Blood and betrayal turned Rome from republic to empire

Julius Caesar, Cleopatra, Mark Antony, and Octavian transformed Rome 2,000 years ago through military might, power plays, and political intrigue.

It all started with the Roman Republic, established in 501 B.C. as a model of government that centuries later the fledgling United States and European nations would look toward. Checks and balances on power, impeachment, trial by jury, and the election by citizens of representatives to rule on their behalf are all concepts of Roman law. To understand how this democratic ideal morphed into a dictator-ruling empire, paving the way for the first Roman emperor, it’s imperative to understand who came before: Julius Caesar.

(Julius Caesar came. He saw. He conquered. Here's how Rome celebrated.)

Caesar’s rise to power

A crafty and ambitious Roman general and politician who quickly rose through the ranks of the Republic, Gaius Julius Caesar set his sights on becoming one of the Roman Senate’s two consuls—similar to presidents. In order to get elected, he formed an alliance—the First Triumvirate—with Marcus Licinius Crassus, Rome’s richest man; and Pompey, Rome’s leading general (it was sealed by the marriage between Caesar’s daughter Julia to Pompey). It worked, and with their support, Caesar was elected senior Roman consul in 59 B.C. Together, the trio ensured no step would be taken by the government that did not suit their needs. Caesar enacted land reforms that allotted land to Pompey’s veterans, and altered the tax code, which mollified Crassus’ supporters.

(Crassus was the richest man in Rome. Hands down.)

