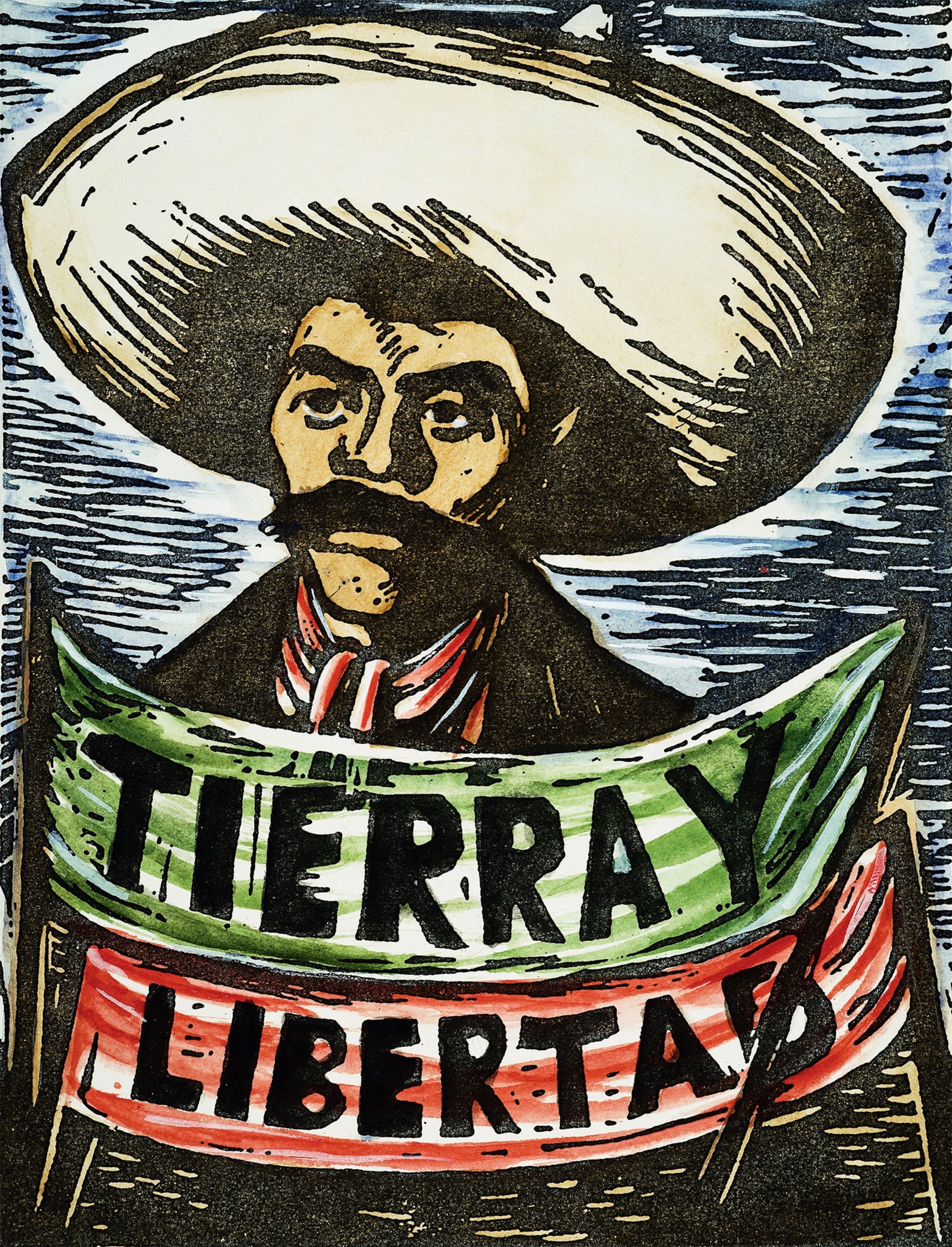

Meet Emiliano Zapata: hero and martyr of the Mexican Revolution

The peasant leader fought for radical agrarian reform in early 20th-century Mexico in the midst of dictators and upheaval. But in 1919, he was betrayed and killed by a traitorous ally.

