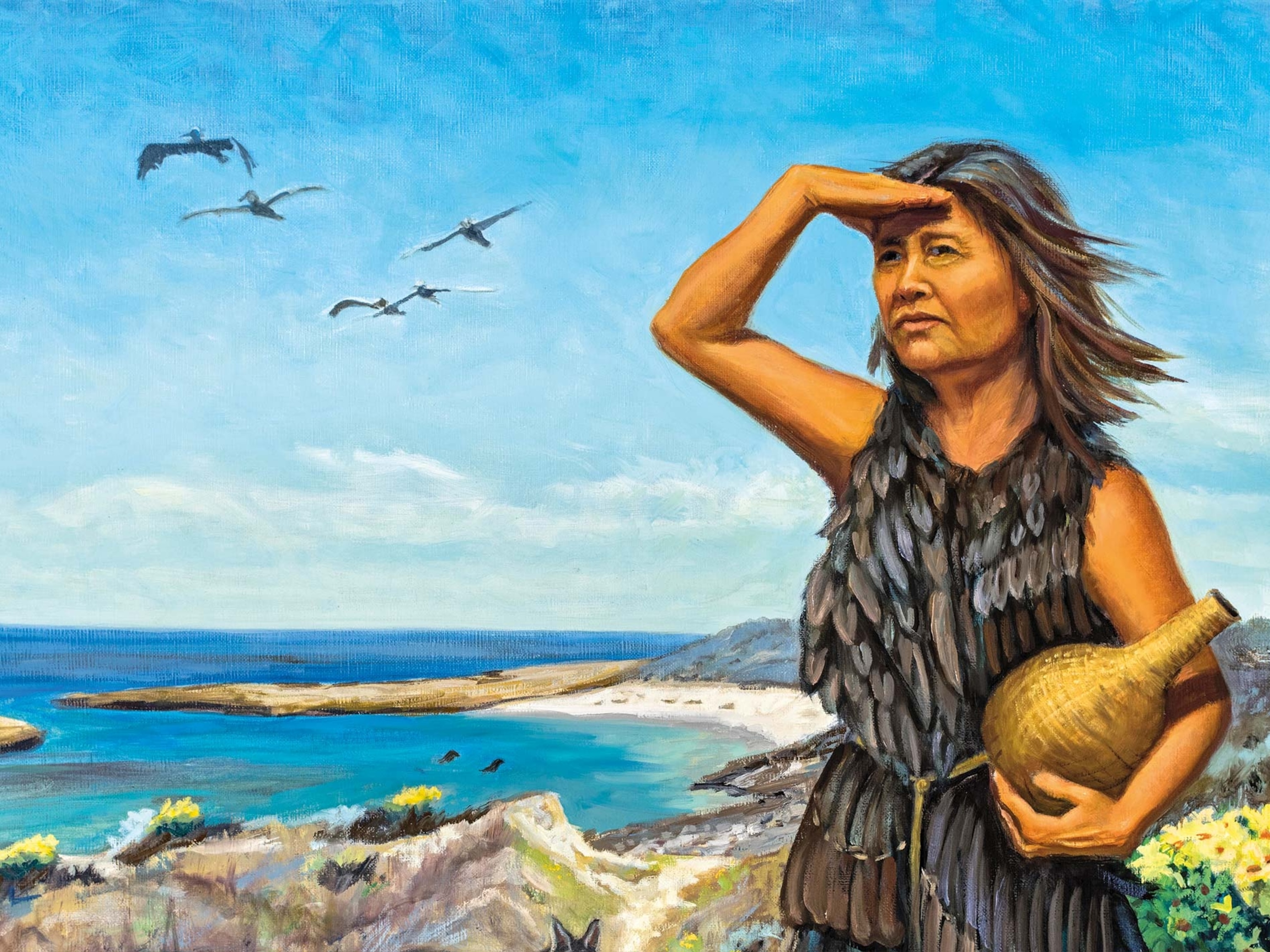

Who were the women conquistadors in the Americas?

From financing expeditions in the New World to founding hospitals and schools, these women were incredibly influential—and granted more power than their counterparts back home.

