Why penguin poop makes krill swim for their lives

A new study shows that the mere presence of poop prompted the crustaceans to launch into evasive maneuvers.

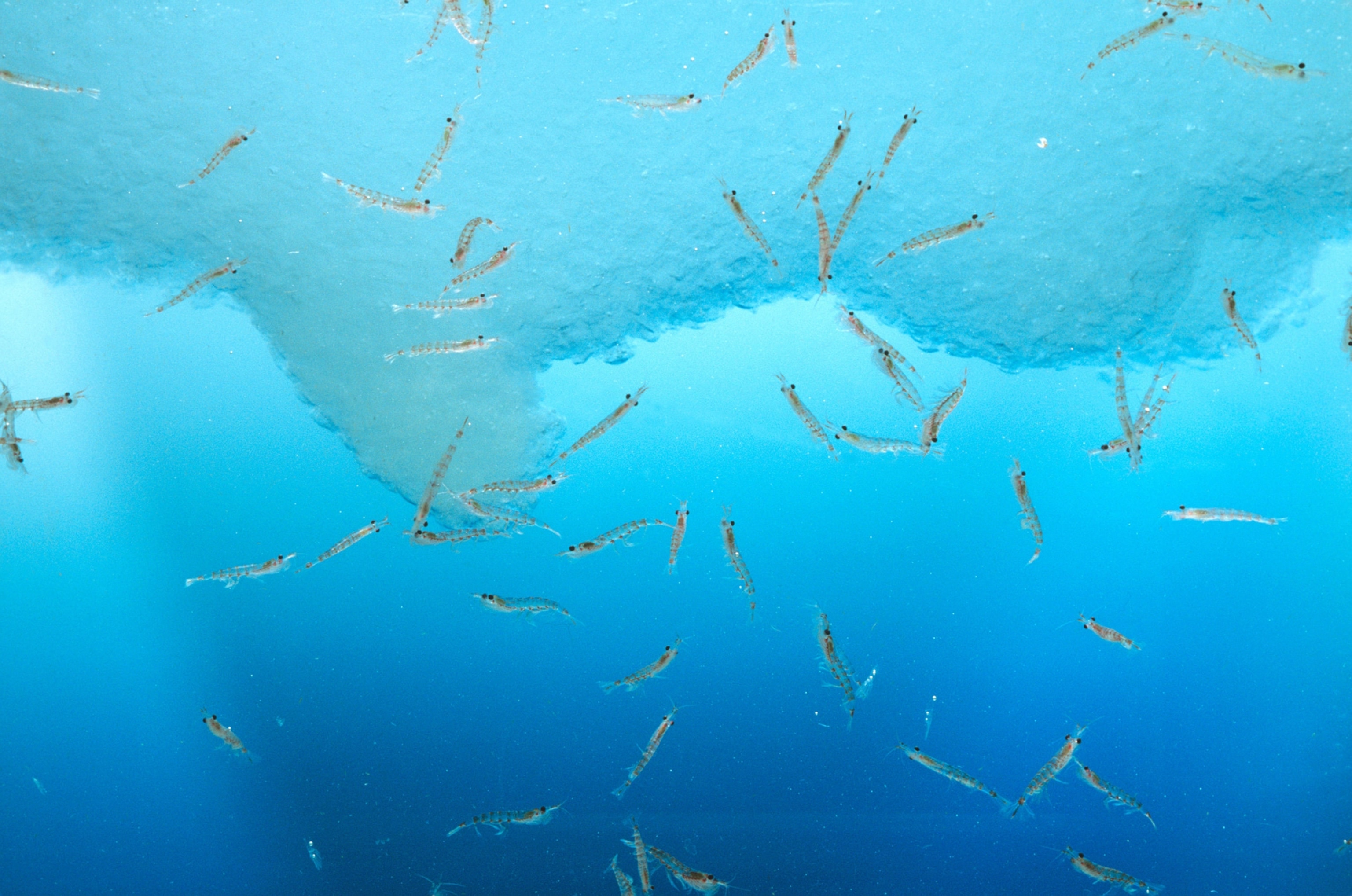

Krill are like the popcorn shrimp of the Southern Ocean—everyone from whales and seals to fish and penguins wants a bite.