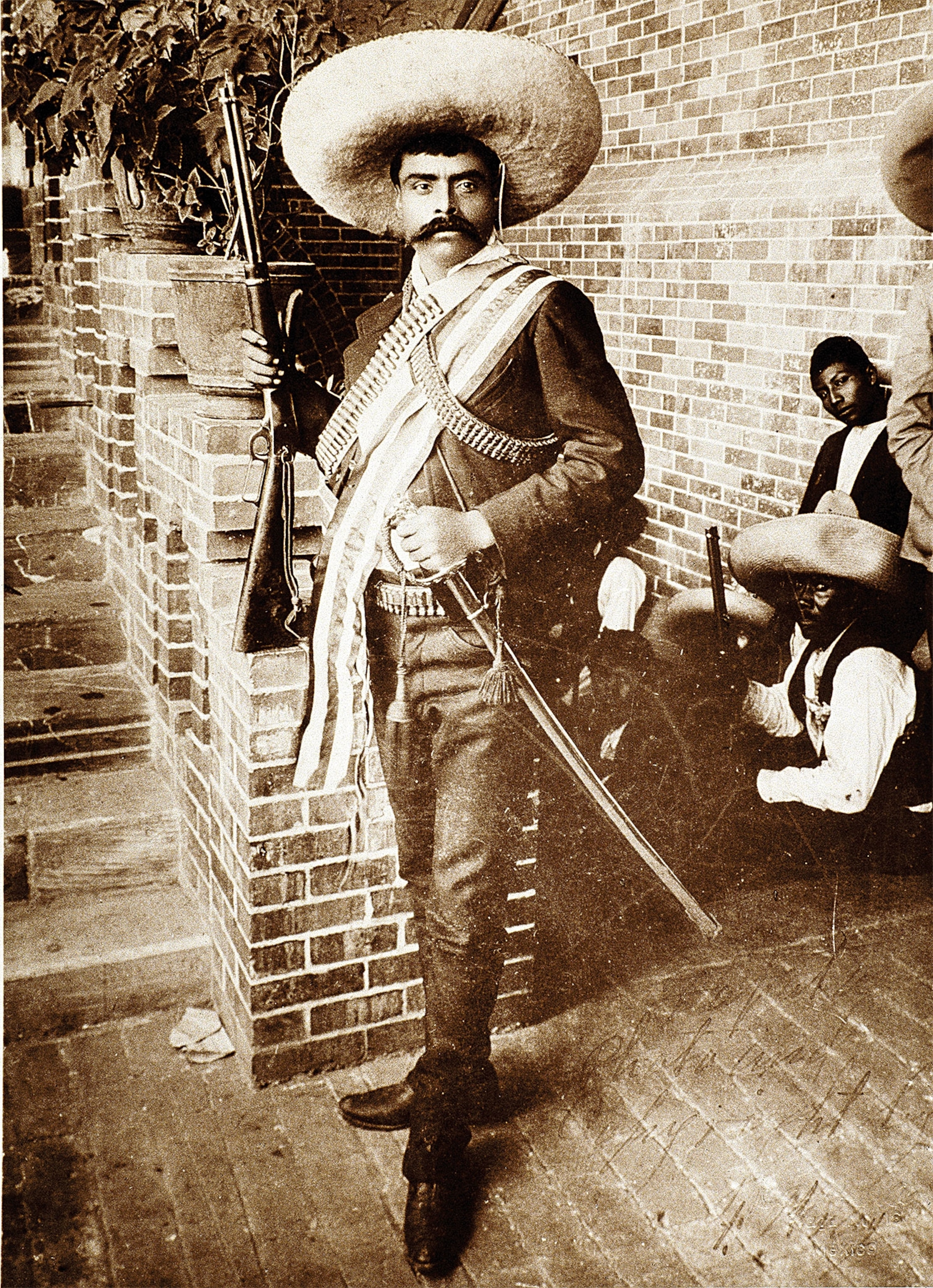

“I’d rather die on my feet than live on my knees,” said Emiliano Zapata, a peasant leader who played a remarkable role in the Mexican Revolution. Zapata was born into an unequal society that became more unjust during his lifetime as the ruling party increased their power and control over the land. As the leader of a powerful agrarian movement in his home state of Morelos, Zapata became a key player and symbol for demolishing the dictatorship and elitist governing practices of the time.

Emiliano Zapata Salazar was born in the village of Anenecuilco in 1879, near the beginning of the Porfiriato, the dictatorial regime President Porfirio Díaz imposed on Mexico for more than a generation. Anenecuilco, with its 400 inhabitants, was a peasant community dating back before Spanish colonization. Its name in Nahuatl (the language of the Aztecs) means “place where water flows” (for the Ayala River) and is reflected in its lush, fertile landscape.

Located in the small but significant state of Morelos, south of Mexico City, Anenecuilco played a crucial role in the great upheavals Mexico experienced in the 19th century: the war of independence against Spain, the internal conflicts between liberals and conservatives, and the French intervention of the 1860s, when Napoleon III’s invading army was defeated by the Liberals, led by Benito Juárez, who would later became Mexico’s president.

