Mexican traditions live on in California through female rodeo performers

Escaramuzas ride sidesaddle, kick up dust, and channel the bravery and horsemanship of Mexican revolutionary heroes.

Snelling, California — On a hot summer day, a mocha-colored horse gallops into an arena carrying a woman in an embroidered, wide-brimmed sombrero and a high-necked red dress ballooning over a petticoat and fitted pantaloons.

The woman rides sidesaddle, her calf-length boots dangling over the side of the horse. She tugs the reins with one hand and the horse begins sliding on its back legs. The long slide lasts a full four seconds, trailed by a cloud of dust—a scene reminiscent of a battlefield during the Mexican Revolution, where female fighters did such things to distract the enemy.

But this is July 4, 2021. The ranch is on the outskirts of a small California town more than 400 miles north of the Mexican border. The woman is 44-year-old Elda Bueno, a competitor on a team of female equestrians known as escaramuzas.

The team of eight performs a synchronized horseback ballet at a full gallop as part of charreadas—Mexican rodeos. Hugely popular with Mexico’s elite, the sport also thrives within diaspora communities in the United States.

Before the escaramuzas’ main event, they do punta, the sliding competition which Bueno has just completed. Two men in full cowboy regalia walk out and extend a long tape measurer, examining the markings left behind by the horse’s hooves.

An announcer relays the result: “Diez y siete metros en tres tiempos!” Seventeen meters with just three lifts of the hoof, a great success.

Friends and family in the stands break into Mexico’s most famous cheer, which has no English translation but is chanted religiously at sporting events: A la bio! A la bao! A la bin bom ba! Elda! Elda! Ra, ra, ra!

Elda’s mother, Hortensia Bueno, cries louder than any other spectator, and her father Juan Bueno captures the moment on his cellphone. If Bueno and her team, Flor de Gardenia— Gardenia Flower—can keep this momentum, there will be a spot for them in Mexico’s national championship this fall. That’s the dream of the self-financed, up-and-coming team that last year made nationals for the first time ever, only to see it canceled because of the pandemic.

The margin of error for victory, however, is exceedingly small. The judges are unforgiving and even the slightest misstep, asynchrony or wardrobe malfunction can result in a disqualification. Falls and injuries are common. The schedule is rigorous. The sport is costly.

Still, these women carry out one of Mexico’s longest-standing traditions.

500 years of horsemanship

Escaramuza translates to “skirmish” and the event is a contemporary addition to Mexico’s national sport, charrería, whose pageantry commemorates five centuries of horsemanship.

