Meet the only woman privy to the plot to kill Julius Caesar

Famous ancient Stoic Porcia Cato was a woman of firm political convictions. She helped her husband Brutus see the plot to the very end.

When Julius Caesar seemed increasingly likely to embrace authoritarian rule, two men emerged as the Roman Republic’s fiercest defenders: Cato the Younger, who led resistance to Caesar in the Senate, and his nephew, Marcus Junius Brutus, who led the conspiracy to assassinate Caesar. But there was another key player in the tumultuous events surrounding Caesar’s end: A woman who would come to embody strength under pressure and unwavering loyalty. Her name was Porcia. Daughter of Cato and wife of Brutus, Porcia Catonis (ca 73-43 B.C.) was “the only woman who was privy to the plot,” as the Roman historian Cassius Dio described her.

Porcia’s courage, logical mind, and willingness to sacrifice were celebrated by Roman historians and, centuries later, immortalized in William Shakespeare’s 1599 tragedy, Julius Caesar. Many factors shaped this extraordinary person, but two stand out: the volatile political climate and the teachings of her father.

Growing up Stoic

Much of what is known about Porcia comes largely from Greek historian Plutarch (in his books about Brutus and Cato) and from Cassius Dio’s Roman History, along with mentions in other works. In all ancient references, she is “remembered as the member of Younger Cato’s family who is most committed to her father’s cause,” according to Judith P. Hallett, professor emerita of classics at the University of Maryland and author of Fathers and Daughters in Roman Society: Women and the Elite Family.

Cato put virtue and civic responsibility above all else, values that imprinted on his daughter.

