Hope swirled through the packed gymnasium of the aptly named Robert Hope Community Center in the Africatown neighborhood of Mobile, Alabama on Thursday, as some 500 residents and descendants of the last known Africans brought in bondage to the United States listened to archaeologists and politicians discuss the discovery of the long-lost slaver Clotilda—and, more importantly, how the historic find might help heal old wounds and attract new investment.

It was an emotional day for many, mixed with the joy of discovery and potential opportunity for this unique African-American community and the painful memories of what their ancestors endured. (See how archaeologists pieced together clues to identify the lost ship.)

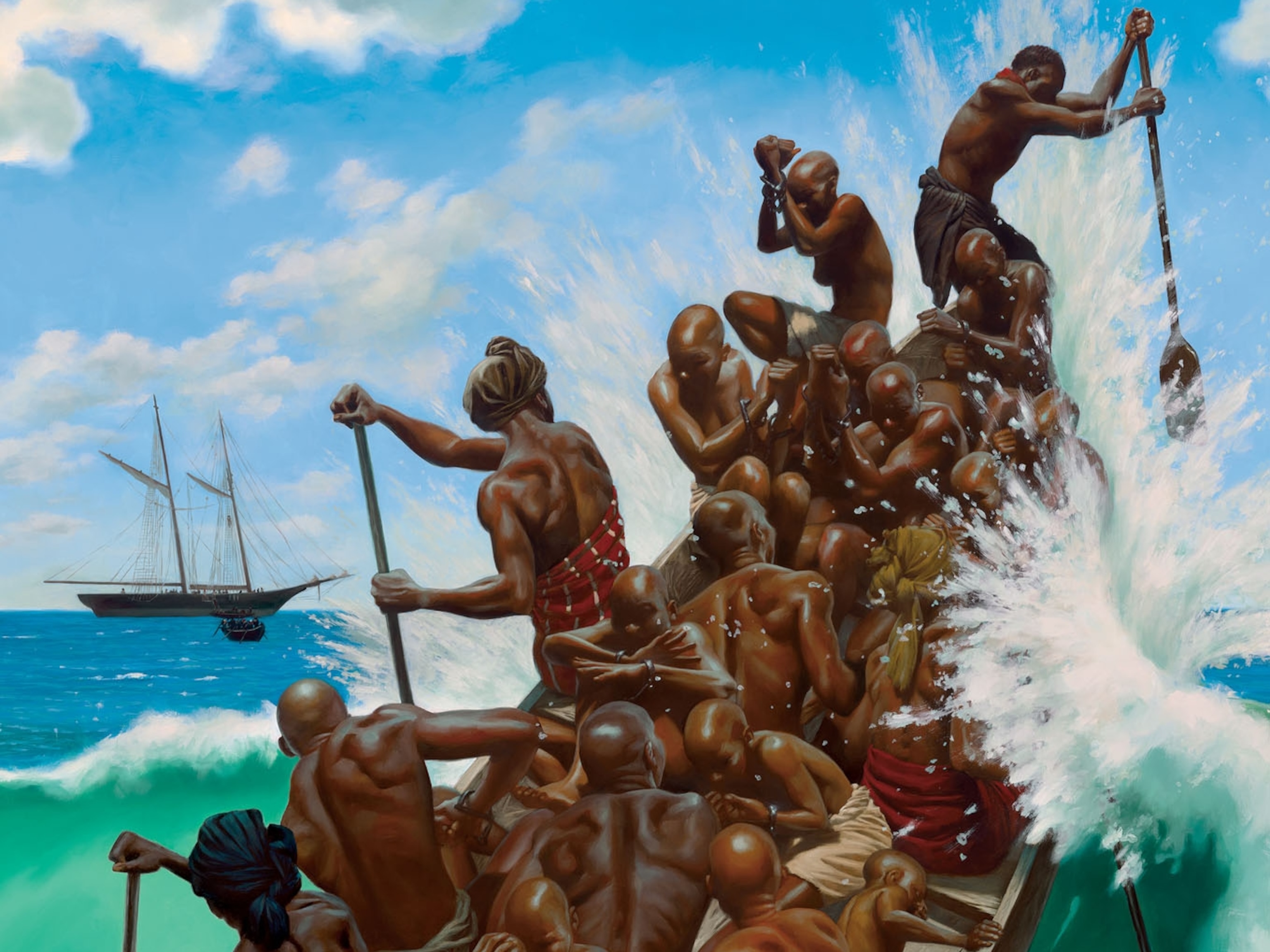

“This was a crime against humanity,” said Kamau Sadiki, the lead diving instructor for Diving with a Purpose and a member of the team that identified the Clotilda. “There is a lot of pain; this community has suffered mightily. I’m humbled and extremely moved by the resilience shown by this community. Now it’s time for justice.”

But how do you right the injustice of 400 years of slavery? At a smaller meeting on Wednesday, one elderly member of the community brought up the subject of reparations.

“After all the pain and suffering our people endured, we need some sort of reparation, especially for the descendants who suffered so,” he said. “Some dollars need to come to the descendants. Somebody needs to take care of us.”

Others disagreed. “Those families were hard-working folks,” said V. Gail Keeby, a descendant of Ossa Keeby, a Clotilda survivor and one of the founders of Africatown. “They didn't ask for a thing from other people. They helped themselves, so we need to continue to stick together and work hard to help ourselves.”

Hope that the Clotilda will spur tourism and economic development was a common refrain throughout the day, particularly given the rising interest in black history, which is undergoing a revival in many parts of the country.

“The African American history museum opened in 2016, and since then we've had five million visitors of every race, creed, and nationality,” said Mary Elliott, curator of slavery at the Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture. “The new lynching memorial in Montgomery [officially the National Memorial for Peace and Justice] brought one billion tourist dollars into this state in one year. This is a story about slavery and freedom, and the power of human resilience and survival. This is an American story.”

