Icy Moon May Have the Right Stuff to Fuel Life

A recent flyby suggests that if there’s life on Saturn’s moon Enceladus, there’s probably plenty of food for it to consume.

Something hot seems to be churning deep inside an icy moon, and NASA scientists think that it might be enough energy to fuel any hypothetical extraterrestrial life.

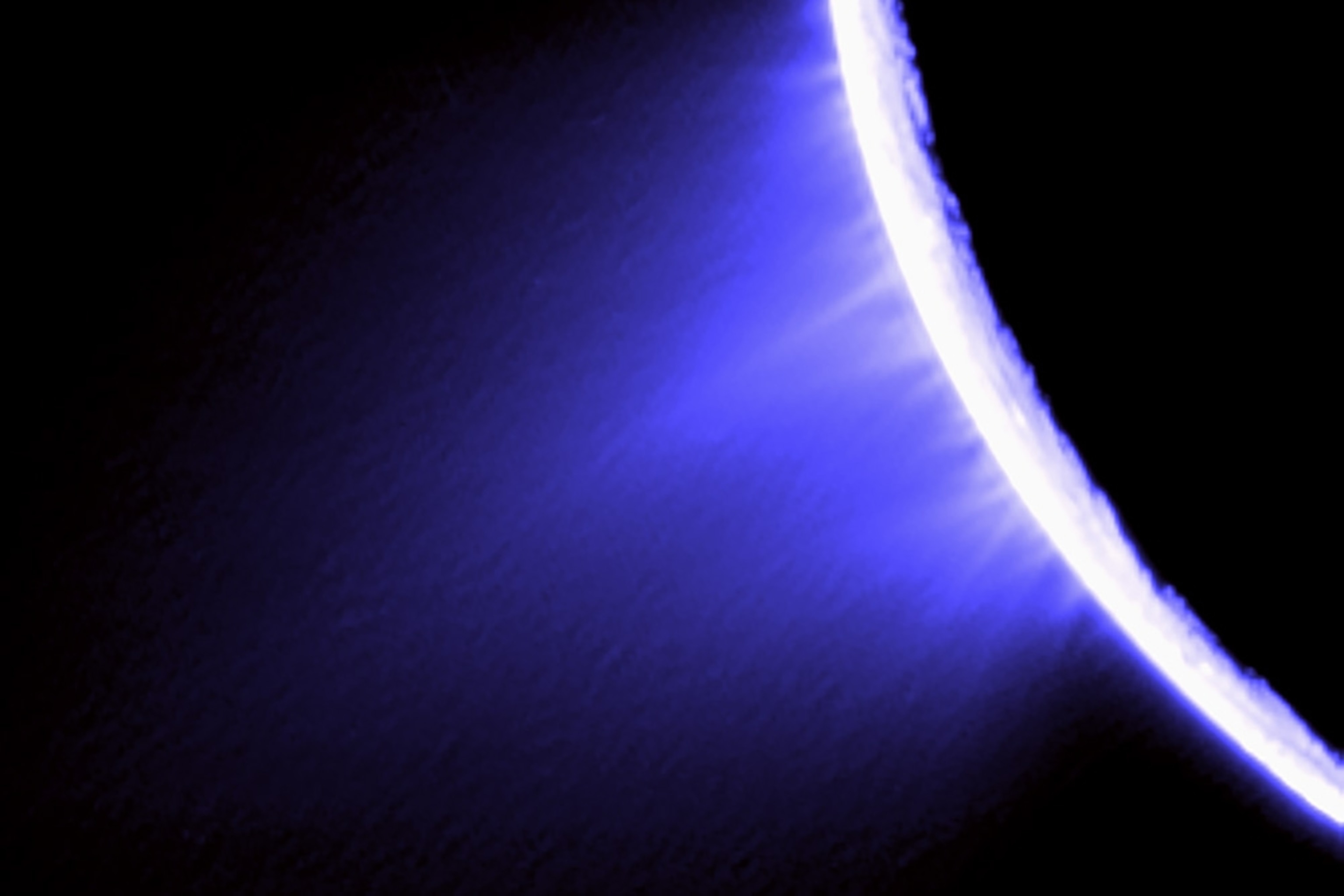

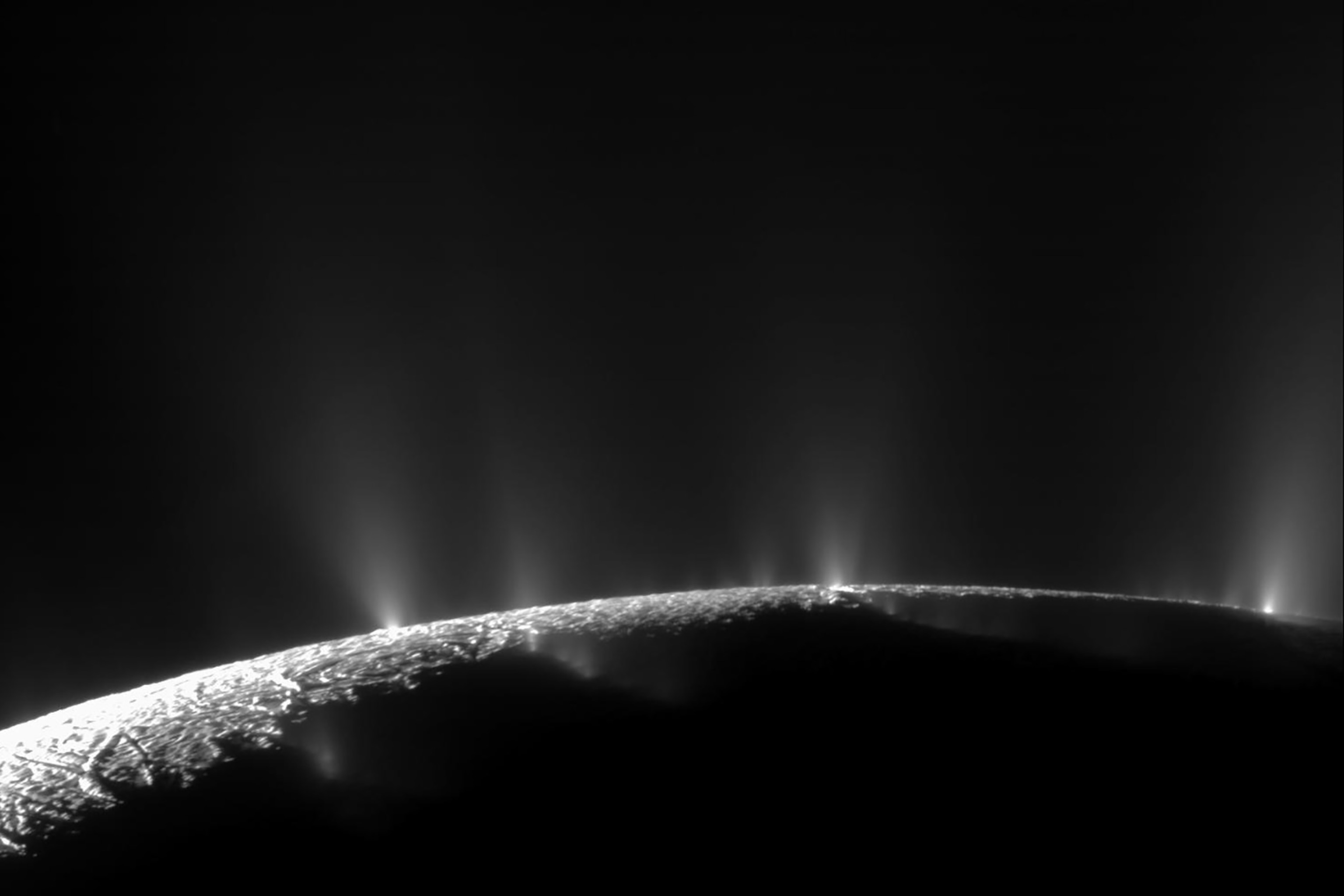

The Cassini spacecraft had previously flown through the watery plumes coming out of Saturn’s moon Enceladus, “tasting” their contents and discovering that they are laced with salts, simple organic molecules, and ammonia—key building blocks for life.

At a Thursday press conference, scientists led by Southwest Research Institute scientist Hunter Waite announced that during an October 2015 flyby, the spacecraft’s instruments also detected molecular hydrogen within the moon’s plumes.

The gas, most likely produced as rocks and scalding water intermingled on the world’s seafloor, provides additional evidence that Enceladus currently has hydrothermal vents—and that they’re vigorous enough to power life.

