A daughter's epic quest to find one of the rarest butterflies—named after her father

Photographer and National Geographic Explorer Rena Effendi learned that a little-known species was named after her late father, a renowned butterfly expert. The discovery took her on a journey across war zones.

My father once told me that the average lifespan of butterflies is seldom more than a few weeks.

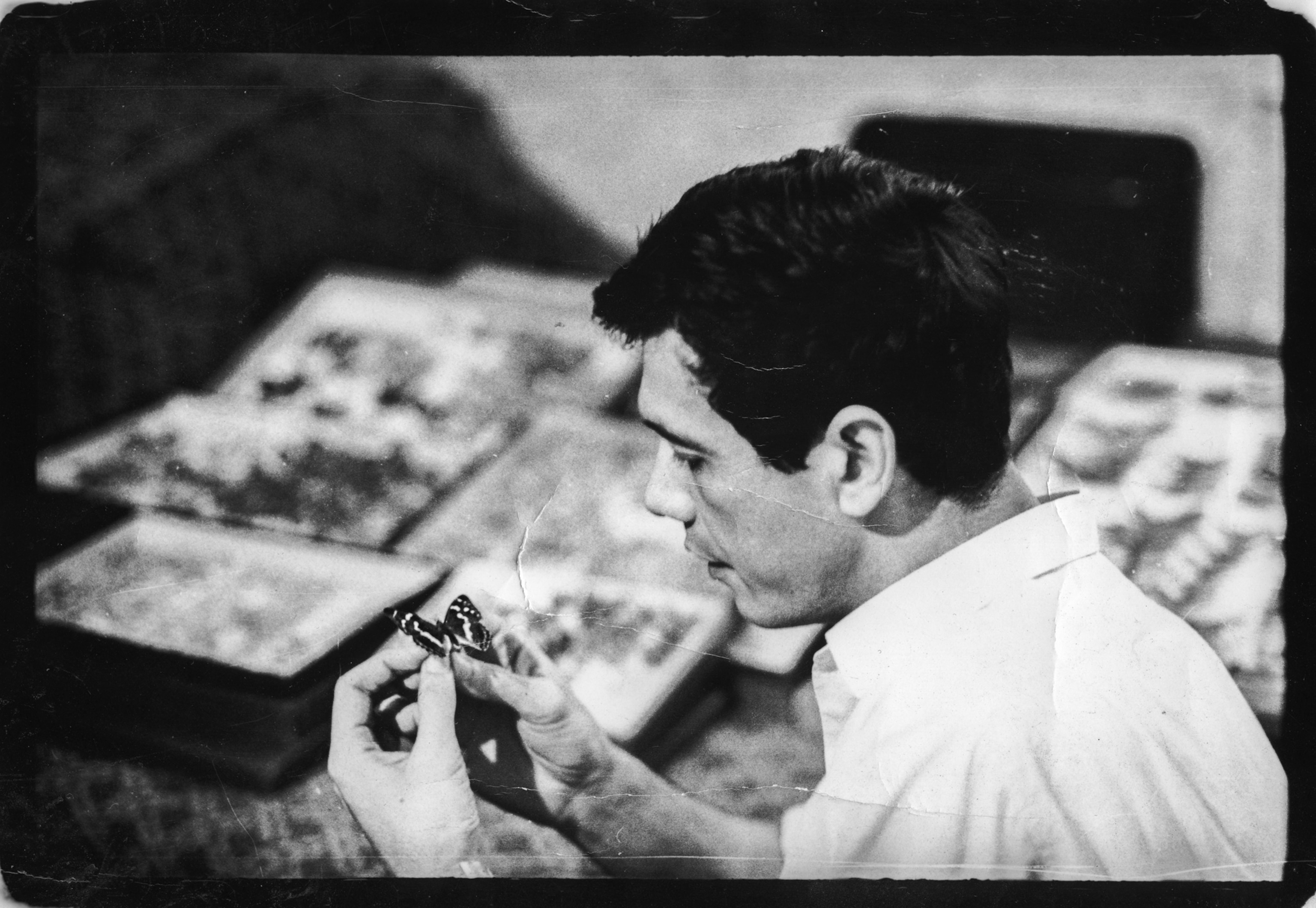

Obsessed with them since he was a boy, he caught thousands during his lifetime. Using pins and tweezers, he’d straighten their wings on a wooden spreader, not a single antenna damaged. He’d then affix the insects to a foam board by piercing tiny needles through their thorax and apply chemicals to preserve their bodies and wings. He’d meticulously arrange butterflies and moths according to their species and family in display cases. With the help of a magnifying lens, he’d inscribe their Latin names on labels smaller than a sunflower seed. Encased in glass, his specimens glistened.