(Guns, germs, and horses brought Cortés victory over the mighty Aztec empire.)

Morelos was also an important center of sugar production. Sugarcane cultivation, introduced with the Spanish conquest in the 1500s, flourished in the state’s semitropical valleys. It was in Morelos that Hernán Cortés, the Spanish conquistador who defeated the Aztec Empire, was granted an encomienda by King Charles V—the right to demand forced labor from the Native people. Three centuries later, sugar production was in the hands of wealthy hacienda (large estate) owners. No longer exploiting enslaved Africans after Mexico abolished slavery in 1829, the landowners turned instead to the people of Morelos for labor. They often recruited from communities in Mexico’s south, that had been established since pre-Columbian times. One such village was Anenecuilco.

For generations, relations between the haciendas and the communities had maintained a fragile balance. The local communities were allowed to keep the land they needed for subsistence farming while also working for the hacienda owners. It was not in the latter’s interest to dispossess the peasants, who had already demonstrated their capacity for resistance in the past.

(See stunning images of female equestrians inspired by the Mexican Revolution.)

Landowners versus peasants

This uneasy coexistence collapsed during the Porfiriato as the regime made it easier for haciendas to expand. The landowners controlled local politics, which meant laws that favored their interests and a rural police force to impose those laws. The situation led to particularly acute tensions in Morelos, where long-established communities, such as Anenecuilco, faced grave futures.

The Zapatas were middle-ranking peasants. They were neither well-to-do ranchers nor landless peons, like the exploited laborers who had been forced into involuntary servitude. The Zapatas owned a smallholding including a modest stone and adobe house, had access to the village’s communal lands, and rented other plots from the local hacienda. Emiliano, who in photos typically appears dressed in charro (cowboy) style with narrow pants, silver buttons, and a silk tie, was a farmer, muleteer, and horse trainer. But, like many Morelos peasants, his family suffered when the haciendas expanded. The landowners, taking advantage of sympathetic courts and ambiguity in the title deeds, appropriated private and communal lands and evicted the tenants in favor of peons. Legend says that as a boy of nine, Emiliano found his father crying one day, unable to prevent the loss of his orchard. Emiliano promised his father that he would fight to get the land back and stop the expansion of the haciendas. Twenty years later, with his father dead, Emiliano fulfilled that childhood promise.

(This Belgian princess became empress of Mexico. It all fell apart from there.)

The hour of rebellion

Theoretically, the Porfiriato was a democratic regime, but elections were controlled to ensure that the official candidates won. In 1909 the popular candidate for governor of Morelos was defeated by a rich, young landowner, Pablo Escandón, the official candidate who was educated at an elite school in the United Kingdom. He brushed aside bitter complaints from the local people and garnered resentment. One of his allies infuriated the peasants by saying that if they had no land they could grow their crops in flowerpots.

A year later, when Porfirio Díaz sought his seventh reelection, a vigorous national opposition arose for the first time. When Díaz declared himself the winner, the opposition, in an unprecedented move, did not accept the result. Francisco Madero, a wealthy landowner from northern Mexico and believer in democracy, launched a revolution. To general surprise, his movement gained momentum. Decentralized revolts broke out, first in the north and then in the center of the country.

The rift with Madero

In Morelos, grievances against the regime and the landowning class were intense. In March 1911 Zapata met with his local allies, and together they staged a rebellion in the state that gathered force. Most of Zapata’s followers, known as Zapatistas, were peasants and artisans from the villages (among them were a few hacienda laborers), plus a handful of urban socialists and anarchist radicals. They would be faithful followers of their military and political leader, or caudillo, Zapata, for a decade of struggle. The idea of the Zapatistas as “savage Indians” was sensationalist news cooked up by the capital’s press, as was framing the Zapatistas as bandits.

