Crafted in Tohoku: meet the makers of Japan's most prized talismans and artisan treasures

From flame-forged iron teapots to delicately painted akabeko cows, the traditional crafts of remote northern Honshu island are as unique as they are collectable.

Largely disconnected from the high-speed whizz of Japan’s big urban centres, the region of Tohoku in the far north of Honshu island has long been associated with folk art, crafts and talismans — made by hand and perfected over centuries by generations of artisans. Here in deep Japan, where rice paddies surround isolated houses and torii gates mark forest boundaries, these caretakers of tradition are making some of Japan’s most cherished treasures

Nanbu ironware

Morioka, Iwate Prefecture

Morioka’s artisan ironware trade has stood the test of time far better than the feudal dynasty that spurred it into existence. The Nanbu clan’s castle lies in ruins, its fortifications demarcating what is now a vast garden complex of shrines and Edo-era relics in the city centre. My destination nearby is a studio where descendants of 17th-century artisans still labour in cotton vests over an open furnace stoked to 1,500C.

“This studio was founded in 1625 and I’m the 16th generation,” says Shigeo Suzuki as he leads me past shelves of cast-iron teapots and Buddhist ornaments, down a passageway to a single-storey workshop behind his gallery. Ironware craftsmen were invited to settle in Morioka 400 years ago by ruler Nanbu Toshinao, to work with abundant iron ore deposits found in the rivers. “Nanbu designated four families to make utensils for his tea ceremonies. Only two are left, and we’re one of them,” he adds.

The air inside the workshop has the sharp metallic tang of iron. Columns of rotund teapot moulds, made from a mix of clay, sand and mud, cover the right-hand wall. To my left are warped shelves with hundreds of design plates stacked like sheets of paper. “The process is similar to pottery,” says Suzuki. The metal plates are used to create an imprint inside the moulds, which are then baked over charcoal. Molten metal is poured into the moulds to make teapots. “I can produce a teapot design that’s over 100 years old, as long as I have the plate,” explains Suzuki, pulling down a dusty metal sheet no thicker than a piece of cardboard.

Nanbu ironware is prized for its quality and durability. The traditional production techniques create an oxide layer; when a Nanbu kettle is boiled, iron elements filter into the water, making a cup of tea act as a natural iron supplement. At the Iwachu factory in Morioka, visitors can see the Nanbu teapots being forged and buy one for as little as ¥9,000 (£50). But here, partly because of Suzuki’s provenance, prices can hit ¥800,000 (£4,420).

Suzuki’s great-grandfather was designated a living national treasure in Japan in 1974, because of his role in petitioning the government to let Nanbu production continue during WWII — an act that is believed to have prevented the industry from dying out in the 20th century. Suzuki’s mother is also a trailblazer, having become the first woman to train as a Nanbu ironware artisan. Now it is his turn to make his mark, by taking on the family title of morihisa — master artisan — in a ceremony next year.

“I want to be innovative while keeping the traditional styles and ways of making,” he says. “It’s been proved that this is still the best way to make these products — even after 400 years.”

Iwachu and Suzuki Morihisa are in central Morioka. Into Japan can organise tailormade trips , including craft itineraries in Tohoku and beyond. An eight-day tour with accommodation, transport, some meals and tours, but not international flights, costs £14,000.

Kokeshi dolls

Naruko Onsen, Miyagi Prefecture

The air is spiked with sulphur from Naruko’s thermal vents as I enter the Sakurai Kokeshi workshop. Curtains painted with bulbous kokeshi heads are fluttering from wooden beams above shelves of dolls made of dogwood, pagoda-tree and cherry wood. Curlicues of shavings have collected in the corners of window frames by the studio door. There’s a high-pitched whir from the metal lathe, spinning furiously as fifth-generation artisan Akihiro Sakurai stoops over his carpentry perch.

