Monarch butterflies may be doing better than thought, controversial study suggests

The North American population, which may be listed under the Endangered Species Act, is still plentiful, according to citizen science data.

After sifting through 25 years’ worth of data, a team of scientists have come to a rather surprising conclusion—the monarch butterfly population seems to be increasing.

If true, the findings could rewrite the charismatic insect’s narrative, which has been defined by doom and gloom over the last several decades. To be clear, the monarch butterfly species, Danaus plexippus, overall is still thriving, inhabiting a wide range that includes such diverse places as North Africa and Southeast Asia.

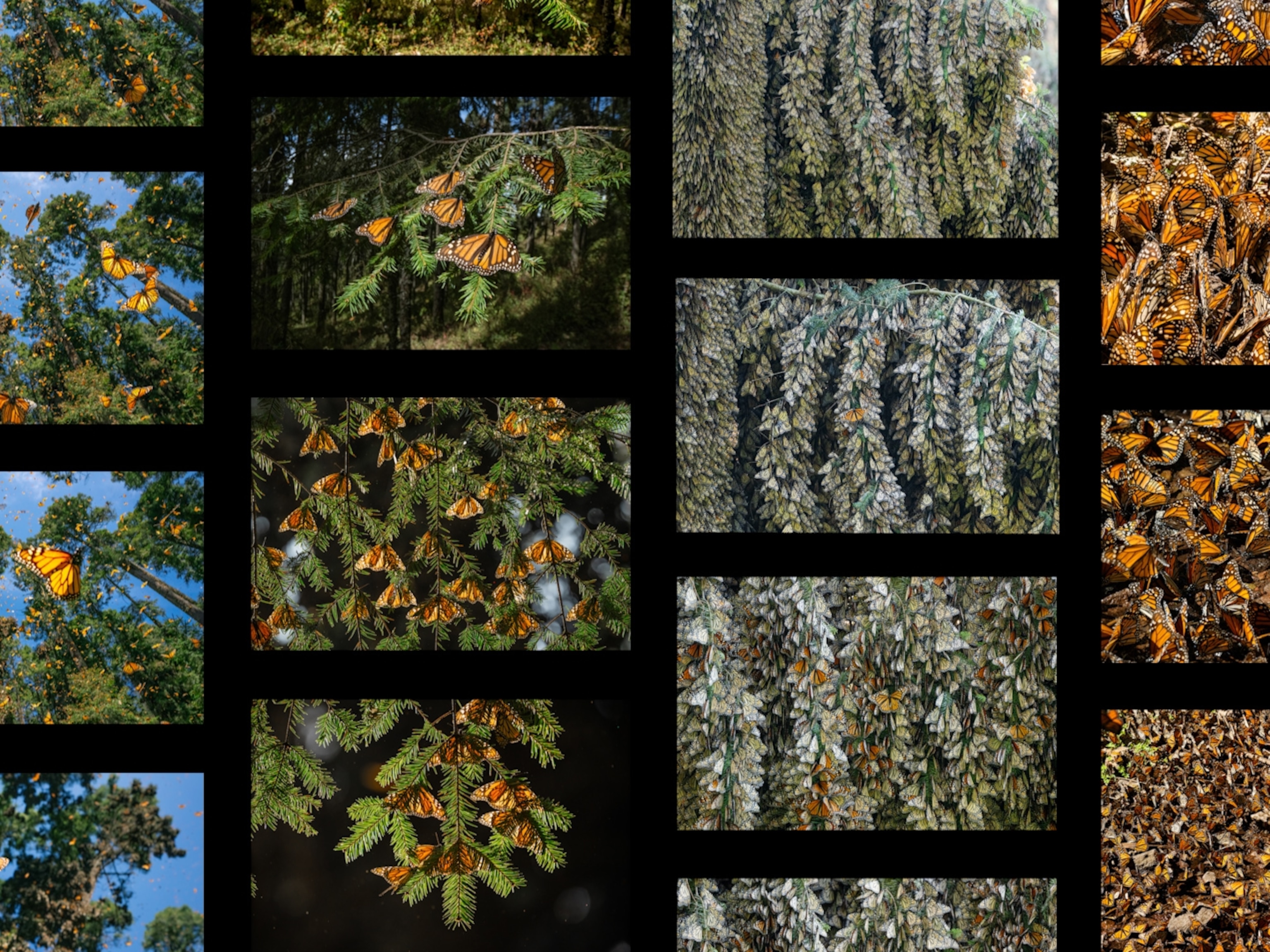

But eastern monarch butterfly populations in North America are different from their kin, because each year they embark on a massive migration from summer grounds in Canada to forests in southwestern Mexico, where they spend the winter. (Read about the discovery of the monarchs' winter home in a 1976 issue of National Geographic magazine.)

In recent years, the wintering population has plummeted, likely a result of pesticide use and the widespread loss of butterfly host plants, known as milkweed, throughout the animal’s summer range in Canada and the U.S.

By some accounts, this eastern population has declined by around 80 percent over the last 40 years. And monarchs on the western side of North America—which also migrate but only go as far as southern California—are purportedly down 99 percent over the same time span.

Based on such data, in December 2020, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced the subspecies of North American monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus plexippus) met the requirements for protections afforded by the Endangered Species Act. Yet due to other, more dire species needs, the agency declined to list the insect, with plans to re-evaluate in 2024. (Read more about why monarch butterflies were denied endangered species protections.)

