How did the bluebonnet become a symbol of Texas?

Beautiful, abundant, and surprisingly hardy, these legendary blooms captivate flower lovers.

Waves of bluebonnet flowers fill Texas highways and backroads each spring. This inspires parents to snap photos of their kids in fields of purplish blooms, and road trippers to trek from Big Bend National Park to the Texas Hill Country in search of the enchanting wildflowers.

The blooms are mostly indigo, though bluebonnets also come in shades of pink and white. From mid-March to April, they pop out, bookended by other seasonal flowers— pristine white prickly poppies, dreamy evening primroses, lavender-hued Texas thistles.

How the little plants became such a big deal is a story as wide-ranging as the Lone Star State itself. Here’s how they came to be, where to see them, and why they need help now.

What’s a bluebonnet?

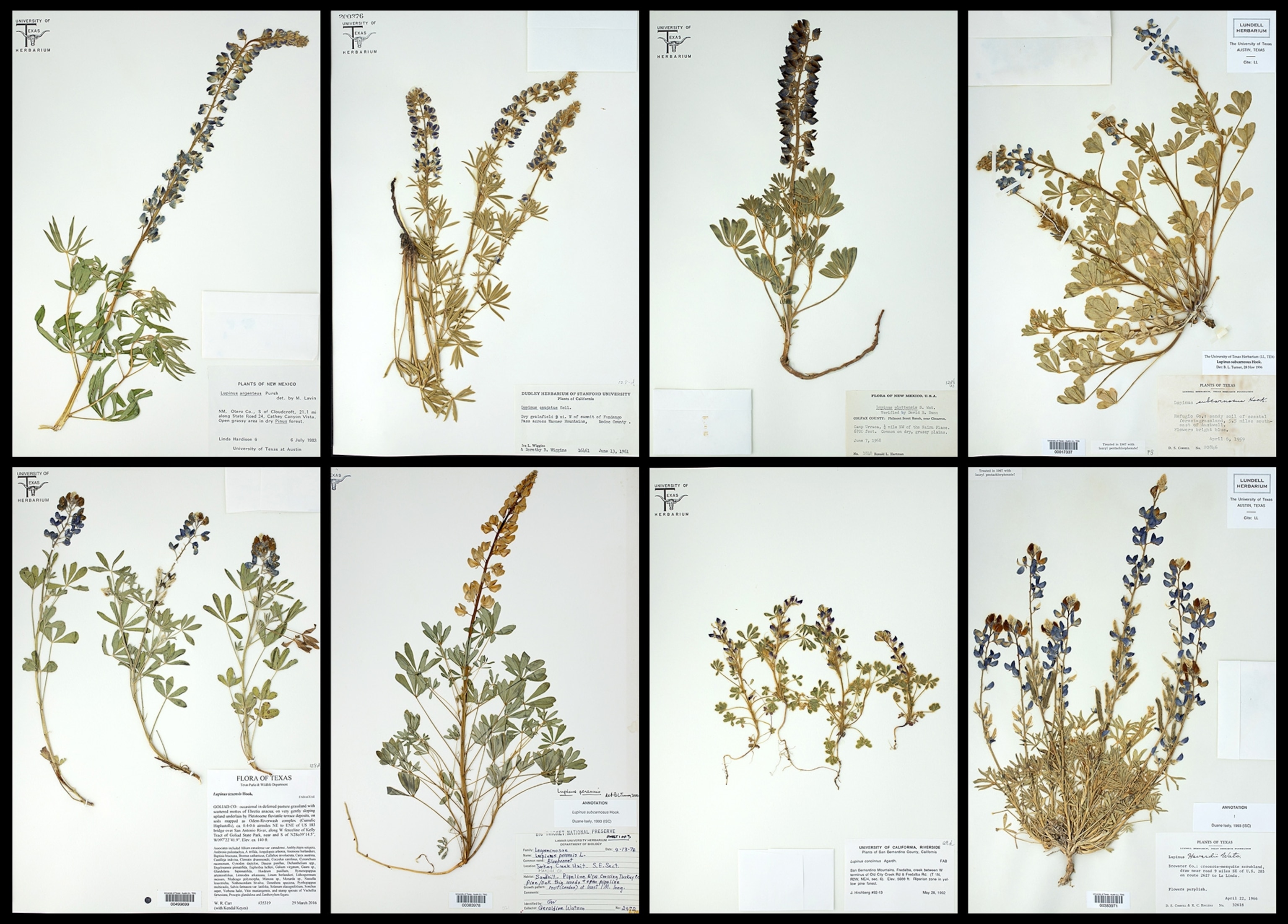

Texas has eight types of bluebonnets, the smaller Lupinus subcarnosus and the showier, larger Lupinus texensis being the most popular. Related to pea plants, they’re native to Texas and the southwest, and consist of clusters of mildly fragrant blooms on three- to six-inch stems. They’re annual plants, meaning they go from seed to flower and back again, germinating in the fall and winter before bursting forth—and spreading—again each spring. Why the name? People think they resemble old-fashioned women’s bonnets.

Though they often grow on their own in fields and natural areas, the swaths of blue along major highways and byways date to the 1930s, when the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) began planting them along roadways as beautification projects.

(Learn how flowering plants changed the world.)

