Monarch butterflies aren't endangered, reversing recent decision. Is that good news?

Data showing the migratory monarch's decline were too precautionary, prompting the IUCN to change its status from endangered to vulnerable.

Just last year, the International Union for Conservation of Nature declared the migratory monarch butterfly endangered, a decision that made headlines around the world. On September 27, with little fanfare, the organization downlisted the subspecies as vulnerable to extinction, a level lower on the risk-rating system.

The reason? Models showing the insect’s demise were likely too cautious, and its numbers are falling more slowly than thought, according to the IUCN.

To be clear, most of the large, orange-and-black butterflies known as Danaus plexippus are doing just fine. This is why people in many parts of North America still see the charismatic insects fluttering about their backyards and gardens.

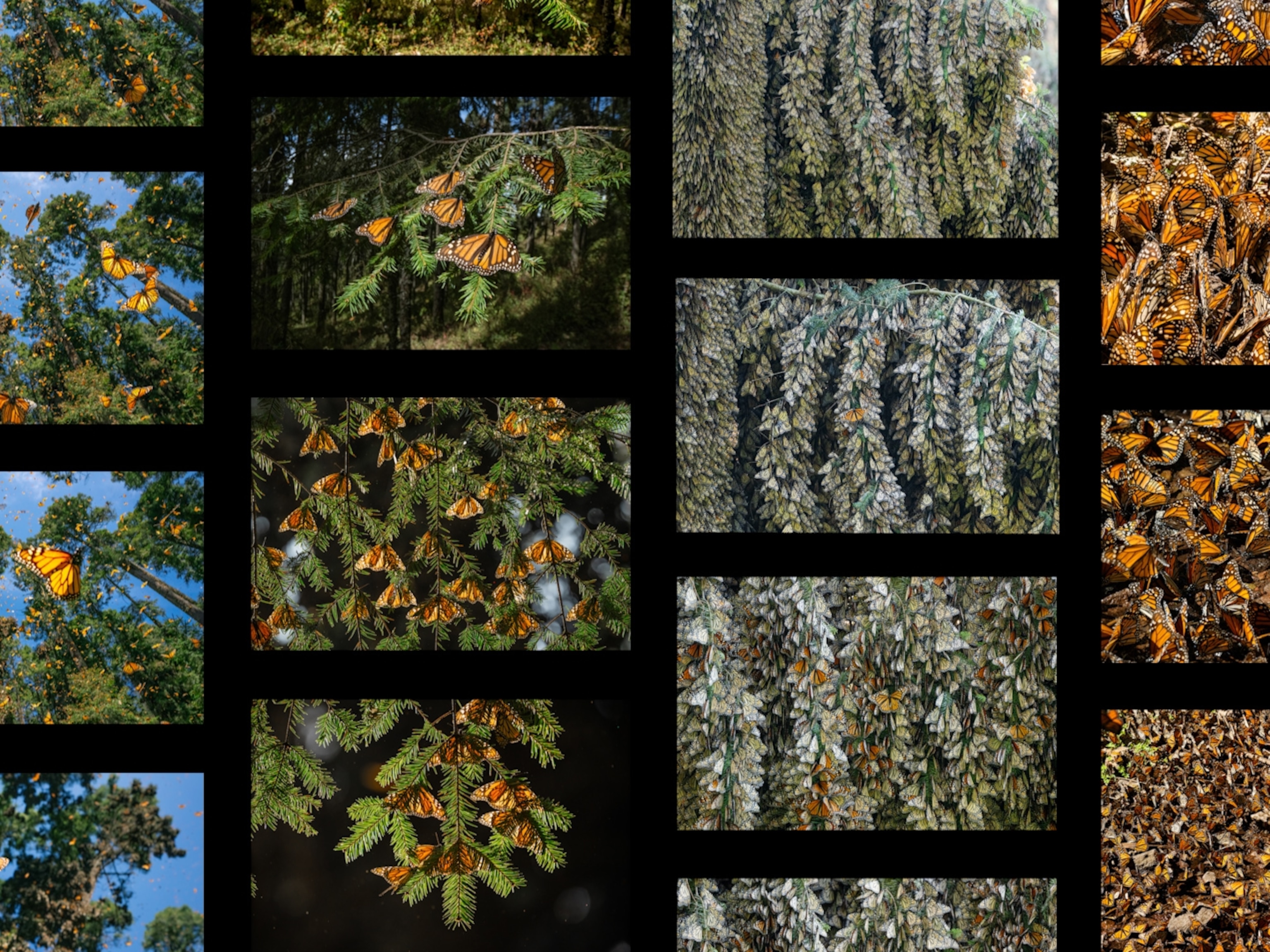

However, in recent decades scientists have become concerned about the migratory monarch, Danaus plexippus ssp. plexippus, a subspecies which undertakes an incredible, 3,000-mile, multi-generational migration each year from breeding grounds in Canada and the United States to wintering grounds in Mexico. (Related: “Monarch butterflies migrate 3,000 miles—here's how”)

According to previous estimates, the eastern population of migratory monarchs has declined by as much as 84 percent between 1996 and 2014. Worse still is the fate of the western migratory monarchs, whose population dropped from around 10 million insects in the 1980s to just 1,914 in 2021—a loss of about 99.9 percent of the population, according to the IUCN.

