Monarch Butterfly's Genes Reveal the Key to Its Long-Distance Migration

A gene for efficient muscles allowed the insect to fly farther, new research suggests.

Monarch butterflies owe their long-distance migrations to one gene honed for efficient flight, according to a study released Wednesday. (Related: "Monarch Butterflies Struggle.")

The study of monarch genes also suggests that the butterflies began their evolutionary history as a migratory species that spread worldwide before a few groups settled down and eventually became separate homebody species.

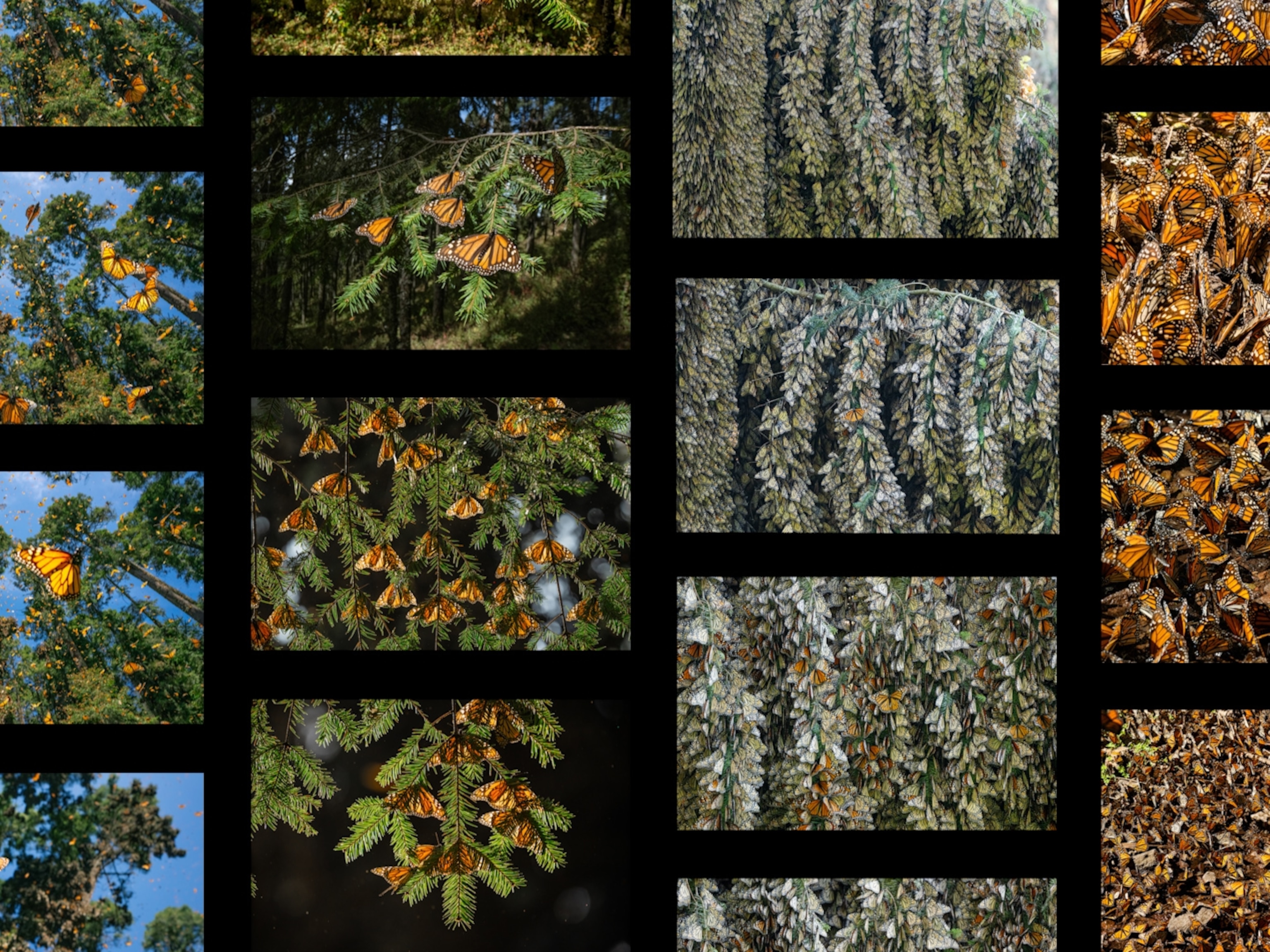

In an epic migration, the monarch butterfly travels in great masses from Mexico to Manitoba every year. The range of that journey has stretched farther and farther north since the end of the last ice age, thanks to a gene that makes butterfly muscles more efficient, researchers suggest in a study published in the journal Nature.

"At first we thought migratory butterflies needed to bulk up with big muscles," says study senior author Marcus Kronforst of the University of Chicago. "What emerged is that natural selection is mighty powerful for flight efficiency." (Video: "Monarch Butterflies.")

The study also revealed that a single gene plays a big role in monarchs' signature orange-and-black coloration, and a flip of this genetic switch is responsible for the unusual white monarch butterflies of Oahu.

In the backdrop to the study, the iconic butterfly's numbers have been dropping precipitously, down to 33 million in 2013, a decline tied to a drop in the milkweed they depend on. (Related: "Monarch Butterfly's Reign Threatened by Milkweed Decline.")

Monarch Muscles

Millions of migratory monarchs travel north from Mexico in March, then head south in October, with four generations of the insects living and dying along the way. The insects have to make decisions about starting and stopping migration, so the study team expected genes related to behavior that would separate migratory monarchs from others.

Kronforst and colleagues compared the full genetic blueprints, or genomes, of 89 monarch butterflies, Danaus plexippus, and nine others from four nonmigratory families related to them, most notably South America's southern monarch butterfly.

