Inside the conspiracy to kill Julius Caesar

Blow-by-blow accounts of the Ides of March spare few details on how Rome's dictator-for-life met a bloody end in 44 B.C.

The first blow fell at noon on March 15, 44 B.C. The conspirators “suddenly bared their daggers and rushed upon him,” writes Nicholas of Damascus, a first-century B.C. historian. “First [Publius] Servilius Casca stabbed him on the left shoulder a little above the collarbone, at which he had aimed but missed through nervousness.”

After Casca’s glancing blow, Julius Caesar “snatched his toga from [Tillius] Cimber, seized Casca’s hand, sprang from his chair, turned around, and hurled Casca with great violence,” according to the Greek historian Appian of Alexandria. Suetonius, a Roman biographer and antiquarian, offers a slightly different account: “Caesar caught Casca’s arm and ran it through with his stylus,” a sharp tool used for writing on wax tablets that could rip through flesh.

“At almost the same instant both cried out,” writes Plutarch, the Greek biographer and historian, describing how Caesar and Casca reacted. Caesar, in Latin, asked, “Accursed Casca, what does thou?” Casca, in Greek, called to his nearby sibling, Gaius, “Brother, help!”

The lethal attack progressed apace. Appian writes that “Cassius wounded [Caesar] in the face, Brutus smote him in the thigh, and Bucolianus between the shoulder-blades.” In response to Servilius Casca’s cry for help, writes Nicholas, his brother Gaius “drove his sword into Caesar’s side.”

The majority of the Roman Senate, not privy to the assassination plot, sat in horrified silence, too scared to flee, though some rushed into the crowd outside. The frenzied scene that unfolded that fateful Ides of March was a blur of blood and gore.

Murderous details

The modern understanding of the attack hinges on the accounts of several ancient sources. Each version ends the same way—with Caesar dead and the future of Rome uncertain—but they differ slightly in their perspectives and analyses.

(Chariot racing stirred up both love and hate in ancient Rome.)

Plutarch, for instance, says the ruler fought back when attacked.“Caesar, hemmed in from all sides, whichever way he turned, confronting blows of weapons aimed at his face and eyes, driven hither and thither like a wild beast, was entangled in the hands of all; for all had to take part in the sacrifice and taste of the slaughter.”

Appian’s account is similar. After being stabbed several times,“[w]ith rage and outcries Caesar turned now upon one and now upon another like a wild animal.”In Suetonius’s version, however, Caesar stopped fighting after the first two blows. With his right hand he pulled his toga up to cover his head; with his left, he loosened its folds so that they dropped down, and kept his legs covered as he fell. Caesar died “uttering not a word but merely a groan at the first stroke.”

Dio Cassius, a Roman historian writing in the third century, says that Caesar was caught off guard by the attack and could not put up a defense.“[B]y reason of their numbers Caesar was unable to say or do anything, but veiling his face, was slain with many wounds.”

“Under the mass of wounds,” Nicholas writes, “[Caesar] fell at the foot of Pompey’s statue. Everyone wanted to seem to have a part in that murder, and there was not one of them who failed to strike his body as it lay there.”

Yet when a forensics expert reconstructed the crime in 2003, he concluded that only five to ten assailants could have actually stabbed Caesar during the fray. It would have been impossible for more to have simultaneously attacked a single person given the logistics and the venue’s dimensions—a space that led to friendly-fire casualties during the attack, with Cassius cutting Brutus’s hand, and Minucius stabbing Rubrius in the thigh.

Caesar himself was stabbed 35 times, in Nicholas’s telling; Appian, Plutarch, and Suetonius put the figure at 23. Suetonius describes how Antistius, a physician, examined the body (in one of the world’s first recorded autopsies) and found that one wound alone had been fatal: “the second one in the breast”—a blow credited to Gaius Casca, in Nicholas’s account.