My father, Rustam Effendi, was a Soviet Azerbaijani lepidopterist, a preeminent authority on butterflies and moths of the Caucasus region. In my childhood home, in Baku, Azerbaijan, he was a rare guest. He spent most winters hibernating in his studio apartment in a different part of the city, waiting for the butterfly season to begin in late spring. As soon as the last patches of snow melted on the lower plains, he’d journey into the mountains to study, hunt, and collect. He’d bring back cocoons in jars, caterpillars squirming in matchboxes, and butterflies folded into envelopes, all of which he fussed over with the keenness of a mother tending to her newborn.

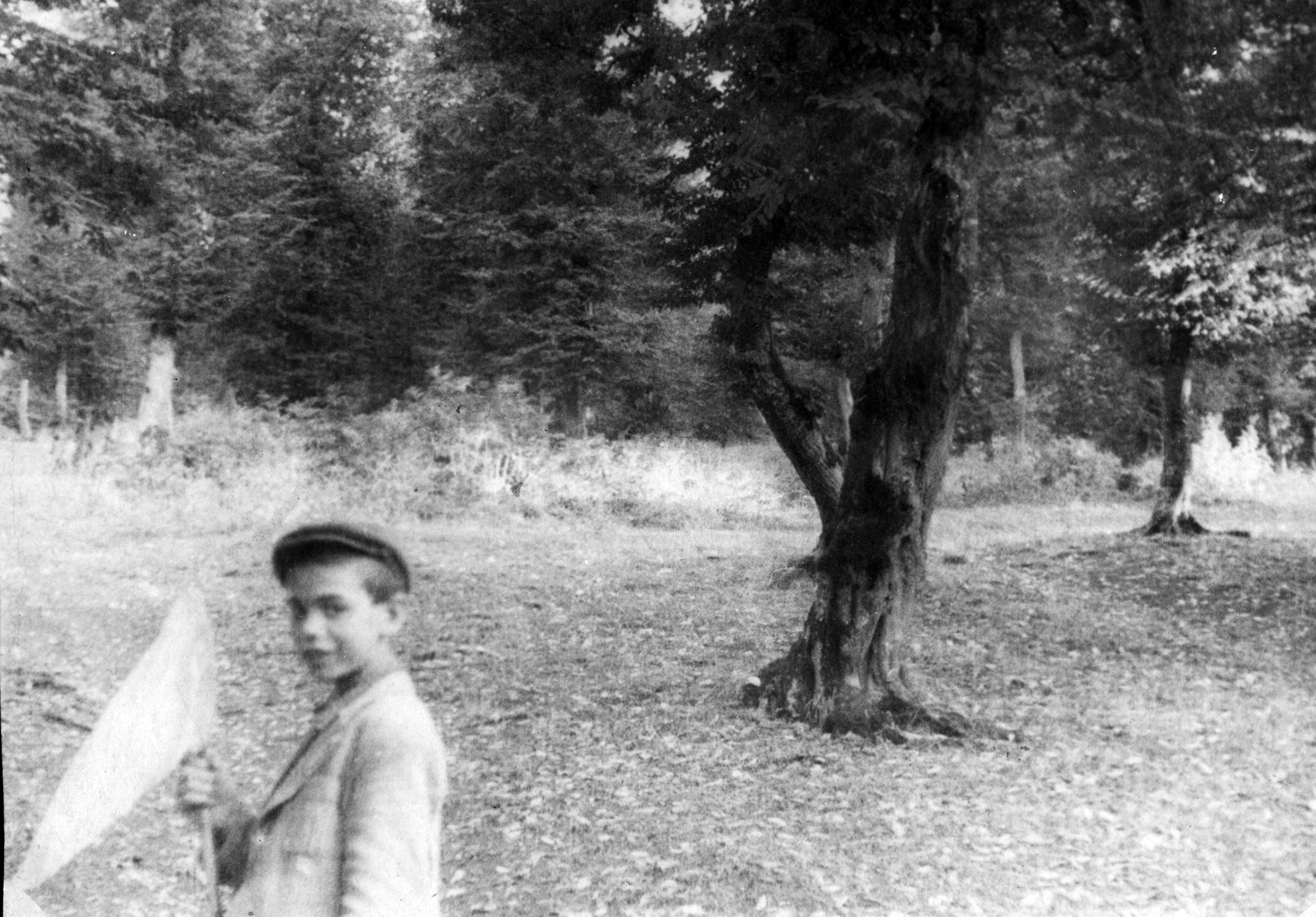

He dedicated his life to his work and died in his mid-50s when I was turning 14. I hardly knew my father. My memories of him are disparate snippets, a collection of faded photographs and conflicting accounts. Over the past three decades as a journalist and photographer, I became fixated on reconstructing the story of his life.

