Memories are crafted in wool in this tiny Russian republic

In Ingushetiya, a new generation of women is reviving the traditional art of felting rugs.

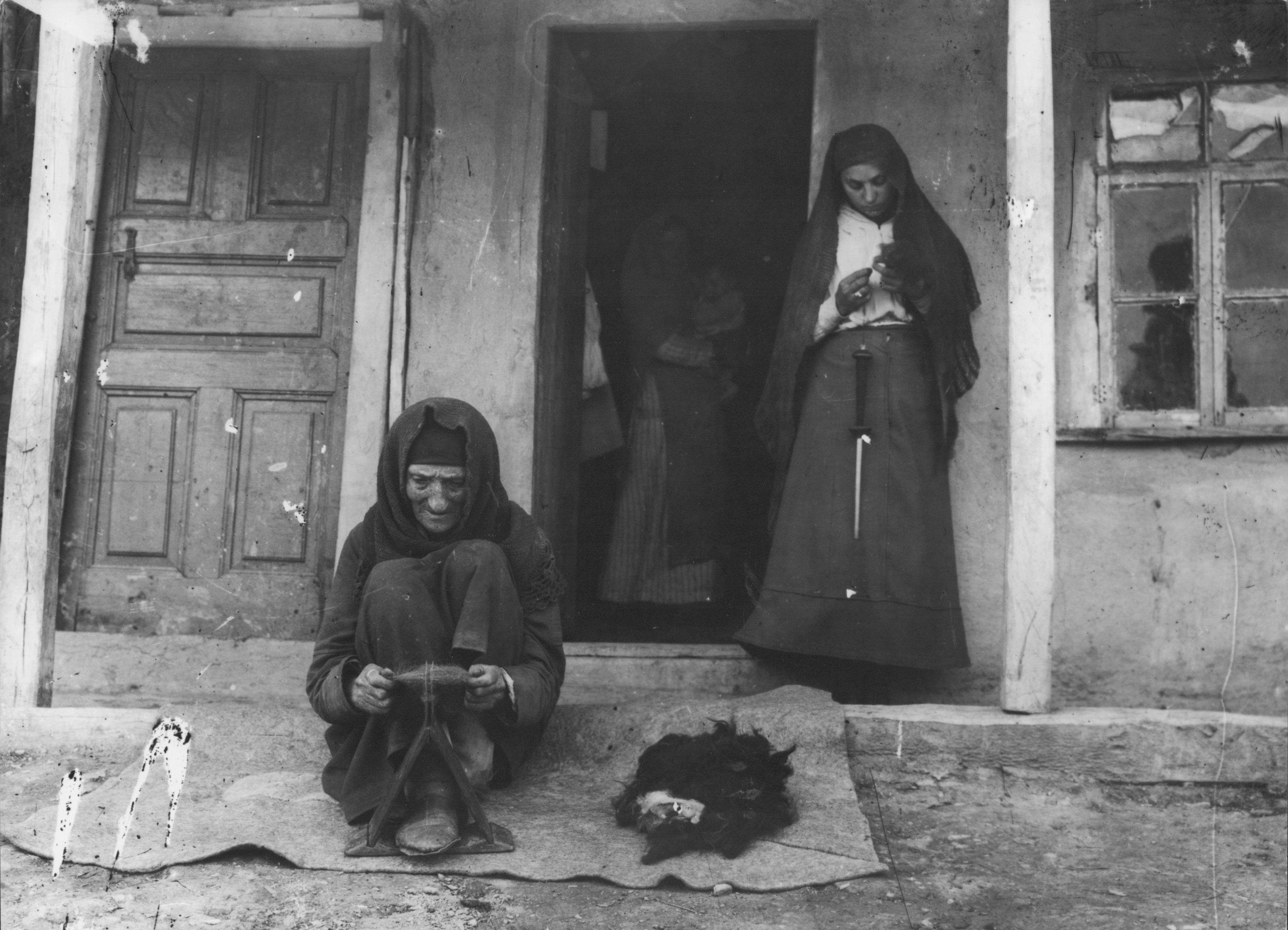

The art of felting carpets—for warming stone homes, for decoration and for cultural expression—has for centuries been a pursuit of women and girls in Ingushetiya, one of Russia’s smallest and southernmost republics. Folk music, paintings, and old photographs have immortalized the wisdom woven into these rugs (called istings in Ingush), which are traditional throughout the Caucasus and Central Asia.