Once Caesar was dead, Brutus walked to the center of the curia to speak, but no one stayed to listen. The remaining senators fled in terror, fearful that they would be pursued. At that moment it wasn’t clear among the group who was a conspirator, and whether the attack would extend to any of Julius Caesar’s supporters.

Plutarch describes the assassins’ sense of elation as they too left the Senate house, “not like fugitives, but with glad faces and full of confidence.” They hurried to broadcast to the people that Rome was rid of its tyrant. In the suddenly silent curia, only a bloody corpse remained.

Men and motives

By the time Julius Caesar stepped in front of the Senate on that fateful day, the Roman Republic had been ailing for years. Economic inequality, political gridlock, and civil wars had weakened the nearly 500-year-old republic in the century prior to Caesar’s rise.

Yet Caesar was enormously popular with the people of Rome—a successful military leader who defeated his ally turned adversary Pompey after a four-year-long civil war; subdued Egypt and allied with Cleopatra (their love child, Caesarion, aka Ptolemy Caesar, later ruled that country with his mother); and expanded the re- public to include parts of modern-day Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, Spain, and France. He also passed laws (over the Senate’s objection) that helped the poor and was a beloved author who wrote frequently about his travels, theories, and political philosophy.

Many members of the Senate—a group of appointed (not elected) political leaders that included the Optimates, a small elite conservative group of Caesar’s enemies that had backed Pompey—resented Caesar’s popularity and perceived arrogance.

(In ancient Rome, citizenship was the path to power.)

As they saw it, Caesar’s increasingly autocratic reign threatened the republic. He frequently bypassed the Senate on deciding important matters, controlled the treasury, and bought the personal loyalty of the army by pledging to give retiring soldiers public land as property. He stamped his image on coins, reserved the right to accept or reject election results for magistrate and other lower offices, and—perhaps worst of all—was rumored to be ready to declare himself king.

Rome had been stridently anti-monarchist since 509 B.C., when Lucius Tarquinius Superbus was overthrown, and prided itself greatly on its liberty. To be accused of coveting a throne was an egregious affront. Opponents worried that Caesar wanted to restore the monarchy, with himself in control. Though he had publicly refused a symbolic golden crown offered to him at the pastoral Lupercalia festival by his cousin and close ally Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony), his behavior seemed to corroborate this thinking. He had installed his friends in positions of power, placed his statues in temples, and reacted with fury when a diadem placed on one of them was removed. He also wore the high red boots of Italian kings and donned triumphal dress (symbolizing martial victory) whenever he liked.

Even his habit of granting clemency to opponents could be seen as a reflection of sovereign thinking: To show mercy, one had to be in a position to have power over someone else—one had to be a king.

Such was the situation in 44 B.C. After his stunning victories at the battles of Pharsalus, Thapsus, and Munda, between 48 and 45 B.C., Caesar had acted in a way that was largely unprecedented among the victors of civil wars: He let the losers live, because he hoped to join their power with his.

It was in this way that Brutus, who’d fought against Caesar under Pompey, and Cassius, who had commanded Pompey’s fleet against Caesar at Pharsalus, were pardoned rather than executed. Caesar appointed both men to the position of praetor in 44 B.C.—a benevolence that riled many. They saw the dictator’s clemency as both humiliating and arbitrary, running contrary to the principles of law—the mark of a tyrant.

Once Caesar became dictator-for-life—a magistracy that placed the maximum civil and military powers in his hands—the political career of every Roman rested with him. It was a bitter affront to the Optimates who had been pardoned by Caesar but now found themselves dependent on his whims.

These officials decided to strike the ultimate blow against his power. All of the assassins on the Ides of March belonged to Caesar’s inner circle—enemies he had forgiven and friends he had promoted. What brought these “liberators” together was a fear that the concentration of absolute power in a single man threatened the republic’s democratic institutions.

dangerous ambitions

(200,000 miles of Roman roads provided the framework for empire.)

