Meet 5 of history's most elite fighting forces

Using hoplons, horses, and muskets, these fierce fighters changed their worlds.

Throughout history, soldiers have been called to fight for their region, for their country, for their king, for their emperor. And throughout history, they emerged well trained and well equipped to meet the specific military challenges and technologies of their time—whether they were foot soldiers fighting for their ancient Greek city-state; mounted archers conquering Asia; or citizen soldiers taking up arms to win independence for the fledgling United States. Here’s a look at five instrumental soldiers of history, and the influence they wielded.

Ancient Greece’s Hoplites

A heavily armed foot soldier in ancient Greece, hoplites filled the ranks of the Greek armies. Named for the round, three-foot-wide, bronze-covered wood shield they carried, the hoplon, these men were drawn from the propertied classes—citizens who could afford the expensive accouterments of battle, which they were required to bring. Athenian hoplites were occasional soldiers, pulled into service when required. Spartan hoplites, on the other hand, were expert warriors who had been rigorously trained from the age of seven.

(This ancient Greek warship ruled the Mediterranean.)

When fully equipped, each soldier carried the hoplon on his left arm. In his right he held a bronze-tipped spear about seven feet long. A short iron sword served as backup. Helmet, breastplate, and greaves (shin guards), all of bronze, completed the armor, which could weigh 60 pounds. Hoplites fought shoulder to shoulder in a phalanx, tightly packed ranks, typically eight rows deep.

They played a significant role in crucial battles including the Battle of Marathon, the Battle of Thermopylae, and the Peloponnesian War, but as warfare evolved and more professional armies emerged, the traditional hoplite tactics gradually became less dominant on the battlefield.

(These ancient Greek weapons were quite literally toxic.)

Roman legionnaires

The Roman legions were the backbone of the Roman military during the height of the Roman Republic and Empire (circa 3rd century B.C. to 5th century A.D.). As part of a professional unit, they were paid regularly, well trained, and well supplied. Heavily armed with seven-foot javelins and heavy swords and protected by helmet, shield, and breastplate, the legionnaires attacked line by line, hurling the javelins and following up with the blades.

(These three kings ruled Rome. Their bloody reigns sparked a revolution.)

Legionnaires were legendary for being ferocious against their enemies, and almost as ferocious against weakness in their own ranks. “Decimation,” for instance, involved executing one out of every 10 members of a misbehaving cohort.

The soldiers were also hardworking and practical. Engineers accompanied the troops, laboring with them to build mile upon mile of roads, forts, and bridges, a legacy that remains today.

(How Roman gladiators got ready to rumble.)

