You won’t find these Hawaiian hiking trails in a guidebook

From the beach where hula was said to be born to sacred sites where spirits roam, miles of lesser known trails tell the story of Hawai’i.

Hawaiian legend tells the story of the goddess Hi‘iaka, who travels down a dusty trail on the windward coast of the Big Island of Hawai‘i to a beach where she meets her sisters, including Pele, the volcano deity.

And there, on this remote beach in Puna, Hi‘iaka danced what some consider the first hula.

The path to Hā‘ena Beach, also called Shipman Beach, is still intact. Sometimes muddy and slippery, the 2.9-mile trail deposits visitors at an uncrowded shore known for its fine sands amid an otherwise rugged and rocky coast.

During ancient times, this was one of many footpaths (ala hele) across the Hawaiian Islands that linked coastal fishing villages. In the mid-1800s the trail was straightened and widened to accommodate horses and wheeled carts.

Eventually, as people moved inland, these seaside settlements were abandoned and the trail neglected. Today few people who venture along the Puna Trail to get to Hā‘ena’s white sands know about its cultural importance. “It doesn’t seem like much,” says Jackson Bauer, who works for Nā Ala Hele Trail and Access Program, which manages public resources related to trail maintenance. “But imagine: Hi‘iaka walked on that trail.”

History of Hawai‘i’s trails

One of the last pieces of legislation approved by Queen Lili‘uokalani, before the controversial overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, was the Highways Act of 1892. It states that any trail or road then in existence in Hawai‘i belongs to the government, even on privately owned land. This further implies that these trails—which were used by ancient Hawaiians to gather food, wage battle, get to places of worship, and more—are for public use, accessible to all.

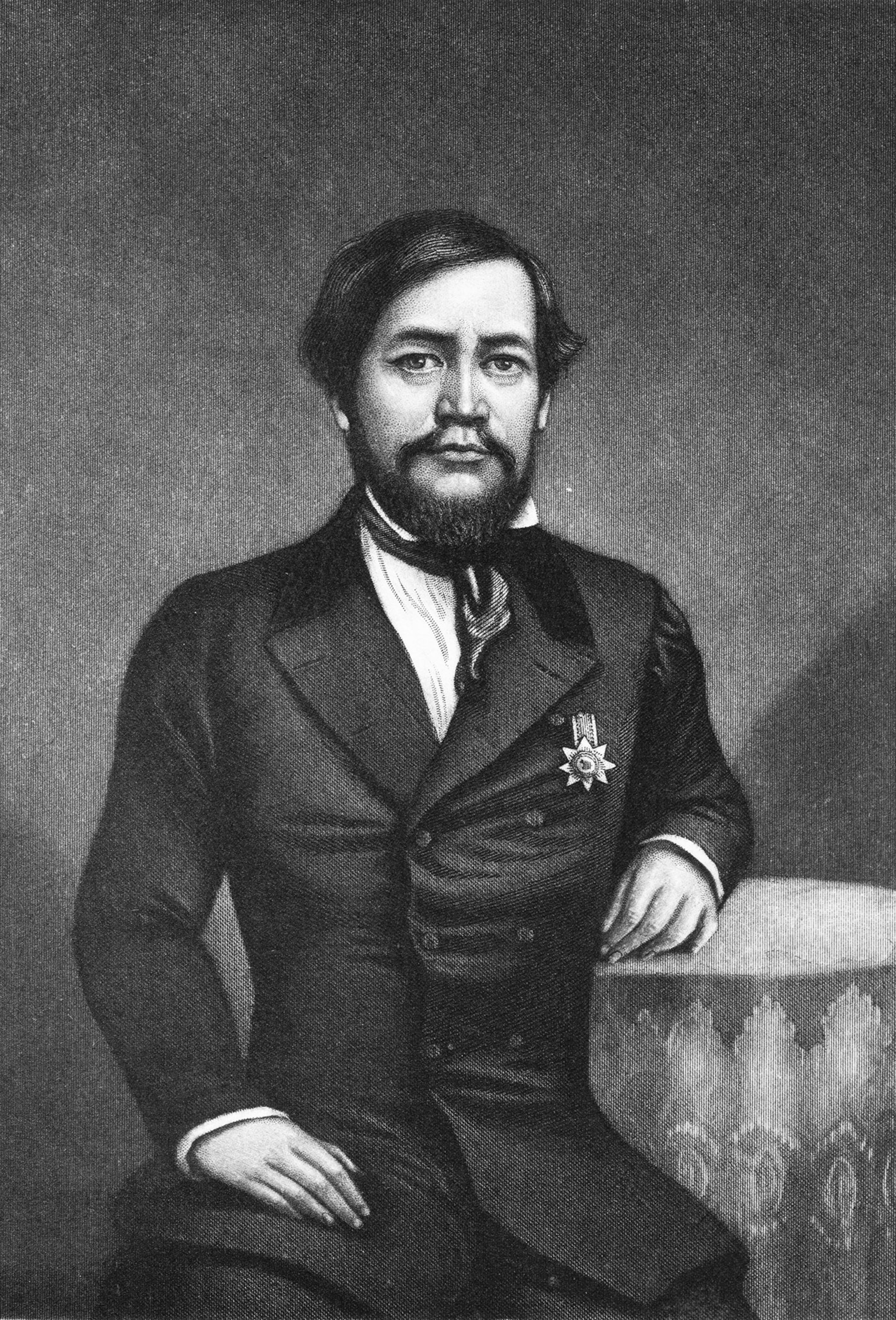

This law came at a critical time for establishing Native Hawaiian land rights. In 1848 the Great Māhele, proposed by King Kamehameha III, redistributed about four million acres of land, abolishing the feudal system and leading to private landownership. Passed before Hawai‘i became a United States territory and state, it ensured that the public—and most importantly, Native Hawaiians—could continue to visit cultural sites.