Texas-born First Lady Lady Bird Johnson further promoted the concept of wildflowers in public spaces both while she lived in the White House (via the Highway Beautification Act) and afterward back home in the Hill Country. “She recognized how important wildflowers were in creating a regional sense of place,” says Lee Clippard, interim executive director at Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, “supporting biodiversity (though it wasn’t called that then), saving resources, enhancing beauty, and lifting people’s spirits.”

Today, you can see the flowers in season and explore her legacy at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, a botanical garden in Austin.

“Very few flowers exhibit that true blue color in oceanic expanses,” says Andrea DeLong-Amaya, director of horticulture at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. “They only grow naturally in Texas, so what better plant could we call the state flower?”

How do the blooms survive?

Bluebonnets thrive in the alkaline, often-dry soil of Texas. On the sides of highways and easements, their dense foliage protects against erosion long after the blooms fade. “They’re a hardy plant” and able to withstand the state’s often searing temperatures, says Travis Jez, a vegetation specialist for TxDOT.

But will major climate-change events—like the record snow and ice in mid-February—impact the iconic blooms? Probably not.

“At the time of the storm, bluebonnet rosettes still hugged the ground tightly, benefitting from the heat stored in the earth,” says DeLong-Amaya. “The snow actually insulated plants [and added] a small amount of welcomed moisture in the middle of drought.”

The most concerning threat to the bonnets may be invasive species.

“TxDOT takes measures to control invasive species such as wild cabbage, Johnsongrass, and rye grass throughout the year,” says Jez. “The wildflowers are able to concentrate on growing and blooming in the spring, instead of competing for sun and water.”

(Invasive grass is overwhelming U.S. deserts—providing fuel for wildfires.)

It doesn‘t help that some grasses planted to feed cattle, such as King Ranch bluestem, can eat into the bluebonnet’s range, says Jason R. Singhurst, a botanist and plant ecologist for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

From legends to pop culture

Everything in Texas comes with a whopping big story or myth, and bluebonnets are no exception. One legend tells of the Comanche suffering from food scarcity after a harsh winter. Community members discussed sacrificing their most prized possessions to fire to appease angry gods. A young girl from the tribe threw her cornhusk doll trimmed with a blue feather into the flames; the next day the landscape was covered in blue flowers.

Another folktale speaks of the Native American Jumano people of Texas being mysteriously visited by a Spanish nun in a blue cloak. She shared her Christian faith with the Jumano before disappearing one night, leaving a field of deep blue flowers in her wake.

(Discover the origins of Texas’ proud independent streak.)

Over the past century, bluebonnets made their way into pop culture as well. In the 1970s, an interacial National Women’s Football Leauge team called themselves the Dallas Bluebonnets. There is even an official state flower song written by Julia D. Booth and composed by Lora C. Crockett (a relative of Davy Crockett), called “Bluebonnets,” which was adopted by the state in 1933.

The lyrics speak of the wildflower’s beauty during blooming season: “When the pastures are green in the springtime / And the birds are singing their sonnets / You may look to the hills and the valleys / And they’re covered with lovely Bluebonnets.”

Where to find them

In springtime, drive down any highway in Texas, and you’re likely to see large patches of bluebonnets, sometimes interspersed with other wildflowers such as giant spiderwort, blue-eyed grass, and Mexican buckeye.

While it’s illegal to pick or damage bluebonnets on state land (i.e., state parks) or private property, that’s not the case on roadways, where many bluebonnets are found. That said, conservationists don’t advise plucking the blue flowers—and parking along the highway is a safety concern.

The small towns of Texas provide some of the best bonnet peeping. Ennis, a 35-minute drive south of downtown Dallas, was designated in 1997 as the Official Bluebonnet City of Texas, and is home to the Official Texas Bluebonnet Trail. Every April visitors can drive 40 mapped miles through some of the best blooms in the state.

(Here are 10 beautiful flower destinations around the world.)

Further south in the Hill Country, Burnet hosts a Bluebonnet Festival each April with live music, food, and a crafts fair. Surrounding areas are also awash in blue in March and April, including the Bluebonnet House, an atmospheric, widely photographed 150-year-old stone structure in Marble Falls.

If you’d like help seeing the flowers, opt for a five-hour guided Bluebonnet Tour with Jason Weingart Photography just outside of Austin, Texas or use the National Geographic Texas Hill Country Destination Touring Map and Guide for must-see spots.

No matter where you chase bluebonnets in Texas, remember to watch your step. A wrong step here, a wrong step there, can bring death to the state flower and prevent it from reseeding the next year.

“We have to remember that we are only temporary stewards of land during our lifetime, and we need to share the knowledge and appreciation of Texas wildflowers and wildlife to maintain these amazing resources forever,” Singhurst says.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

While TxDOT and TPWD staff are doing their best to preserve Texas’ bluebonnets, they could do with some assistance from citizens. People can volunteer to monitor the effects of climate change on bluebonnets by joining The National Phenology Network.

Texas landowners can also join the fight. “Highway and county road right-of-ways—between the pavement and fence line where native vegetation still persists—are wonderful places to enjoy Texas wildflowers,” explains Singhurst. “Many Texas landowners are moving towards establishing conservation easements on their ranches or farms to protect the wildflower heritage of our state.”

Alex Temblador is an award-winning mixed Latinx author and travel writer based in Dallas, Texas.

Photographer Sam Tippetts, based in Austin, can be found wandering the roads of Texas.