The pretty onsen town of Naruko is synonymous with the art of kokeshi making, which the Sakurai family has been perfecting for more than a century. The Japan Kokeshi Museum is here, alongside private galleries, kokeshi-themed street art and a Kokeshi Cafe. Visitors come from all over Japan to shop in Naruko’s studios and soak in steaming, mineral-rich baths.

It’s widely believed the inspiration for early kokeshi came from ceramic cradle dolls that were fashionable for babies of noble birth in the 18th century. Communities across Tohoku — a densely wooded region — started making naive-style, poor-man’s versions with local woods in the 19th century. They would sell them to tourists in the onsen towns during winters when work was scarce.

An interesting aspect of these figurines — besides the fact they have no limbs — is that their painted hairstyles, facial features and decorations are singular to the town in which they are created; sometimes even to the maker. The merest flick of an eye or snub of a nose are clues as to which town and studio a doll was crafted in, like a fingerprint.

“Traditional kokeshi making is special because it’s a connection to my ancestors,” says Sakurai, absentmindedly scooping up sawdust from his workbench and running it through his fingers as we talk. “When I was a kid, I liked to watch my family making them. My father and grandfather used to carve and my grandmother would do the painting.” But the family style has evolved over the decades, he says. “Making traditional kokeshi is similar to music. Like a music note, each generation has its own expression.”

In Naruko, signature characteristics include red chrysanthemums on the trunk of the body and a mizuhiki top-knot hairstyle, said to have originated with samurai warriors in the 17th century. Over time, members of the Sakurai family have added their own personal flourishes: more chrysanthemums, delicately sloping shoulders, and colours such as yellows and purples in addition to the traditional greens and reds.

Sakurai has also exhibited his creative kokeshi — highly artistic dolls that do not conform to the geographical characteristics of traditional kokeshi — in Milan and Paris, and won awards for them. If traditional kokeshi design is like playing music notes, he says, making creative kokeshi is like “being a singer-songwriter and making your own music”. In the past decade, Japan has seen a resurgence in the popularity of Tohoku’s kokeshi dolls and they are now sought after by collectors in Tokyo and as far afield as Europe.

When Sakurai is at the lathe, he rests his forearms on a plank to give him the steady hand he needs to work the wood with fluid movements. Naruko kokeshi are made in two parts. The most complicated action is scooping out a hole for the neck using a small drill, which he does by sight alone. Occasionally he stops, takes one of the round heads by his side and brings it into line with the body to see if it will match the neck hole. When he finally attaches a head, he twists it to make sure it squeaks — an audible note that tells us it’s the perfect fit, not too tight or loose.

After this comes polishing and painting. Sakurai is one of the last studios in the area to still use tokusa (a local dried grass) and inakusa (dried rice leaves bought from local farmers) in the polishing process; the natural oils in them are said to lend a waxing effect.

Painting my own kokeshi is easier than I expected. There’s a step-by-step English instruction leaflet. A shop assistant turns a mini metal lathe that does most of the work as I hold a steady paintbrush to the kokeshi trunk, adding the signature coloured bands. It might not look exactly like Sakurai’s, but it’s my own indelible fingerprint, and that’s more than enough.

Kokeshi painting at Sakurai Kokeshi costs ¥2,500 (£14). Stay at Ryokan Ohnuma, a 120-year-old Naruko inn with seven onsen baths and an in-house restaurant. Doubles from ¥35,200 (£195), half board.