The conspirators

At least 60 people, and perhaps more than 80, were involved in the plot against Caesar. The mastermind of the conspiracy was Cassius, who understood that he needed to collaborate with someone who would lend political gravitas to a future attack, raising it above the level of petty personal revenge. He chose his brother-in-law Marcus Junius Brutus, a respected Optimate. His family claimed to descend, by paternal line, from Lucius Junius Brutus, who was said to have founded the Roman Republic.

With Cassius planning in the background and Brutus acting as the figurehead, the alliance was forged. Among the latter group, two men stand out: Gaius Trebonius and Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, both generals who had fought alongside Caesar in Gaul and the civil war. The latter was a distant cousin of Brutus and a close friend of Caesar.

Plutarch recounts that a year before, after Caesar’s victory in Munda, Trebonius had sounded out Mark Antony about the possibility of joining an assassination. Nothing more is known of the plot except that Mark Antony declined to join it, yet he also failed to inform Caesar that a scheme was being hatched against him.

(Scholars struggle to determine what Caesar actually looked like.)

When Trebonius told the plotters that Mark Antony would not participate, they agitated to kill the Roman general as well, but Brutus objected. He believed that getting rid of Caesar was an act of universal justice, while killing Mark Antony would be seen as a partisan act. Instead, they decided that on the day of the assassination, they would keep Mark Antony distracted outside the Senate—he was a senator as well as a general—in case he tried to come to Caesar’s aid during the attack.

Caesar had been due to leave for a long campaign against the Parthians two days after the Ides of March—“Ides” was the name given to the middle day of each month—but had summoned the Senate to meet once more before he left. According to Suetonius, it was rumored that at this meeting a proposal would be made to proclaim Caesar king of the non-Italian provinces, a proposal the conspirators did not want to approve. They also knew that once Caesar left Rome with his legions, he would be out of their reach.

According to Cicero—a senator at the time, and a very well-informed one—the Senate meeting had actually been called to finalize a decision as to who would replace Caesar as consul when he left Rome. That year, Caesar and Mark Antony were joint consuls; with Caesar gone, Mark Antony and the new appointee would constitute the highest authority in Rome.

In some ways, the stage was set for them. Though Caesar had heard rumors of assassination plots against him (some of which expressly mentioned Brutus), he had decided to ignore them in the belief that Brutus and others would never act against him out of fear that a new civil war might be unleashed if he were to die.

Caesar had also recently dismissed his official escort of bodyguards, after the senators vowed to protect him with their own lives in a pledge of political loyalty. Yet he would be far from unprotected on the Ides. Twenty-four lictors— in charge of safeguarding the magistrates—walked before him wherever he went. He was also accompanied around the city by friends and stalwart followers—some seeking favors, others just a glimpse of the great man.

After considering several options, the conspirators decided to make their move during the Senate session, where Caesar’s entourage would be reduced (only senators could attend) and the emperor would be unarmed (weapons were forbidden inside the Senate, so the conspirators had to carry theirs carefully concealed).

Hired Muscle

Dreams and omens

On the night of March 14-15, Caesar’s wife of 15 years, Calpurnia, had vivid nightmares in which she saw her husband covered in blood. The next morning she begged him not to go to the Senate.

The emperor claimed not to be superstitious, but he was disturbed by his wife’s visions—and by his own dreams that night of rising above the clouds, leaving Rome at his feet, trembling as Jupiter took him by the hand—so in the morning he took her dream seriously. He ordered several animal sacrifices to discern the future.

All the omens were unfavorable. A month earlier, a soothsayer, or haruspex, named Spurinna had warned Caesar of the peril before him. On February 15, writes Suetonius, Spurinna had “read” sacrificed animal entrails to mean that Caesar faced “danger, which would not come later than the Ides of March.”

On top of everything else, Caesar was physically ailing. According to Nicholas of Damascus, Caesar’s physicians tried to stop him from going to the Senate that day “on account of vertigoes to which he was sometimes subject, and from which he was at that time suffering.” (The long-held theory is that Caesar had epilepsy. It is also possible he suffered a mini stroke.) As the Ides dawned, Caesar felt exhausted and nauseated. According to Suetonius, he decided to stay home and send Mark Antony to the Senate to dissolve the session.

