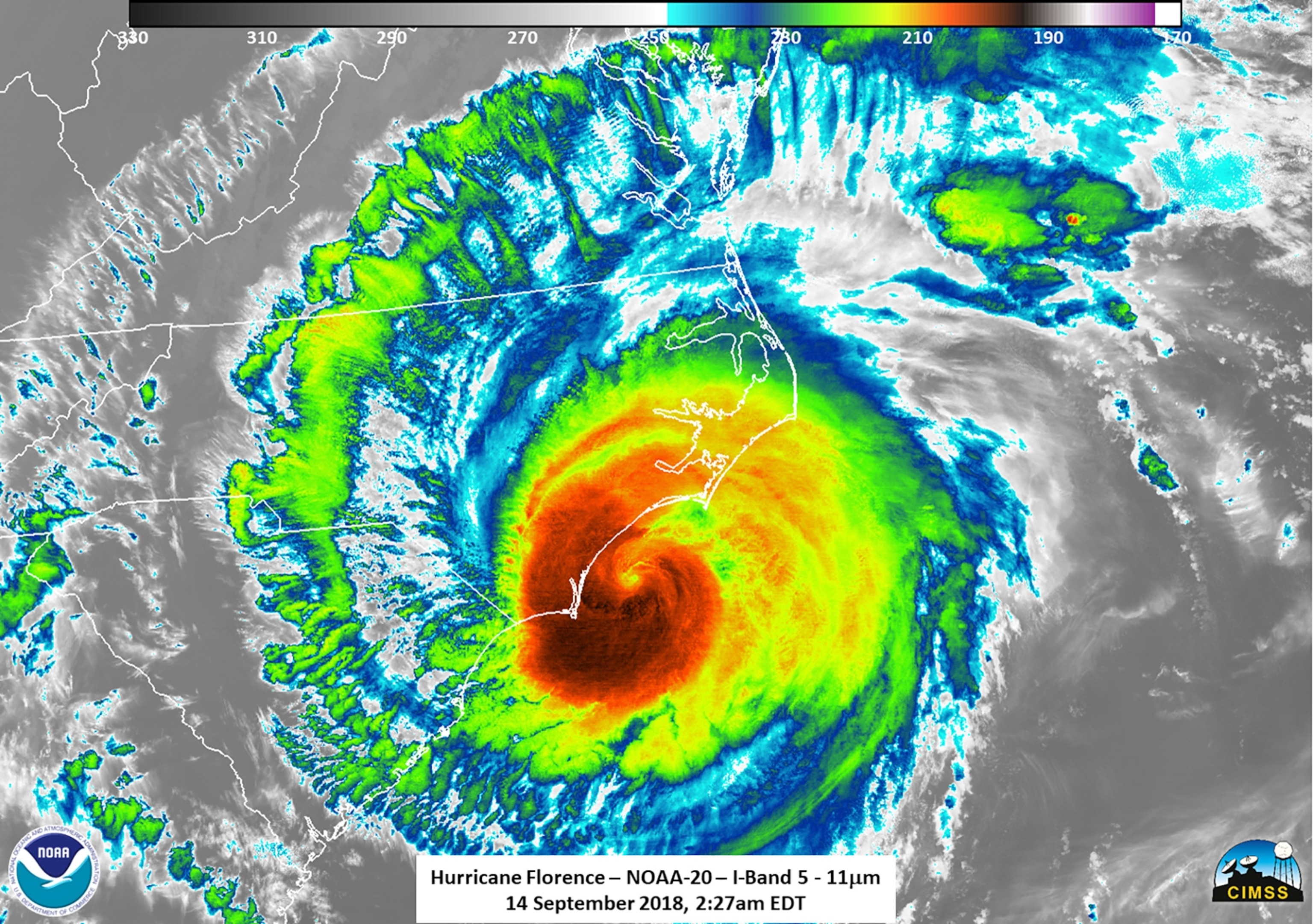

Case in point: 2018’s Hurricane Florence. Unusually warm Atlantic sea surface temperatures off the southeast U.S. coast let the storm intensify rapidly, which made its storm surge even more devastating. Those same warm waters also guaranteed extra water vapor in the atmosphere, which later contributed to inland flooding. To add insult to injury, the system stalled after it made landfall, soaking large parts of North Carolina for days on end in what’s now the second-worst flooding event in U.S. history. (The worst occurred just one year earlier, when Hurricane Harvey dropped more than a hundred billion tons of water on Houston, Texas, under similar conditions—a deluge certainly worsened by climate change.)

We know all this about Hurricane Florence in part because you, NOAA-20, helped monitor this threatening storm, along with many others. Your Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite measured the temperatures—and therefore the heights—of Florence’s cloud tops, which got higher and colder as the storm grew more powerful. In helping us monitor the increasing dangers of landfalling hurricanes, you have not only helped save lives today, but you also help us better prepare for the threat of a changing climate.

Just like us, you bear a responsibility to say something when you see something. Your scientific findings have issued a stark warning to us all: Climate change is real, and it is human-caused.

So once again, I thank you, NOAA-20. You may not be as flashy as some of your cousins, but you play one of the most important roles of all. In our exploration of the universe, including the many exoplanets orbiting distant stars that Kepler found, Earth remains the only planet we know that can provide a home to us—or any life at all, for that matter.

We must take care of that home, and that requires monitoring its health constantly. That is what you do, my friend. And I, for one, deeply appreciate it.