Migratory monarch numbers take a dive—but they’ll bounce back

Warm temperatures and drought have likely contributed to fewer butterflies in their wintering grounds of Mexico, but experts say the subspecies is resilient.

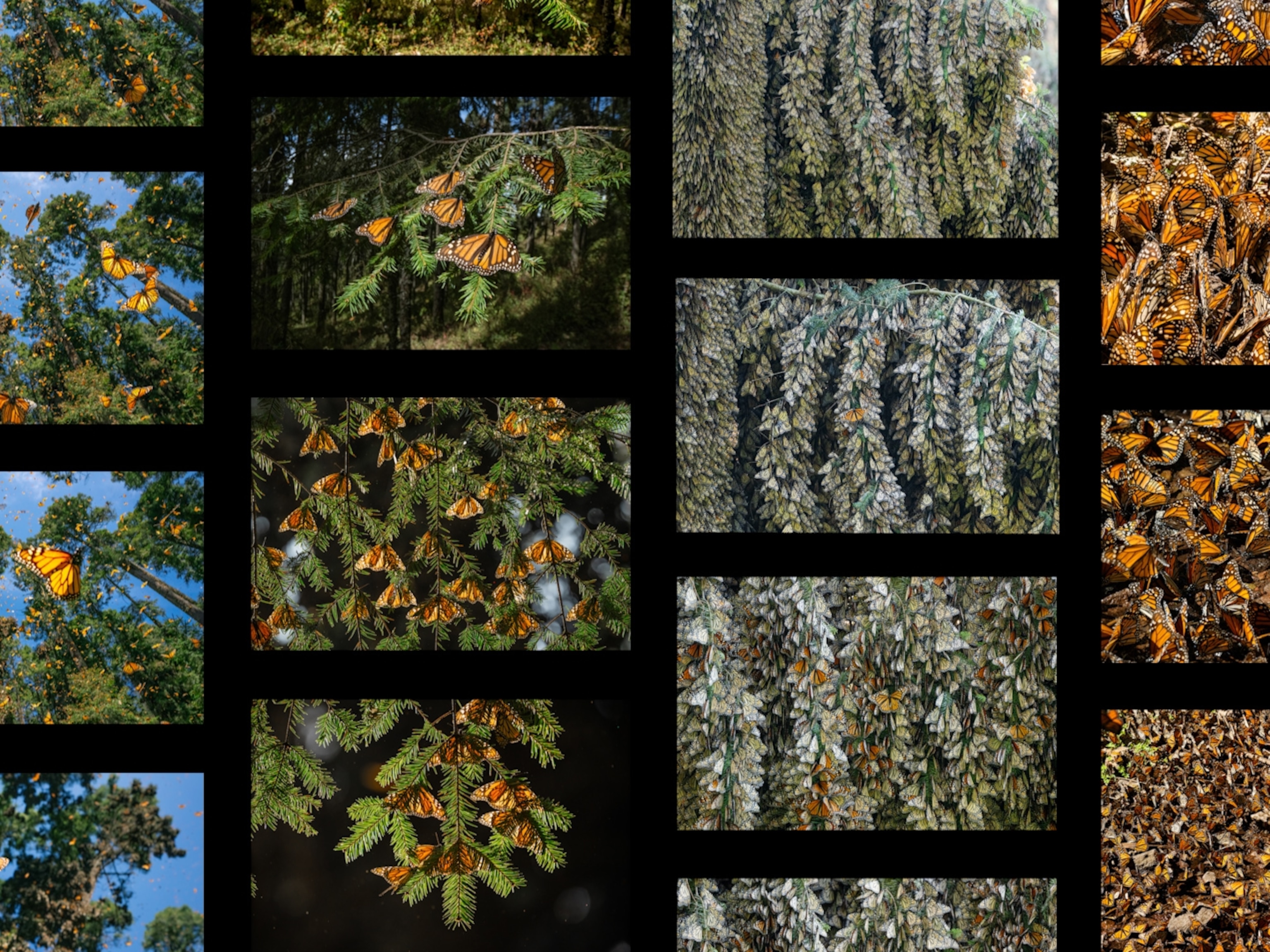

Each year, millions of migratory eastern monarch butterflies travel up to 3,000 miles from southern Canada and the Great Plains of the United States to spend their winters in Mexico’s mountain forests.

