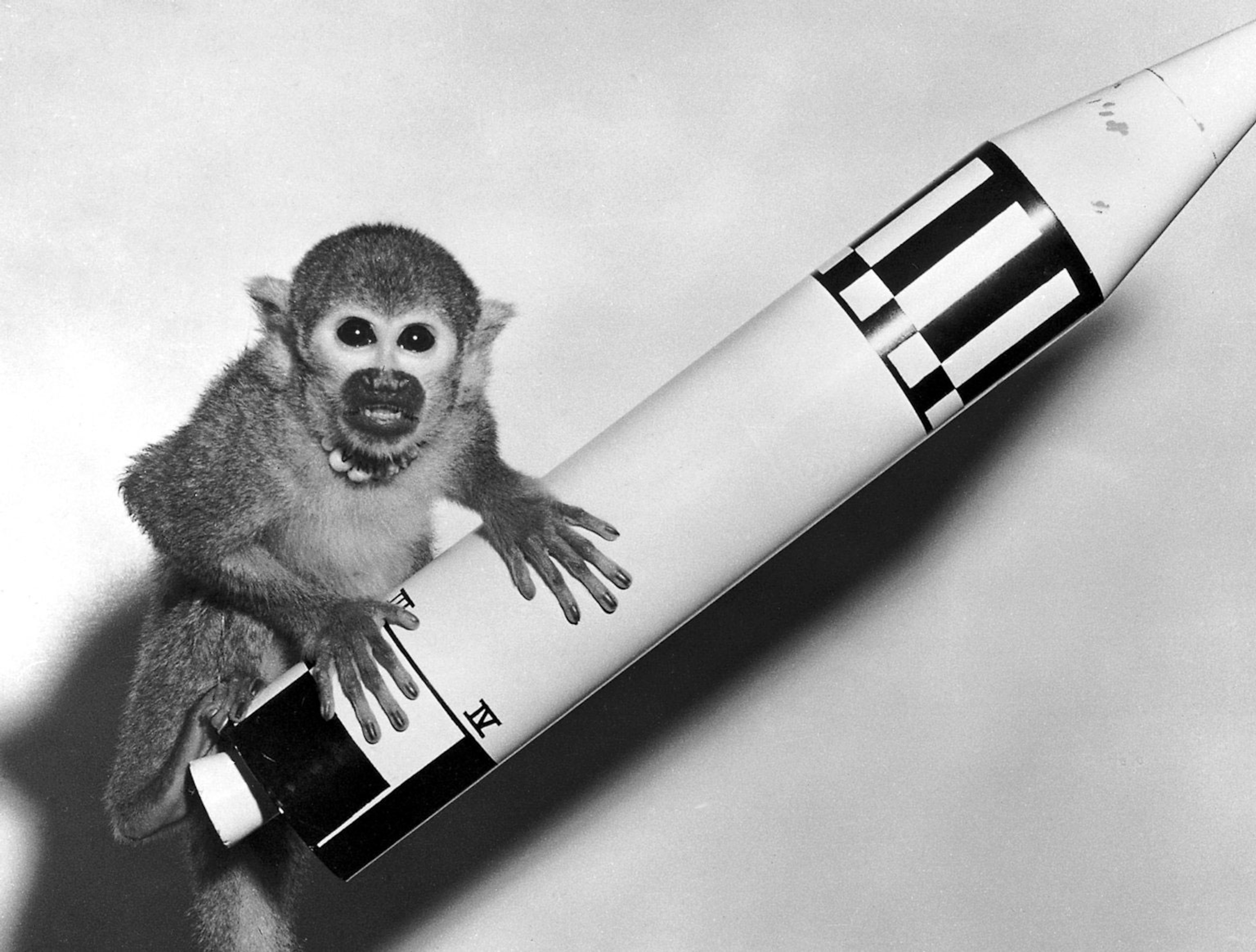

Before Bezos and Branson, there were Baker and Able.

