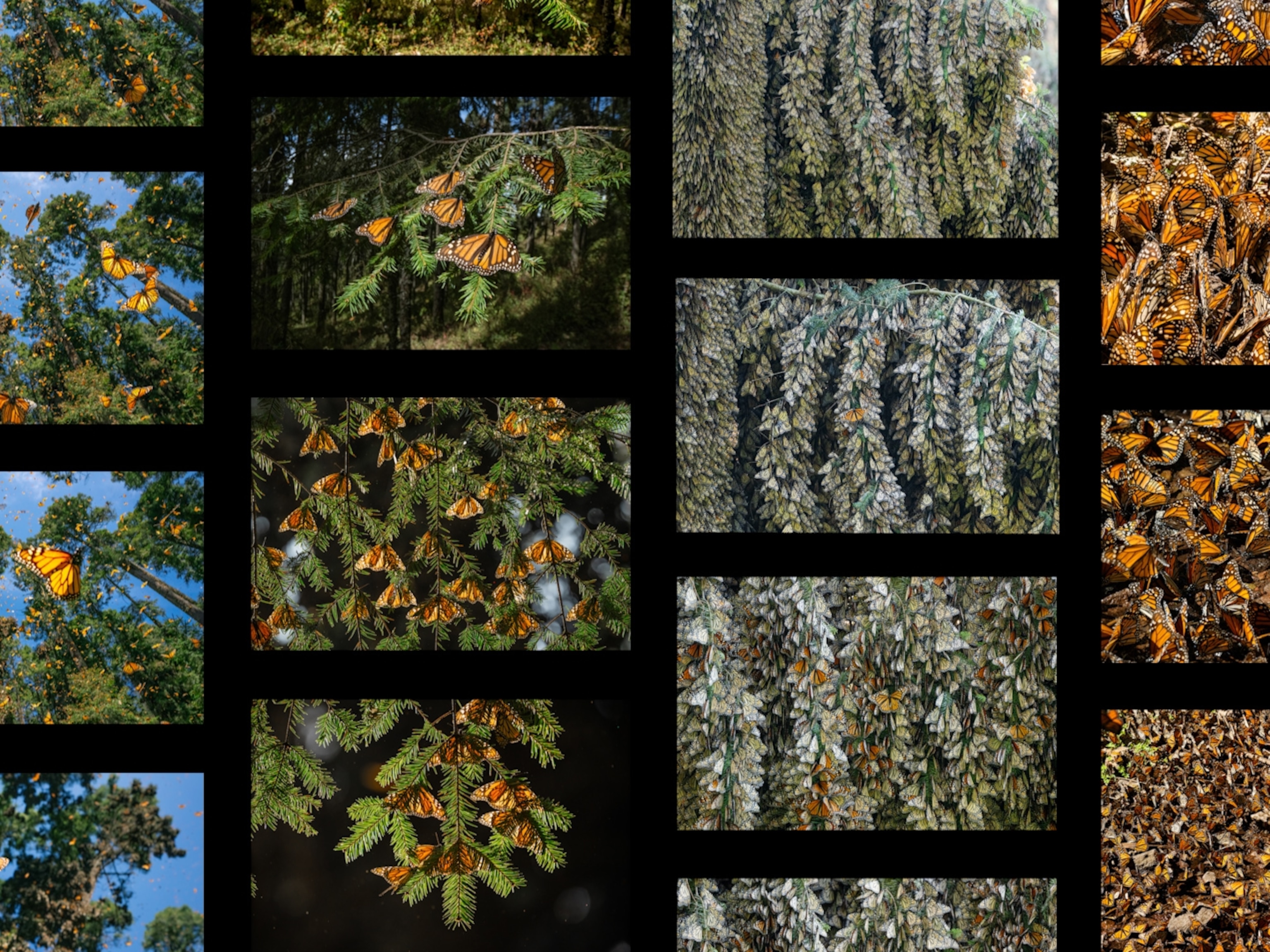

1 in 5 butterflies in the U.S. have disappeared in the last 20 years

Researchers identified over 100 species that have dropped by more than 50 percent in the last two decades: "This is a wake-up call."