But about 59 percent fewer of the insect made the trip this winter compared with the last, according to a new report released this week by the Mexican government and other groups. The new data reflects a troubling trend for the species as it faces the joint threats of climate change and habitat loss throughout its range.

The migrating population, a subspecies, represents about 85 percent of all eastern monarchs, according to Jorge Rickards, director of WWF-Mexico. This data, he said, is a good indication of the health of the eastern monarch as a whole. (Read: "Can monarchs adapt to a rapidly changing world?")

"It is a very direct call to attention that nature has given us that we cannot lower our guard, and we need to continue strengthening conservation measures," Rickards says.

Migratory monarch butterflies were present in 2.2 acres of Mexican forest in the second half of December 2023, compared with 5.5 acres in the same period in 2022, according to the report by WWF, the National Commission of Protected Natural Areas in Mexico, and the WWF-TELMEX Telcel Foundation Alliance. Overall, scientists surveyed nine butterfly colonies in two states—four in Michoacán and five in Mexico.

The acreage is the second-smallest number since 1993, when data was first recorded. The lowest-ever recording was in 2013 to 14, when monarch butterflies occupied 1.7 acres; the highest was 45 acres, in 1996-97. (Related: “Monarch butterflies migrate 3,000 miles—here's how.”)

It is normal for monarch populations to fluctuate over time, Rickards says.

In 2022, the International Union for Conservation of Nature declared the migratory monarch butterfly endangered, a decision that made headlines around the world. In October 2023, the organization downlisted the subspecies as vulnerable to extinction, claiming that models showing the insect’s demise were likely too cautious.

That said, in the case of eastern monarchs, "the overall trend has been to decrease, so we need to act very quickly and very strongly to build conditions for them to bounce back," says Rickards, for instance by reducing pesticide use in Mexico.

“It needs us humans”

When monarch eggs hatch into caterpillars, they feed on milkweed, the only plant on which migrating monarchs lay their eggs. This makes them toxic to their predators. If they're born in the late summer or early fall, the butterflies will then make the trip south to Mexico for the winter, where they gather in the millions on native fir trees.

It's a trip that millions will take but from which none will return. In the spring, the population starts to move back north, laying eggs along the way and creating a new generation to carry on the relay back to the United States and Canada. The journey can take four or five generations in total to complete. Incredibly, monarchs on their way north have life spans of five to seven weeks, while those headed south can live up to eight months.

Eastern monarch populations have declined by about 80 percent since the 1980s, mostly due to the growth of agriculture, which has killed off vast amounts of milkweed. (Read more: “Monarch butterflies may be doing better than thought, controversial study suggests.”)

High temperatures and drought in the United States and Canada during the winter of 2023 to 2024 are to blame for this year’s decrease, as they can destroy the remaining milkweed.

Deforestation in Mexico has also eliminated areas the butterflies need to survive the winter. Herbicides and pesticides kill milkweed and affecting the butterflies' health, the report said.

The insects’ decline can degrade other parts of the ecosystem, particularly since they’re major pollinators for both U.S. and Mexican food crops.

"The simple act of millions of butterflies migrating through our country and pollinating all these different plants is certainly important," Rickards says. (Related: “The monarch butterfly’s spots may be its superpower.”)

The United States, Canada, and Mexico each have their own plans for protecting monarchs. In Mexico, the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, works to reduce illegal logging and plant pollinator-friendly habitats.

Rickards is hopeful the monarchs will come back. "The population is very resilient," he said. "But it needs us humans.”