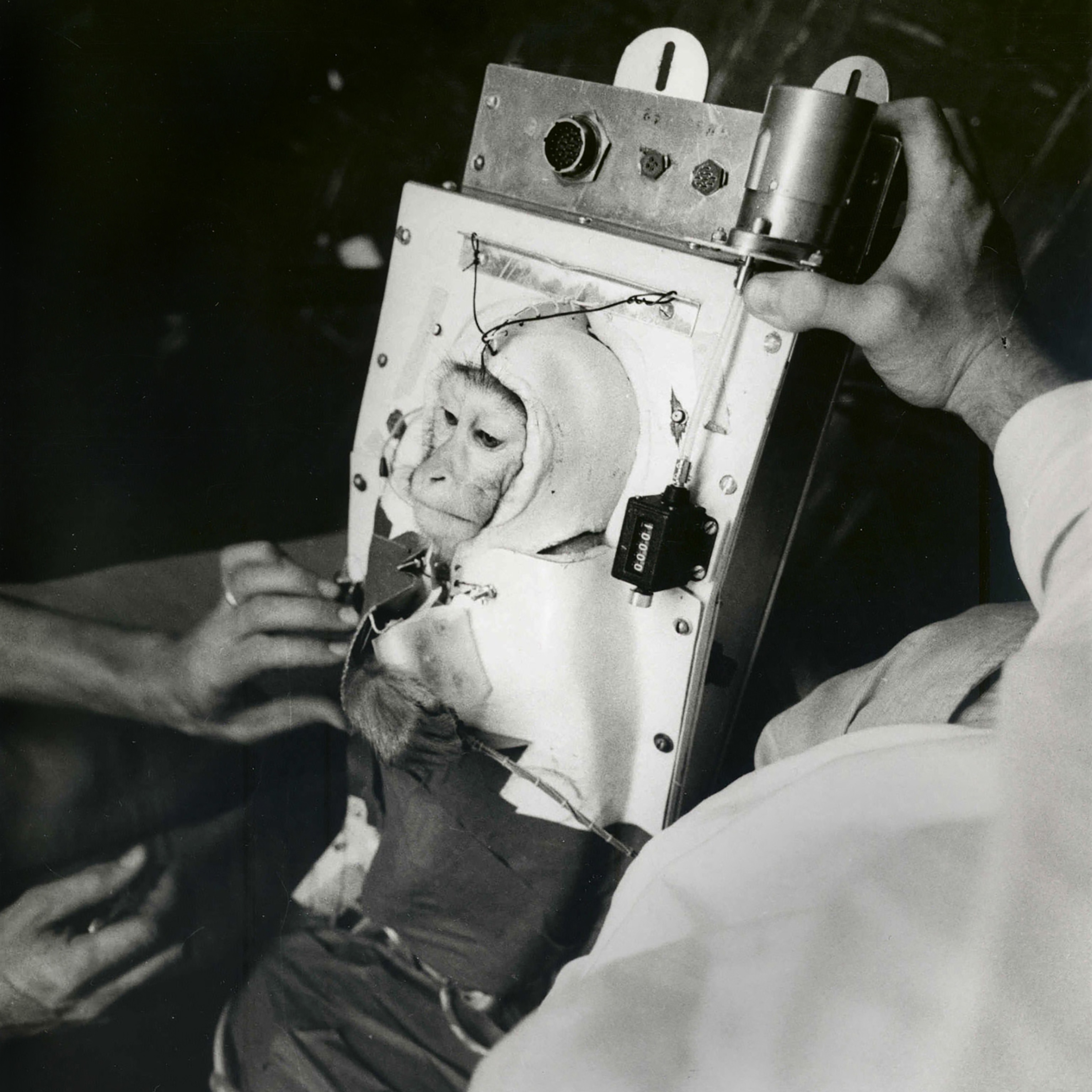

In the early morning hours of May 28, 1959, a Jupiter missile launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, sending Baker and Able—two small monkeys—hurtling across the sky like a shooting star. Over the next 16 minutes, Baker, an 11-ounce squirrel monkey from Peru, and Able, a rhesus monkey born in Independence, Kansas, flew 1,700 miles and reached an altitude of 360 miles above Earth’s surface, higher than the Hubble Space Telescope orbits today.