Yet at that critical moment, Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus appeared and convinced his “friend” Caesar to go to the Senate as planned, telling the dictator he would appear ridiculous if he changed his plans because of his wife’s dream. If the dictator felt genuinely ill, he could avoid offending the senators by showing up briefly at the Senate and then postponing the session.

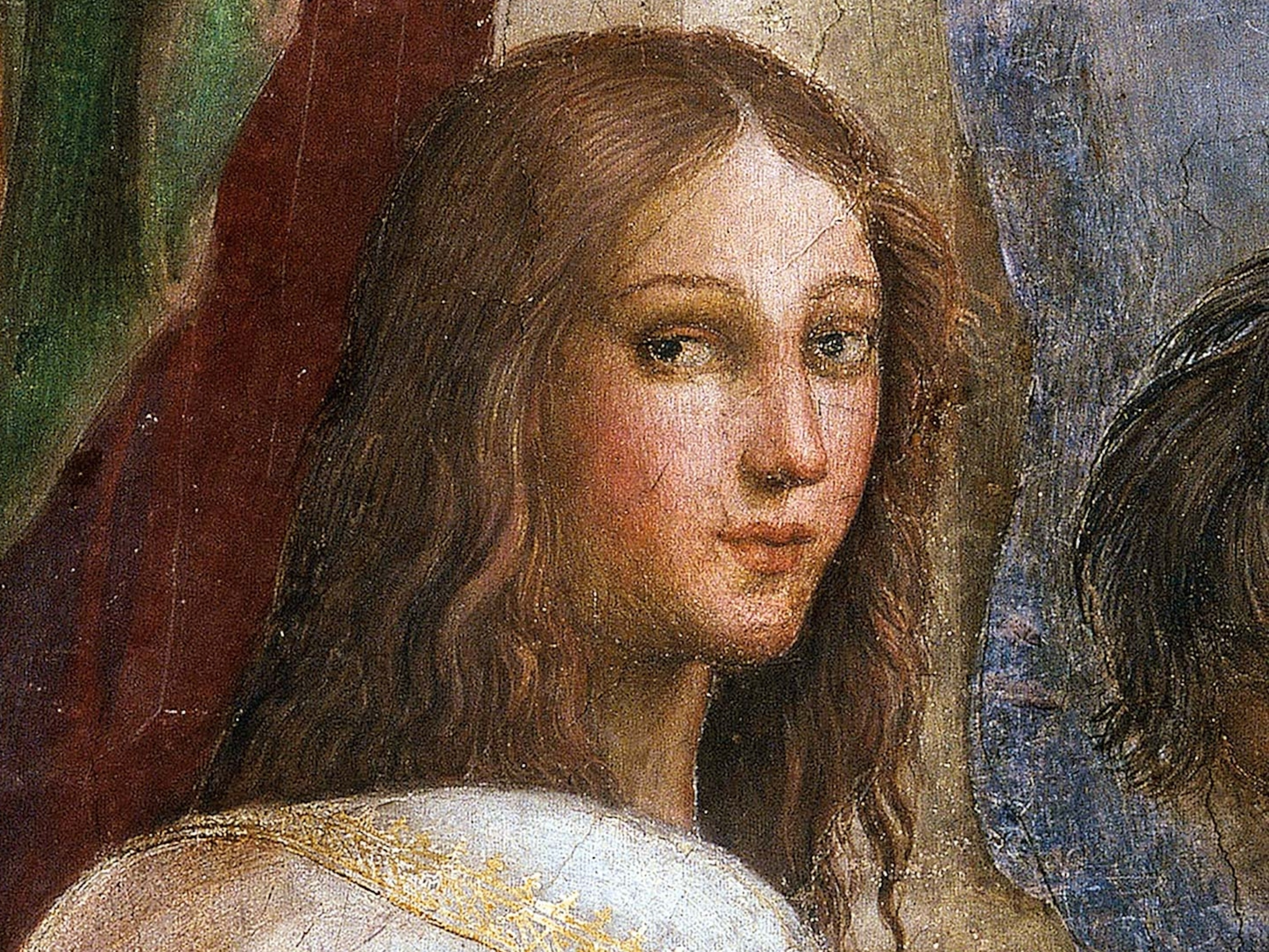

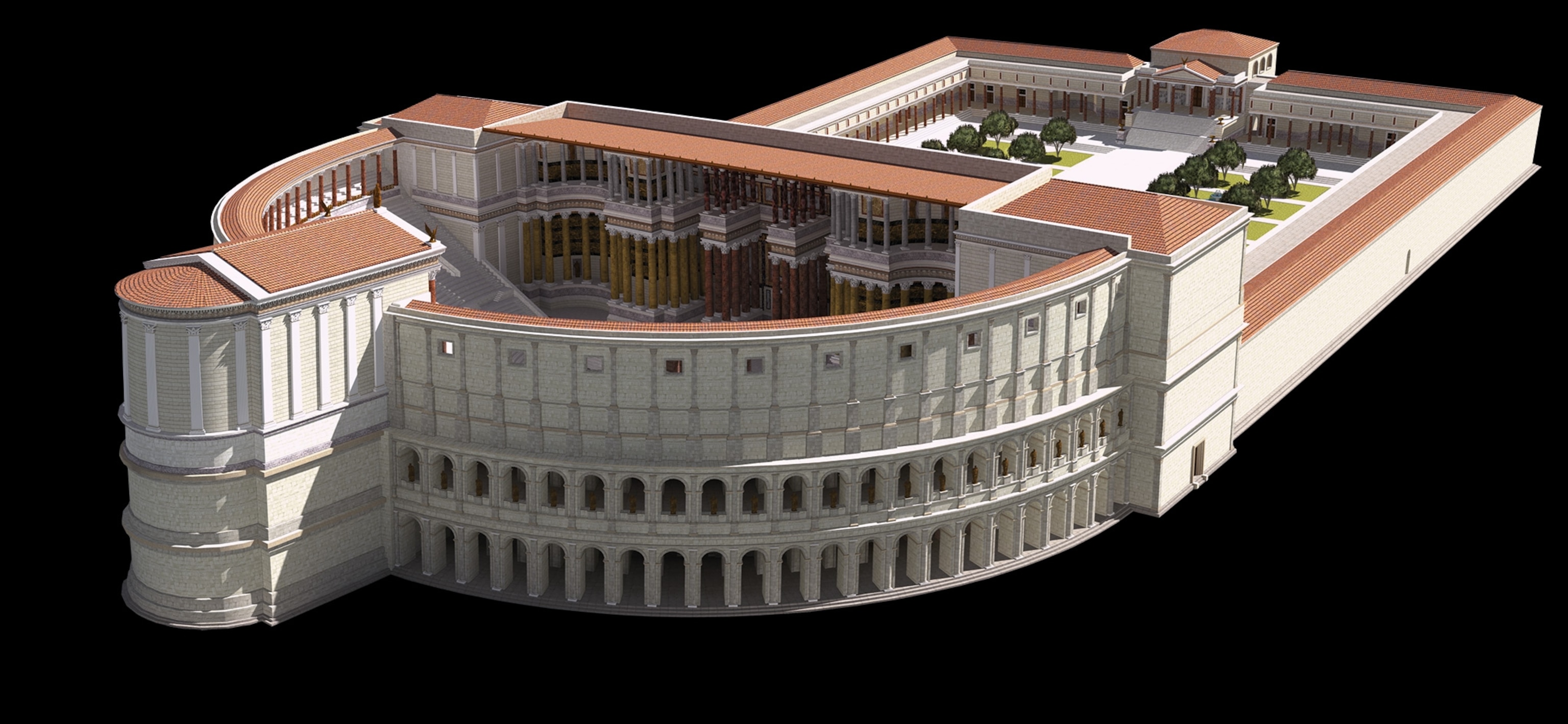

Decimus Brutus’s reasoning worked, and Caesar left his house at 11 a.m. in a litter borne by four slaves, preceded by the lictors. Caesar was headed for the Theater of Pompey, a huge complex built by his rival on the outskirts of Rome. Within it was the curia (Senate house), where the meeting would take place.

