An icy world is in meltdown, as penguin population shifts signal trouble

Marine life off the Antarctic Peninsula needs protection as sea ice declines and fishing boats move in to take more krill.

An inflatable boat pulls up next to the snowy shore, and the gentoo penguins of Neko Harbor see people for the first time in almost a year.

Rather than a gaggle of tourists (absent because of the coronavirus pandemic), out climb Tom Hart, a penguin biologist from Oxford University, and several other scientists returning to the Antarctic Peninsula in January 2021. Honks and calls ripple through the colony of about 2,000 gentoos as one of the 2.5-foot-tall birds waddles through to find its nest. The penguins pay no attention to Hart as he makes straight for the time-lapse trail camera perched on a tripod and wedged in place with rocks. He retrieves the memory card from inside the camera’s waterproof housing.

The camera has been taking pictures of the penguins every hour, from dawn till dusk, since they settled down at the nesting colony four months earlier to lay their eggs and rear their chicks. It’s one of nearly a hundred cameras dotted across the 830-mile-long, 43-mile-wide peninsula that have been monitoring breeding colonies of three penguin species during the past decade.

Gentoo numbers on the peninsula have increased rapidly—more than tripling at many sites during the past 30 years—and the birds are expanding south into new areas that had been too icy for them, leveraging their flexible foraging and breeding strategies. In stark contrast, their sister species—the smaller chinstrap penguins and the sleek, black-headed Adélie penguins—have declined by upwards of 75 percent at many of the colonies where gentoos are thriving.

“Very roughly,” Hart says, “you lose one Adélie, you lose one chinstrap, you gain a gentoo.”

Penguins are important sentinels for the wider health of the oceans. They’re highly sensitive to environmental changes and rely on productive seas and abundant prey. Penguin scientists aren’t worried that chinstraps and Adélies will disappear from the planet—some colonies beyond the peninsula appear to be stable, and some may even be increasing.

“What concerns us is that they’re declining so sharply on the Antarctic Peninsula,” says Heather Lynch, an ecologist at Stony Brook University in New York State. Shifts in penguin populations in the waters off Antarctica—the Southern Ocean—are warning signs that the ecosystem is being disrupted. “It really tells us that something has changed about the way the Southern Ocean works and that, no pun intended, that’s the tip of the iceberg.”

