Sunken shipwrecks tell the story of Alaska’s ‘forgotten’ WWII battlefield

U.S. and Japanese forces fought over the Aleutian Islands during World War II. Relics of this conflict can still be found on seafloor today, and the Indigenous people who used to call the islands home still feel the impact of displacement.

The moment in July when Wolfgang Tutiakoff's research ship first sighted Attu Island seemed almost sacred: "It was really emotional and quite literally breathtaking," she says. "About twenty people stood in silence for at least five minutes before someone said something."

Attu gets few visitors these days. No one lives there now, and the U.S. National Park Service monitors access. At the very end of Alaska's Aleutian Island chain, Attu is the westernmost territory of the United States—so far west, in fact, that it's technically in the eastern hemisphere and the International Date Line kinks around it.

In early June 1942, six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Attu and Kiska, another Aleutian island about 180 miles east, became the only parts of the United States ever occupied by an enemy when they were invaded by Japan. The occupation lasted for almost a year, until American and Canadian troops drove out the Japanese in May 1943—a grim campaign for both sides known as the Battle of Attu, when almost 3,000 people were killed and thousands injured, often because of the extreme cold.

Since the war, however, Attu and Kiska have mostly been uninhabited and are seldom visited—except for a few archaeological expeditions, like the one Tutiakoff worked on, which aim to document the vanishing details of Alaska's "forgotten battlefield."

Ancestral island

Maritime archaeologists Jason Raupp of East Carolina University and Dominic Bush, who's now with the nonprofit group Ships of Discovery, led the July 2024 expedition to Attu that searched for wrecks and other sunken relics aboard the research vessel Norseman II.

A student at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, Tutiakoff was one of two cultural liaisons from the Qawalangin tribe of the Unanga (Aleut) people. The Unanga people had lived on the Aleutian Islands for thousands of years, and her main task was to provide cultural context, especially from tribal histories, for the expedition's scientific discoveries.

The voyage was also a personal pilgrimage of sorts: In the wake of the Japanese bombing of the Aleutian town of Dutch Harbor on June 3, 1942, Tutiakoff's grandfather—then a child—was one of almost a thousand people evacuated from Attu and other Aleutian Islands by U.S. authorities and relocated to squalid huts in the Alaskan Panhandle. In addition, about 45 Unanga people were captured on Attu during the Japanese invasion and taken prisoner; only about half of them survived the war.

Despite the war's eventual end, the Unanga were never allowed to return to Attu; instead, the U.S. military occupied the island after the Japanese were driven out, and it was eventually abandoned—except for a Coast Guard station that closed in 2010. The U.S. military also contaminated parts of the island with toxic chemicals.

Attu is now part of a National Monument, and while it's legal to visit, the former residents and their families are still not allowed to live there. For Tutiakoff, just seeing the remote island was an important event. "It is so magical," she says. "It's a gigantic island, with mountains and tundra and rocky beaches… It's covered in beach grass that's not only green, but neon green… It looked like a unicorn would walk out of it."

Searching for shipwrecks

The team searched the waters around Attu for 11 days. The Aleutian Islands are infamous for storms, high winds, rain and fog, but Raupp recalls that they were blessed with unusually clear and calm weather.