Akabeko

Aizu Wakamatsu, Fukushima Prefecture

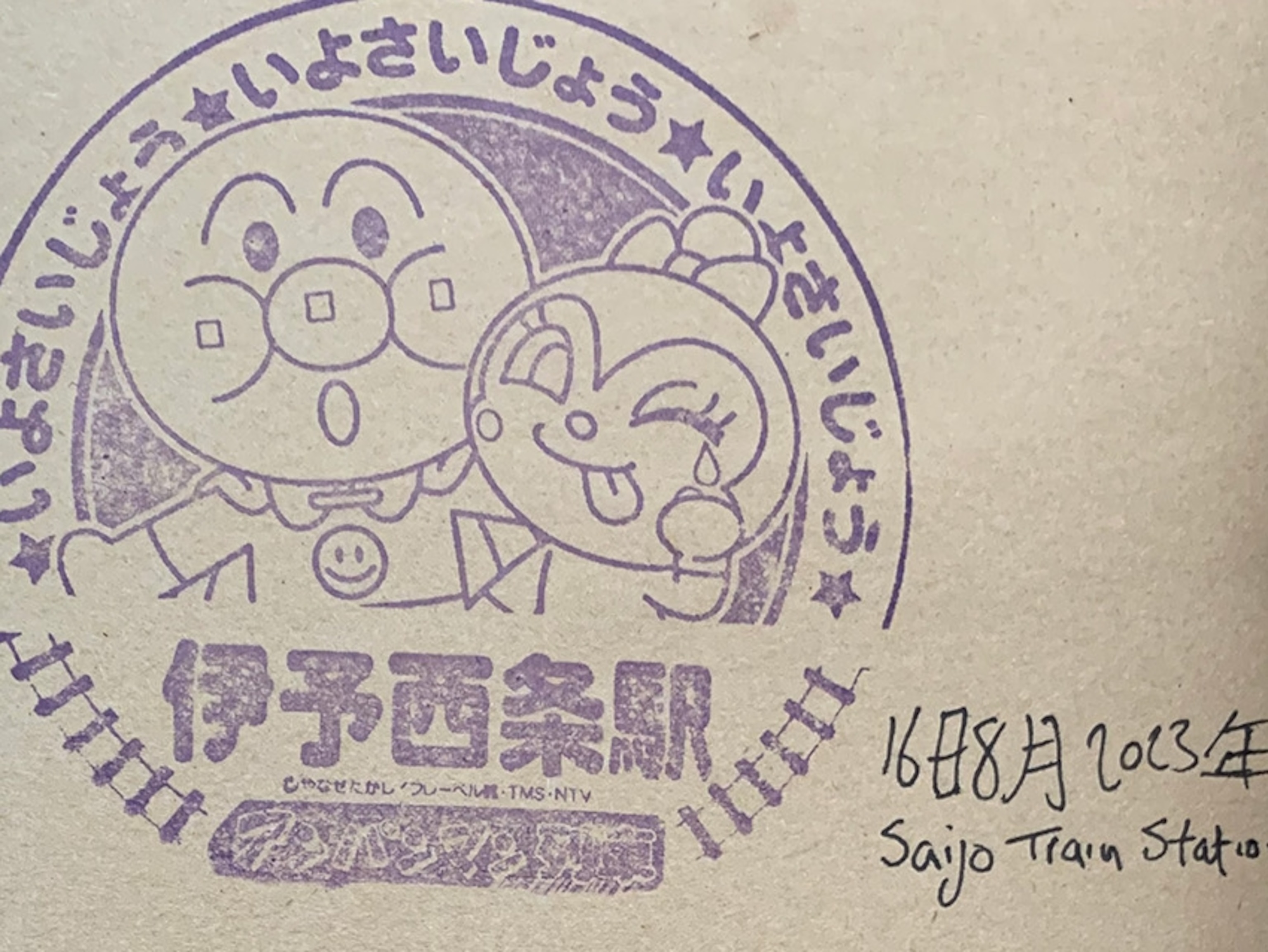

Pulling into Aizu Wakamatsu by train, it’s impossible not to notice the town’s unofficial mascot standing guard on the station platform. It appears again many times in quick succession — flashes of lipstick red on stickers in the bathrooms, a giant rump in the car park, delicate horned figurines inside the restored, wood-panelled stores of Nanokamachi Street that now specialise in local crafts.