But according to a new study, these translucent, pinkie finger-sized crustaceans aren’t as helpless as you might think.

In Antarctica’s Palmer Station lab, scientists put wild-caught krill through a series of tests to see if they could identify the presence of a predator—in this case, Adélie penguins—by squirting a slurry of penguin poop into the crustaceans’ tanks. Because there were just six to eight individuals in each test, the scientists were then able to measure the krill’s reactions.

“You could see straight away that they were having these avoidance behaviors,” says Nicole Hellessey, an Antarctic marine scientist at the University of Tasmania in Hobart, Australia and lead author of the new study published in Frontiers in Marine Science. “They’d start to zigzag all over the place.”

More specifically, the krill swam faster, with three times as many turns—and turns at sharper angles—than usual.

Sometimes the krill would stop swimming altogether, allowing the flow of water in their holding tanks to carry them all the way to the side of the enclosure. Hellessey notes that if the current is carrying the krill away from a predator, then it saves the krill energy to just sit tight and float along with it.

Interestingly, the krill also appeared to lose their appetite in the presence of penguin poop, feeding 64 percent less efficiently than under normal conditions.

(Penguins don't live at the South Pole, and more polar myths debunked.)

With as many as 700 trillion adult krill in the waters surrounding Antarctica, this finding could have huge ramifications for scientists’ understanding of the region’s food web. Hellessey says that while people tend to celebrate the large, charismatic Antarctic animals, such as penguins and whales, krill are the big link that ties everything together.

Escaping the Adélies

Because krill are preyed upon by many kinds of predators, it’s likely that different evasive maneuvers are required of them depending on the situation.

While most people likely picture krill as occurring in gigantic pink clouds, known as swarms, these animals can also be found swimming out in the ocean all by themselves. Both situations carry their own risks.

Humpbacks and blue whales target giant aggregations of krill because that gives them the most bang for their buck, so to speak. At the same time, there is safety in numbers.

“There will always be those krill that are able to just [barely] get out of the way,” says Hellessey.