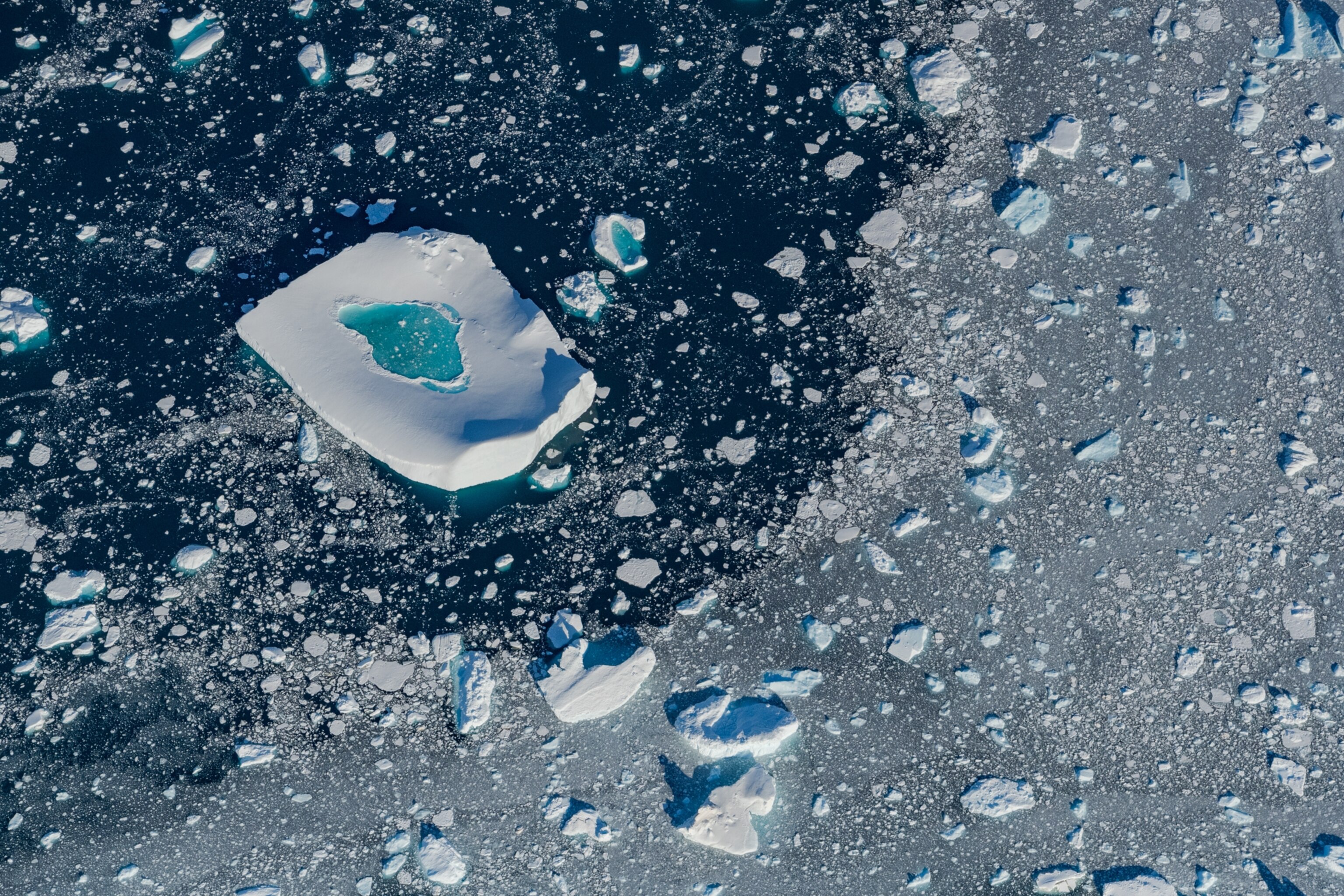

This icy world is imperiled: The Antarctic Peninsula is one of the fastest warming places on the planet. Air temperatures during a heat wave in February 2020 reached a record 64.94°F at Argentina’s Esperanza Base, toward the northern tip of the peninsula. (Summer temperatures normally aren’t more than a few degrees above freezing.) As air temperature rises, sea ice around the peninsula recedes, and in 2016 it dwindled to its least amount since satellite monitoring of changes in the ice began in the 1970s.