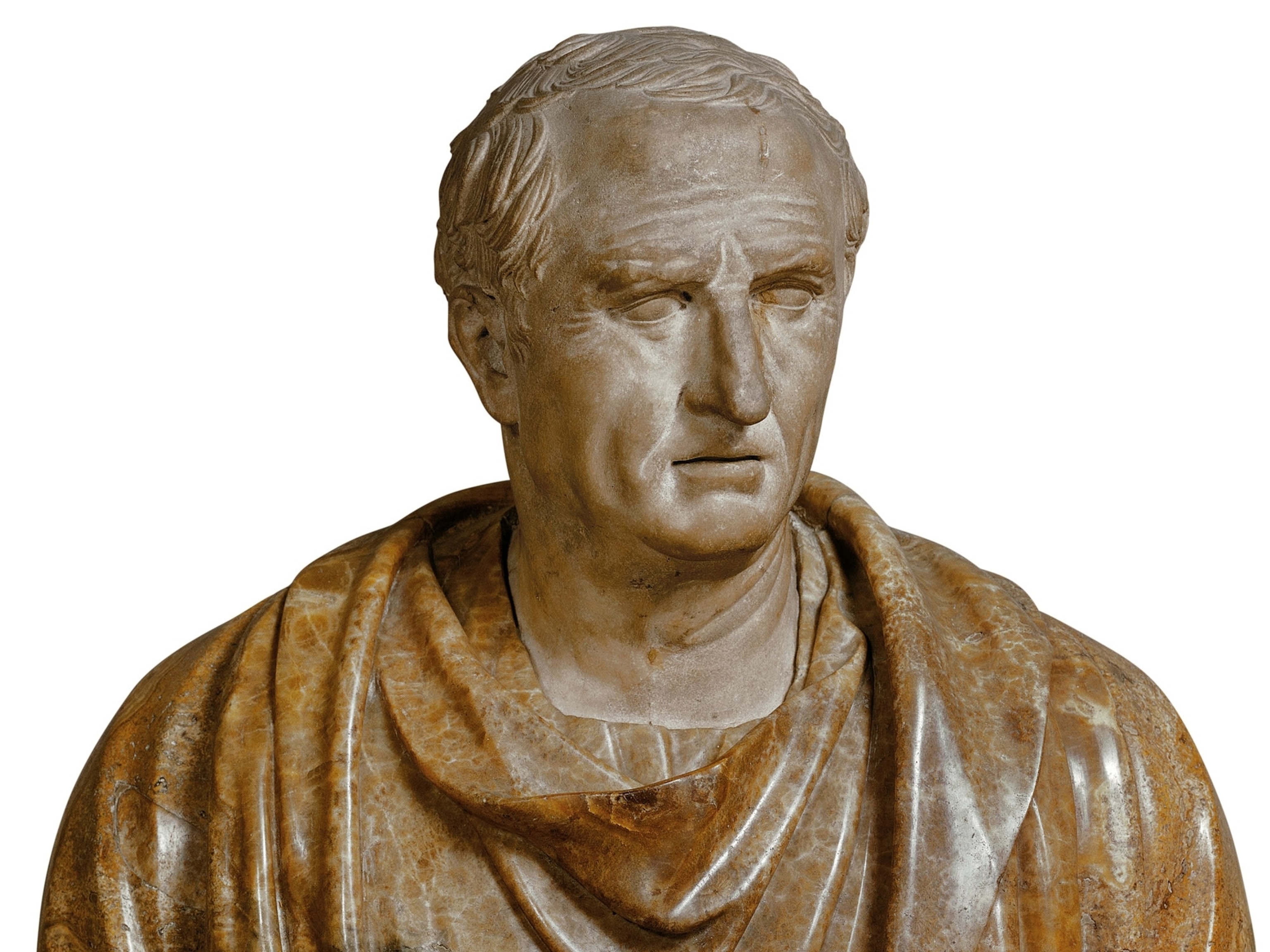

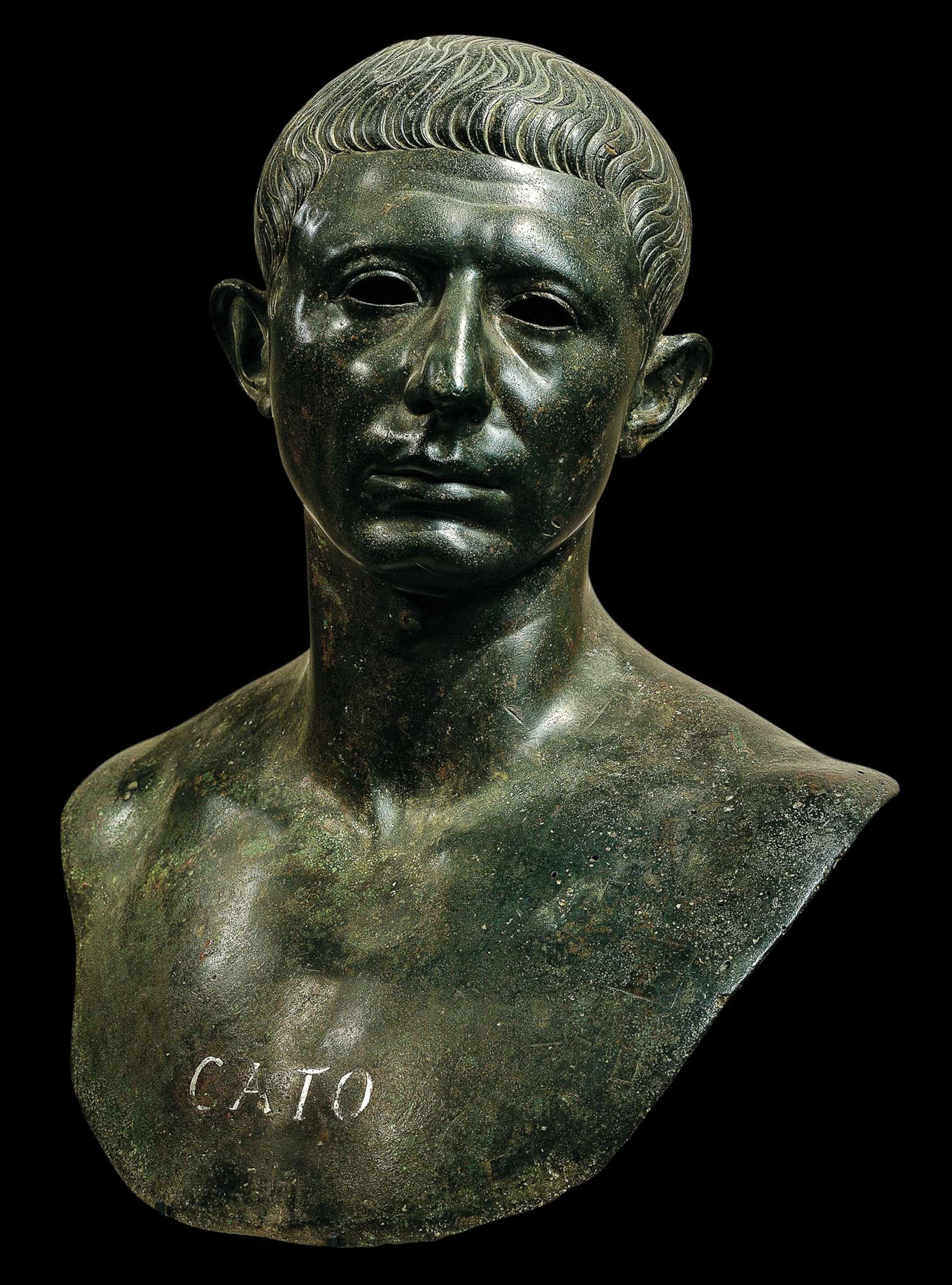

Porcia’s father, Cato the Younger (so named to distinguish him from his great-grandfather Cato the Elder), was an old-guard aristocrat and republican. A devotee of Stoic philosophy, Cato put virtue and civic responsibility above all else, an uncompromising idealism that deeply influenced his daughter.

Early in the second century A.D., Plutarch wrote that Porcia was “addicted to philosophy” and praised her “sober-living and greatness of spirit,” in keeping with the Stoic rejection of luxury and commitment to justice. Based on his depiction, Porcia is often regarded as the first female Stoic.