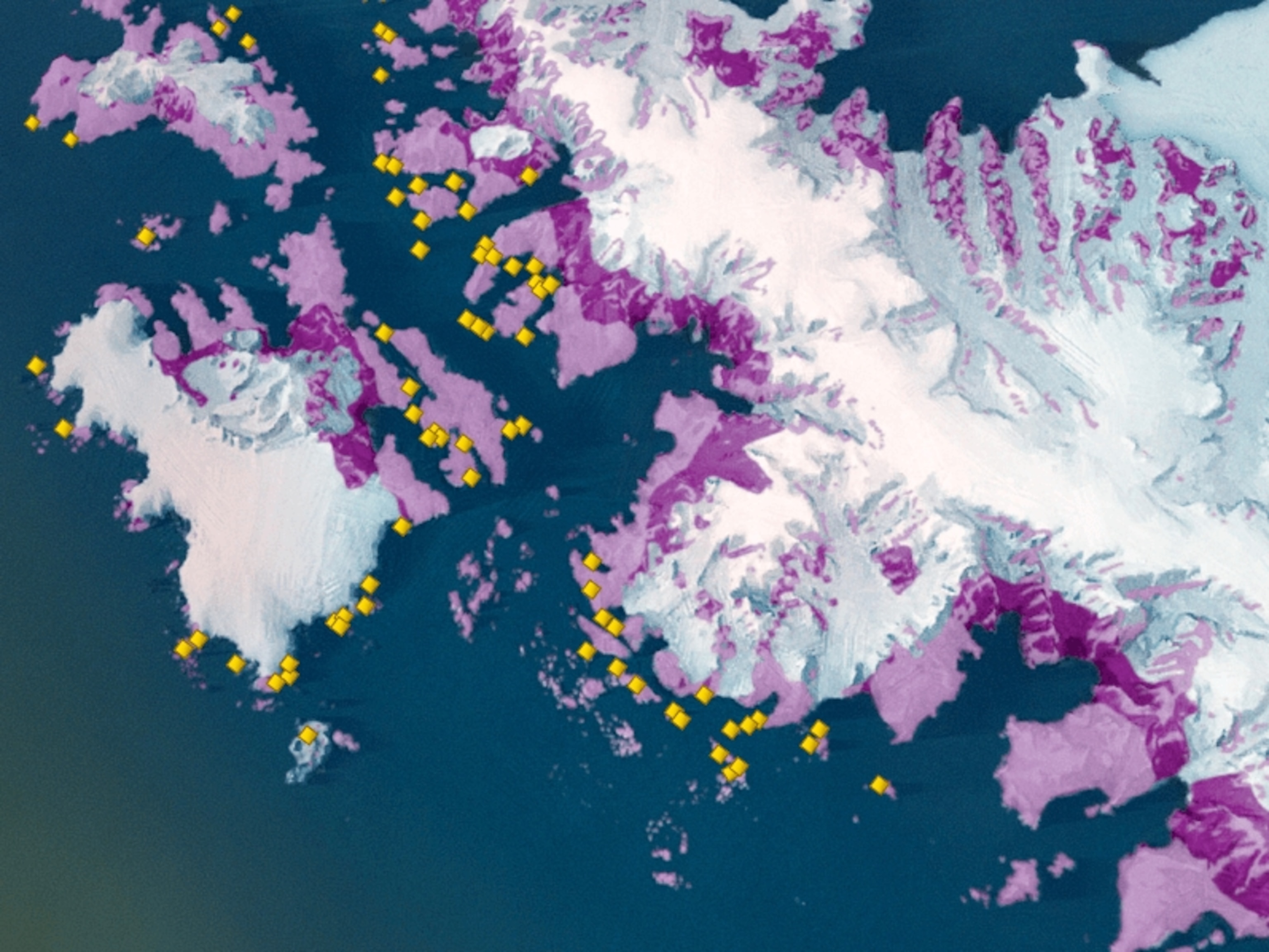

But the discovery that krill can detect penguin guano, or excrement, in the water gives some potential answers to a big mystery. It may be the reason why the crustaceans give large, land-based penguin colonies a wide berth, despite the fact that when penguin poop washes into the sea, it triggers algal blooms, which krill love to eat.

It seems the buffer zone that krill avoid crossing is more evidence that the beady-eyed crustaceans know the predators are close, leading them to stay away.

“That's going to have a big impact on where [krill] habitat is and how close they're able to get to land,” says Hellessey.

Climate change is also driving penguins to colonize new areas, or to stay in regions longer than they normally would, Hellessey notes. And that could lead to negative consequences for krill, given that the new study shows a dip in their feeding ability in the presence of penguins.

(For Antarctica’s emperor penguins, ‘there is no time left.’)

What we can learn from krill behavior

While Kim Bernard, an ocean ecologist at Oregon State University and a National Geographic Explorer, thinks this study is interesting, she isn’t convinced that the krill’s reaction to penguin poop would be enough to drive the broader ecological impacts the study suggests.

“For this to play out at a large scale, guano would need to be present at consistently high concentrations across much of the krill’s range, which seems unlikely since guano is mainly concentrated near penguin colonies,” says Bernard, who was unaffiliated with the new research. “Also, krill have been dealing with penguins for a long time.”

At the same time, she says the research does offer some insight into the connection between predator cues and krill behavior.

“The so-called ‘landscape of fear’ ecological theory comes to mind, where species don’t just respond to direct predation but also alter their behavior in response to the risk of predation, creating a kind of invisible ecological structure shaped by fear,” says Bernard.

For her part, Hellessey would next like to build upon these findings by testing the krill’s response to the feces of other predators, like seals or whales. She also wants to vary the concentration of the solution to see if there’s a minimum threshold that can trigger the crustaceans’ escape senses.

In the end, there’s clearly a lot more to learn about these tiny but critical creatures.

“I think there are a lot of things in the oceans that probably don’t get as much of a heyday as some of the big, cute, cuddly things do,” says Hellessey. “But it’s just as important to study [krill], because without them, you don’t get the cute, cuddly penguins and seals.