Now it may not need to, according to authors of a new study, published today in the journal Global Change Biology.

When senior author Andy Davis, an animal ecologist at the University of Georgia, and his co-authors scoured data collected during the North American Butterfly Association’s annual butterfly counts, they found that while the population has fallen in some places, it has also increased in others. And looking at those overall numbers, scientists estimate that the gains compensate for the losses.

Davis and his colleagues aren't the first to make this conclusion based on NABA's data, but theirs is the most comprehensive analysis to date, he says.

The monarch’s complex life cycle makes it particularly difficult to monitor, Davis adds.

In any given year, there are five separate generations of monarchs migrating through North America. That's a major reason why scientists have focused on Mexico’s wintering colonies: It's the only place where the animals gather in one place, making it easier to perform surveys.

But focusing on one piece of the monarch’s life cycle runs the risk of missing the wider picture—which is why Davis and his colleagues turned to citizen data, which they say provides a reliable estimate of the insect's numbers.

“This is a crazy situation where now we’re thinking about listing one of the most abundant butterflies in North America,” says Davis, “because of a perception issue, and not really because of the data.”

Seeking butterflies

Each July, the butterfly association, a nonprofit based in New Jersey, gathers thousands of volunteers to look for monarchs in 15-mile-diameter circles, a methodology that mirrors the Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Counts.

This massive effort ensures data is collected from more than 450 sites across the U.S. and Canada, providing an unparalleled annual snapshot of monarch numbers for scientific research.

Over the past 25 years, the relative abundance of North American monarchs has grown by 1.36 percent per year. What’s more, the authors note, of all the places monitored by NABA, monarchs are seen at more sites than any other butterfly species.

“I like to say that we had the best statisticians in the business working on this project, and they used the most sophisticated, up-to-date analyses possible,” Davis says.

He adds that data at this scale would not be possible based on university or government efforts alone.

“This project is kind of a success story, because we used their data to answer a long-standing question about one of the butterfly species they’ve been tracking.”

‘There’s always uncertainty’

As crucial as the NABA data set is, it’s not perfect.

Kathleen Prudic, a wildlife biologist at the University of Arizona who was not involved in the new study, says that a traditional scientific survey would break a site up into a grid and make sure each section of that grid was sampled equally.

Transects, or walking along a set path, are another way scientists quantify the number of animals in a given area. The NABA counts, on the other hand, aren’t regulated as well, because the volunteers don’t have to walk the same paths each year.

“The paper represents the data, what data we have, and I think it analyzes it well,” says Prudic. “But there’s always uncertainty" in using the citizen science data to draw conclusions about such a complex and wide-ranging species.

Emma Pelton, senior conservation biologist with the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, expressed similar concerns. The Xerces Society is one of the organizations that originally petitioned the Fish and Wildlife Service to list the monarch in 2014.

“We work with a ton of community scientists, and this is another example of the really cool analyses we can do when people go out and look for insects,” says Pelton, who was also not involved in the study. “However, you have to talk about the limitations.” (Learn more about threats to monarchs, such as pesticides.)

Namely, Pelton says that the surveys carry a degree of bias, because they are conducted by people who typically only go out one day a year, in the peak of summer, to sites that are known to be frequented by lots of butterflies. Furthermore, "they are not randomized in space or time, nor representative of the landscape.”

“And that’s really important when we’re trying to think about this migratory insect that can be everywhere, essentially, in the lower 48,” says Pelton. For instance, monarch butterflies also inhabit urban and agricultural areas typically not included in NABA transects.

“Overall, these are well-respected authors, and they took a crack at this really big issue with a really solid data set,” says Pelton. “But I don’t think it’s the right data set to get at the questions they’re trying to answer.”

That's why neither Prudic nor Pelton believe the new study should change the Fish and Wildlife Service’s decision the species is warranted as part of the Endangered Species Act, in part because many populations, like those in western North America, are still experiencing declines.

Matt Forister, an entomologist at the University of Nevada, Reno, says that despite the paper’s findings, “we need to be cautious about drawing conclusions, especially when you know this particular species is in strong declines in other parts of its life cycle.”

“If these declines continue, you could potentially have a situation where all the remaining monarchs are clinging to a single tree in Mexico,” he says. “At that point, all it would take is one storm to knock them out.”

Georgia Parham, spokesperson for the Fish and Wildlife Service, says by email that the monarch will continue to be evaluated for listing status each year, and if it still meets the conditions in 2024, it will join the Endangered Species List.

‘Bambi of the insect world’

The study authors assert the data is solid and speaks for itself.

“The key difference here is that we’ve moved beyond a regional analysis, and we’ve done a continent-wide analysis,” says study leader Michael Crossley, an agricultural entomologist and molecular ecologist at the University of Delaware. “And this is where we start to see maybe a fuller picture of increases alongside decreases.”

Davis adds it’s hard for people to change their perception that monarchs are in trouble, in part because it’s “useful myth” for generating donations to nonprofits.

Meanwhile, of the 456 butterfly species tracked by NABA during the study period, 320 species are dwindling and in greater need of conservation, such as the frosted elfin and Avalon hairstreak. (Read why warmer autumns are harming hundreds of butterfly species.)

“The monarch is the Bambi of the insect world. When people hear that the monarch is in trouble, they open up their purses,” Davis says.