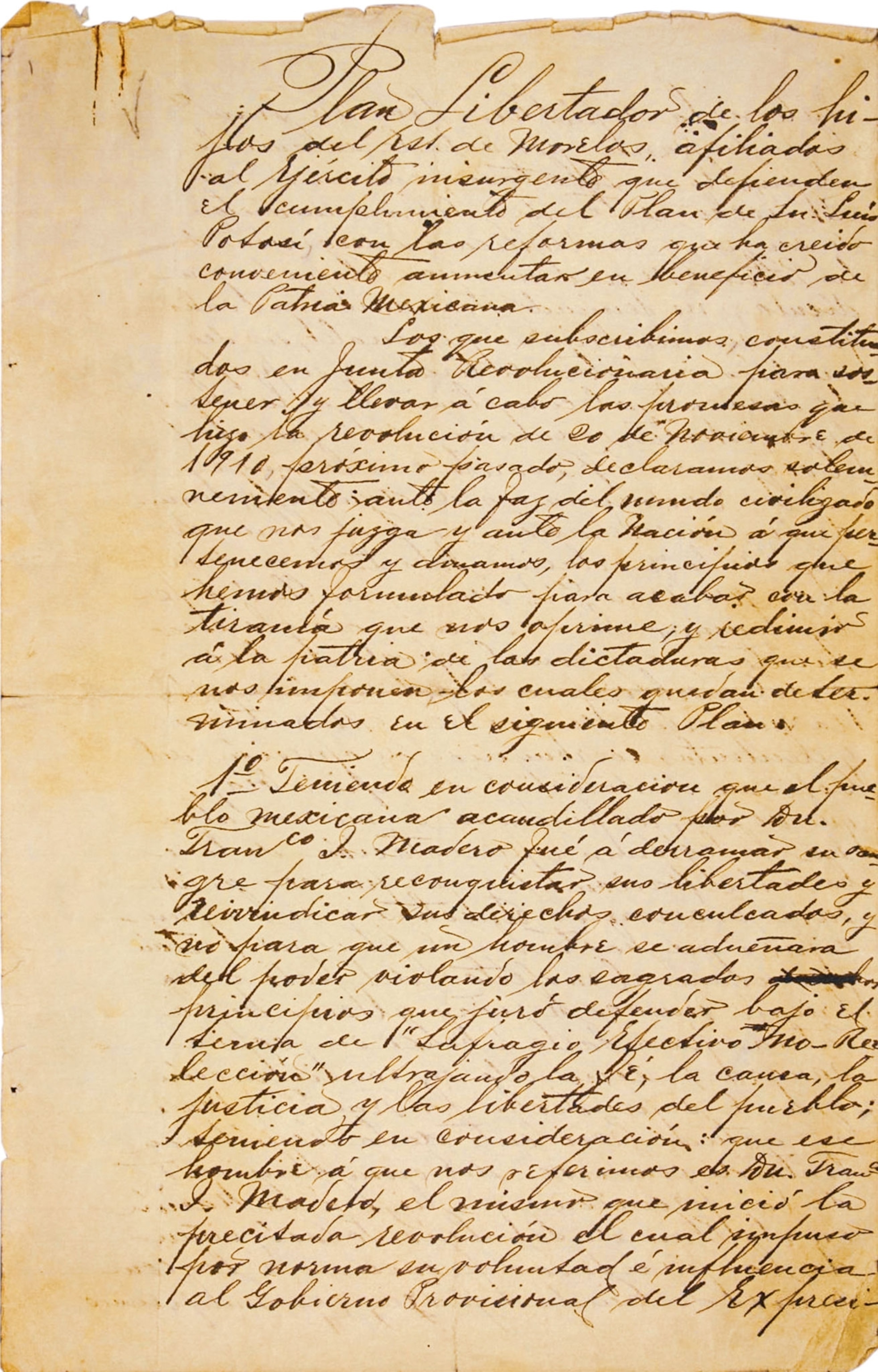

The Zapatista grievances were summarized in simple language in the 1911 Plan of Ayala. The document demanded the restitution of the lands to the people, although it stopped short of requiring total elimination of the haciendas. It was a traditional, patriotic text, full of moral indignation. The Zapatistas may have been old-fashioned, but with that came a long history of popular mobilization. They had horses and firearms, even if they were old shotguns, and the network of extended families who made up their rural communities facilitated revolutionary organization.

In spring 1911, as the rains and planting season approached, the Zapatistas controlled a large part of Morelos. The federal army, meanwhile, was holed up in a couple towns. A similar situation prevailed in northern and central Mexico. Followers of Díaz saw the weakness of their leader and forced him to resign, hoping that by sacrificing the old caudillo they might save their own skins and halt the revolution.

Madero, nominal leader of the revolution, was elected president and began sincerely, if naively, to implement his liberal, democratic program. But Madero was caught between a rock and a hard place. The Porfiristas, considering Madero inept, plotted his downfall, while the more radical revolutionaries, frustrated by the lack of agrarian reform, took up the armed struggle. Zapata was among the latter group. Madero relied increasingly on the federal army, whose numbers and ambition grew.

(Mexico's Independence Day marks the beginning of a decade-long revolution.)