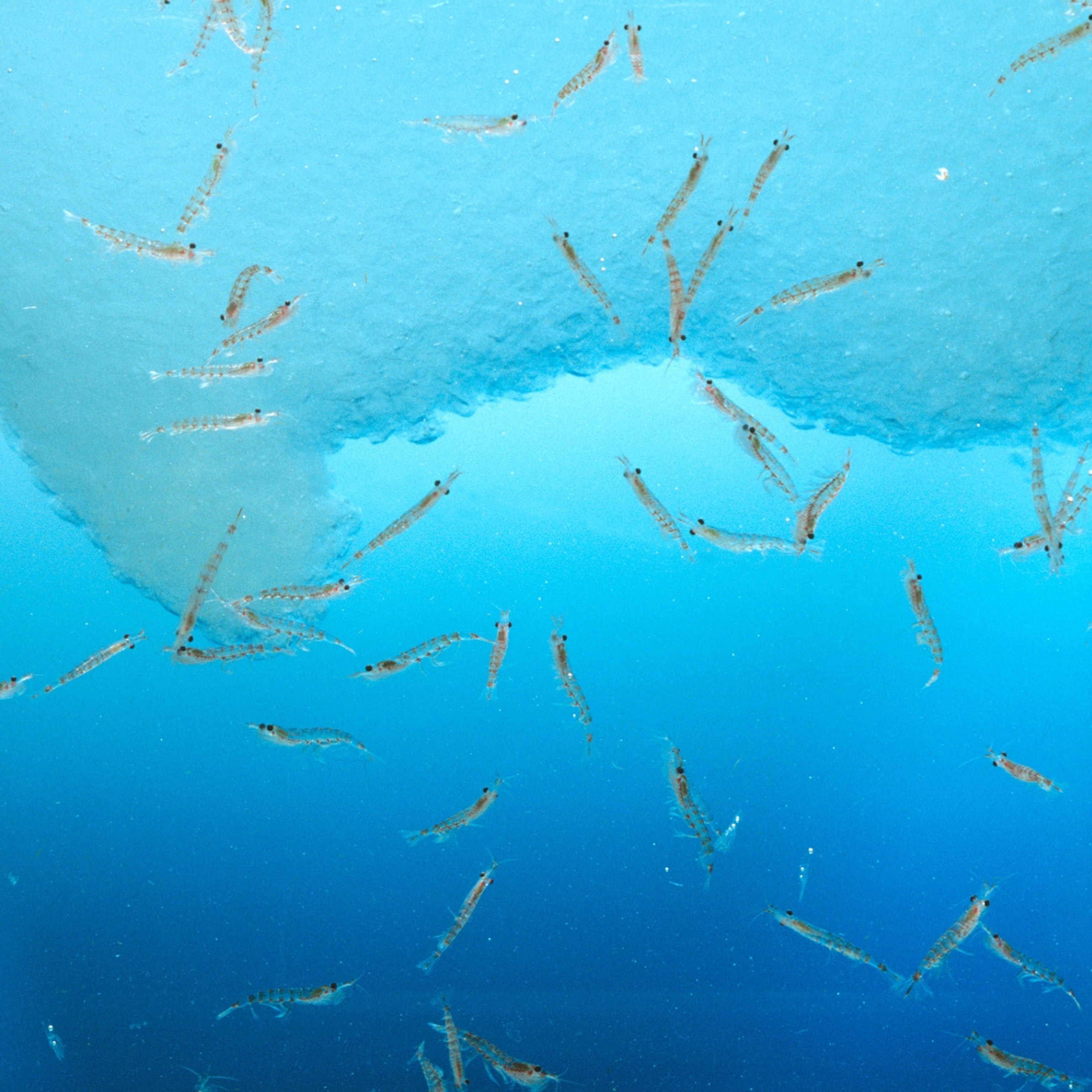

That’s a problem, because freezing sea-water shelters pinkie-finger–size crustaceans—Antarctic krill—that are the key to the web of life in the Southern Ocean. Teeming shoals of krill feed great gatherings of other animals. Minke whales and humpbacks come to scoop up mouthfuls. Squid, fish, and penguins eat krill too. Many of those krill feeders in turn are hunted by top-level predators—leopard seals from below, skuas and giant petrels from above. Take away krill, and the ecosystem unravels.

It’s unclear what quantity of krill has been lost to warming conditions. Meanwhile, the waters around the Antarctic Peninsula supply the largest industrial krill fishery in the Southern Ocean; factory ships extract more than 800 tons a day. Krill are pumped up continuously from nets that may remain submerged for several weeks at a time. The crustaceans are processed on board to make products rich in omega-3 fatty acids, such as fish meal used in livestock feeds and krill oil that’s added to nutritional supplements for humans and pets. Climate change threats and industrial fishing are closely entwined, Lynch says.

“As the sea ice declines, the krill fishing boats are able to move in.”