Written into Japan’s history books as one of the last samurai strongholds to stand against the Meiji restoration during the country’s opening to the world in the 1860s, today the castle-topped town of Aizu is also famous as the home of Fukushima’s red cow, akabeko. It’s unclear where exactly the origins of the lucky talisman lie, but the web of myths and legends surrounding it are certainly more complicated than the figure itself, with its buxom glossy flanks and simple bobbing head.

The most commonly held story suggests akabeko first made an appearance around 1,200 years ago, during the construction of the Enzoji temple (still in existence today) 12 miles away in Aizu Yanaizu. Among the cattle used to carry timber to build the Buddhist structure’s main hall, a cow with red hair was particularly celebrated for its hard work. The night the hall was completed, the cow is said to have magically turned to stone, becoming the temple’s guardian deity. Locals started making akabeko models to pay respect to the sacred bovine.

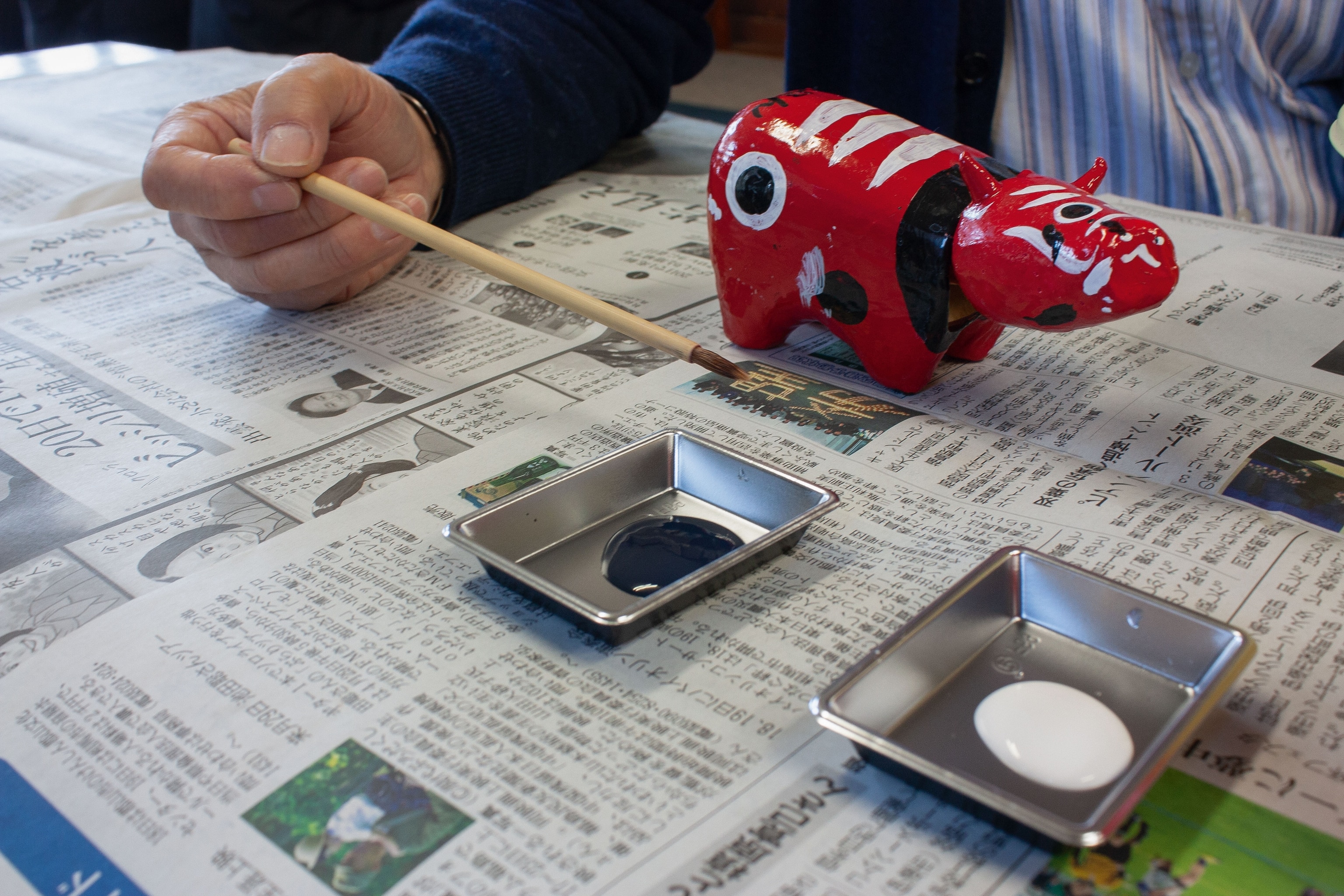

This is the story I am told when I join 75-year-old Shigeo Sudo at his Bansho workshop in Aizu Wakamatsu. A sucker punch of paraffin-based paint fumes — which Sudo seems completely impervious to — filters down from the first-floor manufacturing room, where a team of four full-time workers coat papier-mache castings with syrupy, high-gloss red paint.

“I think it’s important to pass this tradition to the next generation,” says Sudo. “When I was younger there were five or six shops manufacturing akabeko in Aizu. Currently there are only two. We’re facing a shortage of akabeko and I’ve made it my mission to fix this.”

One person can paint 200 cows a day — but the production takes two weeks from start to finish. Not because it’s technically difficult, but because of its many layers. It involves casting the cow in papier-mache from a local chestnut wood mould, applying a base layer primer, coating it in red and then finishing it off by adding its signature decorative markings. Sudo says that in the past, craftspeople would have used urushi — the coveted tree sap Japan harvests to produce some of its most prized lacquerware — to paint akabeko, but it’s now considered too expensive. “The cows in this shop cost ¥1100 [£6], but would cost ¥10,000 [£55] if we still used urushi,” he explains.