Several years ago, I came across his Wikipedia page and clicked on a link that led me to a picture of a modestly colored butterfly. The description underneath read “Satyrus effendi, species of the Nymphalidae family.” At the bottom of the page, I learned that Yuri Nekrutenko, a lepidopterist from Ukraine, discovered a new butterfly species in the Caucasus in 1989 and named it in honor of Rustam, his close friend and colleague. Later I found out that Yuri had joked with my father at the time: Since you’ve only had daughters, your surname will live on with the butterfly. Let’s hope it does not go extinct.

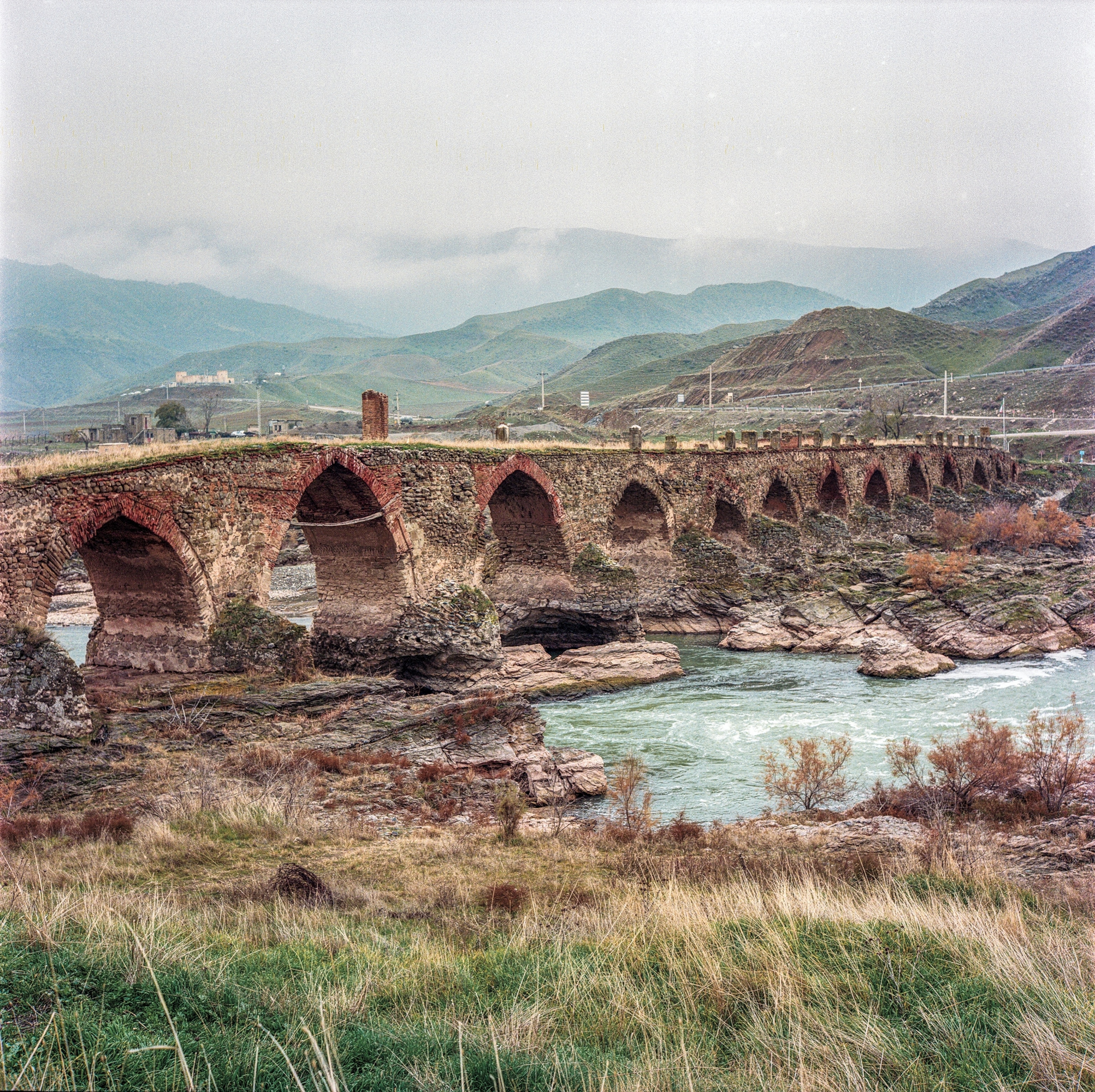

But his namesake is perhaps one of the rarest butterflies in the world. Only a single generation hatches between mid-July and mid-August, flying in its mountainous habitat 10,000 feet above sea level. To withstand harsh conditions, Satyrus effendi has furlike scales on its wings and a dark brown color that may keep it warm. Its most distinguishable physical trait is two black markings, like eyes with white pupils, each glaring from the corner of the wings. For two weeks, the insect flutters over the Zəngəzur ridge, which spans a hundred miles across the border between Azerbaijan and Armenia, two countries in the grips of a decades-long conflict.

(To save monarch butterflies, these scientists want to move mountains.)