“It’s a very exciting and compelling result that helps build the case for Enceladus being a potentially habitable ‘ocean world,’” says astrobiologist and National Geographic Explorer Kevin Hand of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Savor the Flavor

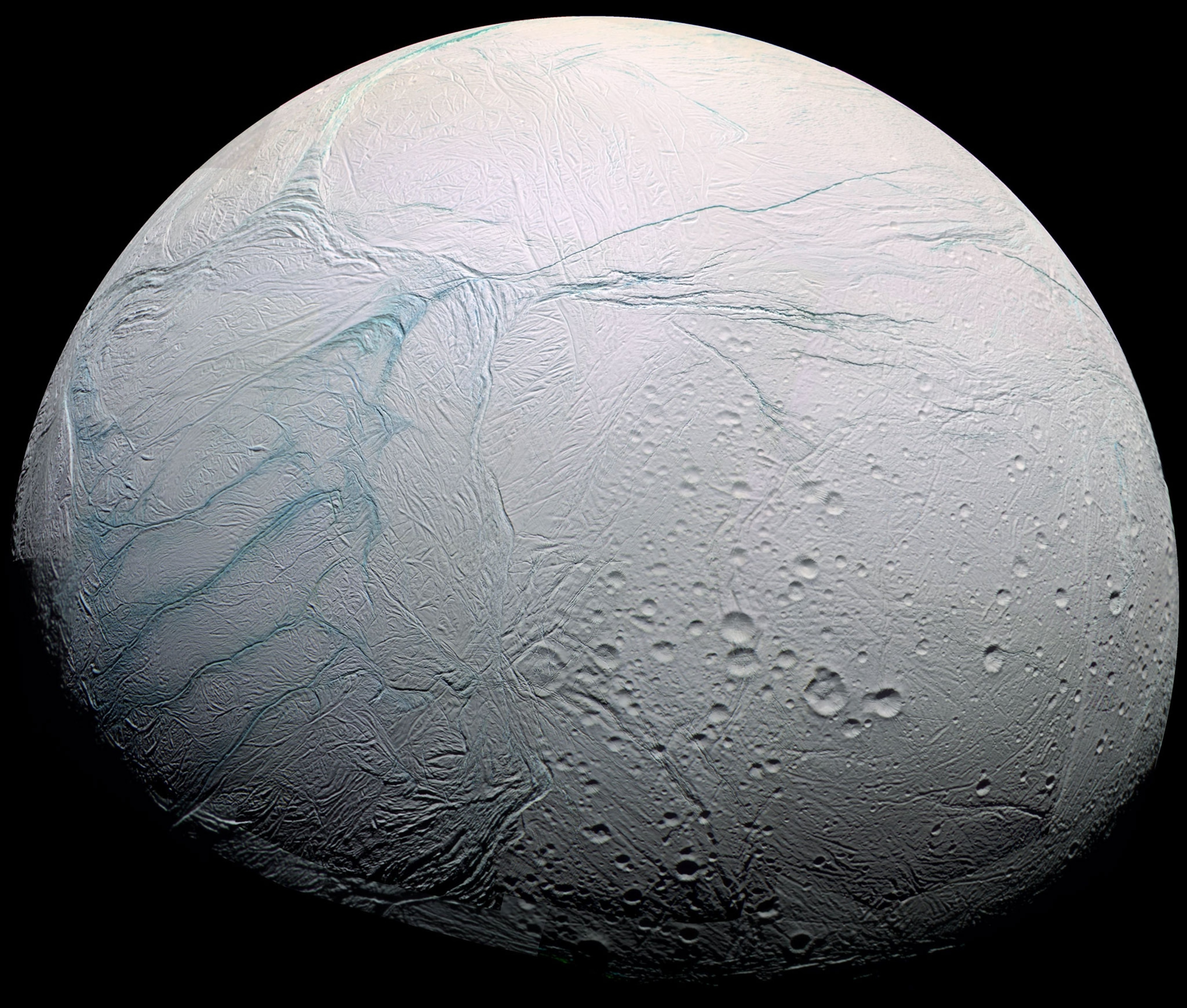

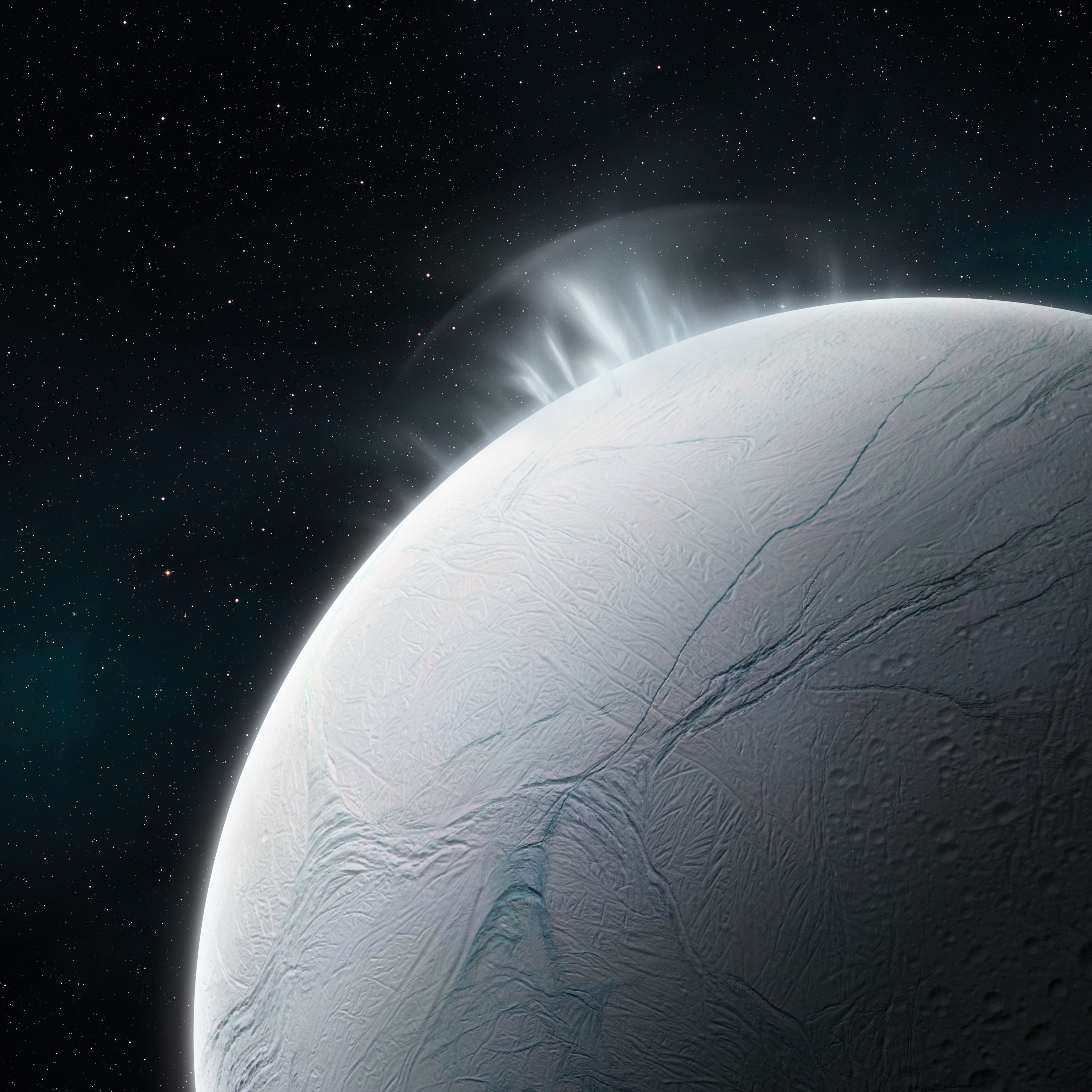

Enceladus’s orbital wobbles show that the moon’s core and icy shell slightly slip past each other, a scenario best explained by a lubricating global ocean of liquid water at least 16 miles thick. And ever since Cassini first detected the moon’s plumes in 2005, evidence increasingly shows that the waters underneath could be habitable.

“We don’t know of any other ocean world better than this one, not including the Earth,” says Carolyn Porco, the imaging team leader for Cassini. “The extra bonus is that it’s trivial to sample its ocean. It’s expressing itself into space!”