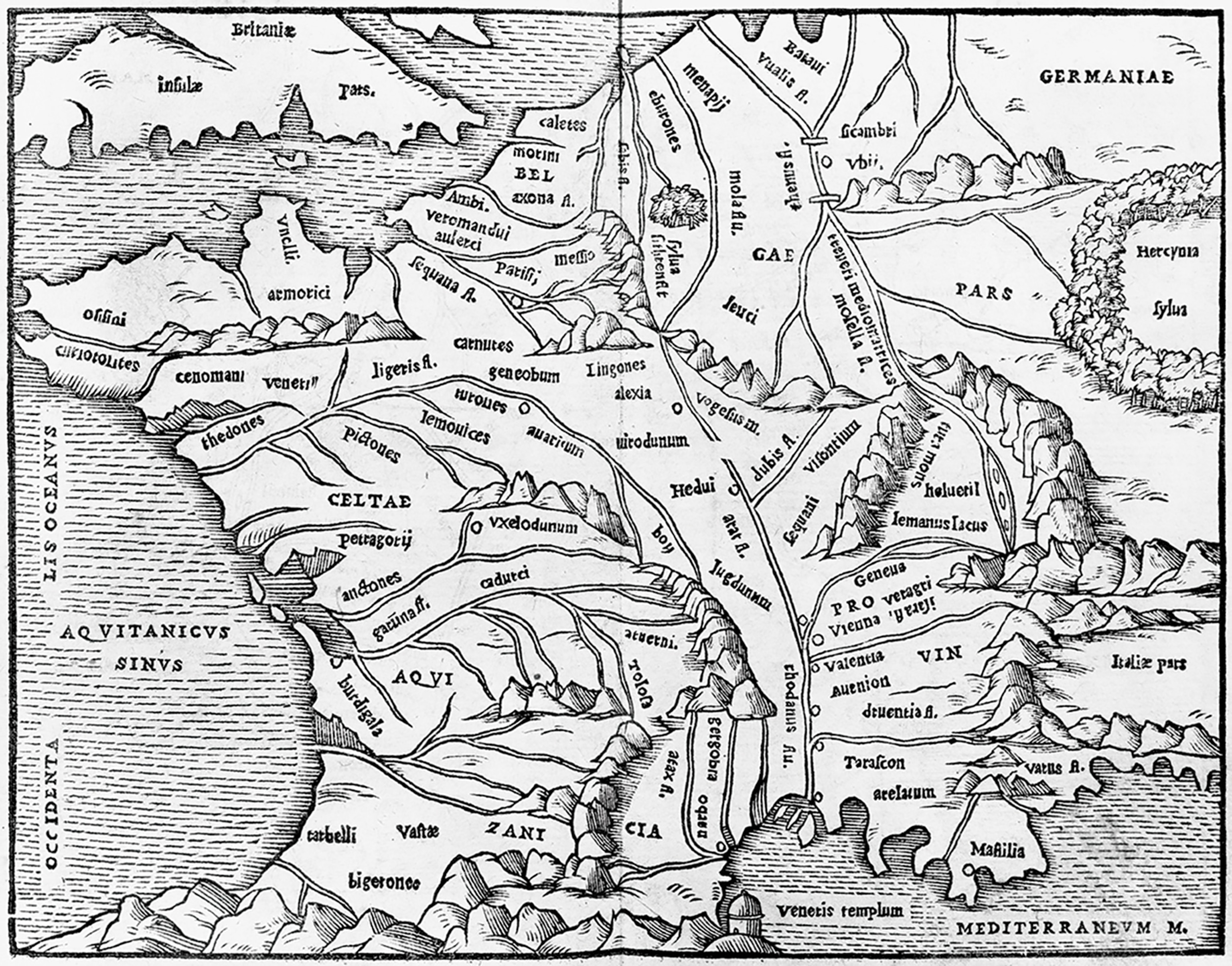

After his consulship ended, Caesar secured the command of the armies and united all of Gaul and invaded Britain, proving himself a ruthless general, while amassing incredible wealth for himself and the Roman treasury. But then catastrophe; his daughter Julia died in 54 B.C. and the following year his ally Crassus was killed in battle, breaking up the powerful triumvirate. Pompey and Caesar, who never really liked each other, clashed.

