Could 'The Last of Us' or 'Jurassic Park' really happen? We asked scientists about sci-fi movies.

Science fiction often exaggerates or distorts science for dramatic effect—but many movies and TV shows have a nugget of realism at their core.

Science fiction has exploded in popularity over the past few decades, with Marvel movies topping box office earnings lists and long-running franchises like Star Wars and Star Trek undergoing a revival. But it isn’t just the entertainment-seeking public that loves science fiction: So do scientists, many of whom were inspired to get into their fields because of science fiction they watched as kids.

And while the science in the shows and movies scientists love is often exaggerated or outright invented, many contain a nugget of realism at their core, or a message about the role of science in society that resonates with researchers well into adulthood.

“In many of these movies, there is one overarching thing that is real,” says Marshall Shepherd, a meteorologist and climate scientist who directs the University of Georgia’s Atmospheric Sciences Program.

Here, experts weigh in on the real science behind popular movies and television shows.

Apocalyptic natural disasters

Shepherd points to a movie he enjoyed despite its scientific flaws: The Day After Tomorrow, a 2004 sci-fi disaster film in which the North Atlantic ocean’s circulation system collapses, plunging the world into a new ice age. The impacts—a giant tsunami wave engulfing New York city; tornadoes in Los Angeles; temperatures dropping so fast characters literally run away from the approaching ice—are “extremely exaggerated,” Marshall says.

But the idea that this very real oceanic conveyor belt transporting heat around the North Atlantic could shut down, amplifying extreme weather and pushing Earth’s climate past a tipping point, is real. Some scientists fear that human-caused climate change will trigger such a collapse this century.

(Learn more about this potential ocean slowdown.)

Dinosaurs return to Earth

Similarly, the Jurassic Park franchise has fueled public interest in paleontology ever since the first movie aired in 1993. Like The Day After Tomorrow, Jurassic Park and its sequels have plenty of scientific inaccuracies. But they also get some key things right about dinosaurs, says Gabriel-Phillips Santos, the director of education at the Raymond Alf Museum of Paleontology in Los Angeles.

Beginning in the first movie, Santos says, T. rex walked with a realistic gait, its tail sticking straight out and its body parallel to the ground, despite earlier pop culture depictions of a more Godzilla-like T. rex that stood upright with its tail trailing behind. Brachiosauruses, meanwhile, are depicted walking out of the water and onto land in a way that aligns with paleontologists' thinking about how their lifestyle evolved, Santos says.

“We used to think they were so heavy they could only support their weight in the water, but we now know that’s not true. They kinda showed [that] on screen.”

Even when the films aren’t scientifically accurate—the velociraptors are way too large, and the franchise didn’t introduce a feathered dinosaur until 2022, despite reams of scientific evidence that that many dinosaurs had feathers—Santos says they offer an opportunity to reach audiences he wouldn’t otherwise be able to reach. He frequently gives talks at pop culture conventions, like San Diego Comic-Con, about the real (and fake) science of the Jurassic Park franchise.

“Anything that involves dinosaurs that makes it into popular media… it’s going to inspire [people]”, Santos says. “It can inspire them to go to a natural history museum and learn more. If they decide to go into the field, that’s amazing.”

Space travel

The Star Trek franchise, which has inspired multiple generations of kids to become astronomers and space explorers, likewise blends real science with a healthy dose of exaggeration. Astrophysicist and Star Trek science advisor Erin MacDonald says that she often uses Star Trek: Voyager, which aired from 1995 to 2001, to explain scientific concepts, like how gravity distorts spacetime, to convention audiences.

“It’s surprisingly a really science heavy show,” MacDonald says.

MacDonald, who earned her PhD studying gravitational waves before pivoting to a career in science communication, was first hired by Star Trek to come up with a scientific explanation for “The Burn,” a cataclysmic event introduced in Season 3 of Star Trek: Discovery, in which all of the galaxy’s active "dilithium" goes inert, rendering warp travel impossible.

MacDonald drew on real scientific fields, like particle physics and the study of dark matter, to explain why dilithium, a fictional material, would suddenly stop behaving the way it always has in Star Trek. MacDonald now gives feedback on every Star Trek series that’s airing or in production, reading scripts and suggesting language changes, writing equations that will appear on screen, and working with post-production teams to help get any science visuals right.

Global pandemics

The 2011 bio-disaster thriller Contagion also solicited input from scientists—and it shows, says Tara Smith, an epidemiologist at Kent State University. In the film, public health officials scramble to research and contain a novel virus that jumped from bats to pigs to humans, rapidly fueling a global pandemic. Smith, whose research focuses on zoonotic infections—or infections that move from animals to humans—says that virus in Contagion has a transmission pathway very similar to that of the Nipah virus, which has spread from bats to pigs to people.

“The pandemic went a little faster than you would expect in real life—zero to pretty much all around the world in just a few days,” Smith says. “Vaccine development was also incredibly fast. But it was more reasonable as far as infectious disease movies go.”

Smith also praised the first season of the TV series The Last Of Us, which aired on HBO earlier this year, for linking climate change to emerging infectious disease outbreaks in a way that’s “pretty scientifically rigorous.” The show depicts a post-apocalyptic future in which a worldwide fungal infection has transformed much of the human population into zombies, triggering the collapse of society. The zombies are “where the biology stops,” Smith says. But the opening of the show features a scientist talking about how, as the Earth warms and fungi become adapted to higher temperatures, outbreaks of fungal disease could become more widespread—an idea that has scientific merit.