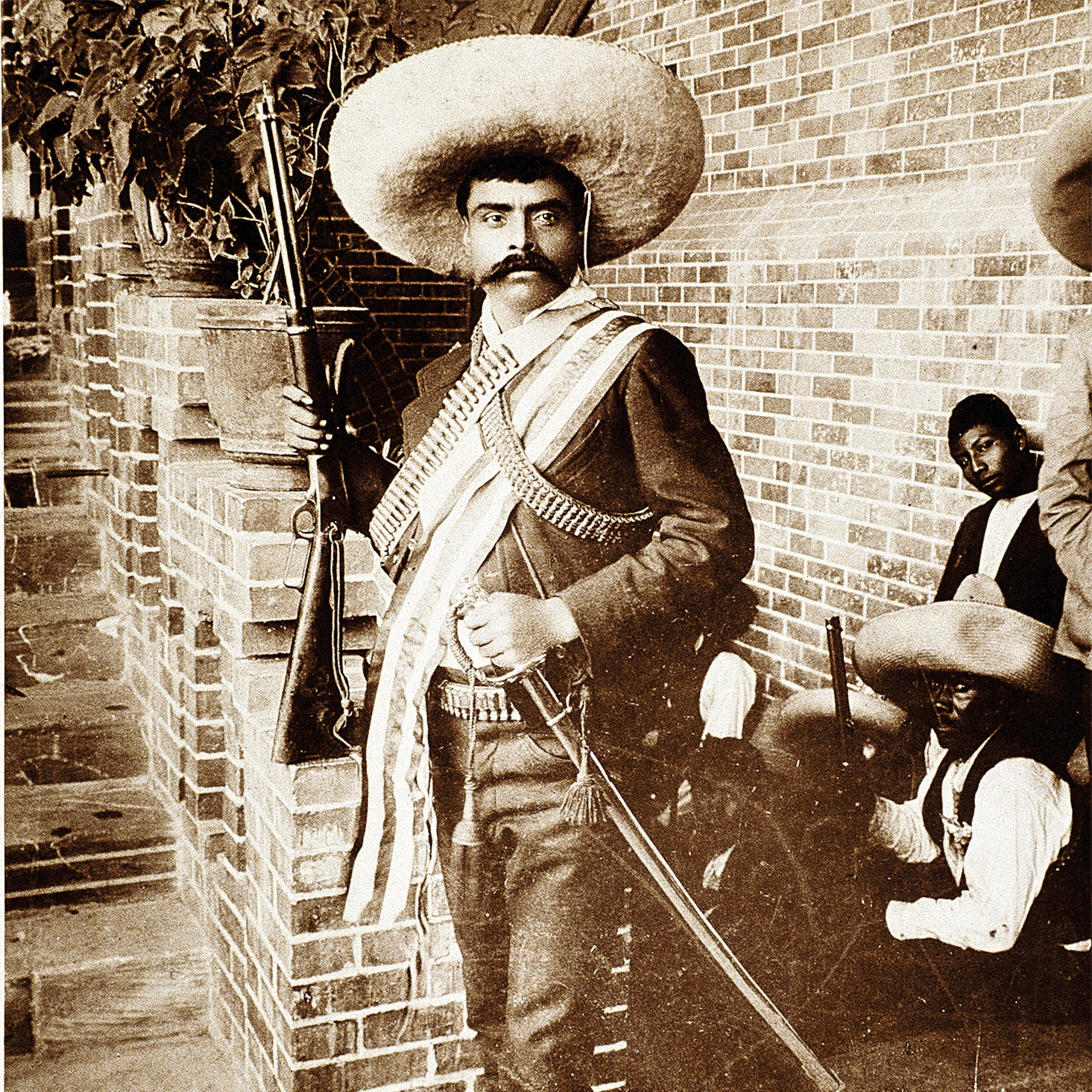

Building on techniques from Spanish riding school and adaptations made by the conquistadors, the vaqueros—cowboys—created a unique style and added things like maguey lassos. The men’s charreada events evolved from hacienda roundups that began in the 16th century, but it was the bravery and riding style of chinacos—ranch hands who fought for Mexico’s independence—and of Mexico’s revolutionary heroes that came to define the sport.

Rules for charrería were formalized in 1919. Because it holds such high import for Mexican identity and culture, playing a pivotal role in passing down social values to new generations, UNESCO declared it Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016.

Escaramuzas began attending charreadas in the 1950s, and soon after began lobbying to compete. It was only in 1989 that the Federación Mexicana de Charrería finally formalized their event, which honors women’s contributions to Mexican history and tradition.

During the Mexican War of Independence, women herded livestock and fought in battle, role modeling for the female soldiers who later enlisted in the Mexican Revolution. The revolutionary general Pancho Villa is said to have had a companion named Adelita, and after she became a legendary fighter in his army, female revolutionaries all became known as Adelitas.

They rode sidesaddle in long dresses and kicked up dust to disorient the Spanish, and their distinct style of dress is the inspiration for the escaramuza costume. Beneath the frill, though, are extraordinary riding skills.

The women are oftentimes more passionate than the men, and far more organized, says Juan Luis Quezada, president of California’s division of the Federación Mexicana de Charrería. “Anything you put in front of them, they achieve it,” he says, smiling. “They come and make us look bad.”

Devotion and relentless practice

At Elda Bueno’s ranch two nights before the competition, team members gather for an intense practice ritual.

Captain Elda warns against point deductions in a mash-up of English and Spanish peppered with horse vernacular, essentially an escaramuza language. “Do not let the legs move,” she says. “Why? Because that will cost my abierto (deduction for spacing) and that will cost my desplazamiento (deduction for traveling)… We’re not all going to girar (turn). I understand that. I can live with that. But I cannot live with an abierto and a desplazamiento.”

Every one of these women has fallen off a horse, suffered concussions and broken bones, been dragged and trampled. Most have been riding since they could walk.

Twenty years ago, Elda sold her car to pay for her first horse. She now co-owns the ranch where her family boards, trains and sells horses. She and her sister also work for a translation company to help pay for costs tied to the sport—from $500 for a dress to $10,000 for a horse.

Tonight, the plan is to run through the routine just one more time.

“Uno!” one escaramuza screams, signaling that her horse will approach the center.

“Dos!” another belts out, to further assist with timing.

The team’s drone captures the scene from above as the horses turn inward from a wide circle, gallop into the center, and perform high speed partner turns before thudding back to the perimeter.

As they practice, a technicolor sunset spreads like a bruise across the enormous sky, after which a bright stadium light illuminates the arena for yet another run-through.

