Pregnancy transforms the brain—and some changes last forever

For the first time, scientists have observed the brain throughout the pregnancy timeline, from pre-conception to postpartum.

Sex hormones, like estrogen and testosterone, are powerful players in the brain, affecting mood, memory, and more. Some of the most dramatic hormonal changes that humans experience happen during pregnancy, and yet those nine months have been a black box for human neuroscience until now.

A new study published this week in Nature Neuroscience provides the most extensive glimpse inside that black box yet. Researchers scanned the brain of one woman 26 times over the entire course of her pregnancy—before, during and after.

“Not only is this critical for our understanding of this uncharted period of time in a woman's life,” says Emily Jacobs, a neuroscientist at University of California, Santa Barbara and an author on the study. “There also may be nuggets of gold—like knowledge that is lying just under the surface because we never bothered to look at this.”

Fascinated by the impact of sex hormones on the brain, Jacobs and her team began a project called 28 and me a few years ago to document changes in women’s brains throughout their menstrual cycles. Liz Chrastil, a neuroscientist at University of California, Irvine, and friend of Jacobs’ lab, approached the team with an idea to expand their research to another period of dramatic hormonal change: her pregnancy. Studying the brain during pregnancy can be difficult, or even impossible, because of the extensive safety protocols involved.

“Liz came to us and said ‘well we could also do this with me. I'm planning on having a baby,’” recalls Laura Pritschet, a neuroscientist at University of Pennsylvania and lead author of the study. Chrastil was willing to be scanned repeatedly before, during, and after her pregnancy, which would allow the team to elucidate a detailed timeline of changes in brain structure and hormone levels throughout the process. “That gave us this ability to ask this new question that really has never been studied before.”

(How does the menstrual cycle reshape the brain?)

Brain ch-ch-ch-changes

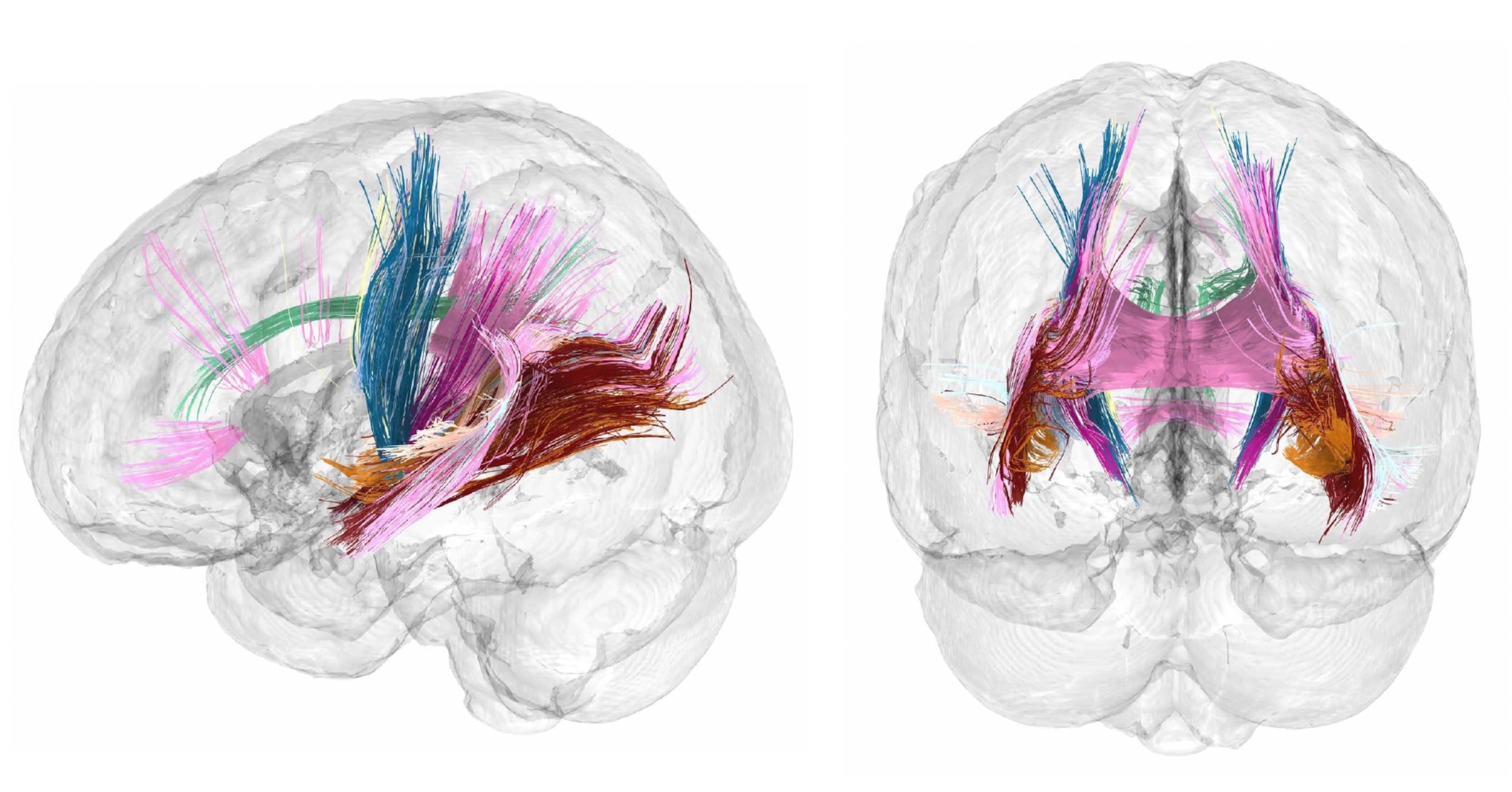

Previous brain imaging studies from before and after pregnancy have shown that pregnancy shrinks parts of the brain, specifically its gray matter. These outer layers of the brain are responsible for most of the cognition, sensation, learning and other great things the brain does.

