Was Nero really a monster?

Rome experienced some of its greatest economic and cultural dynamism under Nero's rule, and yet he's called everything from a murderous psychopath to a depraved tyrant. Is it time to reexamine this notorious emperor's legacy?

A heartless tyrant and narcissist who ordered the murder of his own relatives to cling to power: This is the profile most usually associated with Nero, the fifth and last emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. It’s not surprising that this image prevails. Classical sources presented Nero as a depraved, oversexed tyrant with an erratic personality, who lived and ruled under the thumb of his ambitious mother, Agrippina the Younger. But curiously, while the ancient authors focused on his ruthless egotism, the political propaganda of Nero’s time also highlighted the emperor’s clemency. Despite the fact that Nero’s government, especially in its final years, systematically persecuted Christians and wiped out dissidents, the Roman Empire under Nero also experienced some of its greatest moments of economic and cultural dynamism.

An unworthy emperor?

When Emperor Claudius died suddenly in A.D. 54, Nero succeeded him to the throne at only 16 years old, leapfrogging over other members of the Julio-Claudian ruling dynasty. Claudius had adopted Nero after marrying Nero’s mother (and Claudius’s own niece), Agrippina the Younger. By naming Nero his heir, Claudius overlooked his biological son Britannicus, but Nero enjoyed popular favor and the support of the Praetorian Guard.

It was Agrippina, Claudius’s fourth wife, who had maneuvered her son into pole position. She had persuaded Claudius to adopt Nero in A.D. 50, and then to allow Nero to marry Claudius’s daughter Octavia in A.D. 53. According to accounts of ancient Roman writers, the following year, once Agrippina was confident Nero’s succession was assured, she had Claudius poisoned.

The ancient authors who depicted Agrippina as a murderess and framed Nero as a cruel tyrant may have had their own agendas. They resented the fact that Nero’s bureaucratization of the imperial administration took power out of the hands of the senatorial class to which those authors belonged. His suppression of indirect taxes in A.D. 58 resulted in greater participation of the common people in trade, which also displeased the aristocracy.

(Roman Empress Agrippina was a master strategist. She paid the price for it.)

Given these grievances, it is likely that ancient authors amplified narratives to discredit him. Among other misdeeds, the sources attribute dozens of homicides to Nero. While he, like many Roman emperors, undoubtedly caused deaths, many of the murders he is accused of seem improbable if the circumstances surrounding them are analyzed.

For example, according to Tacitus, the Roman orator, politician, and historian writing around A.D. 100, Nero murdered his half brother Britannicus out of fear that Agrippina would form an alliance with him. Tacitus adds that Nero and his wife Octavia watched impassively as Britannicus died dramatically in the middle of dinner, while the other diners were in uproar. But when this ill-fated dinner happened in A.D. 55, Agrippina was at the height of her power and had no motive to support a pro-Britannicus change of government. Historian Anthony Barrett of the University of British Columbia argues that, in fact, Britannicus died as a result of an epileptic seizure.

Another gruesome episode attributed to Nero was the death of 400 people enslaved by the senator Lucius Pedanius Secundus. When one of them murdered Secundus, all 400 were sentenced to death. Some Romans rioted, demanding that the innocents be spared. Nero quelled the rebellion and ensured that the mass execution took place. But it was the Senate that had passed this law; Nero simply enforced it. And when some senators suggested that freedmen who had formerly been enslaved by Secundus be exiled from Rome as an additional measure of communal punishment, Nero refused. His position irritated the aristocracy, many of whom he had displaced from key positions in the imperial administration, replacing them with formerly enslaved freedmen in whom he placed his trust.

Life of the party

He prolonged his revels from midday to midnight . . . Sometimes too he closed the inlets and banqueted in public in the great tank, in the Campus Martius, or in the Circus Maximus, waited on by harlots and dancing girls from all over the city.