Fight to the end

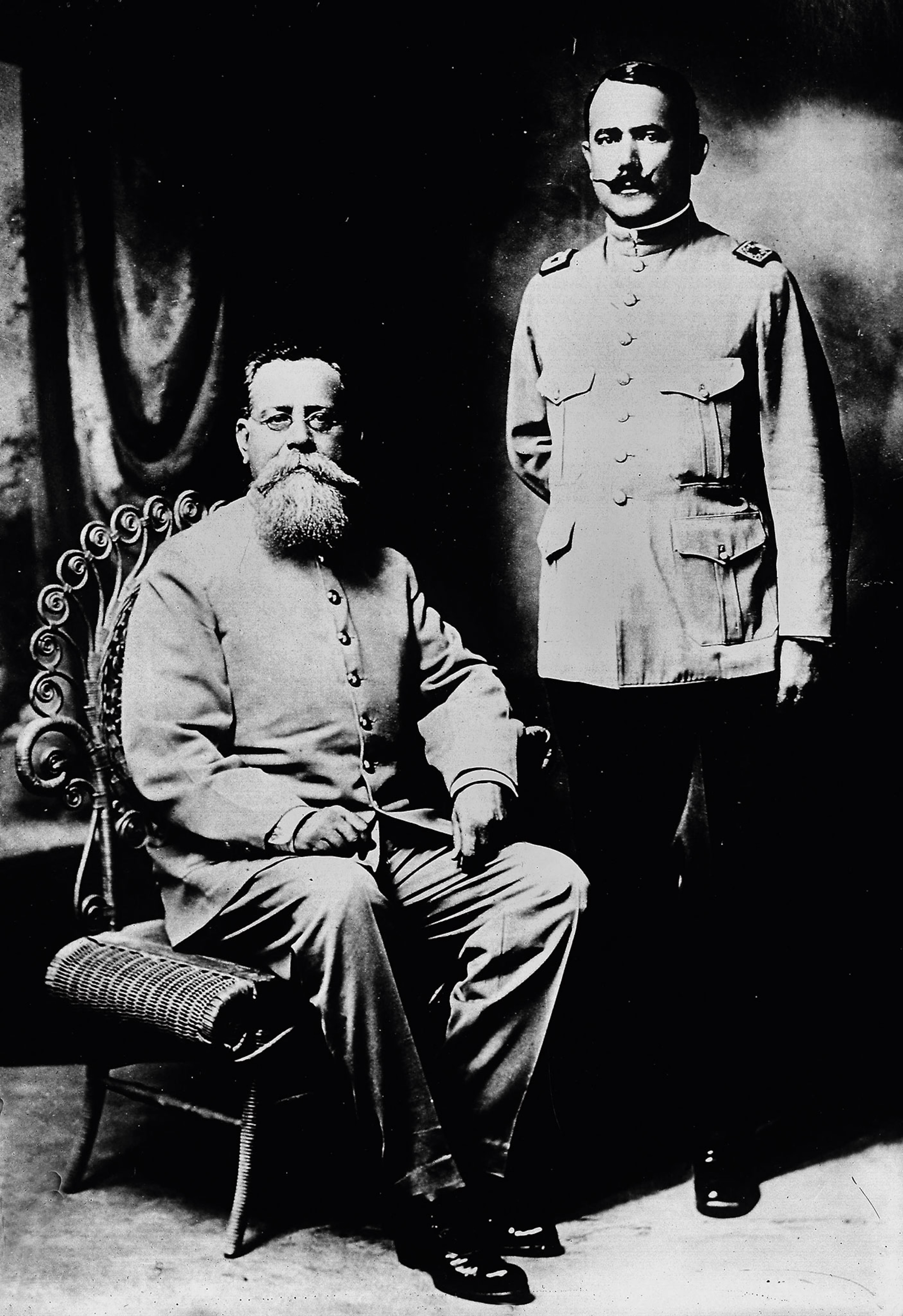

This unstable situation was violently resolved in 1913, when the army overthrew and assassinated Madero, replacing him with Gen. Victoriano Huerta, who had led a brutal campaign against the Zapatistas in Morelos. Upon becoming a military dictator, he employed the same Porfiriato methods nationwide. Rebellions broke out in the north of the country, where Venustiano Carranza, a moderate who had backed Madero, headed a loose constitutionalist coalition. In the center, Zapatismo was gaining strength in Morelos and neighboring states. This civil war was longer and more destructive than the one that had overthrown Díaz. But it ended with the definitive defeat of the federal army and what was left of the old Porfiriato regime.

Meanwhile, the rebels were recruiting large conventional armies, such as the massive Division of the North led by Pancho Villa, the other great popular caudillo of the revolution. Villa fought on the vast northern plains, buying weapons wholesale in the United States, which bordered the territory the Villistas dominated. Zapata, south of the capital, did not have this advantage and, both by preference and necessity, led a genuinely peasant army. The number of Zapatista forces fluctuated according to the requirements of military campaigns and the demands of the agricultural calendar.