End of Caesar

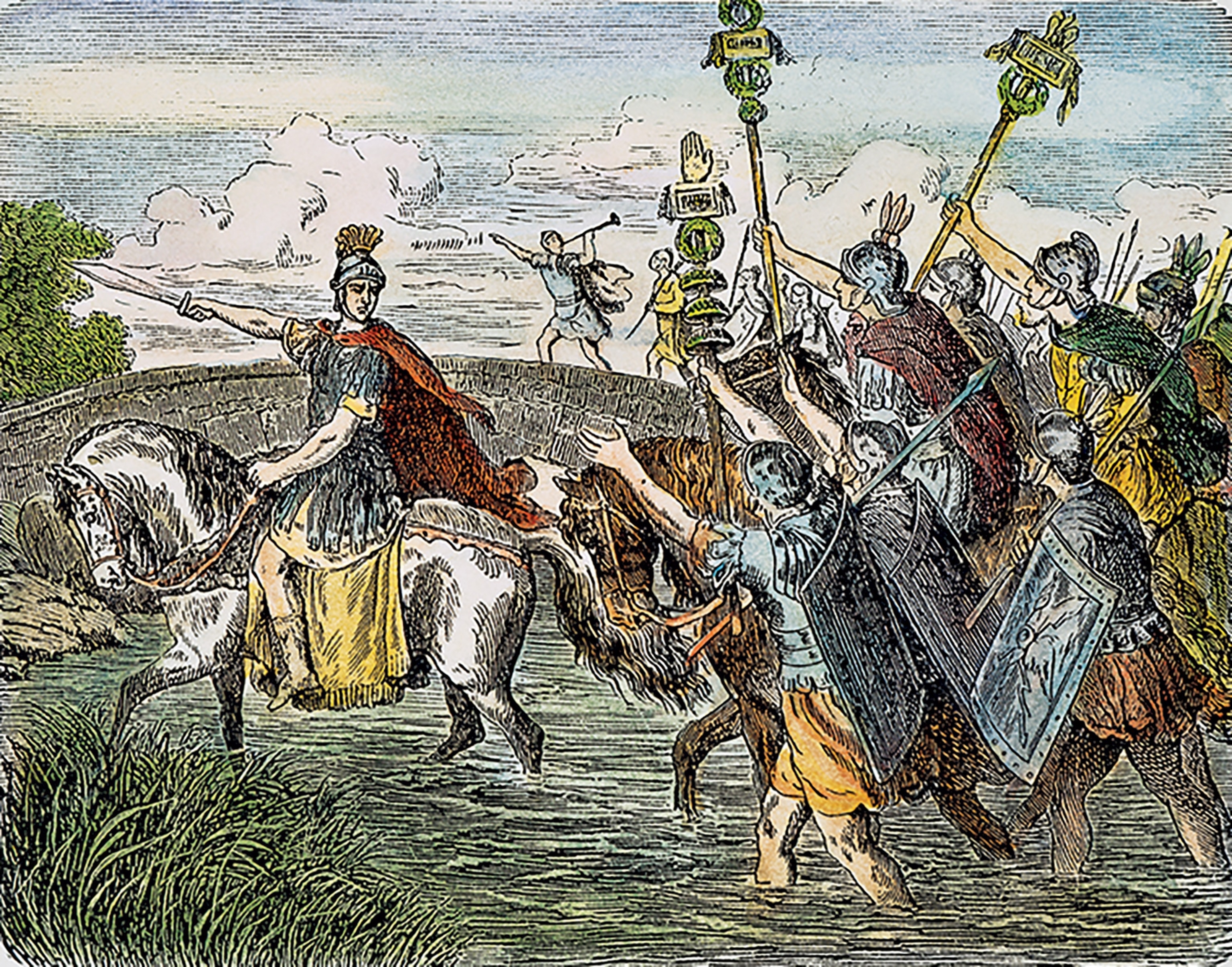

Caesar felt he should return to Rome as consul. The Senate disagreed and backed Pompey, who now saw his former ally as a threat. Caesar sparked a civil war by storming Italy (embarking on his famous crossing of the Rubicon). He quickly overtook Rome, and the people named Caesar dictator. He pursued Pompey and other enemies to Greece, defeating them at Pharsalus in 48 B.C.

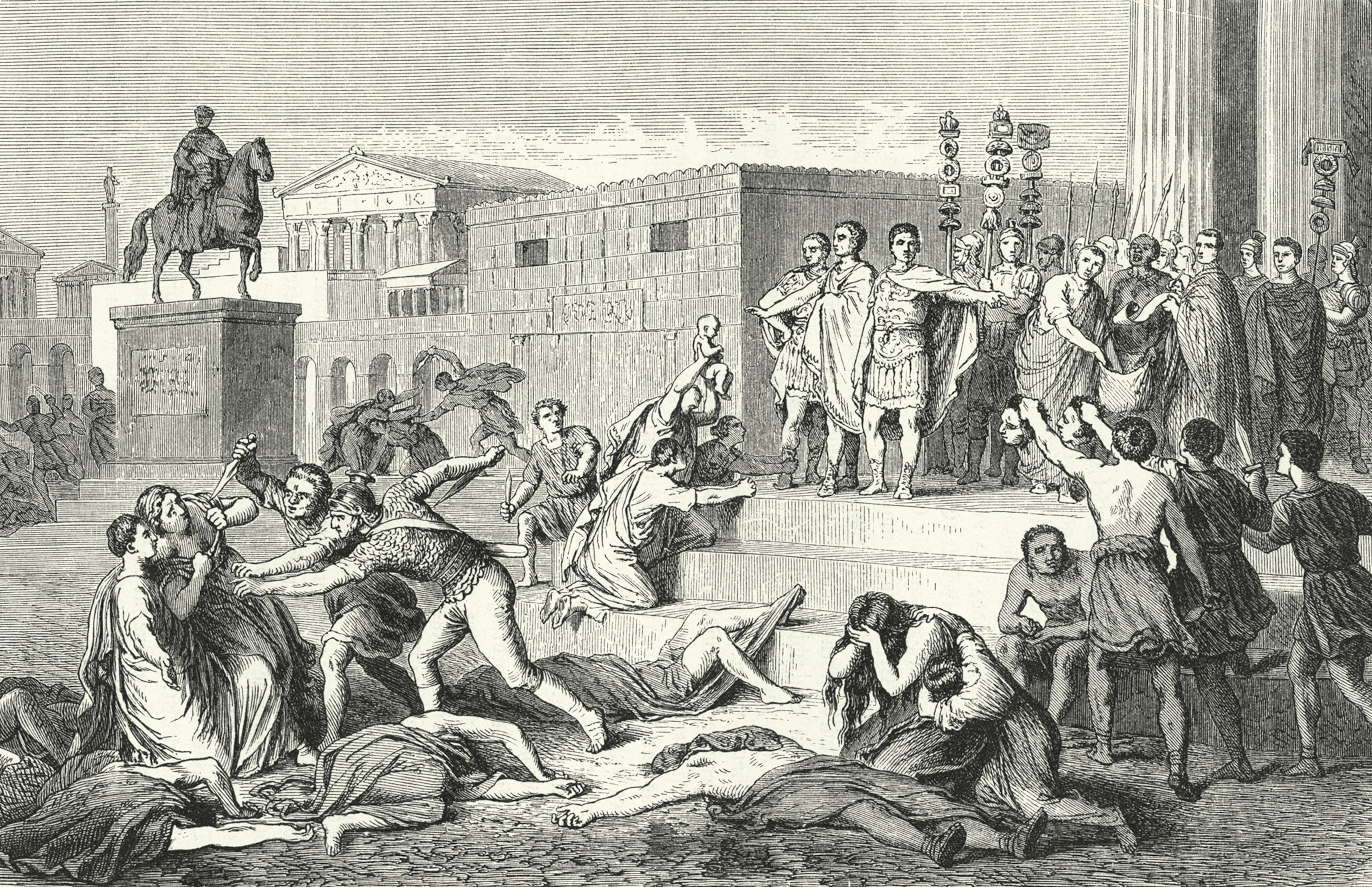

As dictator, a role officially granted for 10 years by the Senate in 46 B.C., Caesar did some good work, including canceling debt, changing the calendar and currency, and granting citizenship to residents of far regions of the Roman Republic. Even so, the façade of the “man of the people” was lost when in 44 B.C. he assumed the post of “dictator for life.” Less than two months later, on the Ides of March in 44 B.C., a mob of Roman senators led by praetor Marcus Junius Brutus stabbed Caesar to death.