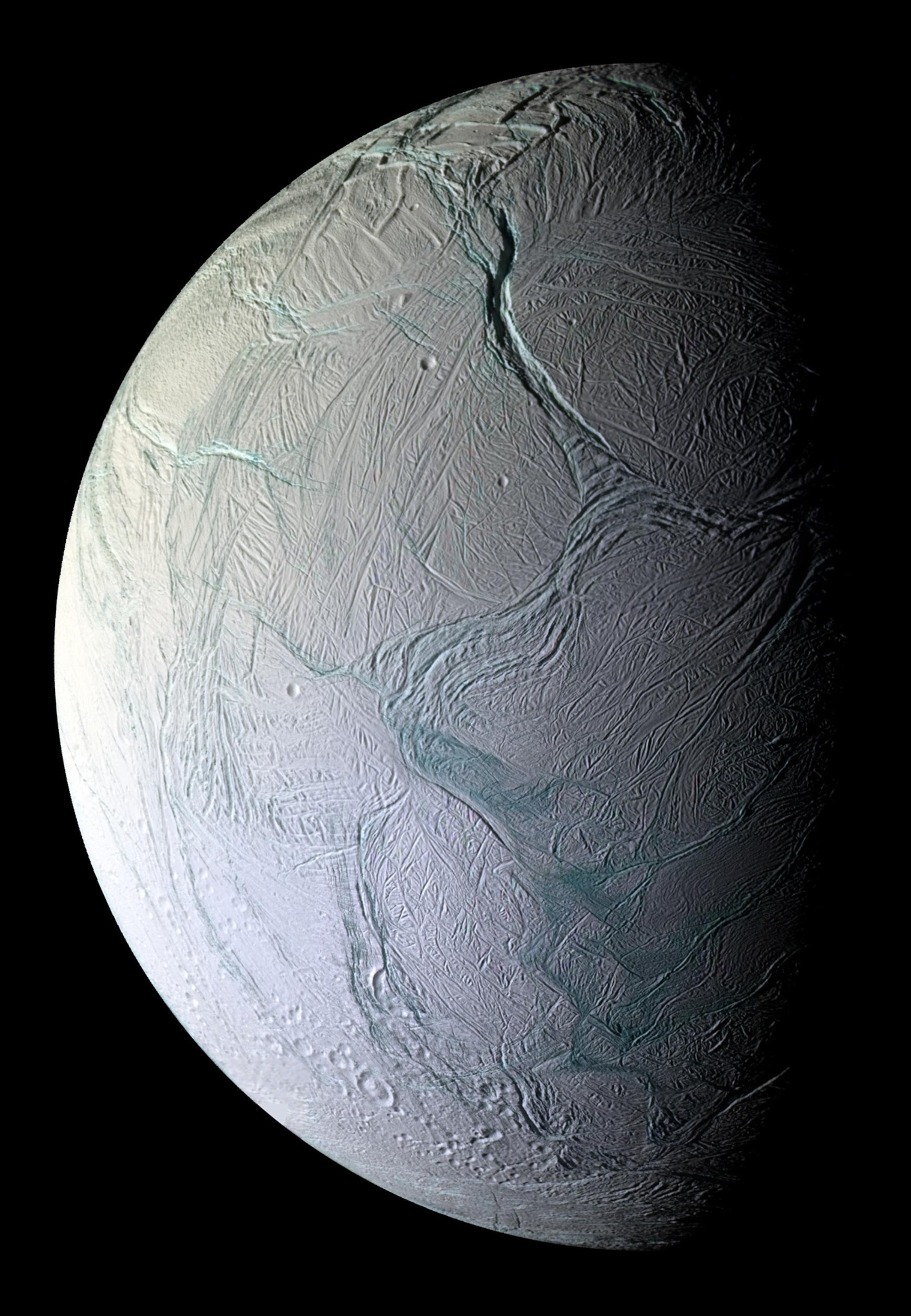

As Cassini made its deepest dive into the plumes on October 28, 2015, the craft flew within 31 miles of Enceladus at a relative speed of more than 19,000 miles an hour.

Earlier flybys had revealed that if water molecules from the plume hit the interior walls of Cassini’s instruments, the collisions could create hydrogen molecules, making it very difficult to tell whether the plumes themselves contained hydrogen.

After years of tweaks, the researchers hunting for hydrogen eventually put Cassini’s mass spectrometer—essentially, the spacecraft’s tongue—in a mode that prevented incoming particles from touching its interior walls. However, this change made Cassini’s chemical sense of “taste” hundreds of times less sensitive.

“We were afraid we wouldn’t even see a signal,” says Waite. But during the epic descent, the team saw hydrogen gas levels increase to more than a hundred times the background levels.

Once they confirmed that Enceladus was belching hydrogen, Waite and his team then determined that this gas hadn’t been locked away during the moon’s formation: Because Enceladus’s gravity is weak and hydrogen gas is so light, older stuff should have drifted away long ago.

Instead, the scientists argue in the latest edition of Science that the hydrogen must have been freshly made, most likely by activity around hydrothermal vents.

High-Flying Finale

The team’s geochemical models show that microbes could consume carbon dioxide and hydrogen from the seafloor vents, producing methane as a waste product. Other microbes could hypothetically eat this methane in turn, further fueling an Enceladan ecosystem.

But just because this process is possible on Enceladus doesn’t mean that there’s any life there using it.

“The take-home story from the large quantity of hydrogen is that the chemical energy for life is there for the taking,” says Hand. “Whether or not life occurred is another question.”

What’s more, “it’s not necessarily the amount of energy that’s available, but it’s also important to think about the rate of supply,” says Harvard geobiologist and National Geographic Emerging Explorer Jeffrey Marlow, who studies Earth’s hydrothermal vents. “Is that rate of energy enough to sustain life?”