While the Villista army was almost professional and undertook long, far-flung campaigns, the Zapatistas retained close contact with the villages and limited their actions to Morelos and the surrounding area, where they carried out extensive agrarian reform. This was both their strength and their weakness. In Morelos they enjoyed deep popular support and were able to resist strongly, but at the national level they were weaker. Suspicious of other revolutionaries, the Zapatistas refused to engage in further collaboration and lacked a coherent national project. For this reason, in 1914, they refused to negotiate with Carranza.

Although Zapatista representatives did participate in national meetings, such as the Aguascalientes Convention in 1914, Zapata and his military chiefs were absent. They left the negotiations to inexperienced urban intellectuals, who riled the other attendees by insisting that the Plan of Ayala should be accepted as the sacred text of the national revolution. Zapata, meanwhile, was wary of politicking and grand gestures. He preferred to stay in Morelos enjoying life in the countryside as a patriarchal caudillo. His was a life of fiestas and bullfights, of aguardiente and homemade cigars, and of fathering 17 children.

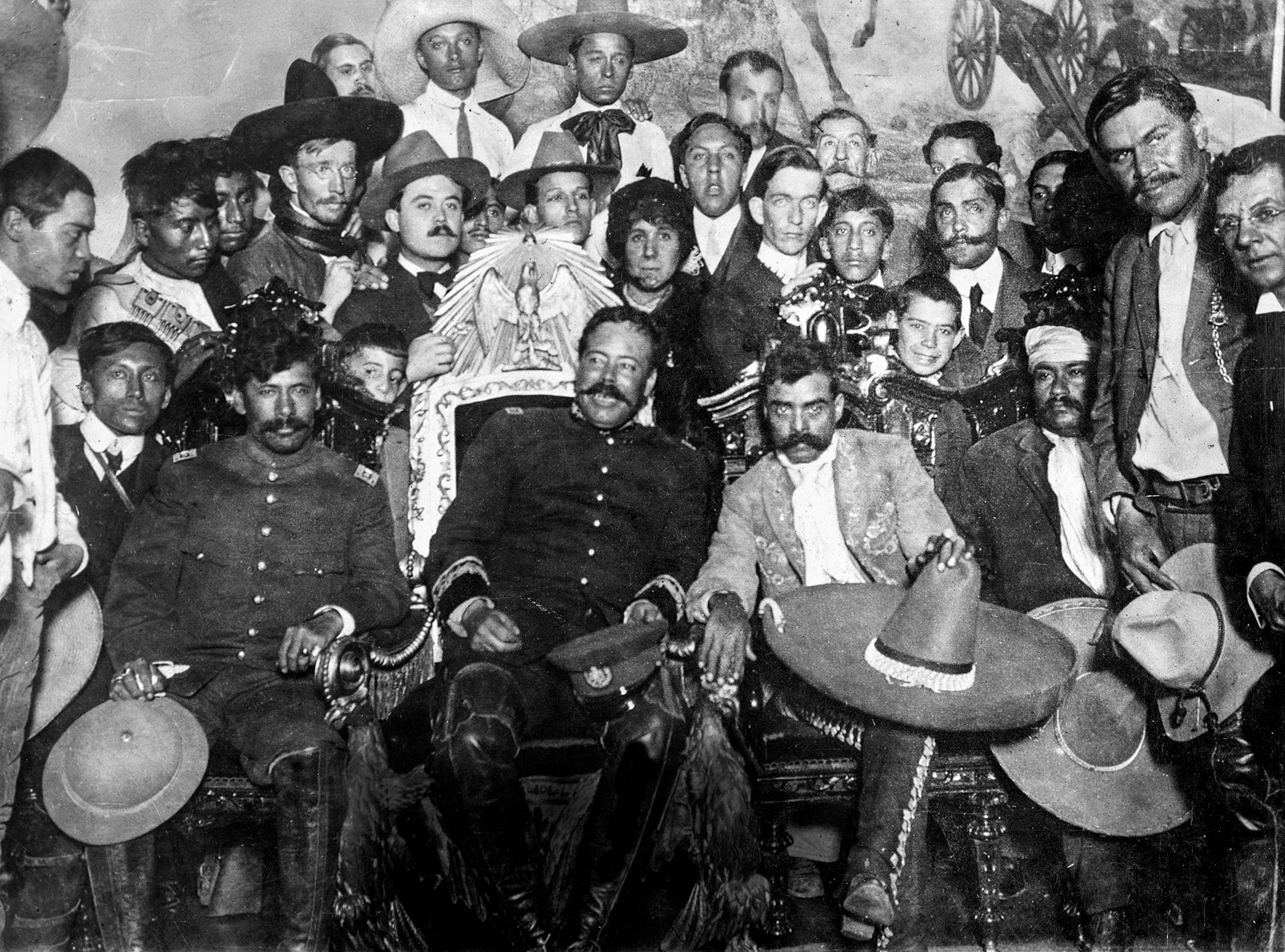

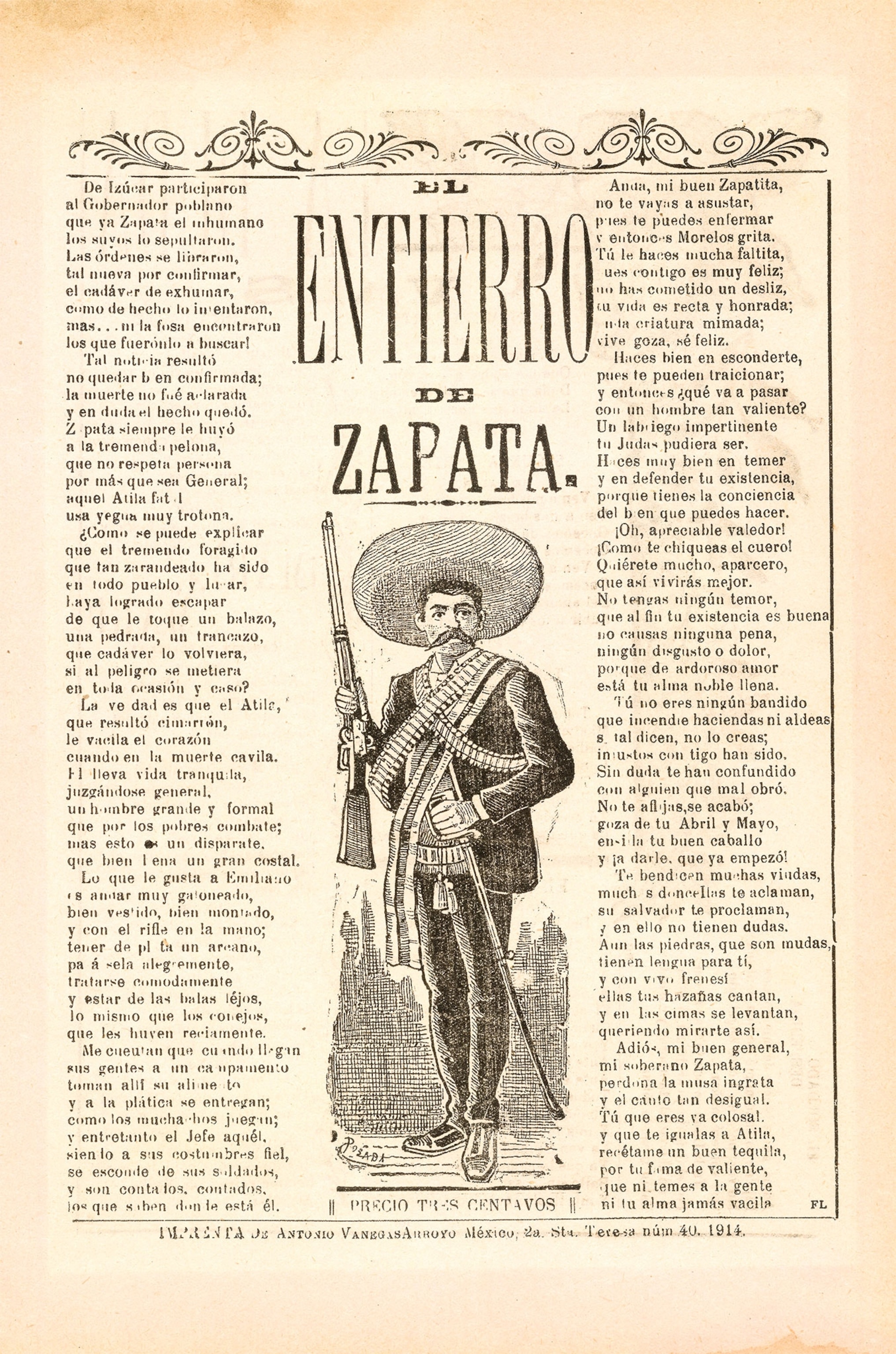

When Villa’s forces entered Mexico City in late 1914, the Zapatistas also paraded in the capital, carrying banners of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The two popular leaders met briefly and amicably. The Zapatistas had little interest in the big city and national politics but were amenable. This put down sensationalist stereotypes in the press about Zapata, dubbed Attila of the South, and his violent followers. Zapata stayed in a modest hotel near the train station, and after a few days he returned to Morelos, to his home, family, and country life.