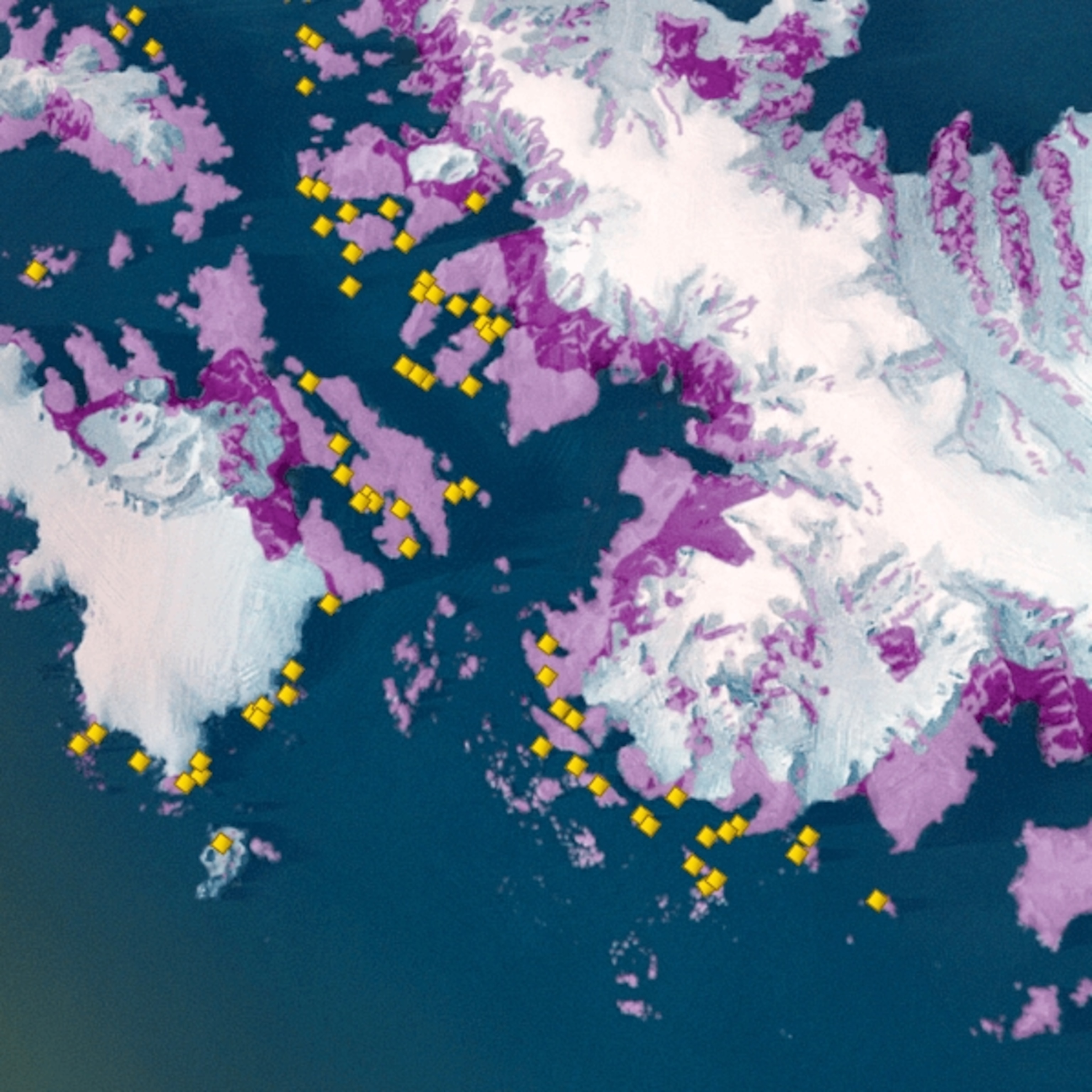

Against the backdrop of these pressures, an international team of Antarctic scientists has drawn up plans for a marine protected area (MPA) covering 250,000 square miles—almost the size of Texas—to safeguard the seas along the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Decisions on whether to create such protected areas are made by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, an international body formed in 1982 to conserve Antarctic marine life in response to increasing commercial interest in krill fishing. The commission operates under the Antarctic Treaty, an agreement signed in 1959 by 12 nations that shelved their territorial disputes and devoted Antarctica to peace and science. Commission membership now stands at 25 countries and the European Union.

Nearly two decades ago, the commission pledged to form a network of protected areas in the Southern Ocean.

The first, established in 2009, safeguarded waters off the South Orkney Islands, 375 miles northeast of the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. The second, finalized in 2016, set aside part of the Ross Sea, on the other side of the continent. The commission was to consider the western Antarctic Peninsula proposal and two others at its annual meeting, in late October 2021.

The proposed measures for the western Antarctic Peninsula would keep krill boats away from the most important waters identified for wildlife within four general protection zones. The largest is in the south, an area that hasn’t been exploited, because it’s covered in sea ice. It would be off-limits to commercial fishing in the future, even if the ice melts enough to make commercial fishing possible. The rest of the protections would designate a zone where krill fishing could continue under renewed regulations.

A proposal to help preserve wildlife on the western Antarctic peninsula as temperatures rise would create four protection zones.

The first steps in setting up an MPA involve gathering scientific data on what’s there. Starting in 2012, scientists from Argentina and Chile led that effort for the Antarctic Peninsula MPA, bringing together experts from around the world. This is an intensively studied part of the continent, with most research bases dotted along the peninsula’s west coast and islands. To identify priority areas for protection, computer software analyzed volumes of information accumulated on the animals that live, eat, and breed in this part of the Southern Ocean.

The Argentine and Chilean delegations sought input from other nations that are members of the commission. “One of our most important goals was to try to build a collective vision,” says Mercedes Santos, a marine biologist who participated in the process as a researcher with the Argentine Antarctic Institute, under the Argentine Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

One objective is to help ensure the resilience of the peninsula’s ecosystems to the changing climate, primarily by regulating where fishing takes place. This is especially important in the Southern Ocean, where so many animals depend on krill.

“An MPA will not prevent the impact of climate change but will reduce the stress on the ecosystem,” Santos says.

The commission has set an annual krill quota for waters surrounding the Antarctic Peninsula of 171,000 tons—less than one percent of the estimated standing stock, as fisheries managers refer to the total biomass. Overall, experts say, that should be an ecologically sustainable fishery, with a caveat: Krill fishing must be targeted.