Nero offered other examples of level-headed rule. Early in his reign, to avoid abuses of power by the sovereign and the Senate, he eliminated secret trials held intra cubiculum principis (literally “inside the prince’s chamber”), which involved the arbitrary condemnation or acquittal of a prisoner. Such private hearings had been common in the time of Claudius, and their suppression was recommended by Nero’s former tutor and mentor, the philosopher Seneca.

Popular with the plebs

By the age of 20, Nero had already forged his own political style and instituted judicial and fiscal reforms benefiting the common people (plebeians). But his political vision was hampered by his mother Agrippina, who, after getting rid of all her rivals, threatened to remove her son from power. The first time that Agrippina was accused of plotting a coup d’état against her son, in A.D. 55, Nero showed clemency. Agrippina had allied herself with Nero’s rival Rubellius Plautus (the great-grandson of Emperor Tiberius). Nero forgave his mother and her accomplice, and he exiled others involved in the plot.

However, when Agrippina again took action against her son three years later, one of Nero’s advisers encouraged him to have her killed while making it look like an accident at sea. According to Tacitus, it was the freedman Anicetus who dreamed up the boat plot, but senator and historian Cassius Dio wrote that Seneca and Nero came up with the idea together. Either way, Nero gave orders to scupper the ship his mother was sailing on off the coast of Naples. Miraculously, Agrippina survived the shipwreck. Then, on March 23, A.D. 59, she was finally assassinated by Nero’s henchmen at her villa in Bauli.

It’s said that a well-known comic actor made a daring allusion in song to the murder. He sang: “Farewell to thee, father; farewell to thee, mother,” while doing a mime of eating and swimming. Claudius had been poisoned while eating dinner, and Agrippina had narrowly escaped being drowned.

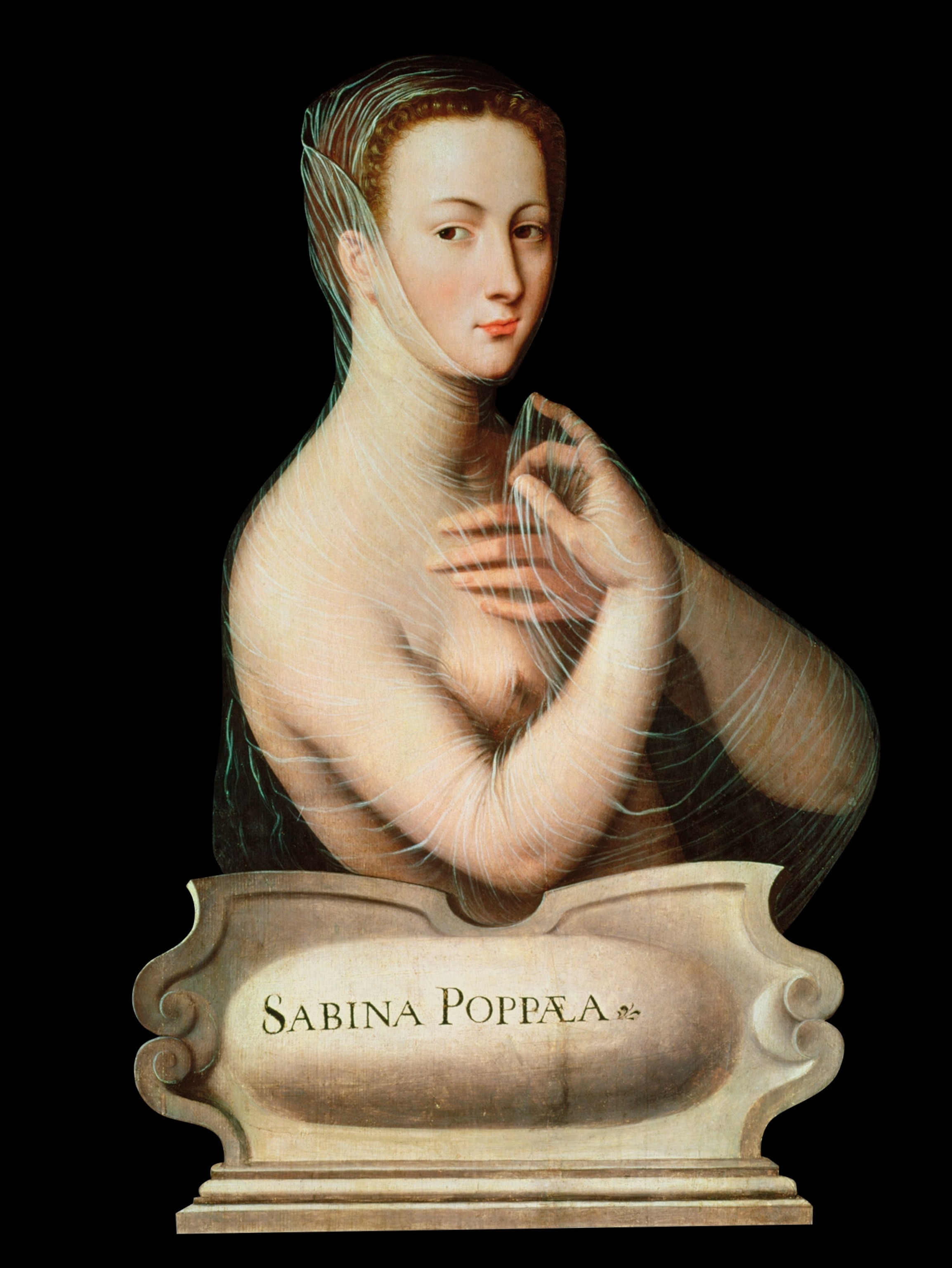

Despite these lurid events, which overshadowed Nero’s reign and detracted from his general policy of clemency, Nero retained considerable popularity by providing the people with bread and circuses. But the support of the common people began to wane when Poppaea Sabina, a beautiful Pompeian woman, appeared on the scene.

In A.D. 62, when Poppaea became pregnant several months into an adulterous relationship with Nero, the emperor decided to divorce his wife Octavia and marry Poppaea. To justify these actions, Nero accused Octavia of adultery with an enslaved person and exiled her to Campania, on the southwest coast. Outraged, the people began to destroy the public images of Poppaea in solidarity with the exiled empress. The revolt forced Nero to bring Octavia back to Rome, but he was now determined to sentence her to death. After facing a second false accusation of adultery, this time with Nero’s former accomplice Anicetus, the commander of the Misenum fleet, Octavia was sent to the island of Pandataria. There, some of the emperor’s assassins murdered her by slashing her veins and immersing her in boiling water.

The animosity the Roman people showed toward Poppaea wasn’t shared in other parts of the empire. In the Campania region, where Poppaea was born in the city of Pompeii, the imperial couple enjoyed popular support. On the walls of Pompeian houses (destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79) archaeologists uncovered graffiti reading “Hail Nero,” “Long Live Poppaea,” and “Hurray for the Emperor and Empress.”

(Pompeii still has many secrets to uncover—but should we keep digging?)

In fact, there was more Pompeian graffiti in favor of Nero than for any previous emperor, and the messages remained visible even after Nero had been sentenced to damnatio memoriae, the removal of all his public and private images and inscriptions after his death. Nero’s special popularity in Pompeii can be explained not only by Poppaea’s Pompeian origin but also by the favors that Nero granted the city. He contributed to Pompeii’s recovery after an earthquake devastated it in A.D. 62, and he visited in person to make offerings at the temple of Venus. Nero also gained popularity by allowing Pompeians to return to their amphitheater early.

Octavia's gruesome murder

No exile ever filled the eyes of beholders with tears of greater compassion . . . After a few days, she received an order that she was to die . . . She was then tightly bound with cords, and the veins of every limb were opened; but as her blood was congealed by terror and flowed too slowly, she was killed outright by the steam of an intensely hot bath. To this was added the yet more appalling horror of Poppaea beholding the severed head which was conveyed to Rome.

The oil painting “Revenge of Poppea” by the 19th‐ century Italian artist Giovanni Muzzioli depicts the moment that Poppaea gloats over the severed head of Octavia, presented to her on a plat‐er. Nero’s new wife reclines on a couch, leaning against the emperor, who appears markedly indifferent to the gruesome sight of his ex‐wife’s disembodied head. By contrast, two senators to his right are visibly shocked. The clothing, furniture, and art that decorate the walls in this painting were carefully designed by the artist to depict Rome in the A.D. 60s It is now displayed in the Civic Museum of Modena, Italy.

Their games had been banned for 10 years, as punishment for a brawl that had broken out in the crowd at a gladiatorial contest when locals clashed violently with spectators from neighboring Nuceria. To cement the loyalty of the Pompeians, Nero reopened it after just five years.

Not unique

The violence of Nero’s reign, as depicted by the ancient biographers, intensified in the A.D. 60s. Ongoing conflict between the Senate and the emperor fueled conspiracies, and Nero ramped up surveillance. Ofonius Tigellinus, prefect of the Praetorian Guard in A.D. 62, led an effective team of spies, who rooted out alleged conspirators. Accused of defaming Nero, the most dangerous rivals of the emperor met untimely deaths: Rubellius Plautus, Faustus Cornelius Sulla, Gaius Calpurnius Piso, Seneca, and many of their co-conspirators.

But Nero’s policy of eliminating adversaries does not differ much from the behavior of the rulers who preceded him. Augustus, who was celebrated as a great emperor, was arguably as aggressive as Nero when it came to dealing with political opponents, ordering all the heirs of his rival Mark Antony killed, for example.

(If not for Nero, Caligula would be rated the Roman Empire's worst emperor.)

Whether an emperor was deemed a champion of the people or a bloodthirsty tyrant depended on the relationship he had with the senatorial class of landowners who wrote the history books. While Augustus safeguarded the privileges of the aristocracy, Nero squeezed them. But the reputations of the two emperors were also shaped by their differing attitudes toward the culture, institutions, and deeply rooted customs of Rome.

(8 things people get wrong about ancient Rome.)

While Rome burns

Nero the innovator

While Augustus maintained a very conservative policy regarding Roman traditions, Nero tried to replace them with new rituals inspired by Hellenistic culture, which he viewed as more civilized. The changes Nero wrought could be considered a cultural revolution. He built gymnasiums, arenas, and imperial schools for teaching the new traditions, where young, aristocratic men were trained to compete in gymnastic and musical contests that were incorporated into Roman festivities.

The aristocracy generally rejected what they saw as cultural Neroism. They criticized his spectacles and poetry recitals, and they ridiculed Nero as a narcissistic megalomaniac who craved public acclaim with his zither playing and singing, increasingly out of touch with the people he ruled.

The end of Nero’s reign was marked by his costly attempt to have a canal at Corinth dug by 6,000 prisoners. By A.D. 66 things were unraveling. Discontent surged among the people, the army, and the senatorial class due to mismanagement of the distribution of wheat and public finances. Nero’s long trip to Greece that year compounded the resentment. Against this backdrop, two provincial governors rebelled against him: Gaius Julius Vindex of Gaul and Servius Sulpicius Galba, Nero’s soon-to-be successor.

(These notorious Roman emperors became ghostly legends.)

In A.D. 68 Nero reluctantly returned to Rome, by now very detached from reality. On June 8, with Galba’s rebellion gaining strength, the Praetorian Guard finally abandoned Nero. The emperor fled Rome with his trusted freedmen Phaon and Epaphroditus and his male lover Sporus.

On June 9 the Senate sentenced Nero to death as a public enemy of the state. Punishment entailed being beaten to death with rods, so Nero decided to commit suicide. Lacking the resolve to take his own life, he asked Epaphroditus to guide his hands by plunging a dagger into his neck.

Nero’s suicide brought the Julio-Claudian dynasty to an end. Given his reputation, one might anticipate that his death would prove to be good for Rome. But the power vacuum he left ushered in the “year of the four emperors,” a bloody civil war that took place as four would-be rulers jostled for power from June 68 to December 69. It was, according to Tacitus, “a period rich in disasters, frightful in its wars, torn by civil strife, and even in peace full of horrors.”