Unfortunately, it's a story that has been largely one-sided for more than a century, said Bryan Stevenson, founding director of the Equal Justice Initiative, the organization that built the lynching memorial.

“We’ve preserved hundreds of plantation homes and estates and invited people to examine the lives of slave owners with very little attention to the experience of the enslaved,” Stevenson said in an interview. “This discovery represents what I hope will be a rededication to documenting aspects of the slave experience in America that have gone overlooked and ignored for too long.”

Speakers and attendees voiced many ideas for a fitting memorial, from creating an experience similar to Jamestown or Pearl Harbor, to raising and restoring the entire vessel.

“My ultimate dream would be to have it raised,” said Alabama state Senator Vivian Figures, whose husband, the late Senator Michael Figures, funded a search for the ship in the 1980s. “If we’re not able to raise it, we should preserve what we can and build a replica with video and audio to truly educate people on the experience of those people.”

Ben Raines, the former reporter who initially located the wreck that was later identified as Clotilda, agrees.

“The ship should be raised and put on display in Africatown and become part of the Civil Rights Trail,” Raines said. “It should generate millions of dollars in tourism for a community that needs and deserves it more than anywhere else.”

The feasibility of raising and restoring the wreck is an open question, according to James Delgado, the principal investigator of the state's effort to locate and identify the wreck.

“It’s one thing to study history, another to grow up hearing family stories, and yet another to reach out and touch a piece of history like this,” Delgado said. But such a project would take many years and cost millions of dollars.

The daunting price tag doesn't bother Kern Jackson, an African-American Studies professor at the University of South Alabama who has been involved with the Africatown community for years.

“The U.S.S. Alabama sits in Mobile Bay today, and the children of Alabama were asked to pay a penny apiece to bring it here,” Jackson said. “Why not do that for Clotilda?”

Some have even suggested making the Clotilda the first National Slave Ship Memorial. But Senator Figures is reluctant to speculate so soon.

“I want to keep an open mind until we get the input of the community, with everybody coming together with their ideas,” Figures said. “I liken it to making a quilt. You've got all these different pieces, but when you sew them together you create something beautiful.”