A meeting of minds

Holding out

Although theoretically Villa and Zapata were allies, their alliance lacked organization and commitment. This would be key as the revolution entered its final stage, a contest between two rival revolutionary coalitions: the Carrancistas and the Villistas. The Villista army, superior in numbers and military reputation, clashed with the Carrancistas under Álvaro Obregón in three major battles fought in Celaya and León during 1915.

Zapata did not take part in these and stayed in Morelos well away from the action. He did not attack the long and vulnerable Carranza supply lines. Obregón triumphed, Villa suffered a decisive defeat, and the Zapatistas found themselves once again in the role of rebels against the central government. But the government was now one that had sprung from a popular movement. It had an army and an ambitious reformist project embodied in the constitution of 1917, the first in Mexican history to include social rights.

The Zapatistas held out for four long years while Morelos suffered war and repression. The revolutionary government wore down the rebels but couldn’t eliminate them, and although Zapata was assassinated in 1919—betrayed and shot dead in an ambush—the rebellion continued. Finally, as the political wheel turned once again, the surviving Zapatistas saw the fruits of their long and bitter struggle.

In 1920 Obregón took power and began the construction of a new nationalist and reformist state. Obregón, who had been an effective general, was also a shrewd politician. He forged a deal with the new Zapatista leader Gildardo Magaña, a pragmatic politician, whereby the Zapatista rebels accepted the new Mexican state in exchange for posts in local government. He also proposed an extensive official land reform that eliminated the sugar haciendas and benefitted the villages.

Zapata’s dream had been achieved, at least in part. Morelos played a pioneering role in the major land distribution project, which, during the 1920s and 1930s, would transform the Mexican countryside. Large haciendas were replaced with ejidos (communal properties that emerged from the agrarian reform). Zapatista veterans played key roles in local politics: Some followed the old goals of the movement, while others, like Zapata’s eldest son, Nicolás, became the caciques (chiefs) of the new order.

The trap

That same day, Guajardo and Zapata met at the Pastor train station. Guajardo presented Zapata with a fine chestnut-colored horse called Ace of Gold. Zapata insisted that Guajardo accompany him to his headquarters to have dinner with the other rebel leaders. But Guajardo said he had to go to the Chinameca estate to make sure that González didn’t seize his ammunition depots. Zapata spent the night in the mountains and on Thursday, April 10, rode to Chinameca with his escort. Outside there were several tents, and in one of them he spoke with Guajardo. Hearing rumors that federal troops were in the area, Zapata went out on patrol with his men. When he returned, around half past one, he met his private secretary, Feliciano Palacios, and they decided to go together to lunch with Guajardo. With only 10 men as escort, Zapata rode Ace of Gold to the hacienda and found military guards waiting at the gate.

The assassination

After the sounding of a bugle (a pre-arranged signal), the soldiers shot Zapata at point-blank range, then charged at his companions. Some fled, while others, including Palacios, were killed on the spot. Guajardo took Zapata’s corpse to Cuautla, from where González telegraphed Carranza. At police headquarters photographs of the corpse were taken, the most famous of which is on the opposite page. It is not clear which day photos were taken. The Mexican press first carried them on April 12, the same day Zapata was buried in the Cuautla cemetery.

From history to legend

Zapata, dead in 1919, saw none of this despite the legend that he survived the ambush to ride his white horse through the sierras of Morelos. Of the many heroes of the revolution, Zapata became the most admired, followed by his ally Villa, who also died young, betrayed in an ambush in 1923. An early, violent death helped his political canonization.

Over time, the revolution that Zapata had helped initiate and define lost its radical, popular character. In the 1940s and 1950s, land reform slowed as industrialization and urbanization gained momentum, and peasant protests revived. A veteran Zapatista, Rubén Jaramillo, led a rebellion in Morelos and was killed by the Mexican Army in 1962.

Thirty years later, when a rebellion of peasants and Indigenous people broke out in the southern state of Chiapas, the rebels called themselves the Zapatista Army of National Liberation. Zapata’s reputation as a national folk hero has certainly endured. In April 2024 the Mexican government unveiled a painting in honor of him. But more than a century after his death, in an urbanized, industrialized, and globalized Mexico, Zapata has ceased to be a historical figure of flesh and blood and has become a symbol detached from his own time and place.

(How César Chávez changed the labor movement—and became an icon.)