How everyday items peel back the curtain on ancient Rome

Sandals, masks, and other archaeological artifacts provide intimate glimpses into people's lives during Rome's rise, heyday, and fall.

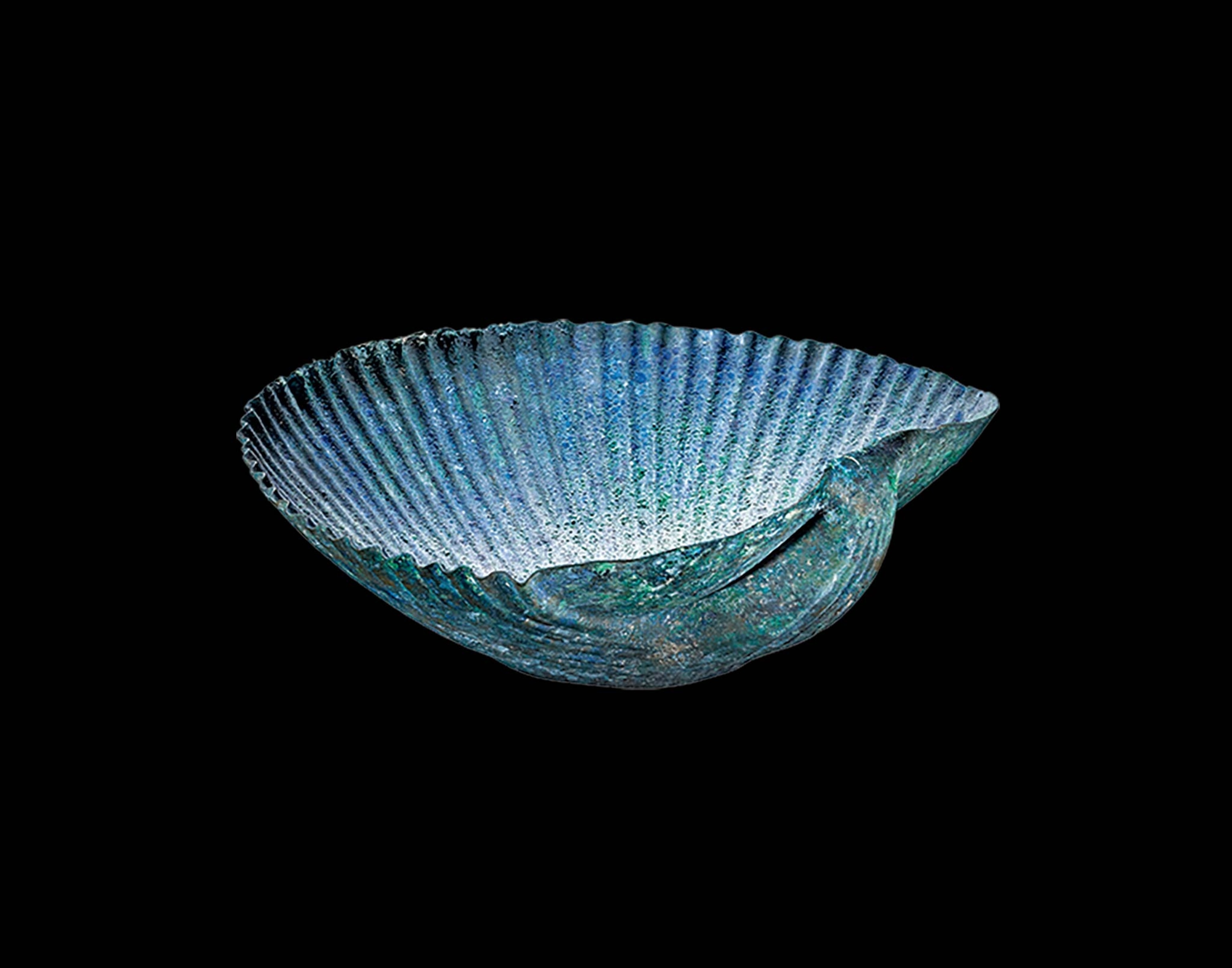

The ancient Romans left behind massive ruins that showcase their engineering and architectural ingenuity, foremost among them Rome’s Coliseum. But archaeologists have also discovered small, everyday items—engraved scarabs, leather soldier sandals, intricately decorated bowls—that speak volumes about their daily lives over 2,700 years ago, from how they worshipped their gods to how they spent their money to how they feasted. Here are some of the most fascinating small-scale finds and the insights they provide into the way the Romans lived.

(Along Hadrian’s Wall, ancient Rome’s temples, towers, and cults come to life.)