In the last 20 years, one in five butterflies have disappeared in the United States.

According to a landmark study published today in the journal Science, total butterfly abundance in the U.S. has declined by 22 percent across all species between 2000 and 2020.

“This is a wake-up call. People should be seeing this number and being very, very concerned, not just about butterflies, but about the state of insects in general,” says Eliza Grames, a conservation biologist at Binghamton University in New York and coauthor of the study.

While insects are notoriously difficult to sample across broad geographic areas, more research has gone into monitoring butterflies than any other insect group. Events like the North American Butterfly Association’s annual Fourth of July butterfly count have also helped bolster these counts.

Across 35 monitoring programs, scientists and volunteers have identified 12.6 million butterflies from 554 species at 2,478 unique locations. And Grames and her colleagues were able to use those data to conduct the most expansive butterfly population analysis ever for the U.S.

Initially, Grames says she expected to see declines for many species, but that once all the data was scaled up to cover the entire nation, she also expected to see enough increases to wash out the bad news. Unfortunately, that was not the case.

“It’s kind of an overwhelming amount of loss and decline,” she says.

Even common species are in trouble

Lest you think the widespread declines are attributable to a handful of little-known species that were already close to extinction, the scientists found that 13 times as many butterfly species were in decline compared to those that were increasing.

Declines were most prominent in the Southwestern region of the U.S., while the Pacific Northwest was declining the least. More than 100 species saw drops greater than 50 percent over the twenty-year timespan. This includes 22 species that have declined more than 90 percent, including the Hermes copper, tailed orange, West Virginia white, California patch, and sandhill skipper.

“While the numbers reported in this paper are sobering, they sadly don’t come as a surprise,” says Monika Böhm, co-chair of International Union for Conservation of Nature’s SSC Butterfly & Moth Specialist Group.

“Wherever butterflies have been monitored, and that’s so far mainly in Europe and North America, declines have been reported, including for some of the commonest and most-loved species,” says Böhm, who was not affiliated with the research.

A bigger biodiversity problem

The reality may be even worse than the story the numbers tell. Even with the vast number of observations included in the study, the scientists only had enough data to conduct species-level analyses for just over half of the butterflies found in the U.S. Huge portions of the Mountain-Prairie region had almost no data at all.

“Which means that the ones that we’re able to do the analyses for are already probably doing better off than the ones that we don’t have data for,” says Grames. “Because they’re more common. We’re able to actually monitor and observe them from year to year.”

This means that for the other half, it’s possible they’ve already slipped below an inflection point where we no longer observe them regularly in monitoring programs, she says.

Of course, butterflies are not the only insects in danger, and their declines connect to bigger concerns. “I think it is broadly indicative of the overall biodiversity crisis,” says Grames.

Mayfly numbers have been cut in half, agricultural fields are now 48 times more toxic to bees, and every year global insect populations are estimated to drop between one and two percent.

(Three billion birds have been lost in North America since 1970.)

What’s causing butterfly declines—and how to help

As with other insect declines, scientists say the butterfly losses can be attributed to many factors, including habitat loss, climate change, and pesticide use. While climate change or agricultural pesticide use require big society shifts, there are some things each of us can do to help butterflies.

Because insects have short generation spans, even modest changes to the environment—such as planting native flowers or creating habitat—can have a huge impact on the population, says Grames.

“If you're improving habitat for elephants, let's say, you're going to be waiting decades before you see results of that,” she says. “If you improve habitats for butterflies that can have one to three generations per year, you're going to see a pretty immediate increase in population.”

Of course, participating in butterfly monitoring programs like the ones scientists used to analyze trends across U.S. butterfly species is another way to make a difference.

“I think that’s one of the most optimistic things,” says Grames. Butterflies “do have the ability to bounce back, if we put the effort into conservation actions.”