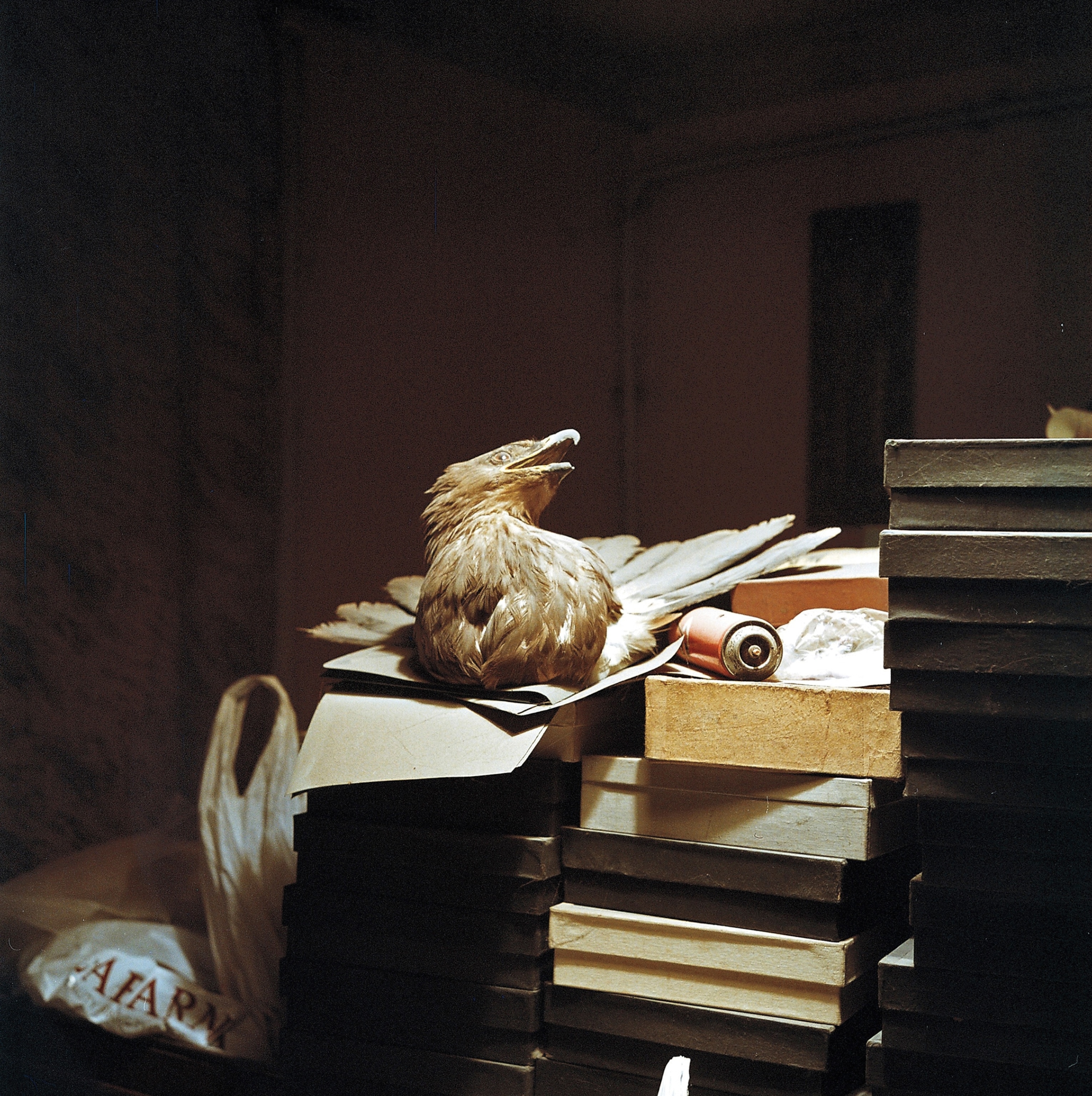

As one of the few lepidopterists in Soviet Azerbaijan, my father captured numerous species, each one stored at the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Zoology in Baku, where he worked for more than three decades. Many years have passed since, and much of his collection is turning to dust. I searched for mentions of Satyrus effendi in scientific works he authored, in his field journals, and among the remaining specimens in his collection, but found no trace of it. I concluded it was one of the only endemic species he hadn’t caught. I wondered if I could.

My father’s hunting grounds

To find the butterfly, I laid out a path retracing my father’s footsteps, consulting the maps he had made of the places he had traveled, a research area that is now constrained by the politics of the day. Despite his reputation as one of the Soviet Union’s leading butterfly and moth experts, he was never able to obtain a doctoral degree because he adamantly refused to join the Communist Party. The decision narrowed his career options: Authorities forbade him from traveling outside the U.S.S.R.

So instead, he crisscrossed his home region of the Caucasus, marking his maps with black dots to show where he’d hunted. A constellation of them run along the southeastern mountains toward Armenia. The world he traversed in those days has changed dramatically. When he died in 1991, the Soviet Union was on the brink of collapse, and wars loomed in the Caucasus. Today the plains and mountain passes where he had peacefully hunted more than 40 years ago would be largely unrecognizable to him. Those changes—wrought by time and conflict—added new obstacles to my journey.