But in Ingushetiya, the labor-intensive craft had foundered in the decades since Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, claiming collusion with Nazis, ordered the deportation of nearly the entire, predominantly Muslim, populace—along with Chechens and other ethnic minorities of the Soviet Union—during World War II.

Decades later, only the elderly remained to fully remember this traditional craft and its symbols, and many of the most beautiful antique examples had been put to more desperate uses: wedged over doors to prevent drafts, used to bundle up children, or sold for food in that time of cold exile in Central Asia.

“We had already lost so much,” says ethnographer Tanzila Dzaurova of the Ingush Scientific Research Institute of the Humanities, in Magas, the capital. “We had to hurry.”

She and a small group of specialists from what is now the historical and geographical society Dzurdzuki, including historians, ethnographers, photographers, ecologists, and restorers–guided by enthusiasts on Facebook and other contacts—began scouring their mountainous homeland beginning in 2012. They poured through national archives and family histories, and traveled to collect and catalogue ancient Ingush ornaments, or designs, still visible on stone carvings, petroglyphs, gravestones, and isting carpets. Any memories, guidance, and fragments that remained or had made it back to the homeland, even faded fragments, were key to salvaging the meaning and image of an ornament before it was truly lost to time.

But what began as a historical investigation has helped to fuel a booming craft revival, including a new felting workshop and artisan association in the capital that has already trained hundreds of girls and women. Dzaurova, who says her own grandmother “would cry from happiness” if she could see what is happening now, imagines the craft as a thread connecting these new felters to generations of women before them. “It’s as if there is a genetic memory in the hands,” she says.

Threads of memory

Now there are classes in schools, competitions, and the book Ingush National Ornament, which documents over a thousand historical ornaments specific to Ingushetiya. Among these are fertility symbols for newlyweds and labyrinthine designs intended to confuse evil spirits.

Many mythical ornaments predate the region’s conversion to Islam, such as depictions of a tree of life symbolizing portals between worlds. Other centuries-old imagery (the oldest recorded examples are from the 17th century) can include symbols of the sun, triangles, and waves. They can represent complicated messages designed to conjure magic and spiritual protections, or to reflect history and memories. In years of epidemics, crop failures, war, and other disasters, says Dzaurova, “ornaments were always asymmetrical.”

Each carpet not just warms or decorates a home but also tells a story, the designs sometimes particular to one family and passed unchanged through generations of its women. In one Ingush folk song, the lyrics detail how a woman named Pyatimat dreams up an isting that her six daughters help her complete in a field of grass over the span of 12 days.

Today, even without shearing and dying the wool, as previous generations would have done, the process of layering wet wool (ideally the softest, shorn from sheep in autumn), rolling and shrinking it, cutting and sewing in designs, and trimming the edges is still labor-intensive, resulting in rough hands and raw elbows.

“Wool is a glorious material and pleasant to work with,” says young Ingush felter Khava Kodzoeva. “Unless, of course, you overdo it!”

The craft is also a way for women, especially in rural areas, to earn a good income. In centuries past, large carpets were completed by groups of women accompanied at times by musical instruments to keep a light mood and positive energy flowing into the final product.

The workshop in the capital has trained felters as young as 11 to those in their late 60s. Two of the earliest students from when the venue opened in 2019 were Kodzoeva, who was 15 when she started, and Zalina Khamkhoeva, who was 55.

“Unfortunately, I did not grow up when this craft was practiced in every home,” says Kodzoeva, but she says her mother and aunt are beginning to carpet weave. One of her favorite ornaments symbolizes women’s well-being. “This ornament has become a symbol of our isting association, because in our association there are only women and women’s well-being is the most important thing for us.” The root of the word “isting” itself relates to the word “woman” in Ingush.

Fellow workshop graduate Khamkhoeva remembers seeing women knitting in the subways as a child, but isting wasn’t a tradition in her home either. “Until the ’40s, this craft was practiced in almost every house, including my grandmothers’. But, during the exile and after returning to the homeland, it was lost. In exile, people survived as best they could—even there, our istings helped them. They exchanged these beauties for a piece of bread or a bowl of curdled milk.”

Since attending the workshop, Khamkhoeva has developed into a skilled and productive craftswoman, one who finds it hard to leave the “magic” when she has to abandon her felting for other daily duties. Among the Ingush, she says, the craft is “a purely feminine affair,” and she does not have a daughter. But she has two daughters-in-law who are already felting. “And I hope that future granddaughters, with the permission of the Almighty, will also love this craft.”