Sudo has been making akabeko for 50 years, and these days he usually focuses on the most skilful parts of the production process: applying the cow’s decorative black, white and gold markings with a steady hand. “I know there are a lot of people selling akabeko cows online in different colours, but I’d like to stick to the traditional colours,” he says. “The red has a special meaning — it wards off evil.”

Some of the decorative markings have symbolism, too. The black spots on the cow’s flanks are said to have become a regular design feature in the 1800s after the region suffered a smallpox epidemic. Children who owned akabeko appeared to escape the disease, leading people to believe that the toys had protective powers. Today they are still perceived as a talisman for good health, as well as easy childbirth.

Fitting snugly in the palm of my hand, the red papier-mache casting is smooth to touch and light as a feather. I have a go at painting an akabeko and, supplied with red, white and black paint, I decide to follow tradition. I add wobbly circles around the horns, black stripes down its back and white curly whiskers on its elongated cheeks. “Kawaii!” shouts Sudo — ‘cute’ — when he comes to inspect my work.

Before I leave, my cow dried and packaged in a cardboard box, I have one final question: if I give the akabeko away, will it be bad luck for me? “Don’t do that!” he warns, wagging his finger at me. “Please take care of the cow.”

A two-hour akabeko painting experience at Bansho costs ¥1200 (£7). Stay at Hotel Ookawaso, a 30-minute drive from Aizu, to experience the local onsen culture. It has a series of public and private outdoor baths overlooking a river valley, kaiseki cuisine and an on-site shop selling local crafts. Doubles from ¥14,450 (£80), B&B.

Maki-e lacquerware

Aizu Wakamatsu, Fukushima Prefecture

Purple glasses balanced on the end of his nose, an iridescent smudge of dragonfly blue on his cheek, Namio Nakamura reminds me of a magpie coveting treasure as he inspects the bowl in his hand. Two delicate maple leaves on its surface are catching his eye, their shimmering leaf veins rendered in emerald green and bronze. “Maki-e is the glamorous part of lacquerware,” he says, when I ask him what he loves about his job as an artist at Aizu’s Suzuzen factory. “Silver, gold, platinum — using those colours as an ingredient, that’s so glamorous.”