A hostile habitat

Ideally, I would have traveled overland from Azerbaijan into Armenia, as my father had. But the countries are now bitter rivals, their borders sealed and militarized. Since the early 1990s, they’ve fought over control of Nagorno-Karabakh, an autonomous region in the mountains of Azerbaijan, home to a majority ethnic Armenian population. In the 30 years of war and occupation since, the towns and villages my father regularly visited had been reduced to rubble. The Zəngəzur railway—his main transportation across the plains—had long ago been dismantled, its tracks repurposed as anti-tank traps. Many of the fields where he’d hunted for butterflies had been dug out with trenches and littered with land mines.

The conflict is ongoing. Five years ago, Azerbaijan fought a 44-day war to recapture the provinces surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh, which it had lost to Armenia three decades earlier. A ceasefire was brokered by Russia and resulted in a handover of large territories to Azerbaijan. Most recently, in the fall of 2023, Azerbaijan recaptured the autonomous region’s de facto capital of Xankəndi (Stepanakert), displacing more than 100,000 of its ethnic Armenian inhabitants.

To re-create my father’s commute, I petitioned top government agencies in both countries. After months of negotiating, Azerbaijan gave me permission to approach the Armenian border from its territory with a military escort. On this trip, I got to see the same mountain roads where my father traveled by bus or hitched car rides from strangers. But I was never allowed to cross into Armenia.