Roman gods and goddesses

The Romans were primarily polytheists, with many of their deities inspired by those in Greek mythology. Ancient Romans believed that the 60-plus deities in their pantheon (and plenty of demigods) helped shape the events of their lives on a daily basis. The main divine beings, known as the Capitoline Triad, included Jupiter, the sky god who oversaw all aspects of life; Juno, the chief goddess who was particularly associated with the lives of women; and Minerva, the goddess of wisdom. As Roman power and territory expanded, the Romans added gods and goddesses from vastly different cultures, including Isis from Egypt and Mithras from Persia.

Archaeologists have discovered an abundance of artifacts bearing the images of the Romans’ gods and goddesses, shedding light into this heavenly world.

(Chariot racing stirred up both love and hate in ancient Rome.)

Roman artistry

The Romans are famed for their grandiose marble sculptures, requiring exquisite talent and expertise. One of the most famous is Trajan’s Column in Rome, commissioned by Emperor Trajan after he conquered Dacia (modern-day Romania) during his campaigns from A.D. 101 to 106, and adorned with a spiral frieze that commemorates the Dacia battles. But Roman craftsmen and artisans also created refined everyday pieces that showcase their mastery, including jewelry and musical instruments.

(Romans prized these jewels more than diamonds.)

Most Roman artisans resided in Rome’s working-class neighborhoods along the Tiber’s southern bank. The Travestere neighborhood today retains the essence of an artisan neighborhood, where glass blowers, shoemakers, and marble workers once plied their trade.

The Romans were especially gifted at gold, silver, and other metal work, largely thanks to the influence of their Greek and Etruscan predecessors. Masters passed their skills from father to son, master to apprentice, over centuries.

Archaeologists have discovered some of the most beautiful works providing a peek into everyday Roman life across the empire.

The Roman military

One secret to building the Roman Empire lay in its strong army, required to conquer new lands as well as to secure domestic peace and ensure flourishing trade. By tradition, only landowners could serve in the army. But as the landed class shrank and the Roman army increasingly relied on mercenaries to serve in its auxiliary units, imperial powers created a professional army for which the only requirement was Roman citizenship. Poor Romans rushed to enlist, keen to share in the spoils of conquest.

The Roman army also facilitated cultural assimilation. By serving in the army, residents of conquered lands could also become Roman citizens—and earn all the benefits that came with that, including the rights of property, marriage, voting, and even holding office. However, a soldier had to serve for 25 years before being considered for Roman citizenship.

Artifacts left behind, from weapons to shoes, paint a picture of the lives of Rome’s soldiers.

Coins and currency

The Romans did not invent the use of currency—the Greek world among others had used it for centuries—but they took it to high art. At first, coins were minted from bronze, but as the Roman Empire expanded, war spoils including silver and gold became the basis of the monetary system. The denominations and values changed over the course of centuries, but certain things remained the same, including the sestertii and denarii persisting as some of history’s most famous coins.

(New clues reveal insights into Pompeii's destruction.)

But currency also contributed to Rome’s downfall. In the late second century A.D., Rome experienced a series of economic disasters, including the Antonine plague of A.D. 165, enhanced military spending as Germanic tribes threatened to invade the northern border, and civil wars and social unrest across the empire. Septimius Severus (A.D. 193–211) reduced the amount of silver in each denarius, as imperial powers minted millions of coins to cover expenses. The public confidence in Roman currency waned, igniting inflation. This led to the Imperial Crisis, between A.D. 235 to 284, when more than 20 emperors rose and fell. Inflation sucked the wealth out of 99% of society, leading to mob riots and civil wars. Emperor Diocletian’s solution was to split the empire in two, and the Roman Empire was never the same again.

Archaeologists have unearthed all kinds of different coins that trace this rise and fall.

Food and dining

The Romans excelled at food, using everything from chickpeas to chicken to sea urchins in their lavish dishes. They seasoned their foods with honey, caraway, salt, and pepper, developed wine from grapes, and baked bread and pastries. The most famous ingredient was garum, a fermented fish sauce used to flavor porridge and even as a dessert topping.

(Funky fish guts were the ketchup of ancient Rome.)

And then, of course, there were the famous hours-long feasts, reserved for the elite. Pricey foods such as raw oysters, lobster, rabbit, and wild boar appeared on tables, alongside eye-raising dishes such as parrot tongue stew and stuffed dormouse. The epitome of hedonists, wealthy Roman men ate lying down on chaise longues to help reduce bloating, and they stuffed themselves until they vomited, making room for more.

Archaeologists have uncovered plenty of artifacts that provide a sense of the Roman dining style.

(These 5 secret societies changed the world—from behind closed doors.)

To learn more, check out Atlas of the Roman World. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.