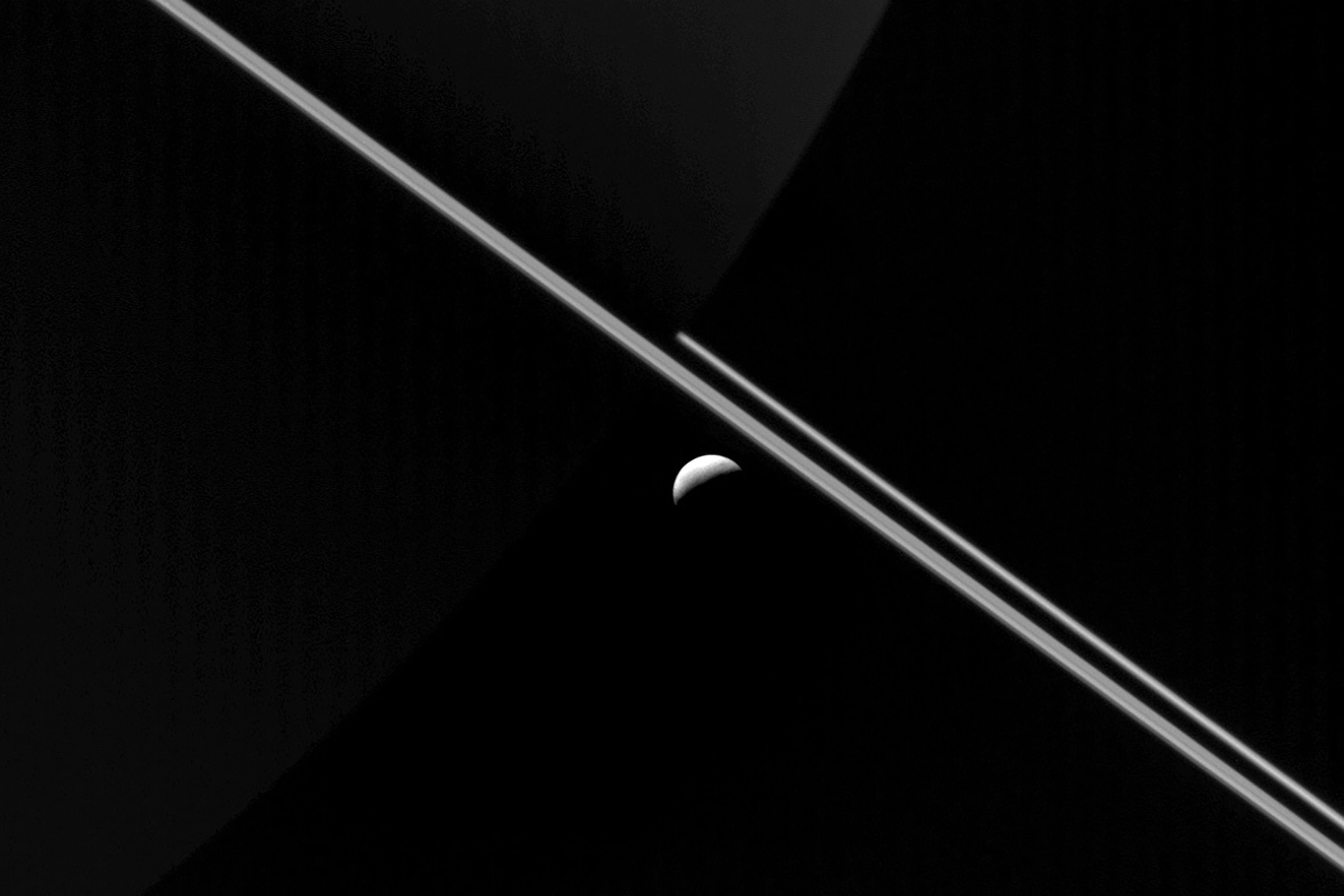

We’ll have to wait years to answer these questions. Cassini’s instruments aren’t sensitive enough to test for life, and after 13 awe-inspiring years exploring Saturn, the probe is almost out of fuel, leaving its days numbered.