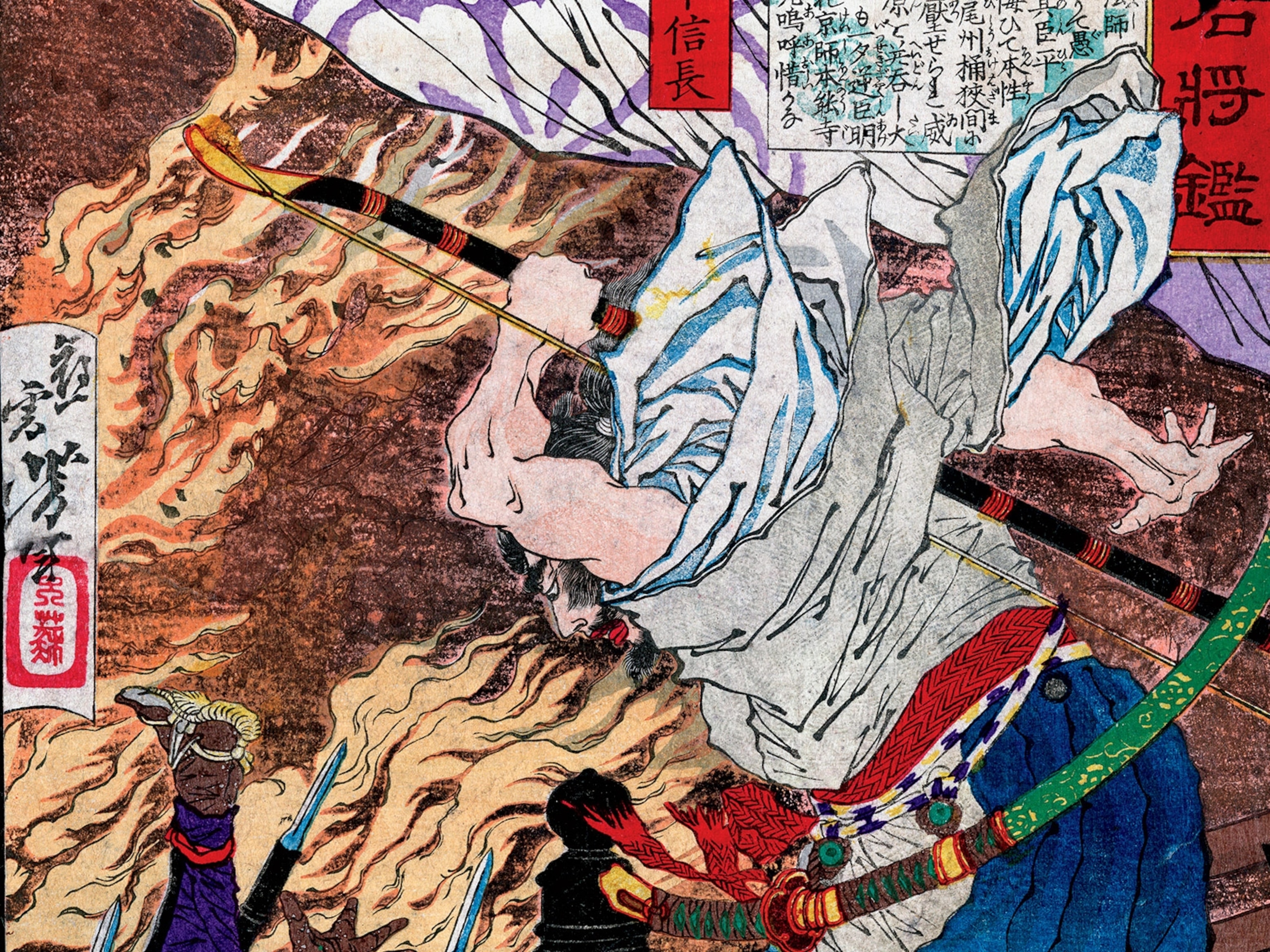

Mongolian mounted archers

Mongolian mounted archers were a formidable and renowned group of warriors who played a crucial role in the military successes of the Mongol Empire, an enormous land empire in the 13th and 14th centuries that originated in modern-day Mongolia and, over time, conquered China, Central Asia, the Middle East, and parts of East Europe. According to Chinese chroniclers, “By nature [the Mongols] are good at riding and archery. Therefore, they took possession of the world through this advantage of bow and horse.”

It’s true that Mongolian fighters—including Genghis Khan and his successors—were bred to the saddle. And their horses, small but strong and fleet, were bred to the steppes. Soldiers typically had several so they could move to a fresh mount when the previous horse tired, keeping up the lightening attacks that led to the conquest of vast territories.

From early childhood, both boys and girls rode and tussled on horseback. As soon as they could reach the stirrups, they learned to wield the Mongolian recurve bow, made from horn, wood, and sinew. Standing in the stirrups, Mongol mounted archers could ride forward and shoot backward; their arrows flew more than 350 yards and at close distance punched through armor. Skilled female mounters defended their tribe when the soldiers were away, and sometimes they joined the front line alongside their male counterparts.

Over time, however, archery become obsolete in a changing world. The once mighty Mongol Empire fragmented into various successor states and eventually faded from its position of dominance.

(Kublai Khan did what Genghis could not—conquer China.)

Spanish conquistadors

The term “conquistador” comes from the Spanish word conquistar, which means “to conquer.” And that they did. Seeking to expand Spanish and Portuguese territory and influence, these seasoned military leaders, explorers, and adventurers—Hernán Cortés, Francisco Pizarro, and Juan Ponce de León among them—led their soldiers to dominate the New World in the 16th century, seeking riches and spreading Christianity—and decimating the indigenous cultures with guns and disease.

(Guns, germs, and horses brought Cortés victory over the mighty Aztec empire.)

Conquistadors were equipped with a mix of traditional European weaponry and armor. Cannons and portable guns were essential. Soldiers also carried a harquebus (sometimes spelled arquebus), a long-barreled matchlock weapon that was slow and awkward in modern standards, invented in the 1400s. As the decades went by, however, other kinds of matchlock and then flintlock guns would replace this weapon of the conquistadors. Their armor included breastplates, helmets, and shield, although not all of them could afford such protection.

As the great empires they served declined, the era of the conquistadors came to an end.

(How Spain’s lust for gold doomed the Inca Empire.)

American militiamen

Lacking a standing army, the American colonies organized their own part-time local regiments for defense. Every able man between 16 and 60 was required to volunteer for occasional training days equipped with his own musket, bullets, and powder. The soldiers who confronted the British at Lexington and Concord on the morning of April 19, 1775, setting the American Revolution in motion, were a specially trained, paid militia that had drilled consistently in the months after the Boston Tea Party.

(What was the ‘Shot Heard Round the World’?)

But most militiamen lacked that level of skill or commitment, and generally they were undisciplined, unruly, and unenthusiastic. George Washington wrote in 1776 that the militia regarded their officers as “no more than a broomstick.” He went on, “If I were called upon to declare … whether the militia had been most serviceable or hurtful upon the whole I should subscribe to the latter.” Nevertheless, these civilian soldiers became effective recruiters for the Continental Army and useful auxiliaries on the Revolutionary War battlefield.

(He was the last king of America. Here’s how he lost the colonies.)

To learn more, check out Atlas of War. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.