Clues from the past

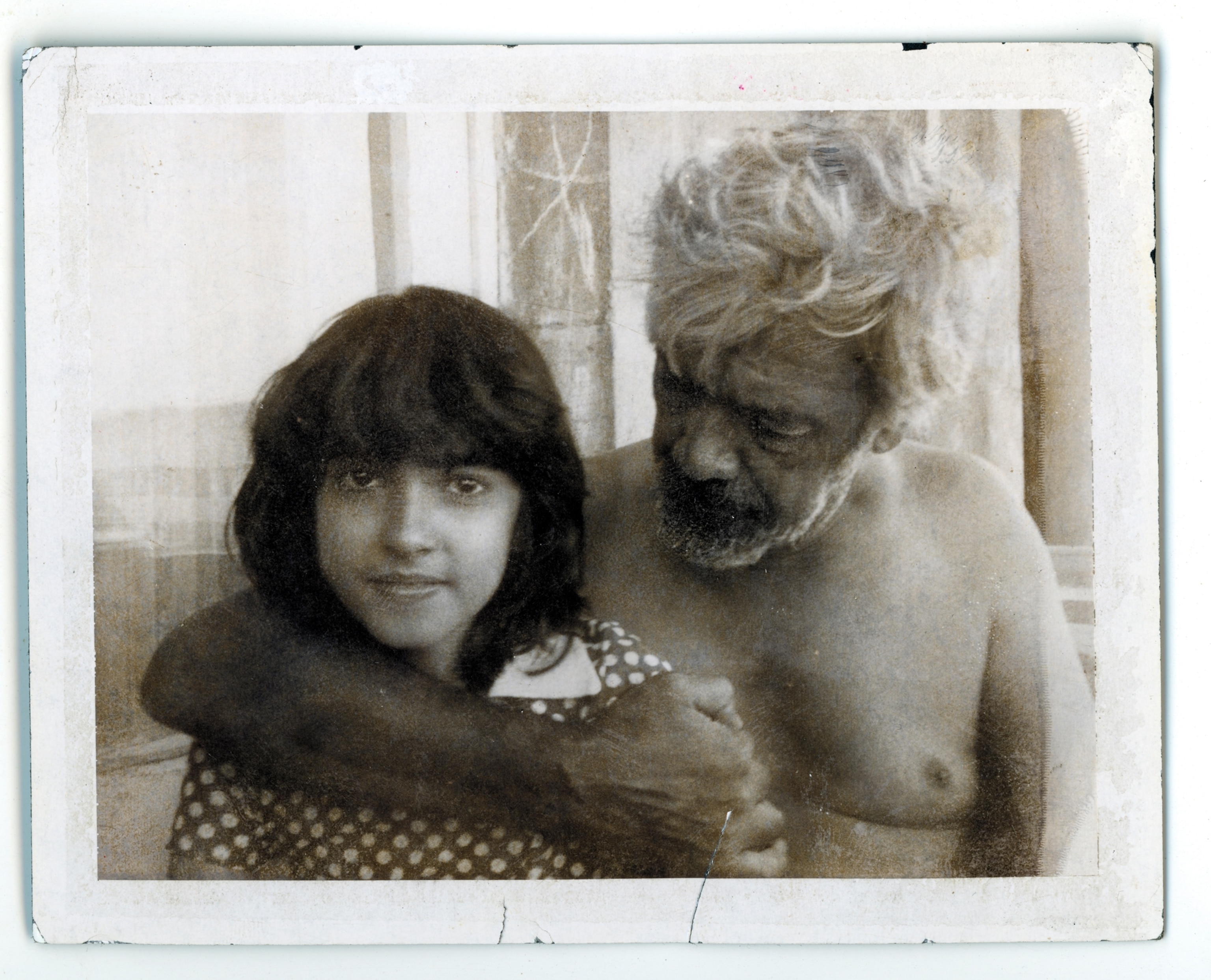

In spring of 2022, I was finally permitted to fly to Armenia, from Istanbul to Yerevan, on one of the first operated direct flights in two years. Ahead of the trip, I was curious if there was someone on that side of the border who still remembered my father. His former colleagues introduced me to Parkev Kazaryan, an ethnic Armenian taxidermist and insect collector. A native of Baku, Parkev, 69, now lives in northern Armenia, in his ancestors’ remote village, where I visited him.

“We were like the two halves of the same apple,” he said of my father, who was 20 years older than Parkev. “He was my teacher, my mentor.” Parkev had fled Azerbaijan amid ethnic tensions in 1989, taking with him his most prized possession: 11 boxes of preserved butterflies. In his sparsely furnished home, time appeared frozen in the late ’80s. A bulky, old Soviet Ukrainian refrigerator held his rhinoceros beetle collection. In one room, under the bed, I noticed a green canvas backpack, identical to my father’s. The sight of it brought back memories of him packing for his hunts, fitting his whole life into a bag like this. Bottomless like a magician’s hat, it contained jars, lamps, vials, matchboxes, a set of tools to spread wings, strips of paper soaked in cyanide (poison for the butterflies), and so much more.