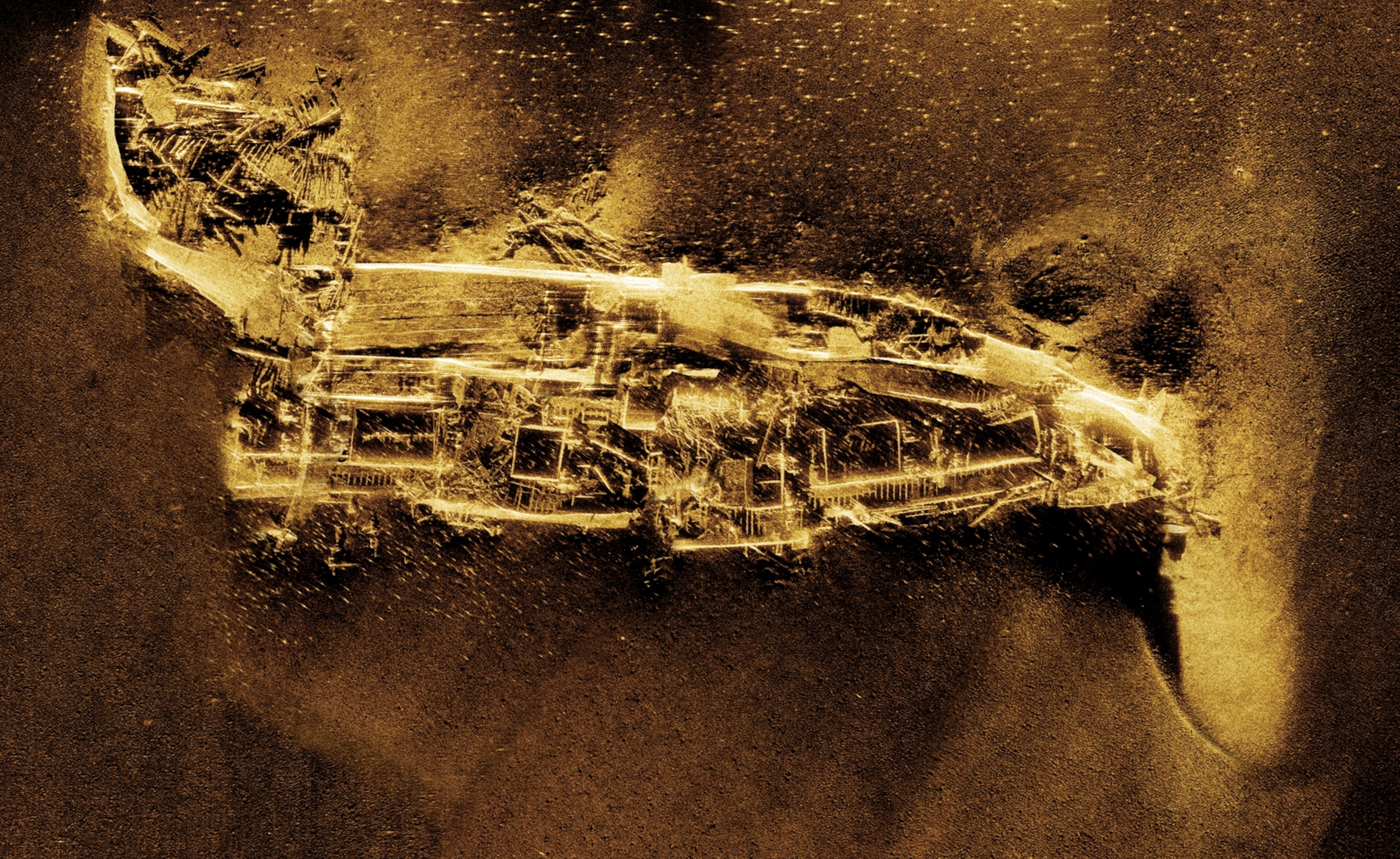

Using the latest in underwater search technology, the researchers discovered and documented three wartime wrecks—two Japanese freighters and an American cable-laying ship—in the waters around Attu. The researchers think the two freighters had been carrying supplies to the Japanese garrison, while the American ship dates from the months after the Japanese were driven out and the island's defenses were being strengthened.

(Archaeologists have also investigated Pearl Harbor’s wrecks. Here’s what they found.)