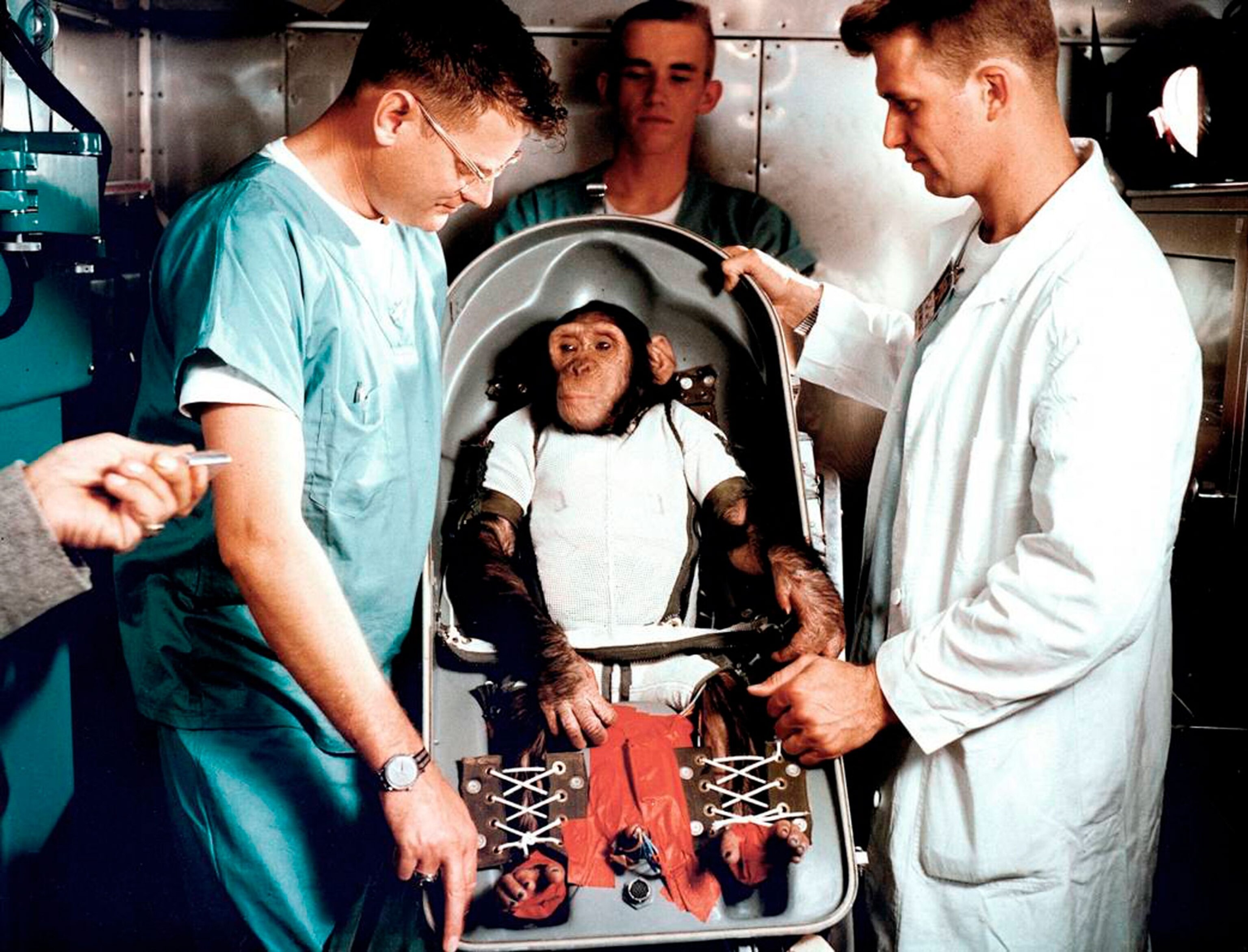

After several minutes of weightlessness, the monkeys fell back to Earth in the missile’s nose cone, with Baker snug in a canister not much bigger than a large Thermos. The pair experienced forces 38 times stronger than Earth’s gravity during the descent. When they splashed down in the waters off Florida, Baker and Able made history. For more than a decade, the United States had been trying to send monkeys into space and return them safely, but all had either died in flight or within two hours of landing. Baker and Able, however, came back alive and well—the first primates to survive a trip to space.

Able died in a medical procedure days later, but Baker lived until 1984, when she was buried at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. People leave bananas at her grave to this day.