“For the penguins whose krill supply has dried up, it matters absolutely nothing to them that the krill that was taken was a small percentage of all the krill available in that region,” Lynch says.

“If you explore the fishing patterns in the last 10 or 15 years, they have been consistently going to the same spots,” says César Cárdenas, of the Chilean Antarctic Institute. He’s working on plans for the protected area. Fishing fleets favor the richest areas for krill, where whales and penguins go to feed. A 2020 analysis of more than 30 years of monitoring data indicated that when local krill catch rates are high, penguins do poorly according to a suite of measures including the weight of their fledglings and their breeding success.

Restricting krill fishing in certain parts of the protected area can help ensure the krill populations stay robust in places where parent penguins forage, so they don’t have to compete with fishing boats in securing food for their young.

With the scientific basis of the Antarctic Peninsula MPA in place, the next step lies largely within the political sphere—reaching consensus among all members of the commission. Given the importance of krill fishing, vigorous discussions are likely to lie ahead—especially if negotiations for the Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area, which came into play four years ago after protracted wrangling, are any indication.

Planet Possible

The National Geographic Society’s Pristine Seas project has helped create 24 of the largest marine protected areas worldwide, covering 2.5 million square miles, and aims to help protect at least 30 percent of the ocean by 2030. Learn more at natgeo.org/pristineseas.

The Ross Sea is a deep embayment of Antarctica between Marie Byrd Land and Victoria Land, 2,300 miles south of Christchurch, New Zealand. Dubbed the “Last Ocean” because of its remarkably untouched nature, it’s considered one of the last large intact marine ecosystems left on Earth. Huge numbers of top predators roam its waters: orcas, snow petrels, Weddell seals, emperor and Adélie penguins.

“It has a disproportionate amount of all the amazing marine life that we know Antarctica for,” says Cassandra Brooks, a University of Colorado Boulder marine scientist who has worked in the Southern Ocean since 2004. “It really was this place that the international community rallied around,” she says.

The Ross Sea became a top priority for protection because of climate change and a commercial fishery for Antarctic toothfish that was burgeoning in the mid-2000s. Even so, it took more than 10 years of scientific planning and five years of intense negotiations by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources for the Ross Sea MPA to be adopted.

Discussions stalled over fishing rights and the MPA’s boundaries, and bit by bit, the original parameters changed. Major fishing nations—including Norway and South Korea—cooperated when the MPA was reduced by 40 percent. (Later additions brought the total area back up.) The Ross Sea has no commercial krill fishery, but that option was kept open. Designation of a krill research zone and agreement that krill could be caught in the toothfish fishing zone helped gain China’s support in 2015.

Russia, the last holdout, chaired the commission’s October 2016 meeting, in Hobart, Tasmania. Final adjustments included a sunset clause of 35 years, when the Ross Sea protections will come up for review.

At the end of the two-week meeting, members announced the Ross Sea MPA. It’s the world’s largest marine protected area, covering approximately 589,000 square miles of ocean in addition to 183,000 square miles under the Ross Ice Shelf—in all, an area roughly the size of Mexico.

“Everybody was applauding and hollering and hugging and crying,” says Brooks, who was present throughout the negotiations. “It was truly this remarkable moment.”

In June 2021 the G7, a gathering of government leaders from some of the world’s richest nations, gave its full support to the commission’s interest in establishing a network of protected areas in the Southern Ocean. Along with the Antarctic Peninsula proposal, two other areas—the East Antarctic and the Weddell Sea—are being considered for MPA status. The EU, Australia, Norway, the United Kingdom, and Uruguay are taking leadership roles. The United States—represented by former Secretary of State John Kerry, who was instrumental in the Ross Sea negotiations—is actively engaged again after being on the sidelines during Donald Trump’s presidency.

The October 2021 meeting of the commission was to take place online because of the coronavirus pandemic, with any hugging virtual this time. This year is the 60th anniversary of the Antarctic Treaty coming into force, adding to the optimism of those seeking greater protections for the Southern Ocean. As Mercedes Santos says, “It’s a reminder that we have to do, again, great things.”

Helen Scales wrote about the threats to emperor penguins in the June 2020 issue of the magazine. Photographer Thomas P. Peschak is the director of storytelling for the Save Our Seas Foundation.

This story appears in the November 2021 issue of National Geographic magazine.

Correction: A previous version of this article switched the captions for the gentoo and chinstrap penguin photographs.