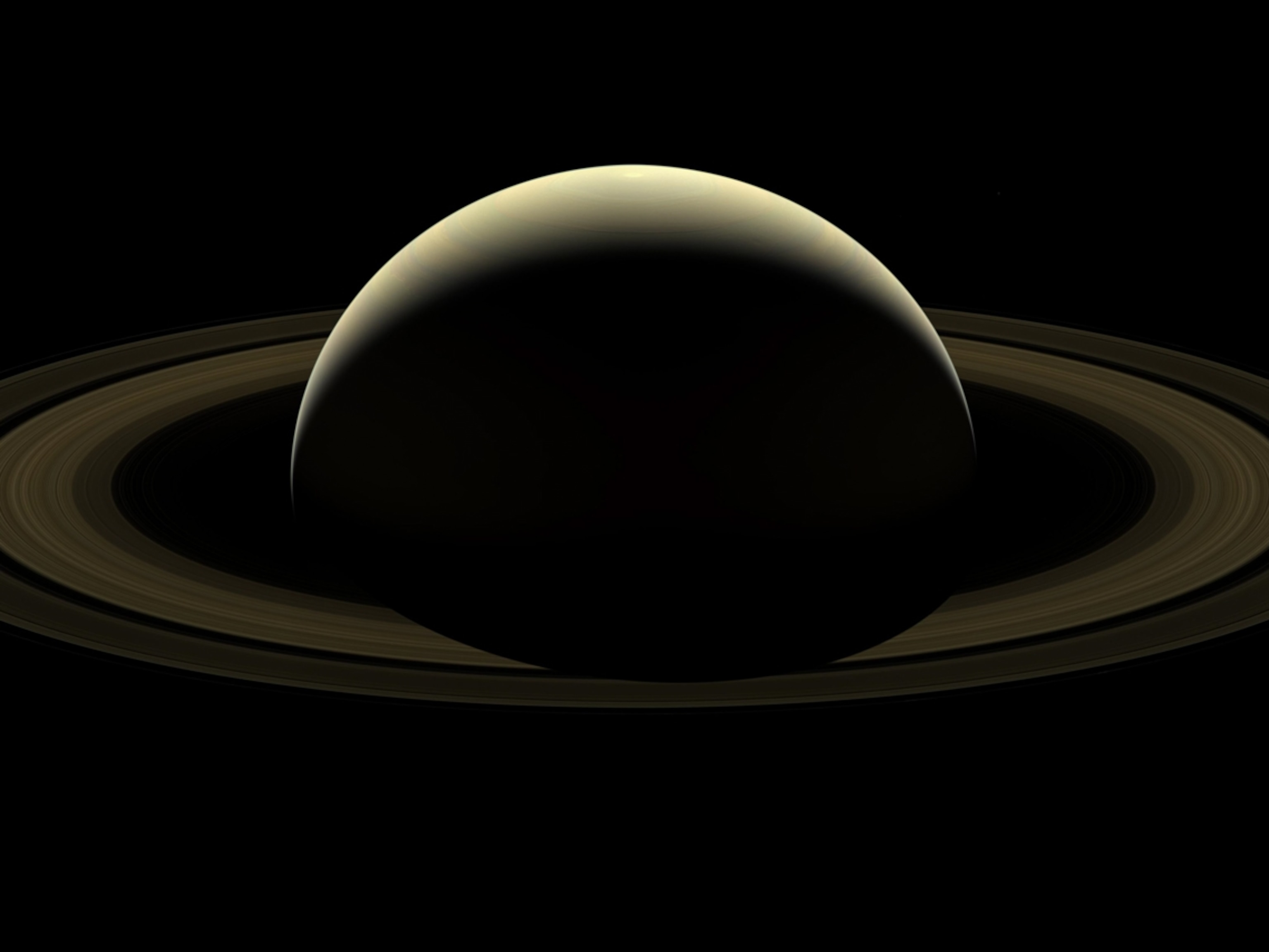

NASA is giving the spacecraft a dramatic “grand finale”—a series of 22 orbits between Saturn and its innermost rings that will end on September 15 with Cassini’s final plunge into Saturn itself.

“I look it as a major juncture in our exploration of the solar system [and] a major part of our portfolio, of humanity’s space program,” says Porco, who has been with the Cassini mission since 1990. “I look at it with tremendous pride.”

A Plume Opportunity

Even after Cassini says goodbye, though, NASA’s days of tasting plumes may not be over.

