On the trail of the elusive pangolin at a South African safari reserve

On a private game reserve in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province, an unlikely creature is making a tentative comeback — and visitors are offered a glimpse into the conservation efforts to save it and other native wildlife.

Consider for one moment the unlikely existence of the pangolin. The world’s only scaly mammal looks like an armadillo but has more in common genetically with a dog. It has no teeth, poor eyesight, and its tongue, attached to a point near its pelvis, is longer than its body. It has four legs but shuffles along on its back two. So peculiar is its appearance, it has not one but two less-than-flattering nicknames: ‘walking pinecone’ and ‘artichoke with a tail’. People of a certain age will note its resemblance to a Clanger.

Appearing 85 million years ago — when the North American continent nudged against Europe, and Antarctica had yet to break from Australia and make its journey south — the first of its kind shared the world with T-Rexes, velociraptors and flying reptiles the size of fighter jets. It had been around for 15 million years when the first primates swung from the trees, and for more than 84 million years before a species resembling modern humankind came along. It survived several ice ages and the asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs.

When it comes to clinging on in the face of adversity, then, the pangolin is the OG. Which is just as well, given the new entry to its biography: it’s the world’s most heavily trafficked animal, with the continued existence of its eight species hanging in the balance.

Working to ensure the mammal gets to amble through another few million years is Phinda Private Game Reserve in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province. Owned by the &Beyond travel company, Phinda (meaning ‘the return’ in Zulu) runs a unique pangolin reintroduction programme, taking animals rescued from poachers across Africa and destined for the black market in Asia. It lifts the veil on the project by allowing small numbers of visitors to join researchers tracking the animals once they’re settled — and I have come with the specific hope of spotting one.