On the way, a crowd surrounded the litter and overwhelmed Caesar with petitions. Amid the noise, Caesar overlooked a note that someone handed him warning him of the plot. It may have been proffered by Artemidorus of Damascus, a Greek teacher from Brutus’s circle. According to Nicholas of Damascus, the note was found near Caesar’s corpse among the other papers.

Plutarch wrote “[the conspirators] all hastened to the portico of Pompey and waited there, expecting that Caesar would straightway come to the meeting.” Since it was forbidden to carry arms in the Senate, Brutus’s dagger was hidden under his robe. Other senators concealed their weapons in the document boxes that young slaves, called capsarii, had brought into the compound.

Caesar arrived. As he walked through the door, the senators rose. The chamber was not much bigger than a modern tennis court, and at least 200 men had to be present to comprise the quorum. There was little room to maneuver.

The attack

Not all the conspirators were members of the Senate, and it’s not clear how many of the standing senators wished to see Caesar dead. In front of their seats rose the platform from which Caesar would preside over the session from a golden throne. The conspirators hurried to gather around the throne.

As soon as Caesar was seated—and while the rest of the senators were still standing as a show of respect—the assassins, writes Plutarch, “surrounded him in a body, putting forward Tillius Cimber of their number with a plea on behalf of his brother, who was in exile. The others all joined in his pleas, and clasping Caesar’s hand, kissed his breast and his head.”

At first Caesar brushed off the requests. But when the senators would not let him go, he tried to get up by force. It was then that Tillius, who may have been kneeling before Caesar, grasped his toga at the shoulders in a gesture of supplication. This prevented Caesar from standing up and left his neck exposed. According to Suetonius, Caesar then shouted, “Why, this is violence!”

Appian says Tillius then shouted, “What are you waiting for?”: The answer, of course, was nothing. The rest, as they say, was history.

Human Sacrifice?

(This Roman emperor believed he was a god. He was assassinated for it.)

Aftermath

After Caesar’s death, Mark Antony staged a grand funeral for Caesar. The dictator’s popularity was such that a riot developed, leading to Caesar’s impromptu cremation in the Forum. Some of the assassins, including Brutus and Cassius, took this as a cue to leave Rome, though neither gave up their official positions. The remaining assassins put a positive spin on the events, celebrating it as an end to tyranny.

An amnesty was negotiated—through a Senate agreement to ratify all of Caesar’s decisions. A new coin was minted, showing two daggers and the pileus, the cap of liberty worn by freed Roman slaves, with the date shown as the Ides of March. It was a celebration of liberty, according to historian Mary Beard, that resonated in Rome much like Bastille Day does in modern France.

Ultimately, the death of Julius Caesar had the opposite impact of what the assassins had hoped. The daggers they thrust into him that March day dealt a fatal blow to the already wounded Roman Republic and paved the way for empire. Much of the public turned against the assassins, and civil wars ensued. Popular sentiment swung back toward Caesar. A comet, visible during the day for a week, appeared in the sky during the games held in his honor—a sure sign that he was becoming divine. Within two years, in fact, he would be fully deified.

Caesar’s death opened the way for his 19-year-old heir, and adoptive son, Octavian to emerge as Rome’s first de facto emperor (the future Augustus). Octavian would spend the next few years hunting down Caesar’s murderers: the ringleaders Brutus and Cassius fell in 42 B.C., and the last one would perish eight years later.