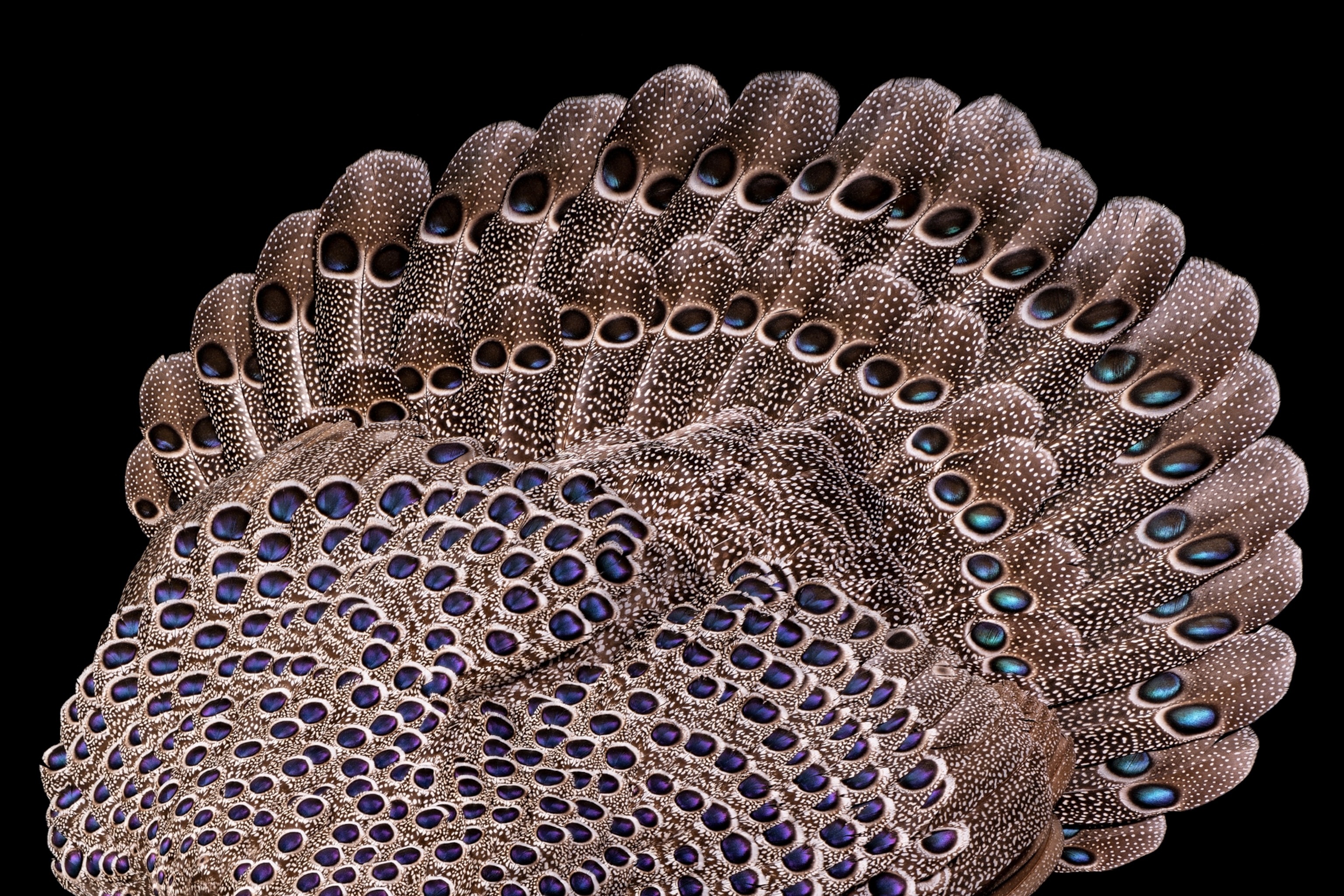

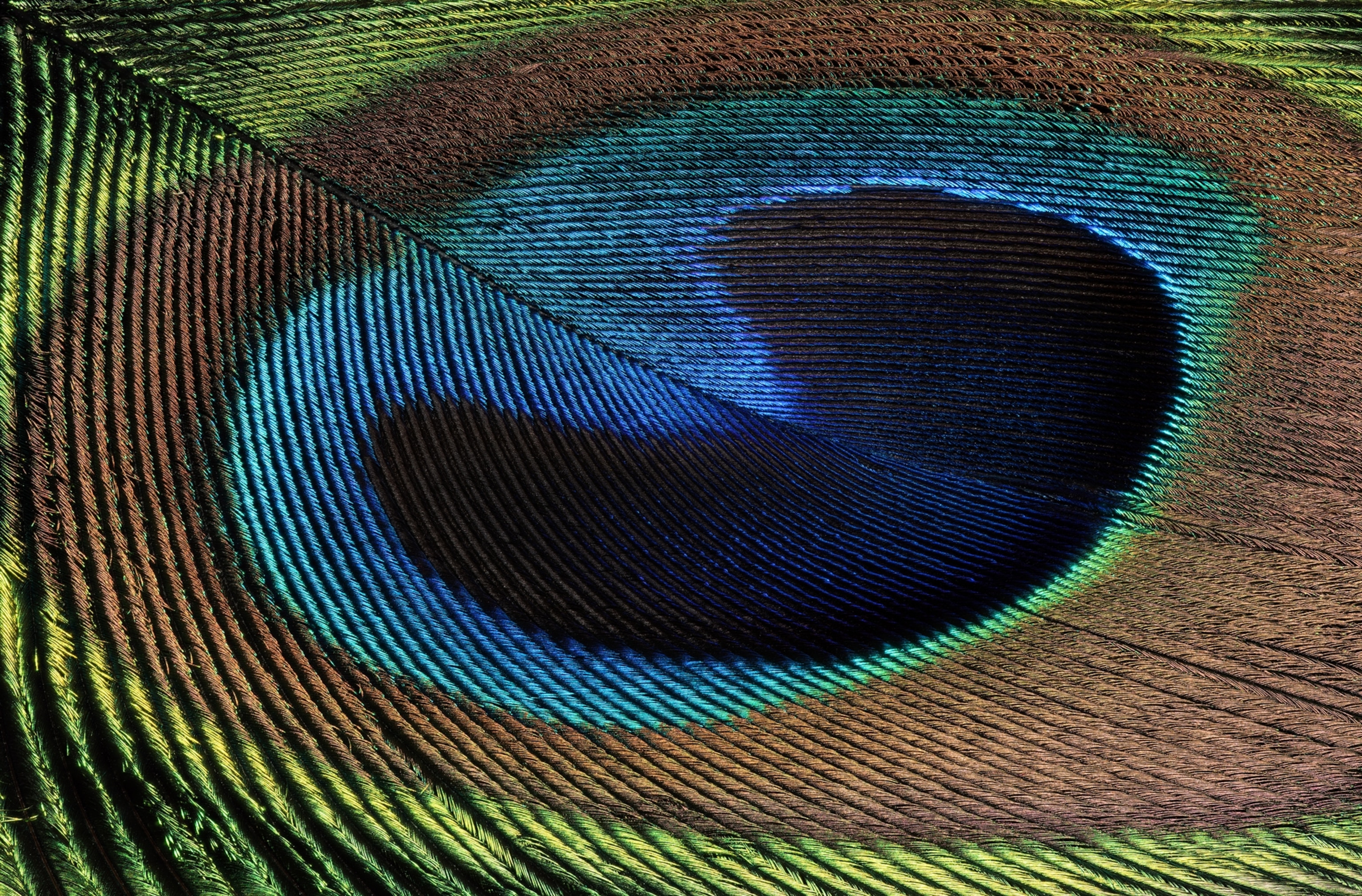

In 1860 Charles Darwin wrote, “The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!” The plumes were so extravagant, he surmised, they could be a hindrance to survival. Darwin’s frustration with their seemingly inexplicable elegance eventually led him to the idea of sexual selection. Although this form of natural selection—driven by the preference of one sex for certain characteristics in individuals of the other sex—is well understood today, a peacock’s feather can still hold mystery for its viewers, says Heidi Koch. She and her husband, Hans-Jürgen, have spent the past few years photographing feathers in all their glorious detail.

The German couple has trained their lenses on the natural world for more than three decades, but they don’t consider themselves nature photographers. They opt instead for a broader label: life-form photographers. In 2020, after several years capturing images of everything from lab mice to bumblebees, the Kochs turned their attention to plumage.

“The beauty and diversity of feathers is so extreme,” says Heidi. That’s why the pair began photographing the most mesmerizing examples from the Museum of Natural History in Berlin and other private collections in Germany. They used a process, called focus stacking, in which similar photos with different focal planes are blended to achieve a more profound depth of field.

Their project, named Feathers—Poetic Masterpiece of Evolution, is an ode to the allure of birds and to evolution itself. Completing it required delving into evolutionary biology, and they sometimes found themselves pondering nature as Darwin did more than 150 years ago. “By the end,” Heidi says, “we really could understand the man.”

This story appears in the November 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine.