What was the ‘Shot Heard Round the World’?

Fired on April 19, 1775, at the Battles of the Lexington and Concord, the blast marked the beginning of the American Revolution.

Late one April night in 1775, Paul Revere made what would become his famous midnight ride to warn of an impending British attack against the people of Massachusetts. For years, tensions had been building across the North American British colonies and were rising ever higher in New England. On April 19, 1775, they would explode at the Battles of Lexington and Concord, which kicked off the American War for Independence.

(George Washington was the calm, cool, collected leader the colonies needed.)

Early rumblings

As 1760 dawned in America, most white colonists were proud Britons, relatively content in the arms of empire. They had grown up with an implicit understanding that risk-taking was their heritage. Their grandparents, parents, or even themselves had left behind the known world to settle in a land filled with opportunity an ocean away. So, when the crown and Parliament suddenly began to assert control over daily life and impinge on that prospect, a smoldering distrust was bred between the British and the American colonists. Within a dozen short years, that distrust turned to outrage and rebellion.

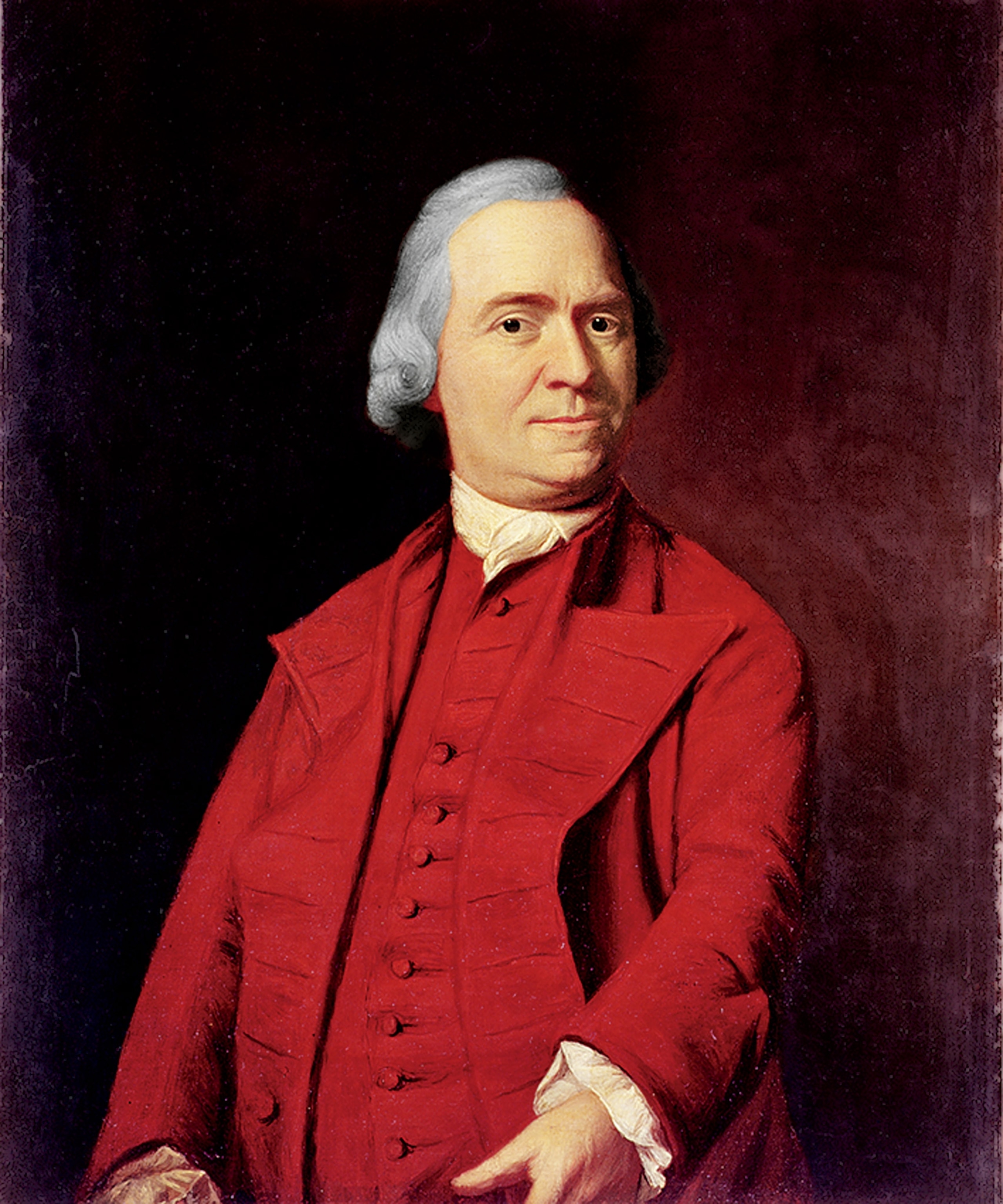

In 1775 Boston, clandestine associations including the Sons of Liberty kept a close eye on both the Loyalists and the British soldiers (known as redcoats), who had been stationed to maintain control among colonists. In London the king, George III, and his Tory compatriots were ready to teach the disgruntled colonists a lesson. “Suppose the colonies do abound in men, what does that signify?” Lord Sandwich asked the House of Lords. Then he answered his own question: “They are raw, undisciplined, cowardly men.”

But the great parliamentarian and political thinker Edmund Burke extolled the colonists’ fierce spirit of liberty: “In this character of the Americans, a love of freedom is the predominating feature which marks and distinguishes the whole . . . your colonies become suspicious, restive, and untractable, whenever they see the least attempt to wrest from them by force … what they think the only advantage worth living for.”

(Rum was the spirit that helped fuel the American Revolution.)

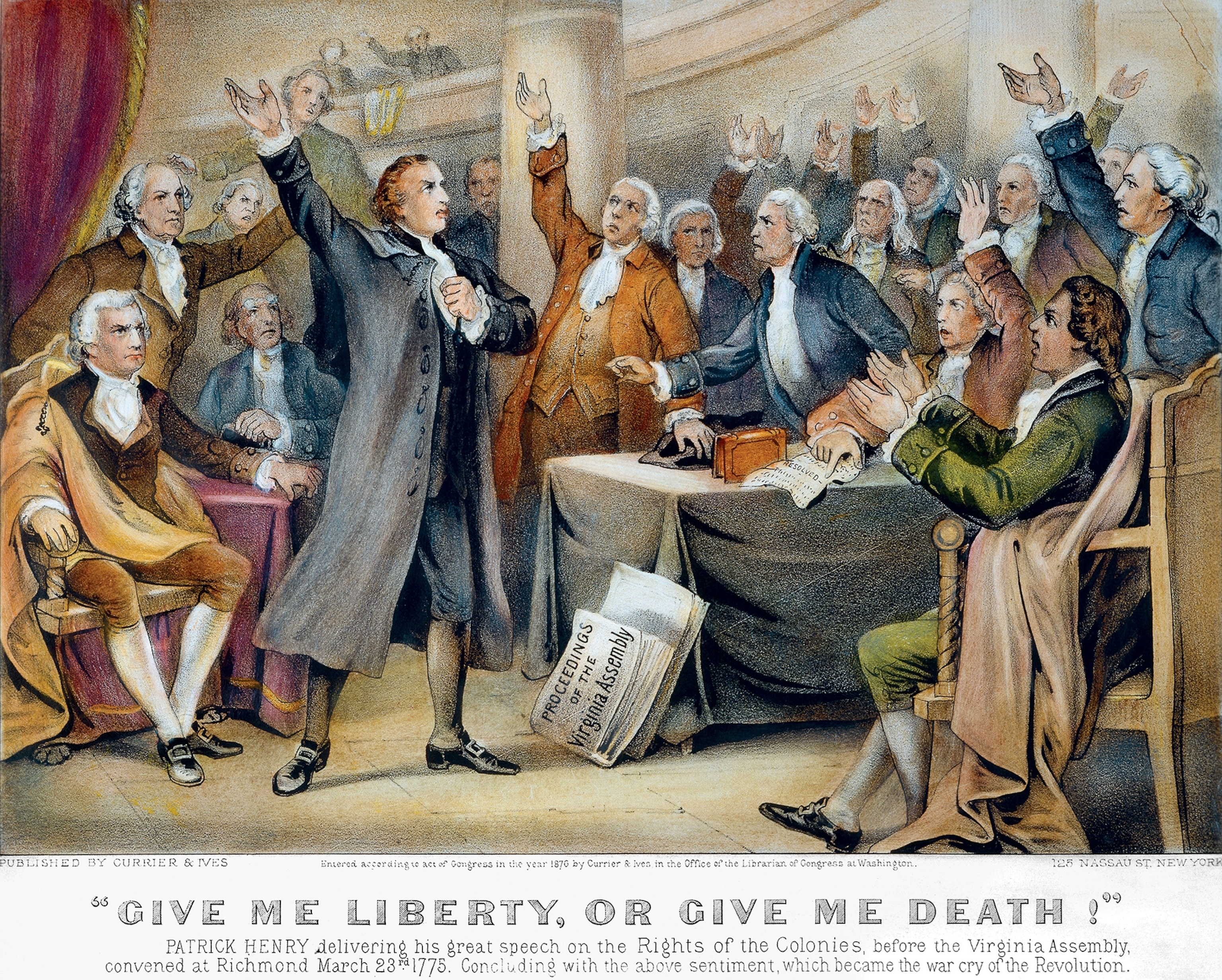

Liberty or death

Meantime, Patrick Henry, a patriot firebrand and member of Virginia’s House of Burgesses, became the full-throated voice of rebellion. “Gentlemen may cry, Peace, Peace—but there is no peace,” Henry thundered to the roughly 120 delegates who gathered in March 1775 in Richmond, at the Second Virginia Convention. “The war is actually begun!” he raged. “The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? . . . I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

This belief in liberty and the human right to it (though not for women, enslaved people and Native Americans) was unprecedented, a new way of conceiving the human condition. For more than a century, it had been growing and maturing in the American ethos, and now the idea of individual freedom was held dear—dear enough to fight for.

In Boston the British commander Thomas Gage understood this. He knew the town he oversaw, probably along with other colonies, was preparing for a fight. Writing for reinforcements, Gage urged his superiors not to underestimate the Americans: “If you think ten thousand men sufficient, send twenty; if one million is thought enough, give two.” His warnings were met with only disdain from his British superiors, though some reinforcements were sent his way.

The Americans had no seasoned generals of their own and no military beyond their militias and more elite minutemen, trained to assemble on the double-quick. They also had no serious supplies of weaponry or munitions, except what was officially stored in magazines and armories scattered in towns throughout the colonies.

(How a smallpox epidemic nearly derailed the U.S. War for Independence.)

The conflict deepens

Earlier, in December 1774, the redcoats and the colonists skirmished over a substantial supply of gunpowder, cannons, and small arms stored in a New Hampshire coastal fort. “Things now every day begin to grow more and more serious,” Lord Percy wrote home in early April 1775. Percy, one of the commanders posted to Boston to serve with General Gage, had watched as conditions in the port city worsened: little food, bad water, and no inclination on the townsfolk’s part to assist the redcoats occupying their home turf and patrolling their streets.

Desertion rose in the British ranks, and Gage was encouraged from London to take some kind of decisive action against the Americans. In mid-April, the orders that reached him were more explicit: “Arrest and imprison the principal actors and abettors of the Provincial Congress whose proceedings appear in every light to be acts of treason and rebellion.”

Boston’s Sons of Liberty got wind of these orders, thanks to their allies in London, and they waited and watched.

A cautious man, Gage sent out spies to reconnoiter the surrounding countryside so he could plan a good target for his first action. Soon, he had it: the town of Concord, less than 20 miles northwest of Boston. His spies, and Loyalists within the town itself, had assured him it was a storehouse of colonial arms.

Paul Revere’s ride

At the ready, Paul Revere, ardent colonist and Boston Tea Party activist, and his compatriots came up with a plan to signal any troop movement: “If the British went out by Water, we would shew two Lanthorns in the North Church Steeple. If by land, one.” Around ten o’clock on the evening of April 18, two dim lights appeared in the steeple. Revere then quietly crossed the Charles River to Charlestown, where “a very good horse” was waiting.

Outrunning a British patrol, Revere rode for Lexington, rousing militiamen along the way. Local men left their warm beds and prepared to muster as citizen soldiers. About midnight, Revere reached Lexington and warned John Hancock and Samuel Adams (both had taken refuge there) that the British were coming.

(Americans have been taking down statues going all the way back to the Revolution.)

The first shot

Through the cold spring night, some 800 or 900 redcoats marched west from Charlestown. In the dawn half-light, they rounded a bend and saw about 70 militiamen clustered in a corner of the Lexington common. A British commander shouted to the Americans, “Lay down your arms, you damned rebels!” Some dispersed, but none laid down their arms. A shot rang out, precipitating a “continual roar of musketry” from the British, then a bayonet charge. Eight Americans lay dead and ten wounded. Eventually, the British regulars formed up and continued the march to Concord.

At Concord, the British found little in the way of munitions, but to their astonishment, they skirmished again with local militiamen outside the town. When the patriots opened fire, the redcoats broke and ran back to Concord. As the exhausted redcoats set out on the return march to Boston, they were harassed by American fire. Only the appearance of a thousand redcoat reinforcements saved the original column.

Word of Lexington and Concord spread quickly. The Revolutionary War had begun.

Lasting legacy

More than 50 years later, a battle monument was dedicated in Concord to honor the patriots who had fought in April 1775. It was there on July 4, 1837, Ralph Waldo Emerson debuted his famous "Concord Hymn," perhaps better known today by the phrase he coined to describe the battles themselves: He called them "the shot heard round the world." Since 1894, Massachusetts has commemorated the start of the Revolutionary War with Patriots’ Day, typically held the third Monday in April, with reenactments at Lexington and Concord, the Boston Marathon, and parades.

To learn more, check out Founding Fathers. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.