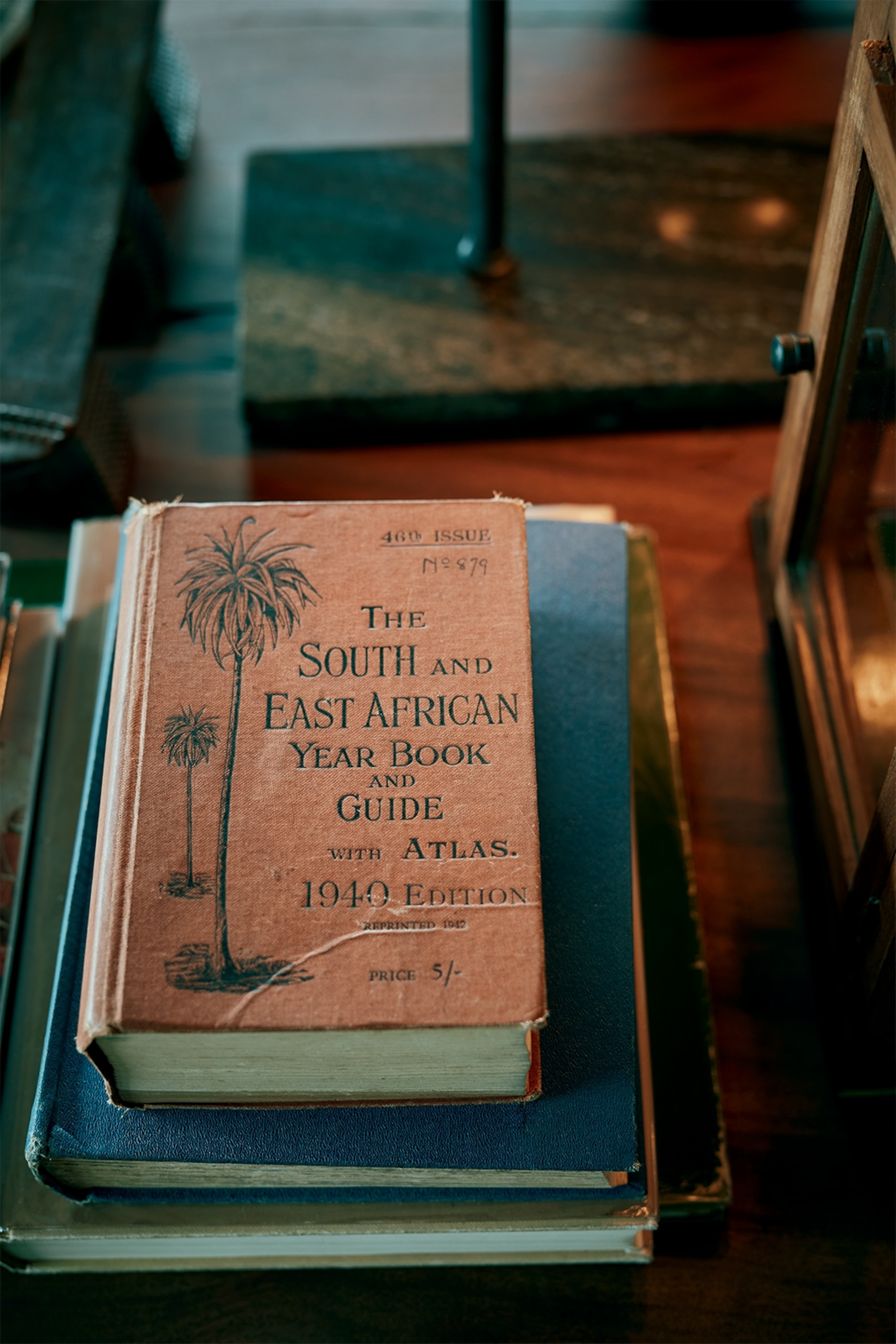

I get my first glimpse rather sooner than anticipated. My base, &Beyond Forest Lodge, is in the north of the 115sq-mile reserve. Its elegant cabins are built around the trees in a thicket of tangled woodland, connected by sandy paths upon which long-lashed nyala antelopes and human guests are constantly surprising one another. A wooden library pavilion sits on a raised platform overlooking grassland where impalas graze in a state of perennial high alert. On a long table in the middle of the room is a collection of paraphernalia that’d be the envy of any zoologist. Among the elephant teeth, porcupine skulls and ammonites is a small brass sculpture of a scaly animal with a long tail and a small head. My first pangolin.

Spotting the real thing is going to require more effort. I meet the reserve’s conservation manager, Dale Wepener, on the deck to learn more about my chances. In beige shorts and shirt, and with the sort of handshake that could break bones, Dale tells me the plan is I’ll explore the reserve by 4WD and he’ll radio in if there are signs of pangolin activity. It’s by no means guaranteed. “The pangolins here are all tagged but that doesn’t make them easy to find,” he says. “If they’re underground, you won’t pick up the signal. And whether they’re above ground depends on the time of year and the weather. They’re very sensitive animals. If they’re uncomfortable, they’ll just leave.”

Thankfully, Phinda is not short of other distractions. As Dale heads back to work, I climb into a Landcruiser behind ranger Clayton Meise and tracker Sabelo Buthelezi and we head out. It’s late afternoon and the forest has taken on a bewitching quality, filled with the sweet fragrance of spiny gardenias, the bubbling calls of kassina frogs and the R2D2-like beeps and trills of eastern nicator birds.

With his wire-framed glasses, safari shorts and desert boots, binoculars or camera always to hand, Clayton looks every inch the boy scout, and he brims with youthful enthusiasm. He has the uncanny ability to tackle a tricky manoeuvre of the 4WD, pick up on the merest hint of wildlife and explain the reserve’s ecosystems all at once, with apparently unwavering focus on each. He’s not long qualified as a ranger, having retrained after the pandemic, ditching his career in events planning. “I’ve always had a love for the bush,” he tells me as we move on. “Now I combine my two loves — wildlife and photography.”

The forest ends abruptly, as though someone has drawn a line and commanded it advance no further, and we bump along into open grassland that stretches to the horizon beneath a heavily clouded sky. Establishing Phinda in 1991 by buying up disparate plots of land, &Beyond has worked with local tribes to manage and extend it ever since. Its aim was to restore an environment depleted by decades of poor farming practice and gradually reintroduce long-gone native wildlife to it. “All this used to be sisal and pineapple farms,” Clayton says, gesturing to the landscape.

We don’t get far before finding a lioness by the track. She observes us with an indifference that borders on disdain, then gets up and walks in front of the vehicle, leading us in a languid procession. “Look, her teats are swollen,” says Clayton. “It means she’s lactating — she probably has cubs nearby.” Rounding a corner, we spot a pride of four lions. The lioness becomes aware of them at the exact moment they become aware of her, and they stand statue-still, staring. “Oh, there might be conflict now,” whispers Clayton.