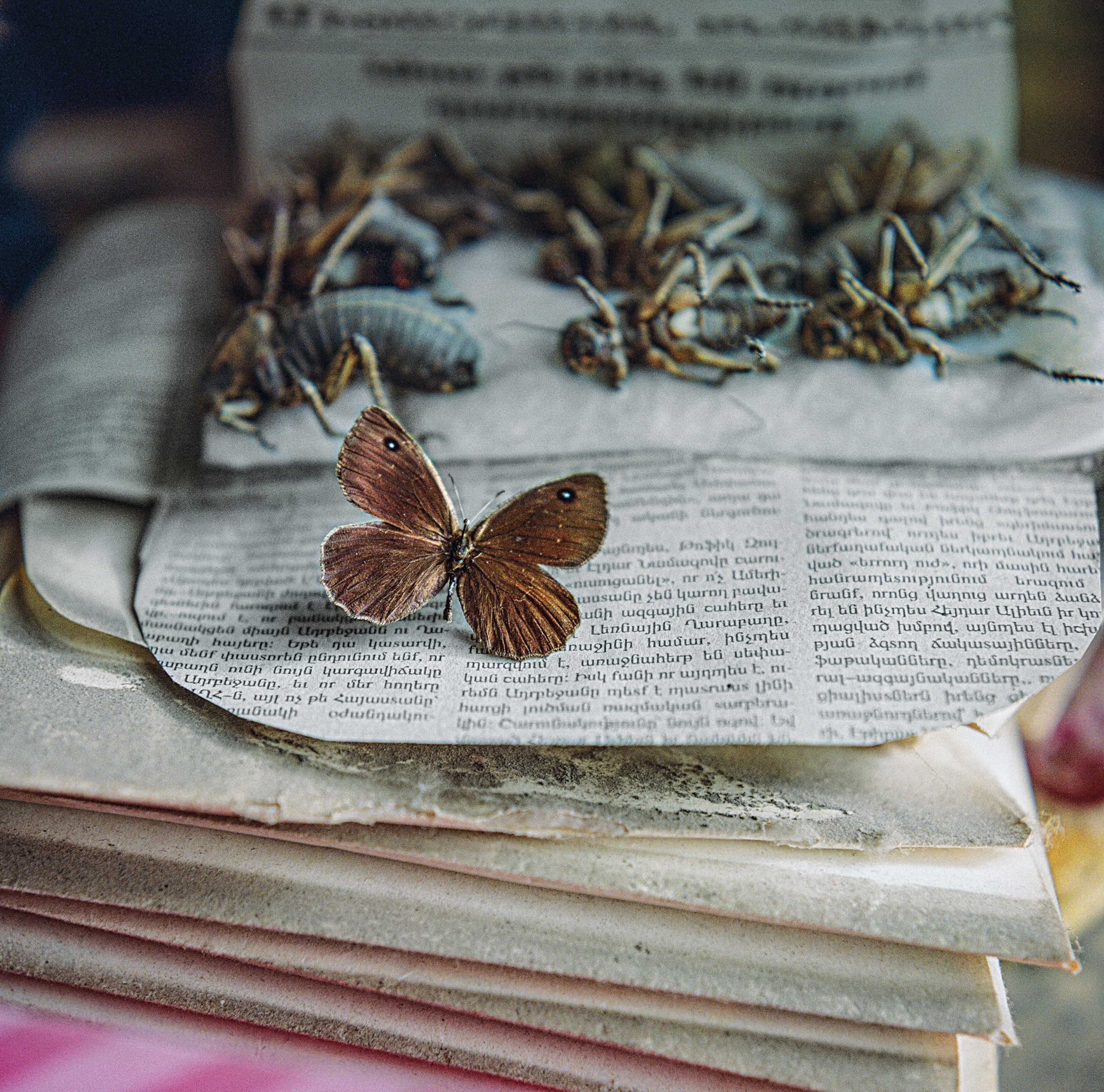

From a stack of dusty boxes, Parkev pulled out a pink one full of pinned butterflies. Two caught my attention: Satyrus effendi. The male was still intact, large and deep brown with velvety, furry-looking wings. Parkev told me he caught the specimens on the Armenian side of the border in the mountains of Vayots Dzor, in the summer of 1991, just a few months after my father died. “It’s not a coincidence I caught it then,” he said. “Rustam made himself known.”