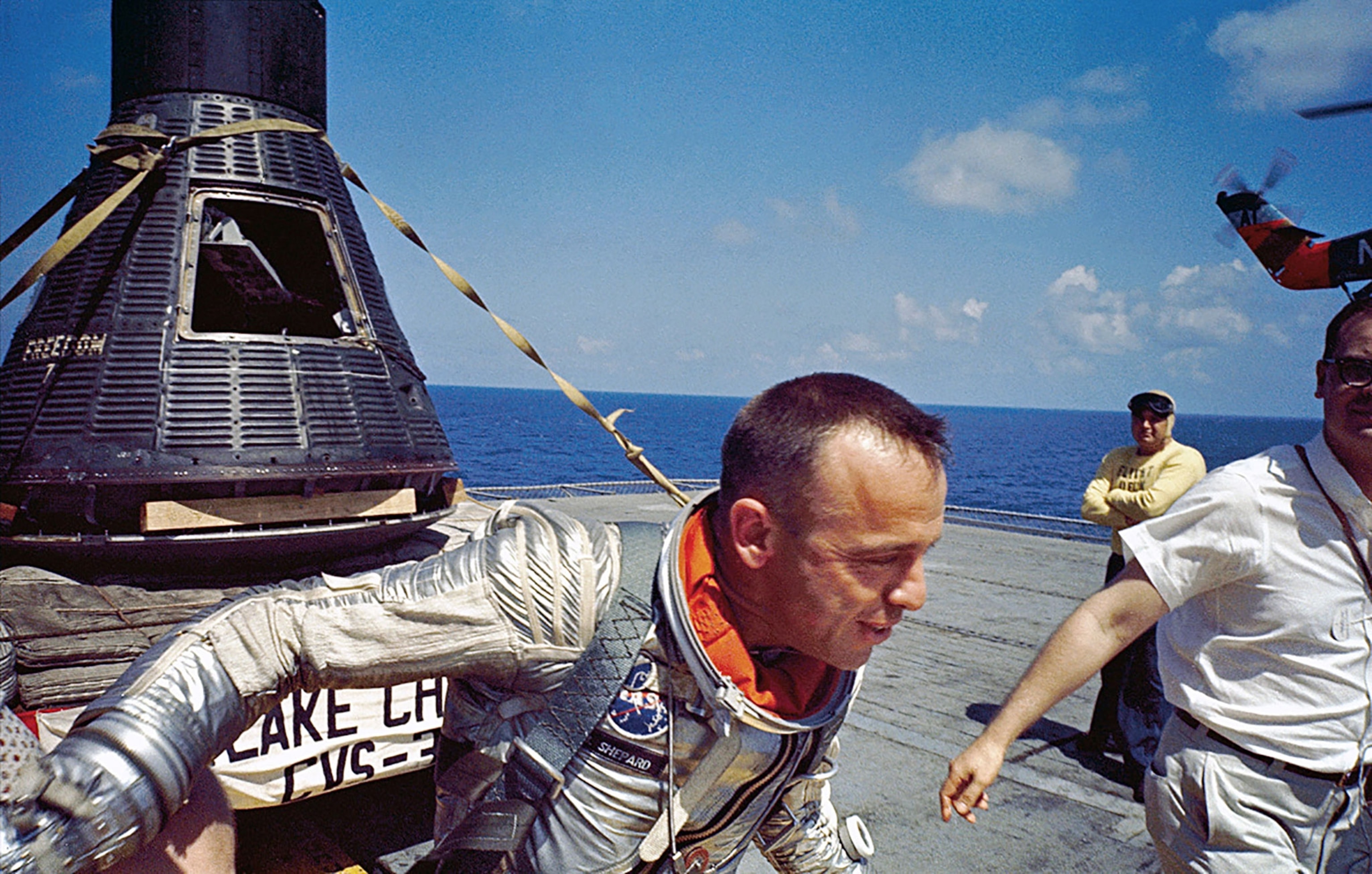

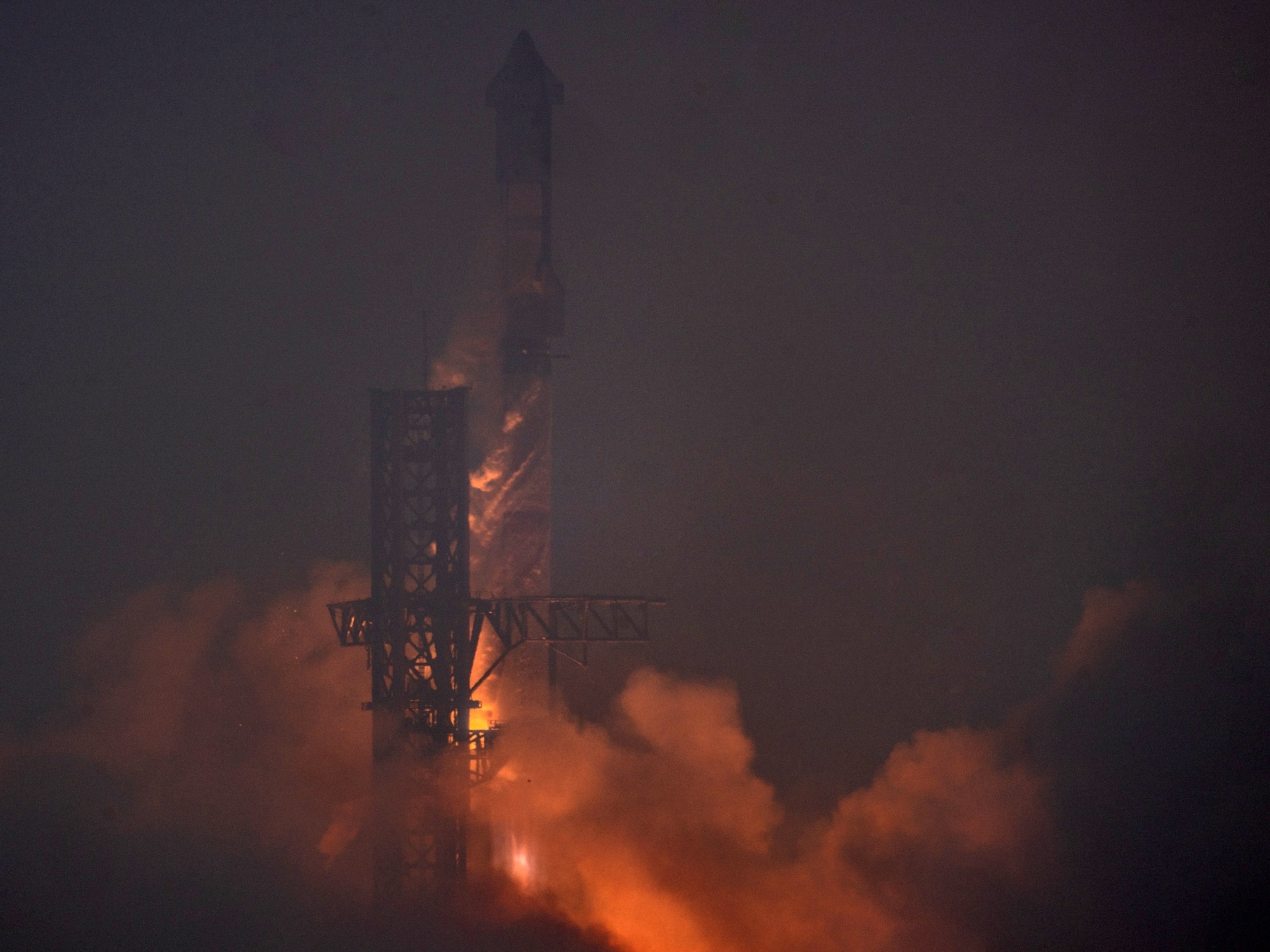

Now, nearly 600 people have ventured more than 50 miles above Earth’s surface—the U.S. boundary for space—and human spaceflight is entering a new phase. Flights beyond Earth are becoming cheaper and more frequent, and private enterprises are aiming to send more people to space than ever before.

What does the future hold for human journeys beyond Earth’s atmosphere? How often will future generations fly to orbit and beyond? How far will explorers travel?

To get a sense of how space exploration got here, and where it may be going, National Geographic looked back through more than six decades’ worth of spaceflight images, highlighting historic moments in humans’ forays into the inky void.