Thanks to the queen’s foresight, the state now manages hundreds of miles of public trails that lead to heritage areas and native forests or follow meandering streams or tree-lined ridges. While many are now roads and highways—bustling Ala Moana Boulevard on O‘ahu, for example, was a centuries-old footpath that ran along the southern coastline—others are forgotten trails you won’t find in hiking guidebooks. They’re often less popular than the more modern summit or ridge hikes with sweeping views and parking lots. But that’s part of their appeal.

(Explore 3,000-year-old hiking trails on this remarkable Greek island.)

Identifying these footpaths and roads is an element of the Nā Ala Hele program’s job. Staff pore over hand-drawn maps from the 1800s to find evidence of old trails in order to preserve them.

Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail (separately managed, partly by the National Park Service) is a 175-mile network that links communities, temples, fishing areas, and other sites on Hawai‘i. Some parts of the network are thought to have served ali‘i (Hawaiian royalty); other sections were for messengers, who found walking quicker than sailing around parts of the island.

Another trail story tells of a swift runner who departed a village on the island’s northwestern tip for Hilo and returned—about 80 miles each way through the interior of the island—to bring the king a fish from his fishpond; the fish was still alive.

“A lot of these ancient trails have been in use for more than a thousand years—and people still use them. That’s the really exciting part,” Bauer says. He points to major roadways on the islands, from the shop-lined Ali‘i Drive in Kailua-Kona on Hawai‘i to Pali Highway on O‘ahu, which connects Honolulu with the island’s windward side.

“There’s so much history along these trails, and we want to keep them alive.”

Walking the path of spirits

When my six-year-old son and I hike along the wild coastline in Ka‘ena Point State Park on O‘ahu, we walk in the footsteps of ancient Hawaiians. The 3.5-mile trail to the point meanders through one of the last intact coastal dune ecosystems in the main Hawaiian Islands.

About 2,000 seabirds, including the Laysan albatross and the wedge-tailed shear-water, use Ka‘ena Point as their breeding grounds. The area is also home to native wildlife, such as the great frigatebird, the red-tailed tropic bird, and the critically endangered Hawaiian monk seals.

(This bird survived Maui’s fires—but it could soon vanish.)

The path before us is lined with native coastal plants like beach naupaka, a shrub with small white flowers; ‘ilima, an indigenous ground cover with yellow flowers often strung in leis; and naio, or false sandalwood. We might pass a family fishing in a moi hole, a gap in the rocky shoreline where moi, or Pacific threadfin, can be found. Across the islands, moi—known for its slightly sweet taste and firm texture—was a fish often reserved for royalty.

I point out to my son places along the coast where his grandparents—my parents, who are at least third-generation kama‘āina (Hawai‘i-born)—would fish for papio (trevally) and even moi. (Restrictions on the fish were eventually lifted.)

The point itself is known as leina-a-ka‘uhane, a leaping place of souls, where the spirits of the recently dead could be reunited with their ancestors. Here, the leaping place is a large, sloping rock facing the ocean.

“It’s still there. You can still see it,” says La‘akea Perry, a kumu hula—master teacher of hula—who takes guests of the Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu at Ko Olina on guided tours along the trail to Ka‘ena Point. “When you walk there, it’s like going to somebody’s grave almost. You walk that path knowing that it’s the same path spirits travel to get to their final point.”

“People lived and died along these trails. They grew crops and accessed the ocean. They did everything here,” says Bauer. “If there’s a trail, then there’s a lot more things nearby that need to be preserved. The trails provide the clues.”

Where to hike Hawaiian heritage trails

Sprawling over 4,345 acres in West Kaua‘i, Kōke‘e State Park has roughly 45 miles of hiking trails. Most notable is the seven-mile (round-trip) Alaka‘i Swamp Trail, which follows the rim of Kalalau Valley into a rare montane bog environment some 4,000 feet above sea level. Along the way are native plants and trees, home to endemic birds, including the ‘elepaio (monarch flycatcher) and ‘anianiau, a Hawaiian honeycreeper only found here. Hawai‘i’s Queen Emma visited the swamp on horseback in 1870. The setting so entranced her that she had her hundred dancers and musicians who traveled with her perform here before continuing their journey.

2. Moanalua Valley, O‘ahu

This hike can be as short or as long as you want, from a leisurely hour-long stroll along an old valley road to a grueling 11-mile trek to the summit of the Ko‘olau Mountains. The first part—a cobbled carriage road—follows a stream and has interpretive markers. The road continues to Pōhakukaluahine, a sacred boulder covered with petroglyphs.

3. Hoapili Trail, Maui

Part of this 12.5-mile trail follows an old footpath from Keone‘ō‘io Bay. Along the way you pass a native wiliwili (Hawaiian coral tree) and the last lava flow from Haleakalā volcano.

4. Hāna-Wai‘anapanapa Coast Trail, Maui

The 4.6-mile round-trip hike follows an ancient trail along the Hāna coastline in eastern Maui and is composed of rough aa lava. It’s not as popular as nearby Pīpīwai Trail, but it takes in sea arches, tide pools, a blowhole, and a heiau—a religious site—before ending at rocky Ka‘inalimu Bay.

5. Pololū Trail, Hawai‘i

This 1.2-mile out-and-back path takes hikers from the lookout down into the Pololū Valley, an elevation change of 878 feet over the course of the trail. King Kamehameha I was born nearby in North Kohala.

A version of this story appears in the January 2024 issue of National Geographic magazine.