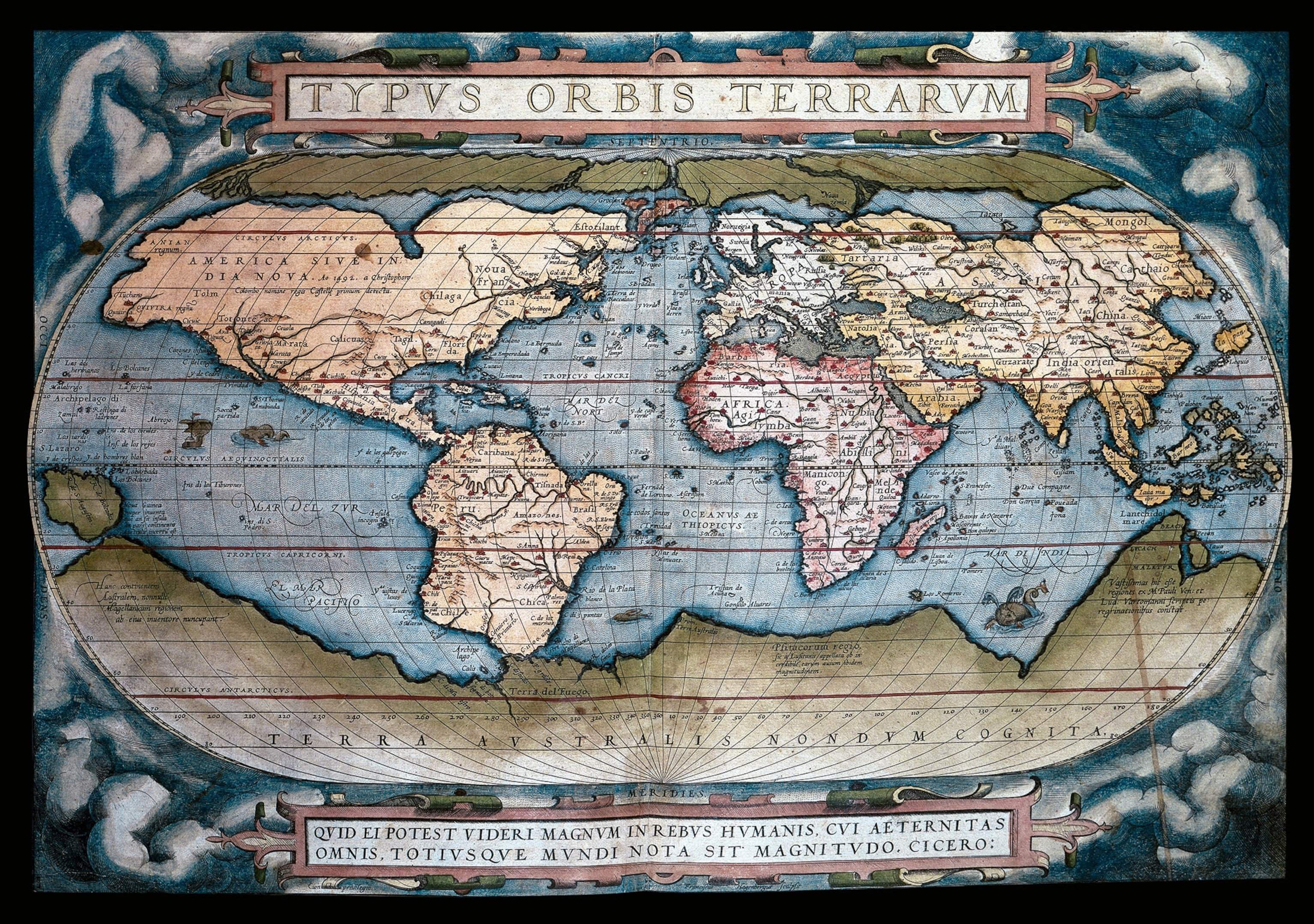

Spanish women played a critical yet lesser known role in the colonization of the Americas by mastering their ability to assert power in the New World. It all began with Queen Isabella I of Castile, the first queen of Spain, who financed Christopher Columbus’s expedition in 1492 that ultimately led to the discovery of the Americas.

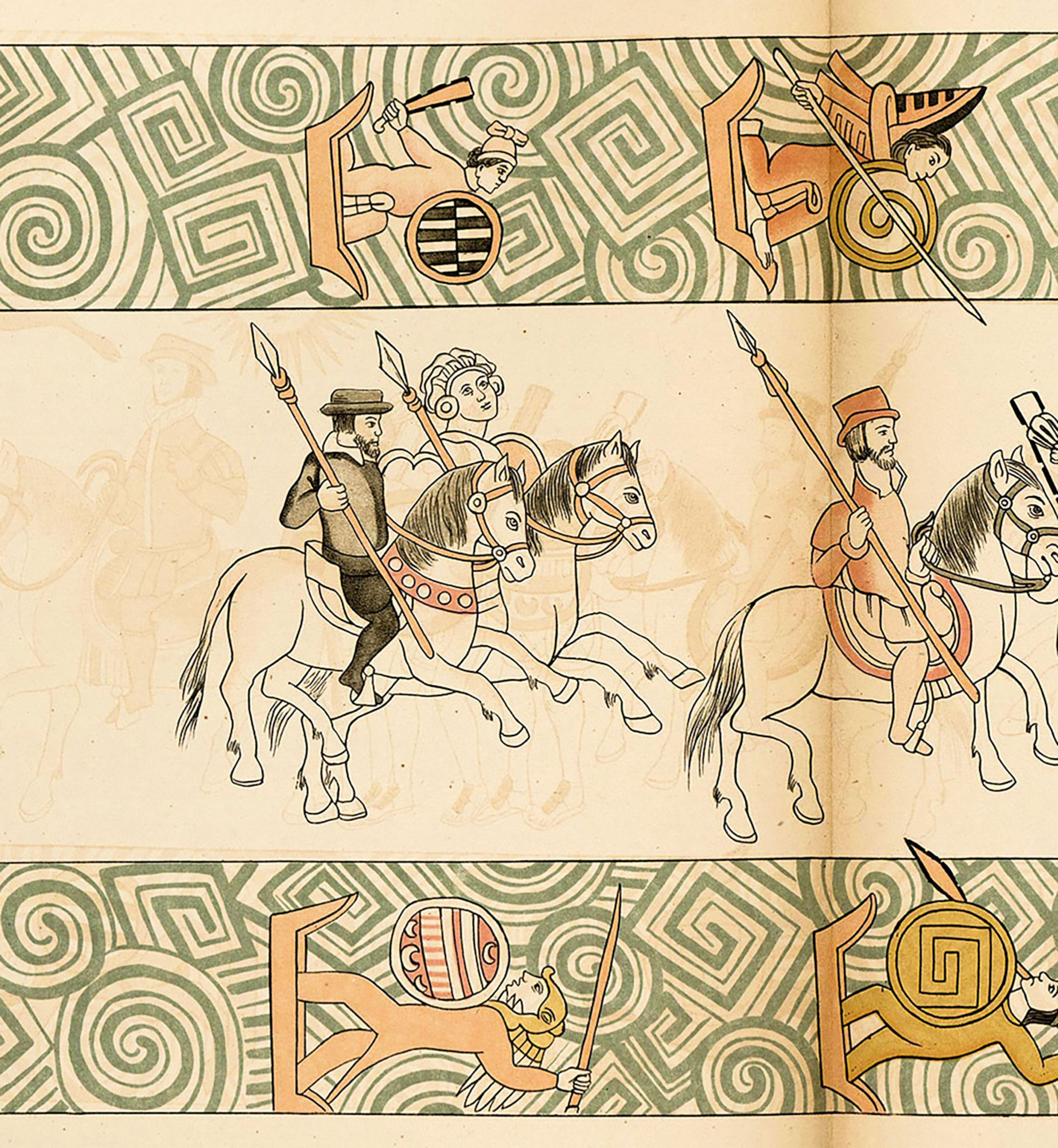

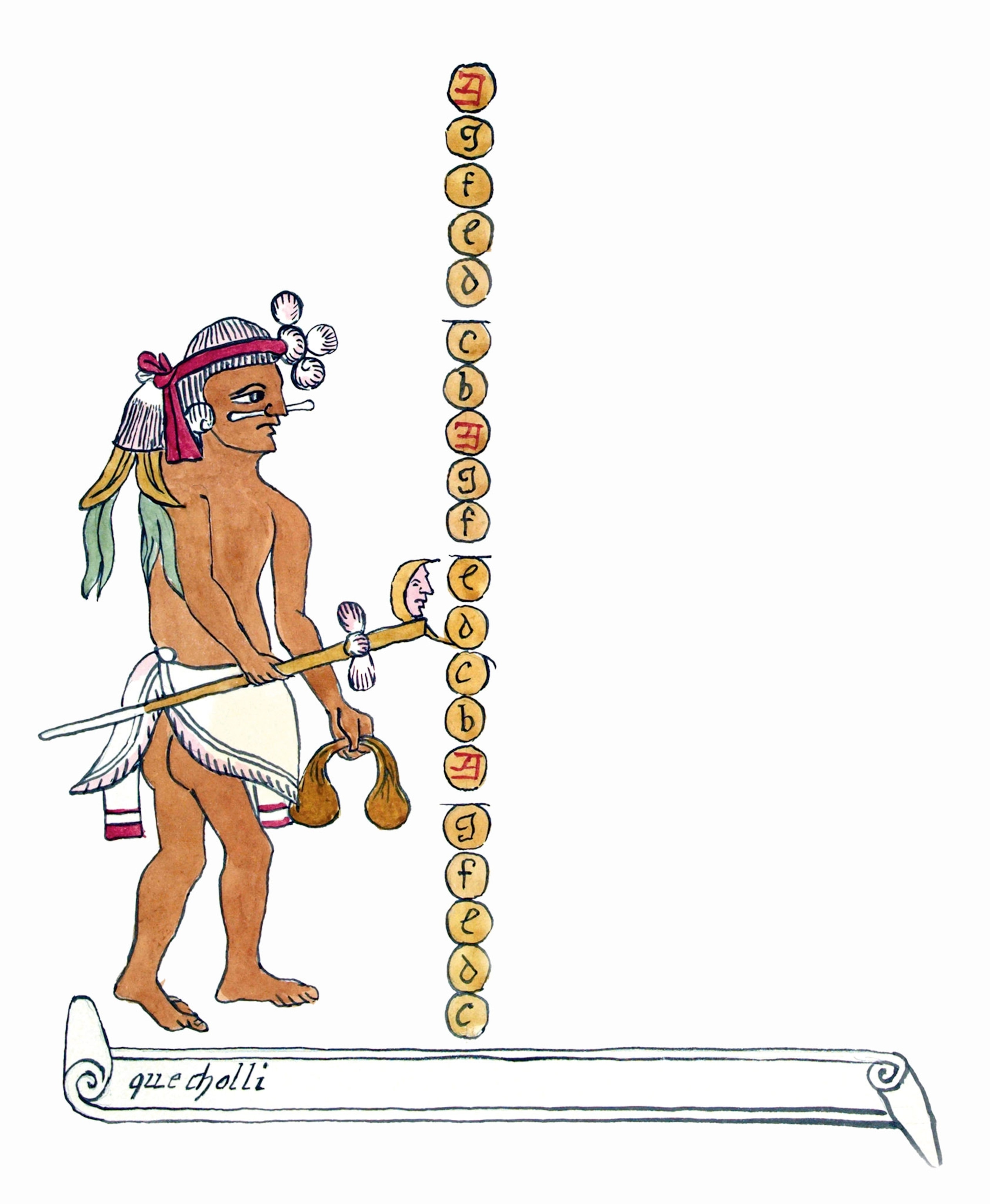

A stream of Spanish women, eventually numbering in the thousands, left their homes in Europe and embarked on transatlantic voyages to the New World. These women experienced hardships at sea and perils on arrival, just like their male counterparts, and yet their names were often overlooked by royal officials and chroniclers. They joined with male expeditionaries in clearing jungles, crossing mountain ranges and deserts, and navigating mighty rivers. Women helped build cities, engaged in political affairs, and founded hospitals and schools. Some also fought against the Indigenous peoples. They were mothers to both the criollos (people of European descent, born in the Spanish colonies) and, along with many Indigenous women, mothers to the mestizos (mixed-race people of Spanish and Indigenous descent).

Discoverers

While the names of the men who set sail from Spain throughout the 16th and 17th centuries are relatively easy to track down, the women who went with them left less of a paper trail. According to records from the House of Commerce in Seville, which handled all the administration surrounding expeditions to the Americas, there were four female travelers among the 1,500 people on Columbus’s second expedition in September 1493: María Fernández, “maidservant to the Admiral [Columbus];” María de Granada, about whom no more details are given, and the merchants Catalina Rodríguez, “a native of Sanlúcar,” and Catalina Vázquez.

On Columbus’s third voyage, which set sail from Sanlucár de Barrameda in southern Spain in May 1498, 30 women were listed. Some were wives of the male expeditionaries, such as Catalina de Sevilla, who appeared registered with her husband, Pedro de Salamanca. But the officials at the House of Commerce also granted boarding permits to atypical characters, such as a prostitute, Gracia de Segovia, and two Romany travelers, Catalina and María of Egypt. It is surprising that Romany women were among the first from Spain to the Americas, given that Romanies were persecuted in 16th-century Spain. Catalina and María were convicted criminals. In exchange for commuted sentences, they signed up to be laundresses on board and to complete 10 years of unpaid service in the Americas. This was an exception to Spanish regulations, since the crown had a special interest in the “newly discovered” territories being populated by “good people.” They wanted Spanish traditions to govern life in the Americas. The authorities were also keen for single women to join the expeditions in the hopes that they would end up marrying the single Spanish men who were setting out to make a life in the New World.

(Watch archaeologists reveal the Vasco da Gama shipwreck.)

One example of this was the expedition organized to bring single Spanish women and Spanish families to the recently founded city of Asunción, in Paraguay. The influx of single men from Spain had led to a situation where a Jesuit of the time said, “One Spanish man lives with up to ten Guaraní women.” In April 1550 an expedition including 60 women left Sanlúcar de Barrameda. It was commanded by Mencía Calderón de Sanabria, a noblewoman from Badajoz, in southwest Spain. Her late husband, Juan Sanabria, had been appointed adelantado (governor) of Río de la Plata and had signed an agreement with the Spanish crown to organize and lead the expedition to Asunción. But he died before being able to carry it out, and the title of adelantado passed to his teenage son from a previous marriage. The plan had been for the expedition to “carry in six ships, 80 married men with their wives and children, 20 marriageable maidens, and a further 250 single people, men and women of any age.” Although the Sanabria Calderón family borrowed money against the farm they owned, they couldn’t get enough money to meet all these contractual demands. But despite the setbacks, three ships with 300 people on board set sail with the mission of bringing some order to the city of Asunción.

Wives of the American colonists

The trip was full of incident and chaos. A storm scattered the three ships, and then in the Gulf of Guinea, a corsair boarded the light patache the women were traveling on and assaulted many of them. They suffered famine on the island of Santa Catarina, off the coast of Brazil, and imprisonment in the Portuguese fort of Santos, near present-day São Paulo. They fought the Tamoyo cannibals and faced five years of illness and desperation, losing many of their party, before reaching their destination. The 22 men and 21 women who finally arrived in Asunción in May 1556 had been traveling for six years and one month, and in that time they had covered more than 10,500 miles over sea and land.

(He was shipwrecked in Texas in 1528. His unlikely tale of survival became legend.)

Explorers

A significant number of women took part in the Spanish voyages of discovery, even though the chronicles tend to overlook their role. It is not widely known that when Francisco de Orellana sailed up the Amazon he was accompanied by his wife, Ana de Ayala, and a large group of women born in Trujillo, western Spain. Orellana’s expedition numbered about 400 people when they set out from Sanlúcar on May 11, 1545. But the voyage turned to disaster as supplies ran short; many people deserted the ships in the Canary Islands and Cape Verde, and some ships were wrecked. In December the survivors arrived at Marajó Island on the Brazilian coast in the Amazon Delta, ready to “enter the mouth of the Amazon and explore the river as far as the border region with Peru.”

For 11 months the expedition members navigated some 550 miles along tributaries and dead-end channels in an agonizing odyssey of disease, hunger, and armed conflict with the local people. Many died from these incidents. When they returned to the mouth of the river and entered a village in search of food, Orellana was shot and killed by a local, the arrow that killed him piercing his heart. In November 1546, Ana de Ayala and 43 men, the sole survivors of the expedition, built a boat and headed to Margarita Island in present-day Venezuela. Although she outlived her husband, Ana de Ayala received little mention in records of the expedition.

Colonizers

The women who came to America as settlers suffered the same hardships as their male companions and often fought alongside them against the Indigenous people they encountered. In 1536 an expedition under the command of Pedro de Mendoza arrived at the Río de la Plata estuary on the southeast coast of South America and established the fort of Espíritu Santo. This nucleus would develop into the city of Buenos Aires. Some of those on Mendoza’s expedition were traveling as family units, but there were also widows and single women cohabiting with male expeditionaries. María Dávila, “companion” to Mendoza, was one of these, as was Elvira Pineda, “loving servant” to Captain Osorio. Other women, such as Isabel de Guevara, stood out for their courage and forbearance when some 23,000 Querandí people besieged the fort of Espíritu Santo and the port of Buenos Aires in June 1536.

The Granadan Puma whisperer

Many of those under siege died of dysentery and lack of food and drinking water. In the middle of the Southern Hemisphere winter, as the situation became desperate, the Spaniards began to eat their horses. When there was not a rat, snake, or blade of grass left to eat, they gnawed on leather belts and shoes. Franciscan poet Luis de Miranda writes in graphic detail about the horrors of the famine in his elegiac poem about the founding of Buenos Aires: “The dung and feces that which some could not digest, many other sad people did eat” and “They also ate human flesh ... The very offal of a brother!”

Some survivors were finally able to flee the siege by ship and make their way upriver. With many of the men sick or injured, the women joined in steering the ship and fighting off attacks from local people. They chose a place to settle and there founded the city of Nuestra Señora Santa María de la Asunción, now known simply as Asunción, which became the capital of Paraguay. This is how Isabel de Guevara describes the early days in Asunción in a letter she sent from the city to Princess Governor Juana of Austria in 1556, 20 years later. The women had to work, “making clearings with their own hands, scratching and scraping and sowing and collecting the supplies, without help from anyone.” She goes on to complain that she had not received from the governor of Asunción the parcels she considered her due as one of the first Spanish women to arrive at the Río de la Plata.

War was part of life for the Spanish men and women who sought to colonize the New World. Some women took up arms, like María de Estrada during the conquest of Mexico. Together with Hernán Cortés and Pedro de Alvarado, she entered Tenochtitlán in 1519. After the Battle of Otumba, the Franciscan chronicler Fray Juan de Torquemada wrote that Estrada, armed “with sword and shield did marvelous deeds and went against the enemy with such courage and spirit as if she were one of the bravest men in the world.” She then played a role in provisioning of the Spanish army before the final attack on the capital of the Mexica empire.

(Guns, germs, and horses brought Cortés victory over the mighty Aztec empire.)

Warriors

In 1541 the Mixtón War broke out in the kingdom of Nueva Galicia (western Mexico). When the local Chichimec people besieged the capital city of Guadalajara, one of its inhabitants, Beatriz Hernández, acted with determination. As chronicled by the Jesuit historian Mariano Cuevas, she addressed all the terrified women who were crying in the church, saying, “now is not the time for fainting,” before taking them to the safe house and locking them in. Hernández then put on light body armor and took up a short lance. Throughout the battle, she protected the entrance to the building and the women and children sheltering inside. The founding charter of Guadalajara contains the names of the 63 colonizers who survived the battle against the Chichimec; among them is Beatriz Hernández.

Another brave woman, Doña Mencía de los Nidos, stood firm in the defense of the city of Concepción, in southern Chile. And when, in 1554, Governor Francisco de Villagrá ordered the evacuation of the main square because of the threat of the Araucanians, she refused to withdraw. Soldier and poet Alonso de Ercilla recalls what happened in La Araucana:

She heard a great uproar, and was galvanised Grabbing a sword and a shield, she went after her neighbors as best she could... “Come back! ... I offer myself here, to be the first to throw myself in the enemy irons!”

