Purpose-driven inventors: Bringing the sea floor to the surface

Advances in technology are helping explorers fulfill their purpose: Mapping the ocean floor in tiny detail for the first time.

In the early 1950s, Marie Tharp began connecting dots to map the ocean floor, using sonar technology. Sonar detects underwater objects by timing the echo of a soundwave and was originally developed to discover icebergs and later, submarines. Marie deployed it to measure the depth of the seafloor. She painstakingly took sonar readings from ships and plotted the data dots on a canvas map. As she did so, the technology transformed the seafloor from a two-dimensional unknown, to a complex landscape of plains, seamounts, canyons, and chasms. A woman in a male dominated field, Marie’s findings were initially ridiculed and dismissed, but armed with technology and driven by purpose, she was the first to reveal the world beneath the waves.

Even so, little more than 25 percent of the ocean floor has been mapped in detail: We know more about the surface of Mars. This prompted astrophysicist and National Geographic Explorer, Ved Chirayath, to turn his use of technology designed for the enormity of space to the unexplored seas that cover two-thirds of our planet.

Imaging this vast and rich seascape is critical to understanding the geology, biology, and ecology of the largest living space on Earth—and to help in the mitigatation of the urgent threats it faces. Technology is crucial in this mission, but sonar alone cannot provide the high-resolution detail demanded by science. For this, new technologies needed to be invented.

Among the most significant and prolific technological developments of recent decades has been the innovation of semiconductors and chip-enabled devices. Today, many of the increasingly powerful and sophisticated computer processors found in almost every electronic device are built by UK-based compute platform company, Arm.

The world’s largest technology companies use Arm’s innovative and advanced compute platforms to deliver the processing power needed to execute complex activities, including artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). As the demand for power-efficient, high-performance processing grows, Arm technology is in everything from supercomputers and satellites to smartphones and the tiniest sensors. They are even at the heart of many high-tech tools being used to explore our oceans.