The lioness turns and runs, and the spell is broken. The group lollops after her, a menacing gang of heavies come to turf a rival off their patch. They disappear into the undergrowth, their rumbling bellows a hint of the drama occurring within. We turn off the track to follow, and instantly come across a leopard draped across the branch of a marula tree. “Everything’s happening!” says Clayton laughing. “I wonder what she thought when all those lions came running past

We find the pursuers lying down the road, panting heavily as dung beetles fizz overhead. “It looks like the lioness got away,” says Clayton, with some relief. “It would’ve been the end of her and her cubs if they’d caught her. She’ll almost certainly move her den now.”

Leaving them to recover, we trundle back as night falls. Out of the gloom, shapes appear like ghosts — a lone elephant in the grass, a white rhino and her calf, a herd of softly grunting buffalo. An unseen foam-nest tree frog squeaks like a malfunctioning robot as fireflies dance in the dark and lightning flashes across the sky. Clayton lets out a contented sigh. “This is going in the books as one memorable drive.”

Booty call

The first drive certainly set a high bar, but one that the reserve seems happy to meet every time we venture out. The sun has barely inched above the horizon the following morning before we’ve encountered two lions mating in the dawn light, tiny red firefinches darting overhead, and met a pair of white rhinos wallowing in a muddy pool, a hippo honking away somewhere in the distance.

By 8am, with the heat already making life uncomfortable, most sensible wildlife has found a shady spot to rest in. We follow their example and retreat to Phinda’s most unique habitat — the sand forest. Created millennia ago, when sinking sea levels left a landscape of sand dunes with just enough moisture to sustain plant life, there are only a few pockets of this ancient landscape remaining in Africa, a quarter of it found in Phinda.

We wander through a patch of woodland as Clayton points out the tiniest evidence of life — bite marks left by a porcupine in a torchwood tree; the roots of an epiphytic orchid dangling from the branches of a 1,500-year-old lebombo wattle. Fawn-coloured nyala jump silently away as we step over fallen trees in a riot of crashing and cracking. Our contribution to the sounds of the forest is rather less melodic than the calls of brown-hooded kingfishers, emerald cuckoos and African paradise flycatchers that surround us.

Perhaps our time in this old landscape has worked some magic, however. When we return to the Landcruiser, Dale calls on the radio to tell us his researcher is hopeful that one or two pangolins may be active later that afternoon. We slowly make our way to the southern part of the reserve to meet them. The plains and forests of the north are replaced by undulating hills swathed in tall grass and pockmarked with boulders, mountains rising beyond.

We meet Dale and researcher Jessie Berndt near the reserve’s airstrip, a short stretch of tarmac embellished by a herd of zebras, a single rhino and a family of warthogs, who stop grazing to watch us pass. Jessie, a PhD student from the University of Pretoria who’s responsible for monitoring and collecting data on the reserve’s pangolins, has a telemetry aerial in one hand, used to pick up signals emitted from the animals’ tracking devices.

“The pangolin we’re going to try and see is called Booty,” Jessie says as we set off in the 4WD. “She came as a sub adult and has had a pup since, but we can’t tell if she was pregnant when she arrived. Of all the pangolin species, we know most about the Temminck’s ground pangolin that we have here in Phinda, but we don’t know the gestation period, how often they mate or when the pups leave.”

It soon becomes clear how little is known about pangolins full stop — it is an animal that guards its privacy with some skill. “We can’t see any pattern why and when this pangolin comes out of the burrow,” Jessie continues, leaning out of the vehicle and holding the aerial aloft. “When she’s out, there’s no pattern to her behaviour either. It’s kind of crazy.”

A series of clicks comes from the antenna, so subtle I struggle to hear it. “It means we’re within a kilometre,” says Jessie, listening intently. We drive on, excitement rising, and then the clicking stops. “She’s behind us now, turn the jeep around.” Driving back 50 metres, we get out and continue through the bush on foot and in silence. There’s a sense of urgency but my progress is clumsy, thorns spearing my face and hands as we squeeze through gaps in the dense undergrowth. We head in one direction, stop, raise the machine, and then try another, moving off in single file.

And then, there she is: a low, shuffling shape with a long tail, a tiny head and shiny scales. Booty waddles through a clearing on her back legs, front paws in the air, bumbling along like a benevolent forest troll. She pauses every so often but seems unperturbed by our presence. “We don’t think pangolins have great eyesight,” Jessie whispers as we crouch down and let her pass. “They have sensitive pads on their feet that pick up vibrations instead.”

We follow Booty at a distance for a short while and then leave her to her day. Interaction is kept to levels that work for the pangolins — the research team is careful not to stress the animals or reveal too much to visitors by allowing them to follow them to their burrows. When we emerge onto the road, it’s with a sense of exhilaration at having met one of the world’s oldest species, and with a forest’s worth of thorns embedded in our clothes.