“Alright get to your spots,” Elda barks.

Flowers on the saddle

On competition day, on an 80-acre family ranch in Snelling, charros (male competitors) are running their horses in circles and twirling lassos. A mariachi brass band sets up and vendors prepare to sell tacos and raspado—Mexican-style snow cones—featuring fresh fruit and a bit of picante. Judges, competitors and young children from the dientes de leche (milk teeth) division start to circulate in their finest charrería costumes.

The Flor de Gardenia team gets into costume in a hot, dusty parking lot, with horse trailers doubling as dressing rooms.

Elizabeth Bueno carefully traces her eyelids with waterproof liner, while Crystal Del Toro curls her lashes in the sideview mirror of a Dodge Ram 3500 and Mayra Osmundson, a mother of six, polishes her saddle with leather honey.

The women wriggle into their starchy petticoats, then lift the cherry red dresses over their heads, careful not to let them drag in the dirt. They clip each other’s butterfly bows over low ponytails and fasten one another’s high-necked collars. A cousin familiar with complicated knots ties each woman’s rebozo, a shawl worn around the waist.

Finishing touches include traditional earrings, rosary beads and cameos featuring saints. To comply with the regulations, one escaramuza slips a skin-colored sleeve over a large tattoo on her inner left arm depicting a praying figure, a rose and lettering that reads “stay true.” Osmundson lifts her sombrero onto her head, a photograph of her late father tucked inside.

Some escaramuzas climb up the sides of their trailers and onto their horses, while others are boosted up by family members. They smooth out their dresses and take off trotting to the entrance of the arena, where two female judges from Mexico meet them to inspect their attire.

A judge peers beneath the dresses to check the texture of their petticoats and the colors of their pantaloons, boots and tack. One judge tells Elda two of the team’s quirts, or small whips, are a slightly different shade of bone than the other six. Because the quirts are the same brand, the team gets off with a warning.

As the team’s song El Toro Viejo blares over the sound system, the escaramuzas grip the reins and bolt into the arena, dust flying and spurs clinking.

They gallop in a wide circle, then on Elda’s mark, guide their horses into the center, crossing in front and behind each other at high speed and exploding into partner turns, then disperse back to the wall. Next, four women ride their horses in a small circle in the center as the remaining team members charge through the tight spaces between the circling horses.

“Si señor!” the announcer hoots, and the crowd cheers loudly and cranks matracas.

The routine so far is flawless. But then comes a difficult cross-and-turn combination on the same oily concrete designed for sliding. A horse loses its balance, stumbling first to the right and then to the left. The rider tugs the reins hard and the horse lunges forward, late but still on its feet.

It all happened so quickly that some of the team members didn’t notice. Those who did regain composure during the simpler exercises that follow: a flower pattern and then the abanico, which resembles a fan. During the compuesto, a challenging compound exercise, Elda’s horse balks on the turn. With a dramatic shift of her weight, Elda prevents him from stopping, but it’s not good. The final exercises, a stairway pattern and then another cross, go off smoothly. To the casual spectator, the routine appeared well-executed.

But as the escaramuzas salute the crowd, pat their horses and ride out of the ring, Elda’s solemn expression tells a different story.

The team retreats to an area where families set up picnic tables covered with starry red, white and blue cloths in honor of the Fourth of July, and chat nervously about the errors, wondering what the judges noticed. When Elda returns with their score sheets, her face remains stony.

Although she convinced the judges not to disqualify the exercise in which the horse nearly fell, the team lost 20 points on a flower pattern, which did not match a drawing they had submitted. Their final score, 260, is the lowest they’ve received in recent memory. Flor de Gardenia will have one more try during the U.S. national championships later in the year.

Although disappointed, the women dig into chilaquiles that Elda prepared, crack open Modelo beers and gear up for the next ride.

There are a lot of reasons escaramuzas ride: To make their families proud. To be part of a long-standing tradition. To have a chance to compete in Mexico. But above all that, there’s the simple feeling of being on the saddle, the way the adrenaline surges when woman and horse are one, and nothing else seems to matter.

“You’re in another place,” Elizabeth Bueno says. “You’re in another world.”

Natalie Keyssar is a documentary photographer based in Brooklyn, New York, and is a frequent contributor to National Geographic. See more of her work on her website or by following her on Instagram.

Ashley Harrell is based in Northern California and serves as associate editor for SFGATE covering California’s parks. She also is a Lonely Planet guidebook writer. Follow her on Twitter @AshleyHarrell3.