"To our surprise one gene really leaped out of the analysis, and it wasn't involved with behavior," Kronforst says. Instead, the gene helps with the formation of collagen, the stretchy stuff in connective tissues. The collagen gene appears to dial down energy expenditure in the muscles of long-distance travelers.

The team also tested butterflies' flying abilities in test chambers (two-liter bottles shaken for ten minutes to spur flying), and respiration sensors found that migratory monarchs flew most efficiently, but not most powerfully.

Migrating butterflies are essentially endurance athletes, while others are sprinters, Kronforst suggests. The sprinters may need to out-compete other bugs for food, he suggests, while migratory ones fly to places where they face less competition.

Muscle efficiency would be crucial for that lifestyle. "If you can't make it back to Mexico, you're dead," says evolutionary biologist and monarch expert Andrew Brower of Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro.

Migratory Monarchs

How and when did monarchs start migrating? The study suggests that migration was a founding condition for the species, which descended from a split with an ancestral African species more than a million years ago.

Monarchs probably started out in Mexico, after their migratory ancestors crossed the Atlantic, says ecologist Richard ffrench-Constant of the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom. "Who else is going to survive a long trip?" he asks.

The study authors speculate that monarch butterflies gradually began flying farther and farther north each spring during the last 20,000 years, as an ice age ended in North America, now traveling some 3,000 miles (4,828 kilometers) on their trip.

Multiple ice ages have occurred since monarch butterflies split from their closest relatives, though, so Brower says he doubts that the most recent one alone so effectively shaped their behavior.

Color Cues

Another key feature of monarchs—their color—also ties back to a single gene, the study suggests. A few monarchs are white, including Hawaii's "niveous" butterflies found on Oahu. That white tint seems to come from one other gene, which seems to drive the change in color, the team found.

The same gene leads to dull brown coats in a family of black mice. The find is a first linking color in mammals to that of invertebrates, says ffrench-Constant.

"The role of single genes in sometimes having an outsized effect on species is sort of the theme of these results," he says.

Follow Dan Vergano on Twitter.