Shrinking gray matter may sound scary, but it happens to all of us throughout development to fine-tune our neural processing and make our brains more efficient. Though the term “mommy brain” is often used to refer to the brain fog and forgetfulness some people report feeling during pregnancy, the brain changes are likely adaptive. “You may be forgetting where your keys are, but you are way more wired to what is happening to your offspring,” says Pritschet. She is particularly interested in changes within brain regions that help with social cognition by allowing us to take on others’ perspectives.

The scale and pattern of brain changes during pregnancy are similar to what other researchers have seen in adolescent brains during puberty, also driven by hormones. Other researchers have been able to detect whether someone had been pregnant based only on neuroimaging data from decades later. So despite the common adage that our brains stop developing in our mid-20s, hormones seem to drive big, long-lasting changes throughout adulthood.

“I think these are like permanent etchings in the brain and people carry the trace of this for a long time,” says Jacobs.

From studying Chrastil’s brain, Pritschet and her co-authors confirmed that gray matter decreased by over four percent over the course of pregnancy and that decrease persisted throughout the end of the study two years postpartum. Unlike previous studies, the team was able to show that gray matter decreases steadily throughout pregnancy starting in the first weeks of pregnancy, stabilizing around the time of birth and persisting years after birth. The changes correlated with rising concentrations of two sex hormones, estradiol and progesterone. And it wasn’t just one area or network—80 percent of brain regions shrunk. While certain areas and networks changed faster than others, the team doesn’t yet know what the implications are.

While the team was expecting to find gray matter shrinkage, they were surprised by the changes they saw in the brain’s white matter, the bundles of nerve fibers that run through the brain and help neurons communicate with each other. The white matter grew stronger, peaking in the second trimester and then decreasing almost to normal by the time of birth. Though their data doesn’t explain what stronger white matter would mean for a new parent, similar changes in adolescents correlate with better cognitive abilities.

“Such transient findings only surface in a study like this that involves many sessions throughout pregnancy,” says Elseline Hoekzema, a neuroscientist at Amsterdam University Medical Center in the Netherlands who was not involved in the study.

Though this study only included one participant, the team has already started scanning other soon-to-be mothers and continues to receive an overwhelming number of people interested in participating.

“My goal with this one-subject study is just to sort of shout from the rooftops ‘we can do this! It's really important,’” says Pritschet.

Out of the lab and into the clinic

“Undoubtedly, this and other studies focused on characterizing brain changes in pregnant women are necessary to better understand peripartum mental disorders as well as subclinical symptoms that can appear during this period,” says Susana Carmona, a neuroscientist at the Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Gregorio Marañon in Madrid, Spain, who was not involved in the study.

Depression during and after pregnancy affects 10 to 20 percent of people who give birth and many more likely suffer from similar symptoms without being diagnosed. With so few studies on pregnant human brains, a reliable way of detecting perinatal depression is still out of reach.

The team hopes that this study and further research may shed some light on typical pace of gray and white matter changes throughout pregnancy. After establishing the typical pattern, researchers could identify abnormalities that might be signs of perinatal depression.

“Who knows what sort of clinical utility will emerge from this but first we have to value this as a question worth studying and for too long science has simply ignored it,” says Jacobs.

Beyond the pregnant brain

Given that over 85 percent of women experience pregnancy in their lifetime in the U.S., it’s surprising that researchers know so little about its effect on the brain.

Women’s health issues are notoriously understudied, and pregnancy falls under that research umbrella. Researchers have only been required to include women in NIH-sponsored clinical trials since 1993, and many clinical trials still exclude pregnant women. Less than 0.5 percent of brain imaging articles published over the last 25 years consider health factors specific to women.

(Scientists are finally studying women’s bodies. What are they learning?)

Sometimes these exclusions come out of an abundance of caution. Jacobs and her team used a type of brain scan called magnetic resonance imaging or MRI, which is only unsafe for participants with metal in or on their bodies. Despite there being no proven risks for pregnant people, they are often excluded from MRI studies for fear that risks may surface in the future

“I think maybe safety is used as this blanket excuse but it's really that women's bodies have been ignored throughout the history of the biomedical sciences,” says Jacobs.

Jacobs is one of many neuroscientists who believe MRIs are completely safe for pregnant people. She encourages researchers to balance caution with the potential positive impact of research when considering whether to develop studies on pregnant participants.

“Before this was published, we shared our protocol, and it has actually helped some people be able to go to their imaging center and say ‘let's scan pregnant people. This is okay,’” says Pritschet. “So it's really just trying to jump start this growth of the maternal brain field and bring it into scanning during pregnancy.”

For researchers who would rather not conduct imaging studies themselves, the team has made their data openly available for anyone to download. They hope others will use their data to test out different analysis techniques even beyond the pregnant brain.

Research consortiums like the Ann S. Bowers Women's Brain Health Initiative, directed by Jacobs, are facilitating collaborative efforts to expand scientific understanding beyond the cisgender male body. Encouraging research on the brain effects of pregnancy, menopause, hormone therapy, and other major changes in hormones will be an integral part of representing women and gender minorities in science.

“It's not just women who are suffering from our lack of studying these sorts of phenomena,” says Jacobs. “It's everybody.”