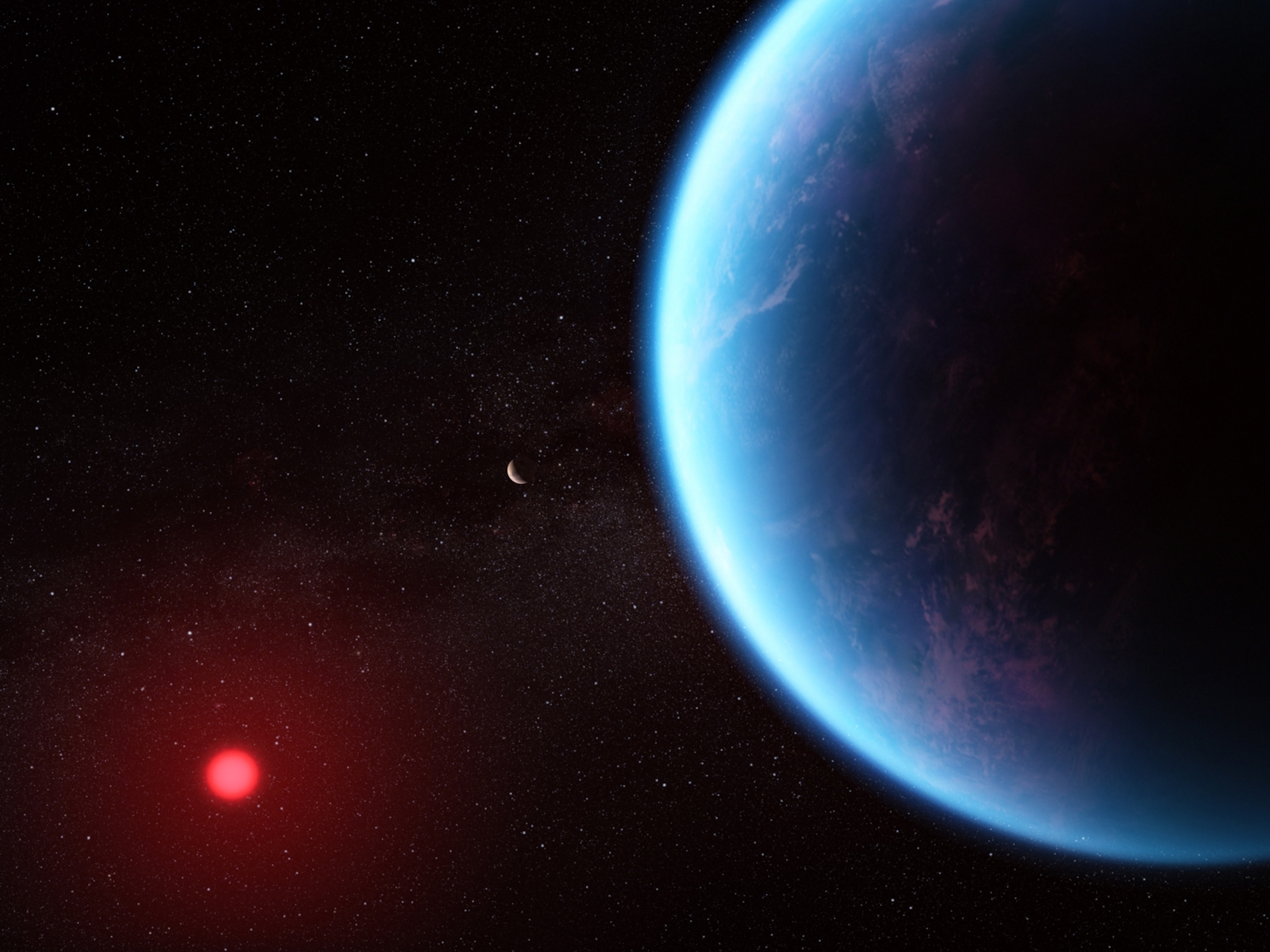

During the Thursday press conference, NASA also announced that the Hubble Space Telescope has spotted further evidence of water plumes erupting from Europa, Jupiter’s fourth-largest moon.

Like Enceladus, Europa also has a global ocean hidden underneath its icy shell, and it contains twice as much water as Earth’s oceans. Since December 2012, Hubble has seen clues that some of the moon’s waters are erupting into space.

Now, Hubble’s latest observations, taken in 2016, seem to show towering plumes erupting from almost exactly the same region where Hubble saw possible hundred-mile-high plumes in 2014.

“The best explanation is that Europa has a plume that is sporadically erupting in this region,” says Hand, who worked on the new observations, which will appear in an upcoming edition of The Astrophysical Journal. In that case, he adds, “we might be able to find signs of life captured within that erupted material.”

For instance, the moon’s plumes could provide the Europa Clipper—a NASA spacecraft scheduled to launch sometime in the 2020s—with easily accessible samples of the moon’s oceans.

“This does suggest we can access subsurface composition information at Europa … in a similar fashion to what we have done at Enceladus,” Waite adds in an email.