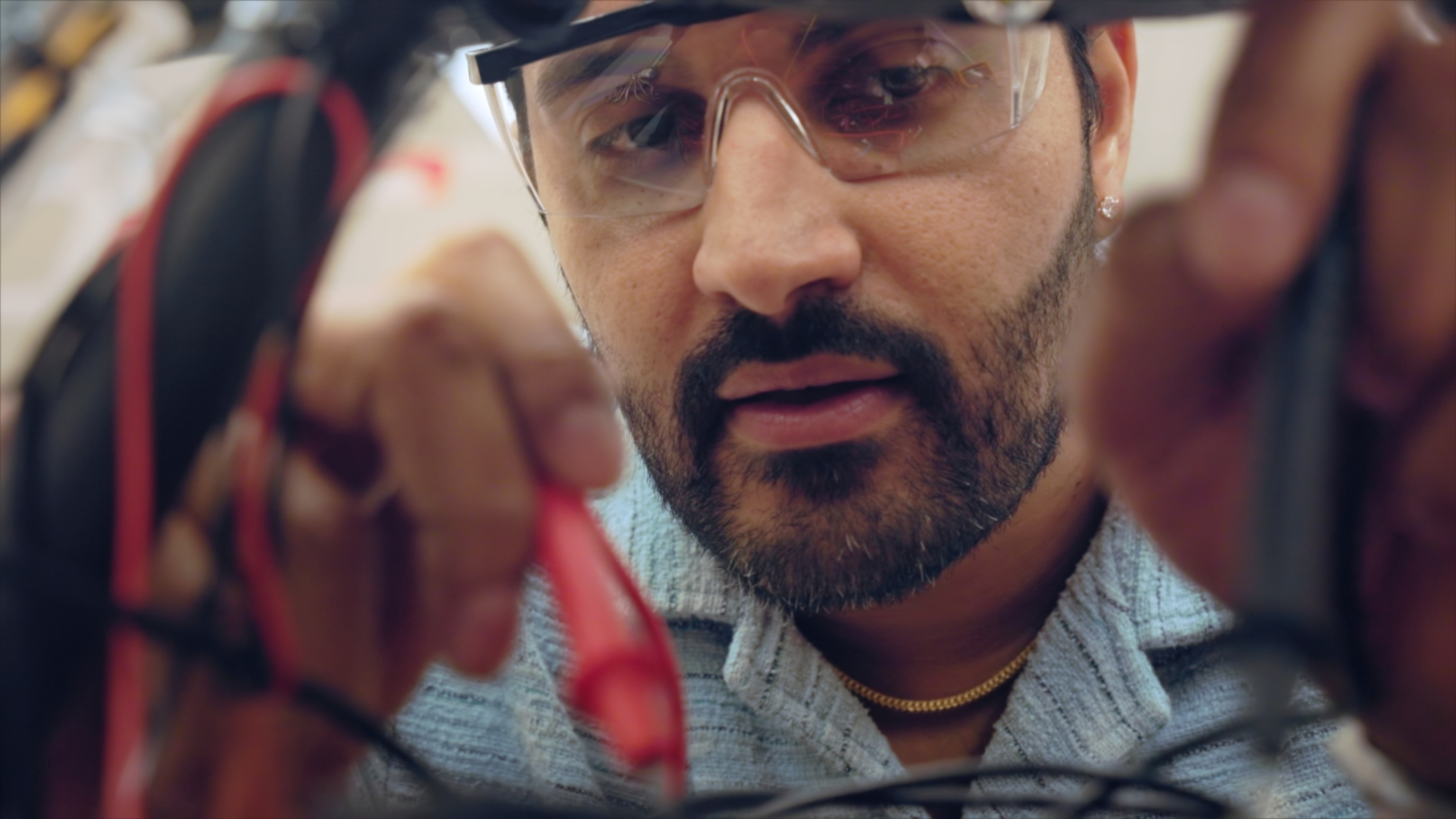

Purpose-driven inventors like Ved rely on these technologies. After 10 years’ innovating breakthrough inventions at NASA, Ved is adapting space exploration tools to map Earth’s oceans in detail. His passion for using technology to explore what cannot be seen stretches back to high school, where he modified a digital camera and a telescope to detect a planet 150 light-years away.

Today, Ved’s work is inspiring and enabling future talent as he leads a multidisciplinary team developing new remote-sensing instrumentation that can penetrate the depths of the ocean with unprecedented clarity, and creating the machine learning algorithms to process and interpret the data produced. Across three key inventions, Ved is mapping the oceans in detail.

Ved’s invention, the FluidCam, came from space exploration. Large galaxies warp starlight around them, acting as a lens that focuses the light from the galaxies behind them to allow us to see farther into space. Ved applied this principle to water. Looking at the ocean from above, it ripples with movement and sparkles with sunlight, making it difficult to see beneath the surface.

FluidCam turns these natural phenomena to its advantage. When a wave passes over an object, its curvature magnifies it for a moment, making it seem closer. When sunlight hits the water, the waves can focus the light into caustic beams that penetrate more deeply. By combining these phenomena with high-performance processing, Arm-powered FluidCam takes 3D images of the seafloor when the resolution and the light are optimum—delivering clearer images from deeper depths. FluidCam is initially mapping the world’s coral reefs by picking out sub-centimeter details down to around almost 66 feet (20 meters), so we can better understand these crucial, fragile, and threatened ecosystems.

But with the average depth of the ocean around almost 12,000 feet (3,600 meters), Ved invented a way to go even deeper- MiDAR. Light is the challenge, as the deeper you go the less sunlight there is to illuminate objects in ways that humans can see. However, fish have evolved to use far more wavelengths of light than humans and Ved applied this principle in MiDAR. Very high-power lasers emitting blue and ultraviolet light, wavelengths that transmit particularly well underwater, allow drone-mounted MiDAR instruments to image detail even deeper than fluid lensing. By attaching MiDAR imaging to a submersible, it could reach almost any depth. MiDAR is also the first technology to use light to transmit data back to base—a breakthrough that would allow MiDAR-equipped robots to map the ocean floor methodically without needing to regularly resurface.

Such detailed 3D imaging creates vast quantities of data—hundreds of terabytes for each coral reef. To analyze this data meaningfully requires huge computational power, which led Ved to develop NeMO-Net. The latest high-power processors enable AI and ML to turn raw data quickly and accurately into maps, from which scientists can draw valuable conclusions—such as the health of a coral reef. To help AI build the necessary models for interpreting this data, NeMO-Net has tapped into citizen science and the prevalence of powerful home computing by gamifying the identification of coral. Across the world, people log on to NeMO-Net to color-in coral and classify this extraordinary environment. Their results, peer reviewed and fed into supercomputers, deliver the detailed maps that science and conservationists need.

A key technology linking all of Ved’s inventions is the processor, made ubiquitous by compute companies like Arm. Central processing units (CPU) power his inventions: FluidCam uses very high-performance chips across multiple architectures, including field programmable gate arrays that accelerate certain processes of fluid lensing. Arm microprocessors run the essential circuitry that controls MiDAR, helping capture and process data using efficient and small chips, doing computations (that previously required a supercomputer) on a device carried by a small drone.

And as microprocessors evolve, becoming more power-efficient and more intelligent, with additional AI architecture features, they will become essential to Ved’s next project: Full ocean-sensing from space, by harnessing physics beyond light, such as gravity or fundamental particles. It’s a future technology that could be crucial for not only mapping our oceans, but also for exploring the oceans of other planets, such as Europa—places where scientists believe we are most likely to find extraterrestrial life. Like Marie Tharp, Ved faces skepticism, but believes he’s on a mission that’s worth pursuing. With so much still to explore, Ved’s work is driven by purpose and enabled by technology that runs on Arm.