“I used that in my infectious disease epidemiology class last year to talk about climate change and emerging disease,” Smith says.

(Learn more about the fungus featured in The Last of Us.)

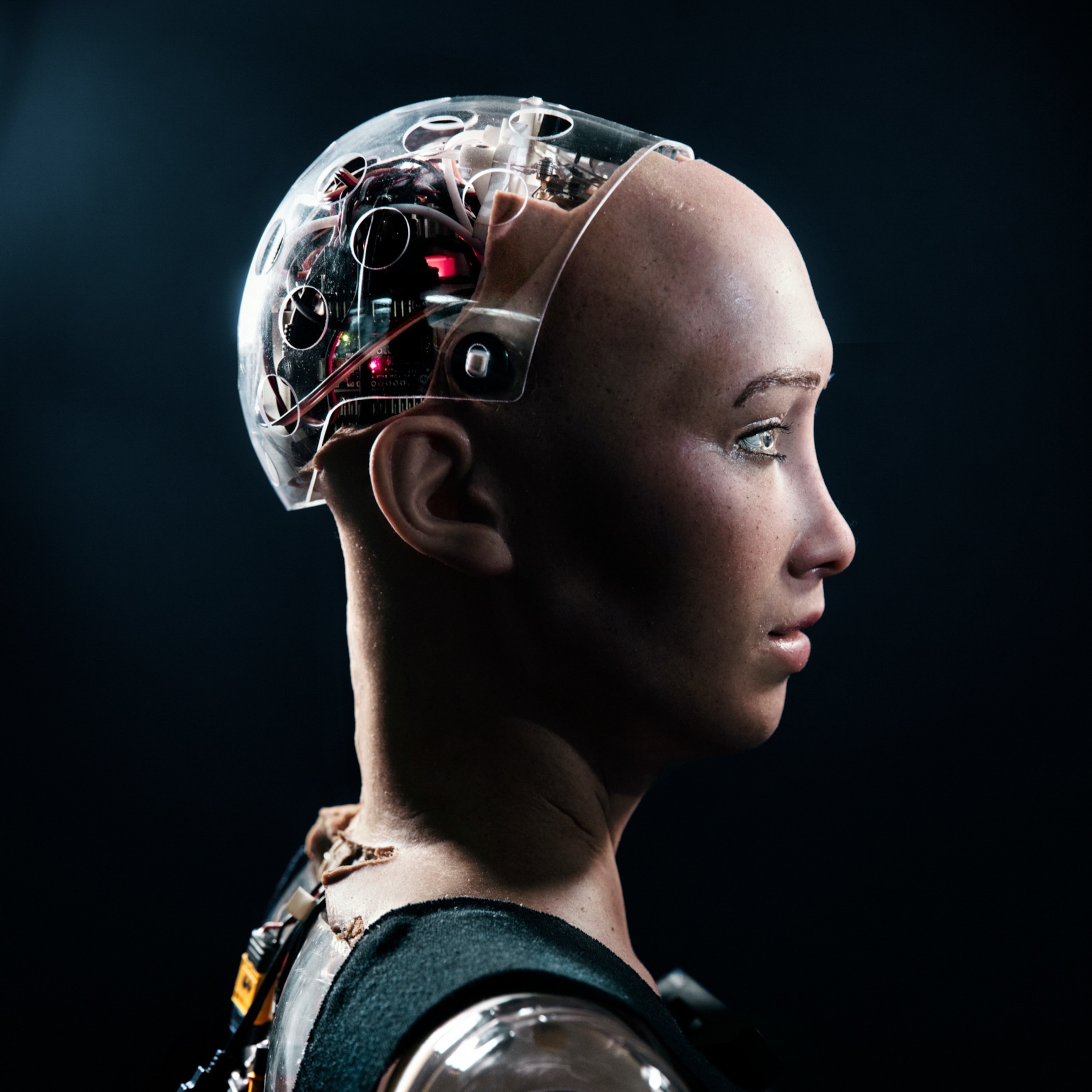

The rise of artificial intelligence

Some scientists, like artificial intelligence researcher Janelle Shane, are still waiting for Hollywood screenwriters to depict their field in a realistic way. While AI plays a central role in many blockbuster films and TV shows, from Terminator and The Matrix to Battlestar Galactica and Apple TV+’s Foundation series, most depict robots that have achieved consciousness and a human-like level of intelligence.

That’s a far cry from the AI-based technologies we see in our world today, like Apple’s voice assistant Siri and the software that guides self-driving cars. While some forms of generative AI, like ChatGPT, can write essays and tell jokes that feel unnervingly human, in reality, these are still simple programs optimized to do a specific task or set of tasks very well.

“Science fiction AI is AI that’s kind of like a person, or at least as smart as a person even if it has different worldviews and goals,” Shane says. “And real-world AI is something much more limited.”

Shane has seen a few examples of realistic AI popping up in recent sci-fi novels, like Robin Sloan’s Sourdough. The book centers on Lois Clary, a software engineer at a robotics company who’s struggling to teach a robotic arm to carry out specific tasks “and having a very realistic set of problems,” Shane says. Suddenly, her life is upended when her brothers gift her a sentient sourdough starter and tell her to keep it alive.

“It’s a great cozy read,” Shane says. “Especially if you can get a loaf of good sourdough bread to have while you’re reading it.”