The intricacy of the designs is another aspect he says he enjoys, comparing his work to that of a craftsman making a Swiss watch.

Maki-e is a form of lacquerware art that involves painting with thin layers of starch glue to apply patterns of dazzling coloured powders onto bowls, plates, chopsticks and all manner of wooden items. “The decorative technique dates back to the emperor’s court of Kyoto in the 12th century, when owning elaborate maki-e became a status symbol,” Nakamura tells me, explaining that it was brought to Aizu when a feudal lord moved 50 craftsmen here from Kyoto in the late 16th century, to work with the abundant growth of urushi trees used in lacquerware making.

Suzuzen has been selling some of Tohoku’s finest lacquerware items since 1833, but that legacy is a mere drop in the ocean for one of Japan’s oldest craft traditions. “Excavations have shown people were using urushi lacquerware in Japan as long as 9,000 years ago,” says Nakamura. Though it might look like an artform, it’s always had a practical purpose as a means of protecting wooden buildings and everyday utensils from inevitable degradation. “In Europe you use stone, but Japan is covered in forests so we have always used wood,” he says.

I’m at Suzuzen — a quaint single-storey complex of wooden buildings with internal gardens, a lacquerware museum and cafe — for a maki-e workshop. Nakamura and I are both wearing soft slippers, and are hunched over a table as he deftly demonstrates the delicate touch needed to apply the glue to the maple leaf, firmly press it onto the bowl and then gently peel it off to reveal a thinly etched impression of the leaf veins.

It looks decidedly simple, but when I try it myself I quickly start to feel like a bull in a china shop. Nakamura’s instructions come thick and fast. “Less glue,” he warns, as I slosh the paste onto the maple leaf. “Gently, gently,” he says as I press the shimmer dust onto the glue with a fine paintbrush, having chosen my colour palette from a rainbow of boxes. And, finally, “rub harder!” as I use a bamboo-fibre cloth to remove any powder excesses and reveal my artwork.

Maple leaves are just one of the motifs used in maki-e decoration taken from Japan’s indigenous flora and fauna. “I picked the leaves this morning from over there,” says Nakamura, sliding back a wooden latticed door to point at a low-hanging maple tree bathed in midday sunshine. Bamboo, pine trees and orchids are also common in the designs, as are cranes and turtles — both symbols of longevity in Japanese culture because of their long lives.

Across town, I find a group of artists who have deliberately shied away from tradition, hoping to breathe new life into Aizu’s lacquerware craft. Masakuni and Chihiro Seki moved back from Tokyo to set up their contemporary design emporium and cafe Tenneiji Soko in 2022, inside a disused lacquerware factory. Racks of hand-stitched kimonos sit beneath metal rafters painted akabeko red, alongside contemporary lacquerware cups arranged on wooden pallets and a display of sustainable camping chairs and foldaway tables made of urushi wood.

“The process of collecting urushi sap and using it to make lacquerware is time-consuming, labour intensive and expensive, so it’s not used so much these days,” explains Masakuni Seki as he leads me out the back of the hangar-style building to show me a bundle of logs resting against a shed, etched with lines from where he has been drawing sap to make his own works. The alternative to urushi is synthetic lacquer, but Seki — a third-generation Aizu lacquerware artisan — is experimenting to make natural lacquer more affordable. His designs are pared-back and contemporary, and he applies fewer layers of urushi to give a matt — rather than traditional high-gloss — finish.

Over an organic lunch of panko-crusted pork cutlet with cabbage, and club sandwiches made with bread baked on-site in the cafe, Seki explains his thinking. “We want to eat food without artificial enhancements, but we use the lacquerware every day too, so it should also be natural. I’d like to teach people about an organic lifestyle. It’s a little bit expensive, but it’s important.”

Suzuzen’s one-hour maki-e lacquerware painting workshop costs ¥2,600 (£14.50). Stay at Hotel Ookawaso, mentioned previous page.

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).