(What were Marcus Aurelius' rules for life? His self-help classic has the answers.)

Marriages and divorces

As a very young woman, Porcia was wed to a political ally of her father. She and Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus would have two children together before their relationship became complicated by a distinctive Roman practice. In addition to arranged marriages, elite Romans also practiced arranged divorces, ending one match in favor of another that was more advantageous.

Porcia was about 20 when one such proposal came her way. Another of her father’s allies, Quintus Hortensius Hortalus, asked to marry her. The aging, childless widower wanted Porcia as his wife in order to have an heir with her. After she gave birth, he promised to return her to Bibulus.

Bibulus was not a fan of this proposal and refused it. Cato also disliked the idea of breaking his contract with Bibulus. To avoid alienating Hortensius, Cato agreed to divorce his own wife, Marcia, and offered her instead. Hortensius agreed and the plan went ahead. After Hortensius’s death, Cato would remarry Marcia.

Porcia’s high-profile family was deeply involved with the Roman civil war that began in 49 B.C., when Caesar refused to yield his armies and territories to the republic. Rome would split into two factions, one led by Caesar and the other led by Pompey.

The conservative Cato and Bibulus both aligned with Pompey and found themselves on the losing side of the war. Bibulus, leader of Pompey’s fleet on the Adriatic, died of illness around 48 B.C. Cato took his own life in Utica (modern-day Tunisia) when Caesar’s troops won the nearby Battle of Thapsus in 46 B.C.

(Blood and betrayal turned Rome from republic to empire.)

In Rome Porcia watched as Caesar amassed power. Rather than resign herself to a dictatorship, she continued to believe in the old republic. In 45 B.C. she married Marcus Junius Brutus, a onetime ally of Caesar who would famously turn against him. During the war, Brutus sided with Pompey, but in the aftermath of the war, Caesar pardoned him and even made him governor of Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy). Brutus’s sympathies for the old republic, however, had not waned. Marrying Cato’s daughter (and divorcing his wife Claudia to do so) was a way to reaffirm his commitment.

Plans and plots

In the months that followed, Brutus, along with other senators alarmed by Caesar’s ambition, embarked on a plot to assassinate him. Although politics was primarily a male domain in Roman culture, Porcia pledged to aid her husband because of her family’s beliefs. According to Plutarch, she noticed a change in her husband and questioned him. When Brutus wouldn’t answer, she wounded her own thigh with a knife. The act was a plea that her husband show her trust and respect: “Brutus, I am Cato’s daughter, and I was brought into thy house, not, like a mere concubine, to share thy bed and board merely, but to be a partner in thy joys, and a partner in thy troubles.”

"My body ... can keep silence"

Her resolve prompted Brutus to reveal his plan to assassinate Caesar. Moreover, wrote Plutarch, she inspired him to see his plot to the end. “When he saw the wound, Brutus, amazed, and lifting his hands to heaven, prayed that he might succeed in his undertaking and thus show himself a worthy husband of Porcia.”

After Caesar’s death on March 15, 44 B.C., Brutus fled Rome to avoid the wrath of Caesar loyalists, while Porcia remained in the capital. She followed her husband’s fortunes as he fought to defend the republic against Octavian, Caesar’s heir, in alliance with Mark Antony. Finally, Porcia received the news that Brutus had been defeated in the Battle of Philippi (42 B.C.) and, like her father, Cato, had taken his own life.

(Inside the conspiracy to kill Julius Caesar.)

What happened next is not known for certain. The more dramatic ending has a devastated Porcia killing herself, either by swallowing hot coals or inhaling carbon monoxide.

In one version, the poet Martial wrote that Porcia, seeking a weapon to end her life (they had been hidden by attendants), exclaimed: “‘You know not yet that death cannot be denied: I had supposed that my father had taught you this lesson by his fate.’ She spoke, and with eager mouth swallowed the blazing coals.” Plutarch tells a similar story.

Symbol of strength

One key piece of evidence, however, puts Porcia’s suicide in doubt: The Roman statesman and orator Cicero wrote a letter to Brutus in 43 B.C. lamenting Porcia’s death, which means that Porcia died before her husband. Cicero’s words imply that she died of natural causes.

The legend of a violent suicide appeared later but took root in the popular imagination. Plutarch has Brutus say of his wife: “Though she lacks the strength of men, she is as valiant and as active for the good of her country as the best of us.”

A burning question

William Shakespeare in particular found great inspiration in the character of Porcia through his reading of Plutarch. In addition to the historical character of Porcia (spelled Portia) in Julius Caesar, her name also appears in The Merchant of Venice (1596-98), in which it is given to the brilliant woman determined to assert herself in a male world by impersonating a lawyer.

As a symbol of bravery and devotion, Porcia has resonated through history. Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams, the second U.S. president and first U.S. vice president, signed letters to him as Portia, in recognition of the “patriotic sacrifice” of Brutus’s Stoic wife.

(Roman Empress Agrippina was a master strategist. She paid the price for it.)