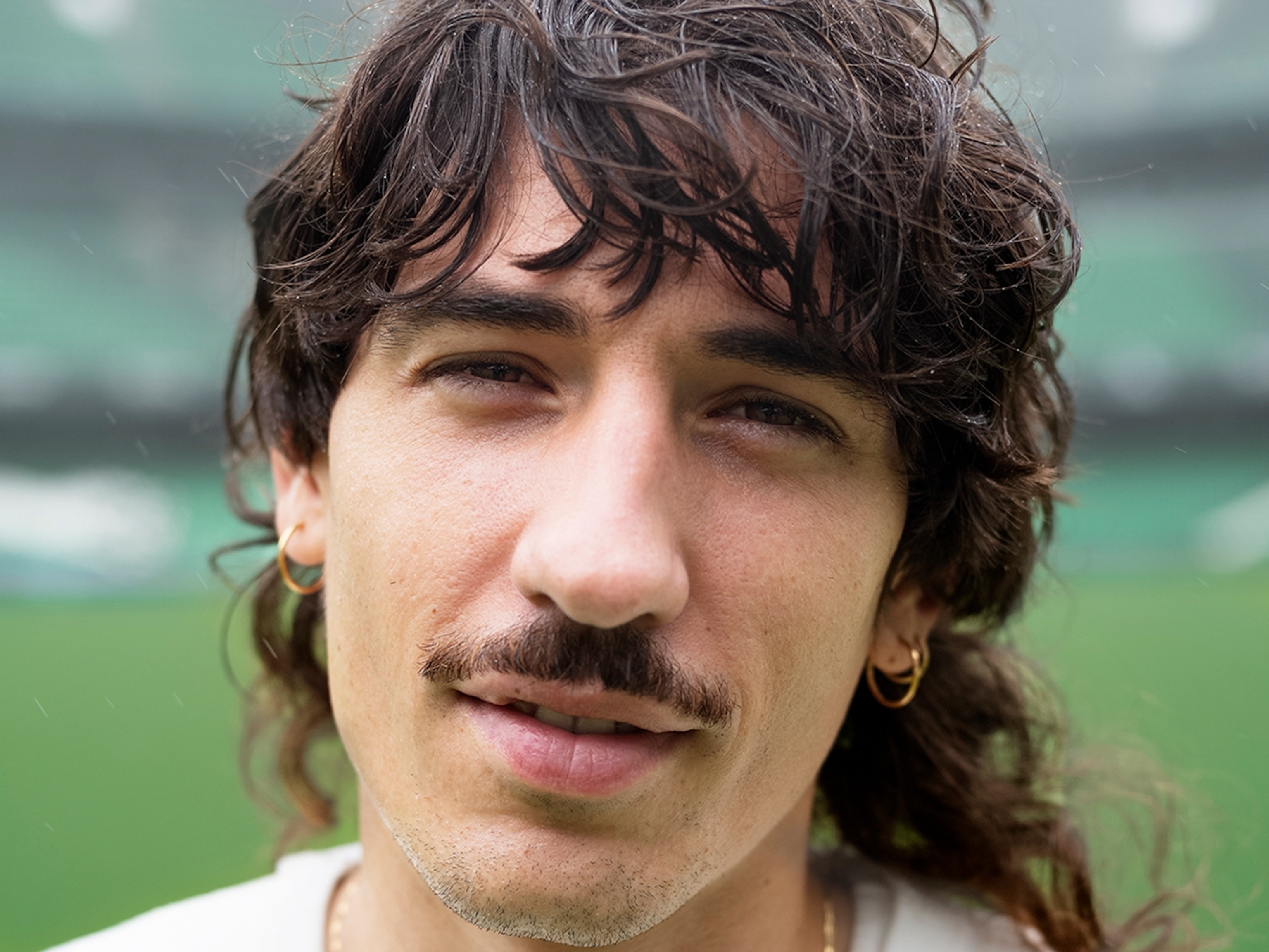

Chobani founder Hamdi Ulukaya believes refugees make companies stronger

Before he was a yogurt magnate, he left Turkey for a new life in America. That experience informs his ideas about how entrepreneurs can help solve the refugee crisis—and improve their businesses at the same time.

The son of nomadic sheep farmers and a member of Turkey’s ethnic Kurdish minority, Hamdi Ulukaya was the first in his family to go to college, enrolling at Ankara University. It was the early nineties, a time of heightened tensions between government forces and Kurdish separatists, and Ulukaya founded a newspaper in which he called out the human rights abuses faced by his fellow Kurds. One day, he recalls, he was taken into police custody. He was only detained for a night, but the experience convinced him that he needed to leave the country. “I was forced to leave,” he says. “I did not leave because I dreamed about going to America.”

He went to an agency that helped him transfer to Adelphi University, on Long Island, New York, where he learned English. Eventually, he started a business importing his family’s feta cheese, and in 2005 he read about a yogurt plant for sale near the city of Utica. Suddenly, he had a vision: He would start his own company making Turkish-style yogurt, thick and tangy. He had no real money, no business education. But he cobbled together a loan and started Chobani (Turkish for “shepherd”). Seven years later, they were doing a billion dollars in sales.

Ulukaya often thinks about others who arrive in this country fleeing persecution. That’s what brought him to the refugee resettlement center in Utica, where he encountered people of some 16 different nationalities. “The only reason they don’t work is they don’t have driver’s licenses or cars,” he says. “And they don’t speak the language. I said, ‘Okay. Similar to me.’” He hired five refugees, then 10, then 300, including Somalis, Nepalis, and Afghans. Over 20 languages were spoken at the yogurt plant, yet he felt that somehow his workforce was more cohesive than ever.

Soon after the European migrant crisis exploded, in 2015, Ulukaya doubled down on his commitment. “The only way we can take this topic above and beyond politics is if businesses get involved,” he says. He founded a nonprofit, the Tent Partnership for Refugees, which has now helped tens of thousands of displaced people find jobs around the world, including with Airbnb, Mastercard, UPS, and Ikea. “Our pitch is that you’re not going to find more loyal, hardworking, and determined people to work for your company,” Ulukaya says. “They’ll never forget that you opened the door for them.”

Recently, Tent has begun matching displaced LGBTQ people with queer mentors and other allies in the corporate world and connecting Afghan refugees with U.S. military veterans, the sort of pairing that Ulukaya calls “magical.” That kind of chemistry is the secret to Chobani’s success, he says. “The whole thing happened because in the early days I made a decision that I will break down these walls and I’ll let everybody be part of this.”

Tent’s mission is now more urgent than ever. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, there are a record 122 million people around the world who have been forcibly displaced. Ulukaya wishes he could help more of them. Often he thinks about two employees in particular, a pair of Afghan sisters who fled their homeland after their father was killed. “I say it loudly: I never give a hand up,” Ulukaya says. “It was just a job.” And then tens of thousands of jobs.