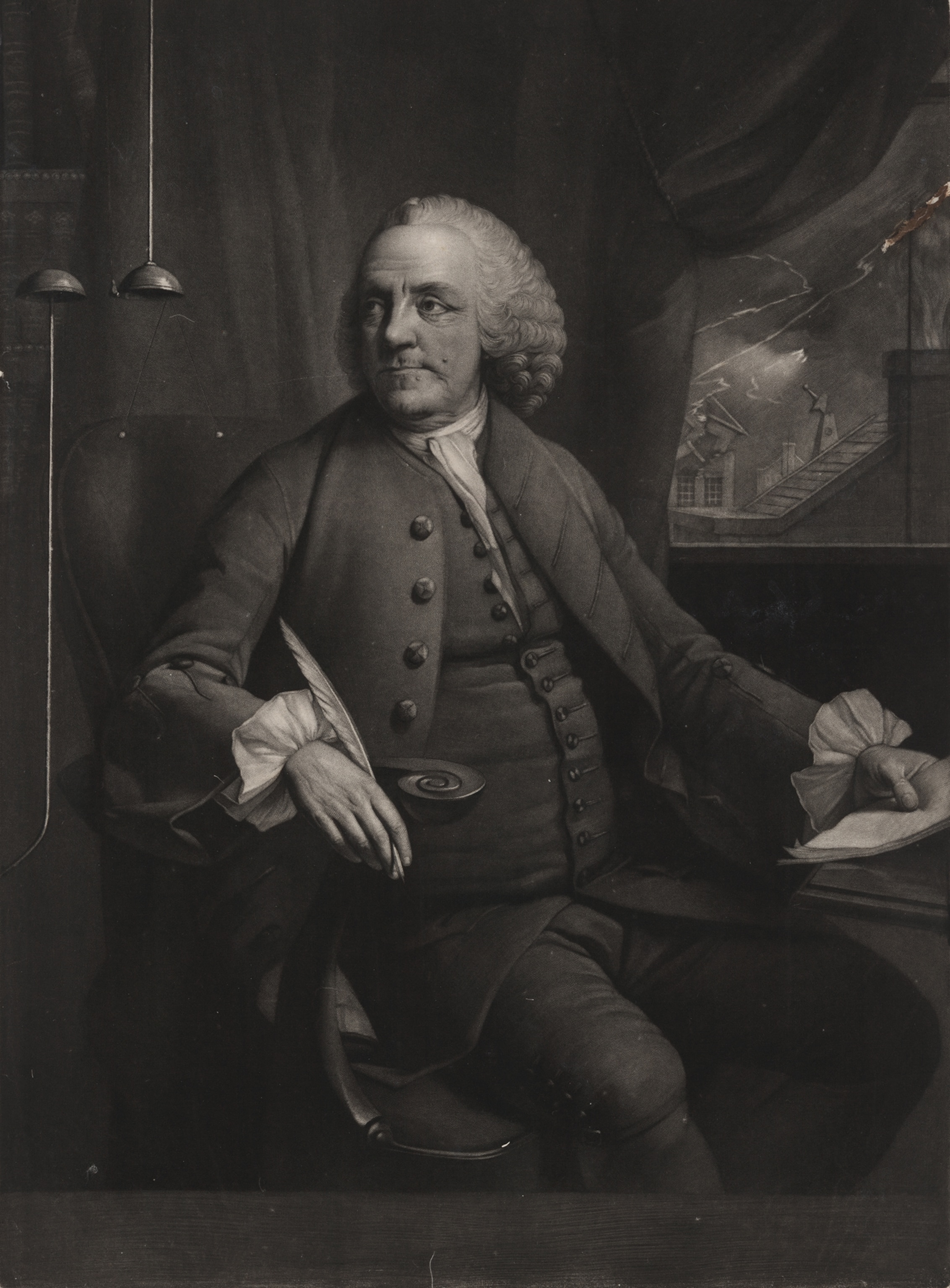

5 lessons Benjamin Franklin taught me about traveling well

The most widely traveled American of his time, the founding father learned a thing or two along the way.

As a young boy growing up in Boston, Ben Franklin liked to loiter at the local harbor. He’d watch the arriving ships, chat with the sailors, and dream of joining their ranks. That dream never materialized—but Franklin, an American founder, groundbreaking scientist, statesman, and writer, did go far.

He was the most widely traveled American of his time, logging 42,000 miles over the course of his long life. (He died at age 84.) He crossed the Atlantic eight times. As deputy postmaster, he traveled the entire length of the Northeast. He spent a third of his life abroad, living in London and Paris, and visiting Canada, Ireland, Scotland, Germany, the Netherlands, and, for three glorious days, the Portuguese island of Madeira.

Travel enabled him to cast his gaze beyond Puritan Boston and imagine fresh possibilities. What advice might the peripatetic founder offer us modern-day travelers? Here are five lessons, culled from Franklin’s writing and his life, and which I explore in my new book, Ben & Me: In Search of a Founder’s Formula for a Long and Useful Life.