Though he was violently deposed, Caesar’s brief rule spelled the end of an era. The republican government would be replaced by a succession of totalitarian emperors: The Roman Empire was officially born. But first, it needed a leader. It would take 13 long years and a series of desperate power struggles before the Roman Republic finally tumbled and the final candidate for emperor donned his triumphal toga.

(Inside the conspiracy to kill Julius Caesar.)

Crossing the Rubicon

The second triumverate

The year after Caesar’s death, in 43 B.C., Octavian, Caesar’s great-nephew and protégé, formed the Second Triumverate with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, a Roman general and statesman, and Mark Antony, a Roman general under Caesar, proclaiming they were “settling the Republic.” It would prove an uneasy alliance in the long term—one that in the end would leave one man standing. But at first, the triumvirate worked together to make and veto laws to their benefit, appoint governors and consuls, and decide judicial cases without appeal, even though the Senate and assemblies still met and elections continued.

In one of their most atrocious acts, they put to death and confiscated the property of some 3,000 patricians, including Cicero, who openly rebuked the triumvirate. The great Roman philosopher was an outspoken critic of Antony, and upon his death, Antony’s wife, Fulvia, took Cicero’s severed head, spat on it, and jabbed his tongue repeatedly with her hairpin, taking postmortem revenge against the famous orator.

(How Cicero's murder ushered in the Roman Empire)

Fall of Lepidus

The triumvirate faced constant threats to their power, including one from the exiled conspirators behind Caesar’s assassination, Brutus and Cassius, who raised an army to overthrow the trio. Antony beat them at Philippi in 42 B.C., absorbing their forces into his own and taking control of Rome’s eastern territories. Believing that Antony deserved to be sole ruler, his wife, Fulvia, and brother, Lucius, mounted a civil war that was put down by Octavian. Tensions rose between the triumvirs.

Meantime, Pompey’s son Sextus, who upheld the cause of his father against Julius Caesar, corralled naval fleets that attacked the triumvirate’s forces in a series of confrontations off the coast of Italy. After beating Sextus, Lepidus demanded more than a third of the credit and more power and prestige. Octavian maneuvered him out of power, leaving Antony his sole opponent.

Antony’s grasp for power

Antony left for Egypt as part of the triumvirs’ agreement to divide the empire. There, he fell for Cleopatra, and reports of their debauched conduct provided fodder to Antony’s enemies as Octavian was proving himself a model Roman: ensuring people had enough to eat, overseeing improvements to the city’s water system, and settling into a stable, conservative marriage with Livia Drusilla. In 32 B.C., Octavian claimed to have proof that Antony was about to move the capital of the republic to Alexandria and declared war.

In response, Antony and Cleopatra tried to invade Italy, but they were blockaded in the Bay of Actium. Octavian’s army was victorious on land and sea, sending the doomed couple fleeing back to Egypt. There, they committed suicide.

(Was Octavian behind the death of Caesar and Cleopatra's "love child"?)

Queen of the Nile

In 47 B.C., when Julius Caesar came to Alexandria, she was in exile, fearful of the ambitions of her brother Ptolemy XIII, so she had herself carried in a sack into her palace, where Caesar was staying. He installed her as queen; they became allies and lovers and she bore him a son, Caesarion.

Determined to protect herself and her son’s future after Caesar’s death, Cleopatra wooed Mark Antony. He was smitten, and the two began an affair that produced three children. Their life together was luxurious. After the loss at Actium, Cleopatra and Antony tried to negotiate with Octavian. They failed, and in 30 B.C., they both committed suicide.

Then there was one

After Actium, Octavian had vanquished his enemies and found himself the last man standing, the sole master of the Roman world. History better remembers Octavian as Caesar Augustus, the name he took in 27 B.C. when he became the first Roman emperor. He had secured his rise to power amid military defeats, civil unrest, shattered alliances, political betrayals, and several close brushes with death. Nevertheless, the Augustan era ushered in an era of peace and prosperity in Rome.

To learn more, check out Atlas of the Roman World. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.