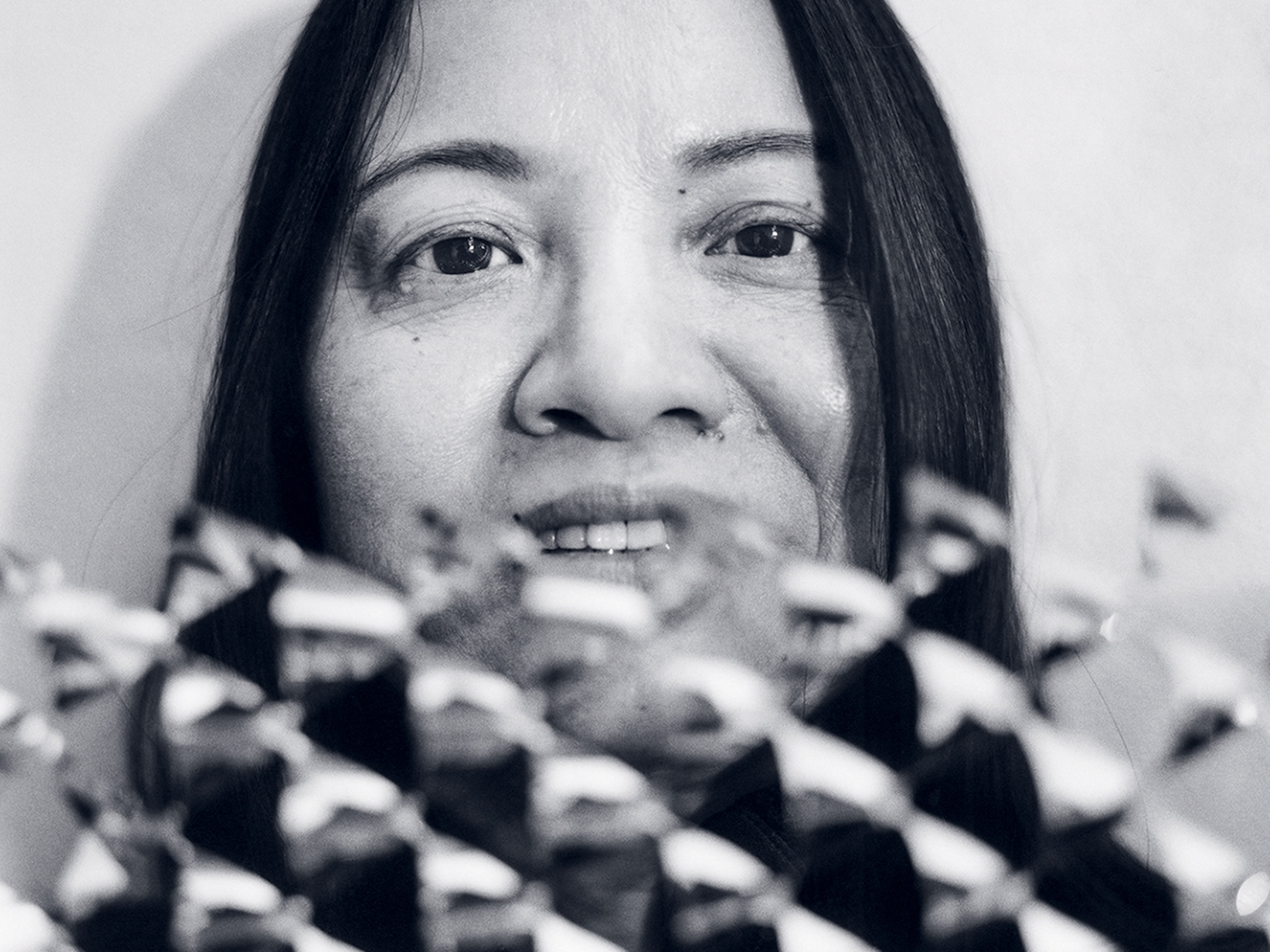

Activist Jennifer Uchendu is highlighting the emotional impact of climate change

In Nigeria, she discovered the rarely discussed burdens of environmental catastrophe. Fostering difficult conversations, she realized, was a necessary first step to finding solutions.

For years, Jennifer Uchendu had been warning fellow Nigerians about the imminent dangers of climate change without realizing that a related issue had escaped her attention: Simply put, she felt increasingly anxious and overwhelmed.

Residents of the global South experience some of the most dramatic effects of climate change—flooded cities, drought-stricken farmland, excruciating heat waves—often without contributing significantly to the problem themselves. For Uchendu, who was acting as a sustainability consultant in local communities and had launched a blog, SustyVibes, to help young people reduce their carbon footprint and encourage more accountability among others, it felt like she couldn’t make a difference fast enough.

International leaders certainly didn’t seem to be taking the challenges that her community faced seriously. “I came from a place of anger and frustration,” she says. “I felt like I either do the hard work of exploring these emotions or I completely give up and do something else.”

Then, in 2020, Uchendu had an idea. She’d seen that United Kingdom activists had established climate cafés: conversational spaces where they processed their anger and grief over the warming planet and renewed their resolve. So she founded the Eco-Anxiety in Africa Project, or TEAP, a Lagos-based organization that helps young Africans meet and talk about the emotions they are feeling around climate change. Two years later, TEAP launched a café in its office, offering a gathering space for its members.

TEAP’s leaders want to inspire a sense of empowerment among the more than 700 people who have joined the project. Whether the goal is to plant more trees or lower an electricity bill, conversations at TEAP often explore intersecting hardships. “In Nigeria, even though we’ve come together because of climate change, it’s not out of place when someone talks about unemployment or the high prices of food, because we see that these are the broader impacts of the problem,” Uchendu says. “Having something locally embedded and contextual means we can feel comfortable to express ourselves.”

She’s since expanded TEAP to several more states in Nigeria, and she plans to train organizers to create similar spaces in South Africa, Ghana, and Kenya. Meanwhile, she’s conducting research with the University of Nottingham, in England, about the emotional impact of climate change for urban residents in large African cities, which may help raise awareness of the problem more broadly.

As Uchendu sees it, providing a venue for young Africans to talk about their eco-anxiety is an essential step in continuing the fight for a better future. “We need to have young people who feel well and can thrive under the circumstances that we have now. If young people feel completely powerless and crippled, it’s not just a public health crisis but a disaster for climate change,” she says. “You have to have the energy to do something.” That’s another valuable resource to protect.