Threats include loss of breeding habitat, pesticide exposure, and climate change, which may cause temperature swings in the insects’ wintering grounds outside of Mexico City.

Yet other data contradicts such severe declines. When Andy Davis, an animal ecologist at the University of Georgia, and his co-authors scoured data collected during the North American Butterfly Association’s annual citizen science butterfly counts, they found that while the population has fallen in some places, it has also increased in others. And while he takes no issue with the idea that monarch numbers are low at the Mexican wintering grounds, his team’s analysis suggests the subspecies’ relative abundance has actually grown by 1.36 percent each year in their breeding areas. (Read more: “Monarch butterflies may be doing better than thought, controversial study suggests.”)

That’s why Davis led a petition to IUCN to review the endangered status, which prompted the migratory monarch’s new vulnerable listing.

Though status changes are common, they’re usually accompanied by some new data that shows a clear change in a species’ outlook, or new information that’s come to light. In this case, it’s neither.

Instead, the IUCN acknowledged that their models were “too precautionary and less plausible than models that suggest the rate of the decline has changed and is now much slower than it was in years past,” says Anna Walker, who led the IUCN’s initial assessment of migratory monarchs and is also a species survival officer for invertebrate pollinators at the New Mexico BioPark Society.

The decision will be published in the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species update on December 7, 2023.

Too far, or not far enough?

Yet Davis and others think that even a vulnerable listing is too extreme, and that the subspecies should be reclassified as “least concern,” the category of the lowest extinction risk.

“It didn’t go far enough, in my mind,” says Davis.

In his 2022 study, Davis and colleagues’ continent-wide study of migratory monarchs found some regions of the country where there’s been some local declines, some regions where there’s been increases, and regions where there’s been no change.

“But if you add them all up, we found no long-term overall decline in the population during the summer, which tells me that regardless of how many monarchs there are in the winter colonies, they bounce back every spring.” (Learn more about how climate change may impact monarchs.)

Even so, numerous scientists contacted about the 2022 research urged caution about the results. For one, while data sourced from citizen scientists are extremely valuable, the approach is not always consistent.

There’s “always uncertainty" in using citizen science data to draw conclusions about such a complex and wide-ranging species, Kathleen Prudic, a wildlife biologist at the University of Arizona, said at the time.

What’s more, the subspecies’ wintering ground population is more susceptible to a freak event, meaning it may be more important than other groups.

“If these declines continue, you could potentially have a situation where all the remaining monarchs are clinging to a single tree in Mexico,” Matt Forister, an entomologist at the University of Nevada, Reno, told National Geographic in 2022. “At that point, all it would take is one storm to knock them out.”

Though losses at the wintering grounds were clear in the 1980s and 1990s, the numbers have since stabilized, Davis asserts. And this is precisely what the IUCN listings try to characterize—what has happened over the last 10 years or three generations. (Why insects are plummeting—and why it matters.)

“So for over a decade now, the colonies haven’t really changed in size. What that means is they are safe and stable,” says Davis.

Scientific consensus

While the IUCN’s decision carries much weight within the scientific community, the group does not possess any lawmaking power. Ultimately, it remains up to the monarch’s host countries—Canada, the United States, and Mexico—to determine what, if anything, to do with the finding.

For instance, in 2020, the United States decided that the migratory monarchs qualified for legal protections under the Endangered Species Act, but that such a listing was precluded by species deemed to be of higher priority. It plans to revisit the migratory monarch’s status in 2024. (Read more: “Monarch butterflies denied endangered species listing despite shocking decline.”)

“I think, in the end, [the IUCN decision to downlist to vulnerable] wasn’t a major change,” says Emma Pelton, senior conservation biologist with the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, one of the groups which initially petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list the migratory monarch as endangered in 2014.

In fact, Pelton says the IUCN and USFWS’ decisions so far on monarchs suggests a scientific consensus.

“We can argue about exactly how concerned different bodies are at different points in time,” says Pelton, “but I think this is like another vote towards the idea that they are in trouble, and we need to make changes so that the migration continues.”

Monarch mania may have a downside

While Davis disagrees with many about the migratory monarch’s situation, he cares deeply about trying to help the butterflies. In fact, he believes a narrative of victimization is now doing the species harm.

The endangered listing, he says, “led to this growth of a sort of dangerous activity by regular folks, where people heard the monarchs were endangered, and so they kind of took it upon themselves to try to fix that by bringing monarchs into their kitchens.”

For instance, well-meaning people have bought monarch-rearing kits online and even taken monarch butterfly chrysalises out of the wild to rear indoors.

Rather than boosting the population, Davis says such practices can spread parasites to wild monarchs and produce individuals that have lost the ability to properly navigate. (Related: “The monarch butterfly’s spots may be its superpower.”)

“Ironically, I want to help the monarchs,” he says.