Movement stirs the imagination

In one of the many contradictions that defined Franklin, travel enabled this most restless of souls to pause—and think. He did some of his best writing and experimenting while on the road or at sea. It was on a bumpy carriage ride from Philadelphia to Albany, New York, in 1754 when he composed his brilliant and prescient plan for colonial unity. It was on an Atlantic crossing to London in 1757 when he wrote his famous “Father Abraham’s Speech” (later retitled “The Way to Wealth.”). On another Atlantic crossing, to Philadelphia in 1774, Franklin’s opposition to British rule gelled and, at age 69, he became a fervent American rebel.

Franklin joins a long list of creative people who found inspiration on the road, from Charles Dickens to J.K. Rowling. There is something about movement that stirs the imagination. As the Swiss philosopher (and Franklin contemporary) Jean-Jacques Rousseau said: “I can scarcely think when I remain still; my body must be in motion to make my mind active.” So, next time you leave home, bring a notebook and pen. You never know what ideas might arrive unbidden.

(He was a Founding Father. His son sided with the British.)

All great travelers are great actors

On the road, far from family and expectations, we feel lighter, and free to play different roles. No one knew this better than Benjamin Franklin. He slipped in and out of character as effortlessly as Tom Hanks. In London, he played the part of the proper English gentleman; in France, wigless and wearing a marten fur cap, he transformed himself into the folksy, backwoodsman philosopher. (The French ate it up.)

Franklin knew he was playacting, wearing sundry masks, and winks at us while doing so. He was what the philosopher Alan Watts called a “genuine fake.” Genuine fakes are not con artists and they are not deluded. Genuine fakes so fully inhabit their role—their roles—there is no distance between part and person, mask and face. Next time you’re on a journey, try on a mask or two. What do you have to lose?

Improvisation can rescue a journey

Franklin was an accomplished swimmer, at a time when few people, not even sailors, could stay afloat. He swam in Boston’s Charles River and later in London’s Thames and Paris’s Seine.

He plunged into other kinds of unfamiliar waters, too. He took chances while traveling, and embarked on journeys when the outcome was far from certain. When he ran away from home at age 17, he had no idea what awaited him in New York or Philadelphia. In 1757, he traveled to London for what he thought would be a six-month assignment. He ended up staying for 17 years. Later, when the ship carrying him to France encountered uncooperative winds and couldn’t dock, Franklin commandeered a fishing boat to take him ashore. When leaving France eight years later, and too sick to make the carriage ride from Paris to the seaside town of Le Havre, he convinced the French queen Marie Antoinette to lend him her personal litter.

As a traveler, Franklin made plans—he was a methodical person, after all—but always remained flexible. He was a master of improvisation, one of the key tools in any traveler’s kit.

Not all destinations are equally good

As a young man, Franklin drew up a list of 13 virtues he intended to follow. One was sincerity, or honesty. And that he was, especially when it came to travel. He was finicky. He knew what he liked and what he didn’t. Had Tripadvisor existed then, he would have been every hotelier’s worst nightmare. In France, he chastised innkeepers for poor service. In England, he described a Portsmouth hotel as a “wretched inn,” where even the stationery was shoddy. He called the town of Gravesend “a cursed biting place”, whose inhabitants expertly relieved travelers of their money.

Yet when he liked a place, he was equally vocal. During a six-week visit to Scotland, he experienced the “densest happiness” of his life. On a trip to France, in 1767, he effused about the beauty of Versailles. “The range of building is immense, the garden front most magnificent…the number of statues, figures, urns, in marble and bronze of exquisite workmanship is beyond conception.”

Franklin knew that travel demands discernment; not all destinations are equally good, and that to love every place is to love no place. His advice: Call them as you see them.

Bad trips can turn into great ones

We’ve all had bad trips, journeys where, despite our best planning and intentions, everything goes wrong. Franklin had his share of bad trips, too—an ill-fated journey to Montreal at age 70 nearly killed him—but he didn’t fret or sulk about them. He converted them into something useful: fodder for one of his many essays, perhaps, or a good tale to tell friends over a glass of Madeira.

(Why bad trips can make for great stories.)

One bad journey proved transformational. Only 20 years old, Ben was sailing from London to Philadelphia. The ocean crossing was plagued from the beginning. At one point, a shark circled the ship, forcing Ben to skip his daily swim. Onboard, a card cheat was uncovered, as well as a reckless cook who depleted their food reserves. The winds blew infrequently or, when they did, from the wrong direction. A journey that should have taken four weeks took 13.

With time on his hands, though, Franklin decided to reform himself. He devised a “Plan of Conduct” and vowed that “henceforth, I may live in all respects like a rational creature.” His plan consisted of four simple rules. Pay what you owe. Say what you mean. Focus on what matters. Treat people kindly.

Franklin had departed London one person and arrived in Philadelphia another. He knew that every bad journey contains the seeds of a very good one.