Expedition to Kiska

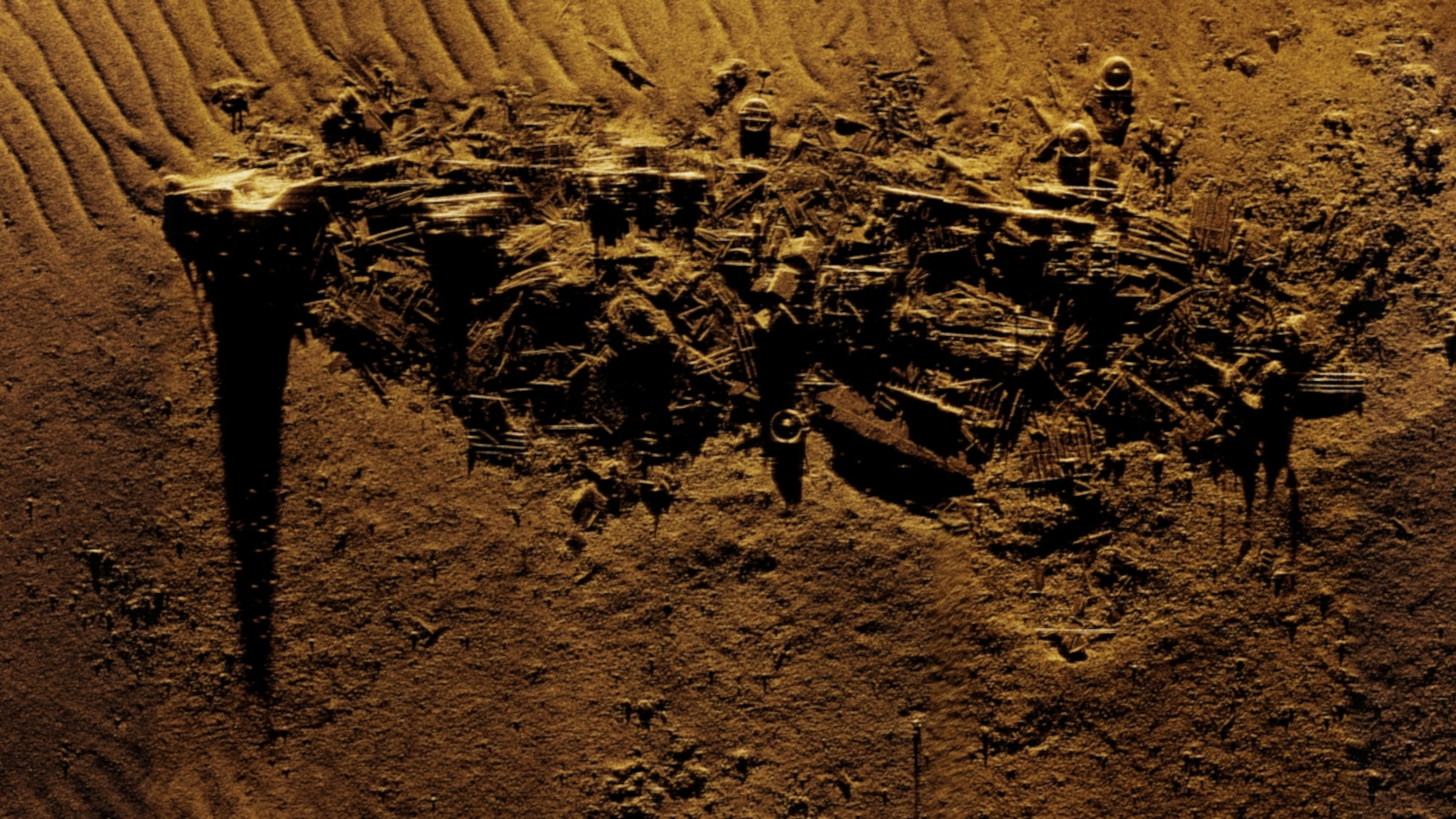

The Attu expedition echoes a similar expedition to Kiska in 2018 that culminated in the discovery of the stern of the USS Abner Read, an American destroyer severely damaged in August 1943 when it struck a Japanese sea-mine. The ship was saved, but 71 crew were killed at Kiska and dozens suffered severe injuries or inhaled toxic smoke. (It was later sunk in 1944, at the Battle of Leyte Gulf in the Philippines.)

The 2018 expedition also documented the wreck of an Imperial Japanese Navy submarine, designated I-7, which was badly damaged by gunfire from an American destroyer in June 1943 and deliberately run aground on rocks; the scuttled wreck of a Japanese two-man "midget" submarine, intended to torpedo enemy warships; and pieces of an American B-24 Liberator bomber that was hit by antiaircraft fire while attacking Japanese positions on the island.

Supply by submarine

A scientific report of the Kiska expedition was published last month in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology.

"Our approach was to survey and document what the underwater battlefield looked like," says lead author Andrew Pietruszka, a maritime archaeologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego who led the expedition. Important archaeological surveys had been carried out on the battlefield islands "and that was inspirational for our work… we set out to replicate what they were doing on land."

The I-7 submarine wreck was especially notable. The Americans had been bombing the Japanese on Kiska since the invasion, so Japan tried to avoid air attacks by using submarines to supply the occupying garrison of several thousand soldiers. "The U.S. gained air superiority, and that made surface ship support more difficult," Pietruszka says. "So I think [the Japanese] began relying more on submarines for resupply, and that's what I-7 was doing when it was detected."

New tools

Both expeditions relied on underwater robots to map and search the seafloor.

The Kiska team spent two weeks on a research ship around the island and surveyed its main sites with sonar equipment on four autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) that operated independently of the ship-bound researchers. It was the first time that AUVs had been used around Kiska, and the study authors note they can chart much larger areas of seafloor in greater detail than traditional towed sonars, while several AUVs can operate continuously over a 24-hour cycle.

The researchers at Attu, however, worked with specialized lightweight remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) that were tethered to the research ship and provided live video from the dark depths. Bush says the real-time ROVs were preferable in some circumstances to AUVs, where the data in them needs to be "downloaded" after their recovery. Future maritime archaeological expeditions in the area will ideally use both technologies, he says.

(ROVs help scientists explore places that are too dangerous to dive.)

Learning more about Attu

New aspects of the Attu wrecks are still coming to light months later, as the masses of recorded data are newly processed by the expedition partners, including the Japanese World Scan Project that developed its ROVs.

Historical research also hints at new details of Japan's wartime motivations for their invasion of the Aleutian Islands. Historians have usually seen it as a diversion for Japan's ill-fated attack on Midway Atoll, which had taken place a few days earlier.

But Bush says it seems Japan also hoped to use Attu as a base for air attacks further up the island chain and perhaps on the North American mainland—plans that never came to pass. "[The Japanese] came to think that taking over U.S. soil in North America would be advantageous from a strategic standpoint," he says. "They called Attu their 'unsinkable aircraft carrier.'"

The Attu expedition was also a learning experience for Tutiakoff, as well as an opportunity to share her knowledge with the researchers. She used part of the time to research her family history, and to assess the chances that the Unanga people could one day go back to live on Attu given the environmental hazards. "Returning is definitely a goal of ours," she says. "That's one of my missions that I want to accomplish: to reinhabit the island and bring it back to our people, so that we can grow as a community."