My father’s tools

A few months later, in the summer, I returned to Armenia—this time to search for the butterfly with Parkev where he’d found the pair in his collection more than 30 years ago. Together we traveled up the serpentine road in the mountains of Vayots Dzor in the back of a Soviet Army all-terrain vehicle. We combed the idyllic mountain plateau, carrying translucent butterfly nets. Round at the bottom, not pointy like the regular kind, the net was attached to a bamboo stick with a brass grip, just like my father’s. “This is Rustam’s technology; the net is in the shape of a woman’s bra. You go whoosh, like that,” said Parkev as he swung it. As the sun set behind the jagged rocks on our first day, we left empty-handed. “Ah, Rustam, I hope you’re watching us from up there,” Parkev said, pointing theatrically toward the sky. “We’ve arrived at your Parnassus!”

We returned to the same spot every day for a week, but the butterfly evaded us each time.

(How a caterpillar becomes a butterfly: Metamorphosis, explained.)

The mythical butterfly

Aside from Parkev, there are only two other people alive today who are known to have encountered Satyrus effendi in nature. One of them is a Russian entomologist named Dmitrii Morgun, who observed a small cluster as recently as 2016 flying over the Zəngəzur ridge in the Naxçıvan Autonomous Republic, an Azerbaijani exclave bordering Armenia. For three years, I enlisted Dmitrii’s help and expertise.

“It’s a truly mythical butterfly,” said Dmitrii, who told me my father’s work influenced his early career. “The habitat is so remote and inaccessible, most scientists refused to believe it actually existed.” Satyrus effendi appears to have gone extinct in a few of its early known habitats, including where it was first discovered by Yuri Nekrutenko. And its threatened populations are even more vulnerable because the rise in global temperatures has forced shepherds to graze their flocks at higher altitudes, and the animals feed on the same cereals as does the butterfly species.

After ascending the wrong part of the ridge on my first attempt, I came back to Naxçıvan in the summer by air, circumventing Armenian airspace by flying over Iran. Dmitrii joined me to identify the exact location on Zəngəzur ridge where he had found the butterfly several years ago. The steep, seven-hour climb—part scree, part narrow goat trails—was more arduous than my previous one. I kept asking myself, What am I doing? Unlike my father, who was at home in the mountains, I have felt more at ease in the city. About halfway through the climb, my heart was beating frantically, and I was dizzy with vertigo. When we finally reached the top, there were no butterflies in sight. As I recovered the following day, Dmitrii speculated the shifting seasons made it difficult for us to predict the timing of their hatching.

My discovery

For a third straight summer, I trekked up the mountain in 2023. Muscle memory had formed over time, and I was fueled by my own stubbornness. Dmitrii accompanied me again, but on this trip, we opted to bring packhorses and set up camp for four nights. Temperatures dropped drastically after sunset, and my tent flapped in the persistent wind. Every day at dawn, we ascended the ridge to hunt. And each day, we returned having seen nothing.

After five days of this, I was exhausted. I had hardly slept, and I had begun to come to peace with the idea that I would never see Satyrus effendi in flight. Yet I also realized that my pursuit had achieved something else: It had brought me closer to my father. I walked in his beloved meadows and mountain peaks, where I knew his spirit roamed free. I met people whose faces lit up as they remembered him. I’d gotten to know his old friends, who opened a window into his life. I had come to know him better than I ever did when he was alive.

As Dmitrii and I packed up the camp on our last day, the sun suddenly appeared and the wind subsided. So we decided to search one last time. While hiking, we came across a single bush of Stipa, an endemic feather grass swaying gently in the wind. A food source for the species’ caterpillars, the grass was a sign both hopeful and discouraging. We presumed more of it had been consumed by livestock.

(Butterflies get all the love—but caterpillars may be even more stunning.)

Around noon we sat down for a break, and I closed my eyes to rest. When I opened them, I saw a large dark insect rapidly flying 12 feet above me. “It’s him, it’s him!” I screamed, pointing. Dmitrii sprang to his feet and ran in the direction of the northern slope, bouncing on rocks like a mountain goat. I ran after him but couldn’t keep up.

Dmitrii confirmed it was definitely my Satyrus effendi. There was no doubt I spotted the male species. As I stood up on the spine of the ridge scanning the slope, it flew right over me once again. For a flash of a second, the brown shimmering wings appeared in stark contrast with the sky and the sand-colored terrain. “It’s here, it’s flying!” I yelled again to Dmitrii, and we both watched it dive over the steep, rocky cascade and disappear farther down the slope.

(Painted lady butterfly takes one of longest insect journeys ever recorded.)

An Explorer since 2022, Rena Effendi is a photographer, writer, and filmmaker based in Istanbul.

The nonprofit National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded Explorer Rena Effendi's work. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers