The hidden meaning behind Rome's famous arch monuments

Public ceremonies, lavish processions, and temporary wooden arches were commonplace after victory in Ancient Rome. But during the height of its power, the emperor decided to change that and leave a lasting legacy.

Temples functioned as sites of worship, and the Colosseum served as an amphitheater for games and spectacles. But triumphal arches—such as the Arch of Constantine—were remarkable for being among the few purely symbolic buildings erected by the Romans. With their decorative sculptures, reliefs, and inscriptions, these monuments provide a wealth of historical sources to researchers, and their excellent state of preservation has secured them pride of place in the collective memory of many generations of scholars, travelers, and politicians interested in the ancient Roman Empire.

The triumphal arch originally grew out of the triumphal parade, a ceremony integral to life in the Roman Republic. These lavish processions through Rome were a way for generals and their soldiers to celebrate their military victories publicly. The general who had won a just war was entitled to a pompa triumphalis paid for by the Senate. Members of the Senate, followed by chariots filled with the spoils of war, would lead the processions through the city, finishing at Capitoline Hill. Prisoners trudged in chains before the victorious general, who stood as he rode in a chariot. The triumph culminated with a banquet and games for the whole population, festivities that could last several days.

Celebrating a win

Victory processions entered Rome through a gate in the city wall, the porta triumphalis. On passing into the city, the victorious general officially lost his imperium—the full military executive authority granted to him at the beginning of the war. Crossing this threshold symbolically ended the military conflict.

Over the centuries, the porta triumphalis became a central part of celebrating a victory. Perhaps to recall and reinforce the act of passing through the porta triumphalis, triumphal arches were erected elsewhere in the city. Unfortunately, neither the original porta triumphalis nor the subsequent arches built during the republican period have been preserved, but there is literary evidence of their existence. According to Livy, a Roman historian writing around the time of Jesus’ birth, the Roman general Scipio Africanus, having returned victorious from the Second Punic War in 201 B.C., ordered a triumphal arch built on Capitoline Hill. Eight decades later, military commander Quintus Fabius Maximus erected another arch at the eastern end of the Forum to commemorate his victory over the Celtic Allobroges people of southeastern France.

During the republic, the construction of temporary triumphal arches was part of a strategy that used popular celebration and ceremony to promote prominent generals and politicians in the city. These arches were probably made of wood and likely took the form of a freestanding canopy supported on four pillars (called a baldachin). Although richly decorated, the wooden arches were doomed to destruction at the end of the festivities.

An imperial monument

With the advent of the empire, Augustus retained imperium maius, or “greater power,” and became the leader of all generals, which meant generals could no longer erect triumphal arches. This became a privilege reserved exclusively for the imperial family.

Anatomy of the artworks

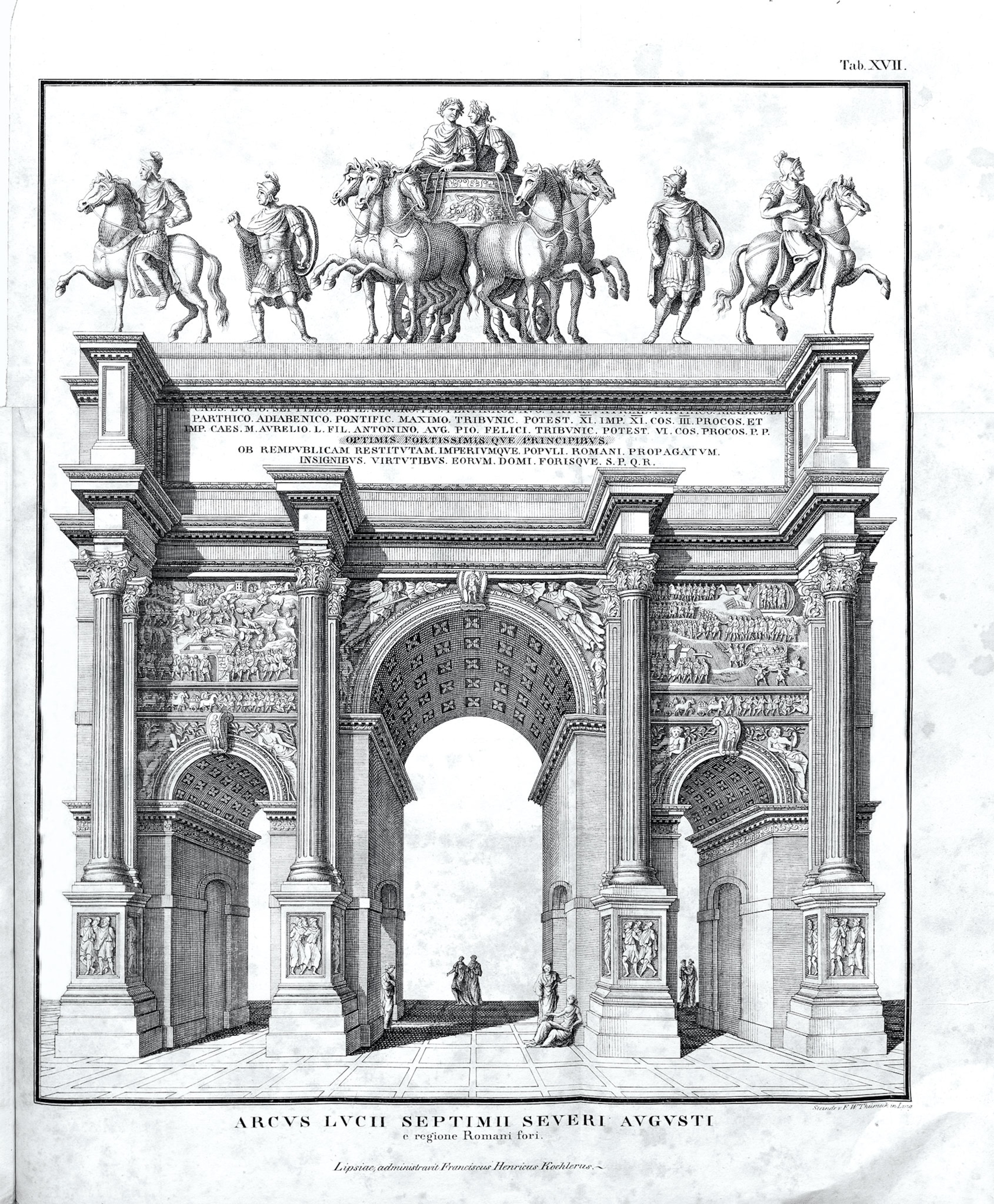

The upper part of the arch is covered in a marble panel bearing a Latin inscription in gold lettering that reads:

TO THE EMPEROR CAESAR LUCIUS SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS SON OF MARCUS, ... FATHER OF HIS COUNTRY, CONQUEROR OF THE PARTHIANS IN ARABIA AND SYRIA, PONTIFF MAXIMUS, IN THE 11TH YEAR OF HIS RULE, CONSUL 3 TIMES, AND PROCONSUL, AND TO THE EMPEROR CAESAR MARCUS AURELIUS ANTONINUS AUGUSTUS PIUS FELIX [CARACALLA], IN THE SIXTH YEAR OF HIS RULE, CONSUL, AND PROCONSUL ... BEST AND BRAVEST OF PRINCES, DISTINGUISHED FOR HAVING RESTORED THE REPUBLIC AND EXPANDED THE POWER OF THE ROMAN PEOPLE, ... FOR THEIR NOTABLE VIRTUES AT HOME AND ABROAD THE SENATE AND THE ROMAN PEOPLE (DEDICATE THIS MONUMENT).

Four main panels decorating the arch depict wars waged by Septimius Severus against the Parthians and the Arabs. The panel below presents the A.D. 195 siege of the Parthian fortress of Nisibis (Nusaybin today), in present-day southeastern Turkey. The original panel is now badly deteriorated.

Given that some colonies were many hundreds of miles away from the capital in Rome, it was a shrewd political move to keep the ambitions of far-flung generals in check by focusing all reference to victories on the emperor himself. Over time, triumphal arches shifted away from being related to the triumphal parades of generals and instead became commemorative monuments glorifying the emperor alone. Having been transformed into a vehicle of imperial propaganda, triumphal arches proliferated not only in Rome but also across the empire.

(8 things people get wrong about ancient Rome.)

While the triumphal arches of the republican era were short-lived wooden structures, the commemorative arches of the empire, made from stone and Roman cement (opus caementicium), were designed to last. The arch itself became deeper, sometimes extending from 15 to nearly 37 feet from front to back. Two smaller side arches flanking the main arch reinforced the structure and increased the surface area available for reliefs and inscriptions. This decoration was concentrated in the attic section at the top of the arch, which often displayed panels with war scenes depicting weapons taken from the defeated as well as a sculpture of the victor driving a chariot.

The architecture of the arches evolved as the imperial era went on. The few arches that remain from the reign of Augustus, the first emperor (27 B.C.–A.D. 14), have an austere design and appear somewhat out of proportion. Later, the influence of Hellenistic, Syrian, and Mesopotamian art would lead to a mingling of forms as architects experimented with decoration from various architectural schools; the Arch of Titus achieves a particularly attractive balance. Erected in A.D. 81. on the Via Sacra, it is the oldest surviving arch in Rome.

To the victor goes the arch

Many arches from the imperial period, like those of the republican period before it, celebrated a specific military victory. The Arch of Titus was commissioned by Emperor Domitian in A.D. 81 to commemorate the capture of Jerusalem by his elder brother Titus 11 years earlier. In A.D. 203–205, the Arch of Septimius Severus was erected in the Roman Forum and richly decorated to honor the victory of Severus and his sons over the Parthians in Arabia and Assyria.

The Arch of Constantine in Rome, which was built across the Via Triumphalis close to the Colosseum in A.D. 312–315, celebrates Constantine’s victory at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in A.D. 312. It stands around 69 feet tall and boasts elaborate decoration, incorporating an attic above the three lower spans, housing eight panels with high reliefs narrating battle scenes. It also has an inscription dedicating the arch to Constantine, who, according to a standard formula, is referred to as “the greatest, pious, and blessed Augustus.”

Constantine didn’t hesitate to use “spolia,” material repurposed from existing monuments, for his arch. Among these pieces are magnificent depictions of Dacian prisoners, which stand almost 10 feet tall. They date to the time of Trajan (A.D. 98–117) and probably once graced Trajan’s forum, but were relocated by the fourth-century builders of Constantine’s arch to adorn the pedestals of its attic. The finished arch is a confection of plinths, moldings, pedestals, spandrels, and friezes that creates an almost baroque decoration.

Civic successes

The commemorative arches of the imperial period not only celebrated military victories; some also honored civic achievements. The Arch of Augustus in Rimini, for example, marks the restoration of the Via Flaminia. The Arch of Trajan at Beneventum celebrates the completion of the Via Traiana, while Trajan’s arch in Ancona recognizes the expansion of the port there. Other arches were erected as tributes to the imperial dynasty in its farther flung outposts. The Arch of Barà in Tarragona, Spain, was built by a citizen called Lucius Licinius Sura to honor Augustus. During the second century A.D., various honorific arches were erected in North Africa, including the Arch of Marcus Aurelius in what is now Tripoli.

What remained of these Roman arches captured the imagination of later rulers from Charles V to Napoleon. Some cities that had no Roman arches built their own in the Roman style. The 1778 Alcalá Gate in Madrid, the 1791 Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, and Napoleon’s Arc de Triomphe in Paris have become iconic elements of their modern cityscapes. It is a victory for the Roman triumphal arch that the monument’s influence survived long after the empire itself.

(The obelisk is an ancient Egyptian architectural feat. So why are so few in Egypt?)