Around the horn

If I imagined the rest of my time might be anticlimactic after the pangolin encounter, Phinda is quick to brush my concerns to one side. It launched its pangolin programme off the back of other wildlife reintroductions, most notably rhinos. The rhinoceros and the pangolin may seem like unlikely bedfellows but everything Phinda’s team learnt about rhino conservation — from deploying anti-poaching units to involving local communities as ears and eyes on the ground — it uses in its pangolin conservation, too.

We’ve caught glimpses of both white and black rhinos, but they’re elusive creatures, quick to scare — as the photos on my phone of fast-retreating rhino bottoms can attest. For my final days in Phinda, I move to the south of the reserve and my guides there, Declan Porter and Menzi Dlamini, think they can do better.

I meet them on the terrace of &Beyond Mountain Lodge. Sitting on a granite outcrop, the lodge and its stone cottages look over the forested foothills of the Lebombo Mountains. “You can see from here how different the south is,” says Declan. “In the north you have to climb a termite mound to get any height.”

We are soon out in those foothills, Menzi perched on a seat fixed to the bonnet, minutely assessing the landscape, Declan behind the wheel. “I absolutely love looking for rhino,” he says. “One, it takes you to beautiful parts of the reserve and, two, they’re so hard to find.” A keen birder who’s travelled across southern Africa in a bid to spot rare species, Declan is clearly someone who likes a challenge.

On the trail of two white rhinos we’d spotted in the distance, we come across a cheetah and her scrap of a cub lying in long grass. “The cheetahs have been our biggest conservation effort,” Declan whispers as we stop to watch the mother groom her son, their purring audible from the vehicle. The reserve actively manages its animal populations, exchanging individuals with other parks to keep the gene pool healthy — 10% of the cheetah population in South Africa can be traced back to Phinda because of it. “We’re really a conservation project,” says Declan, “but we offer game driving, too.”

Rhinos are a different challenge: teams of poachers hired by organised crime syndicates have almost wiped them out in southern Africa in the past 15 years. As well as deploying armed patrols, Phinda’s solution is to take away the very thing the syndicates prize: the horns.

I see the effect for myself the following day when we track a group of four white rhinos, their horns rounded stubs on their noses. “We dehorn them every 18 months to two years,” Declan explains as the animals move around the vehicle to get a closer look at us, their curiosity getting the better of their nerves. “They’re tranquillised from a helicopter and the horn is then smoothed over using an angle grinder. It’s a huge project.”

It’s also a successful one, with the animals suffering no apparent disadvantage by being hornless. Phinda doesn’t reveal how many rhinos it has, but numbers are up. We see several more over our time there — two black rhinos standing in a pool, so caked in mud there’s not a patch of their hide visible; a white rhino that turns tail and flees with surprising grace and speed as we approach; a black rhino mother and a tiny male drinking at a watering hole, the baby so young he’s barely mastered the use of his legs.

The most majestic sight is one we catch only fleetingly: running along a far hillside, a white rhino bearing two very long, very sharp horns. “There’s a female who lives on this mountain who has a habit of disappearing whenever it comes to dehorning,” says Declan, following her progress through his binoculars. “I guess she might be the one who got away.”

When I put down my own binoculars, the rhino is a tiny speck that’s soon lost from sight. But, as with Booty the pangolin, the encounter is enough. It’s enough to know that, thanks to Phinda, rhinos still trot through these hills and pangolins still wobble through the bush. It’s enough to give hope that they’ll still exist long after we’ve all gone.

How to do it

How to get there & around

The nearest airport is Durban, a four-hour transfer away. There are no direct flights from the UK, so the best bet is to travel via Johannesburg.

Average flight time: 11h.

FlySafair and others fly several times daily from Johannesburg to Durban, with a journey time of just over an hour.

If flight connections necessitate a night in Joburg, stay at comfortable and quiet City Lodge Hotel OR Tambo within the airport. From R2,230 (£100).

When to go

There’s no bad time for safari but the dry months of May to September are particularly good, with sparse vegetation providing excellent visibility and animals gathering around remaining water sources. Temperatures are in the mid to high 20Cs. December to February are wet, humid and hot, around the 30Cs.

More info

andbeyond.com

zulu.org.za

This story was created with the support of andBeyond and cazenove+loyd.

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).