Despite their courage, the surviving Spaniards had to take refuge in Santiago de Chile.

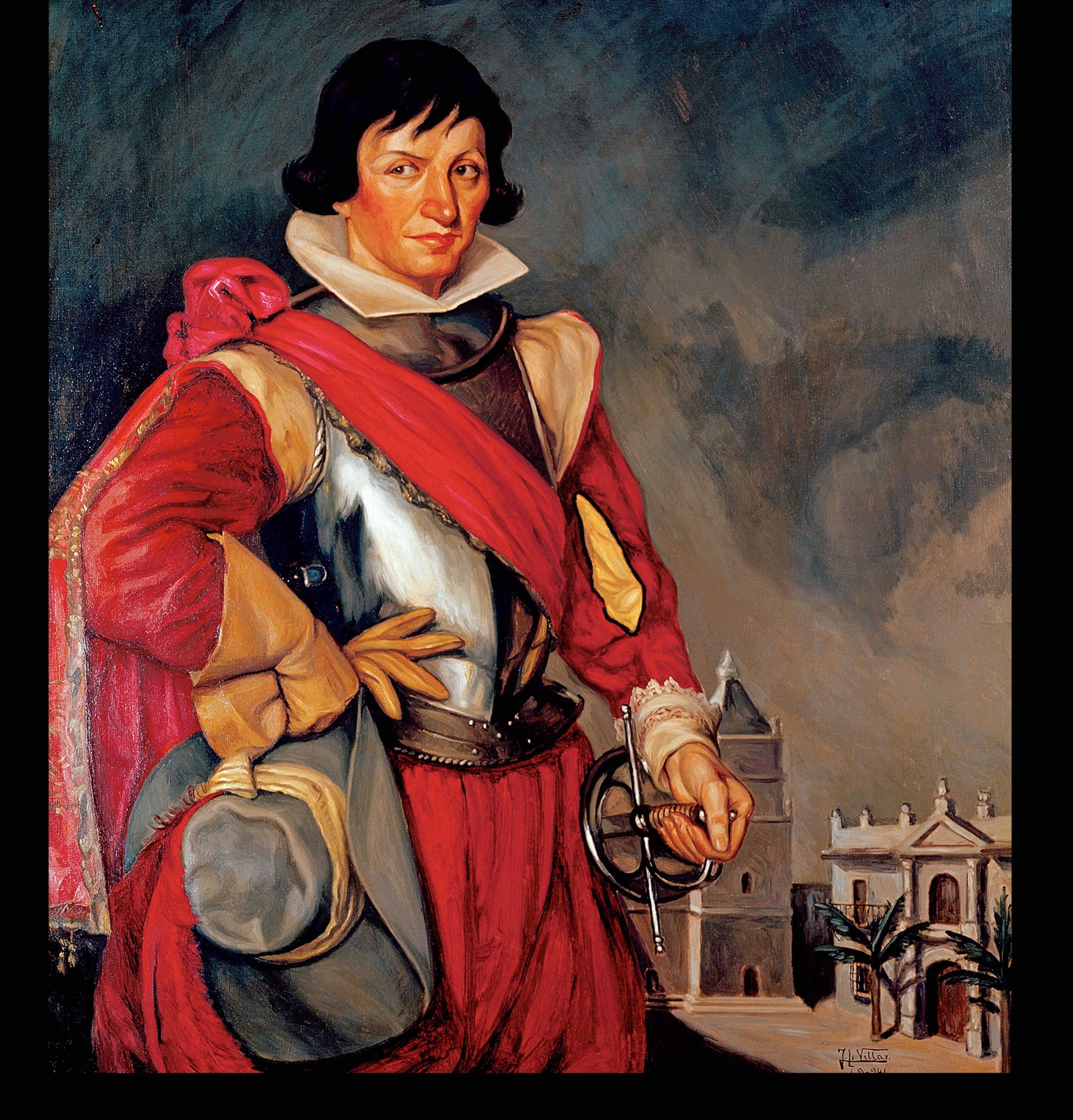

But the best known female soldier of the Spanish conquest of America is, without a doubt, Catalina de Erauso, also known as the Monja Alférez (Lieutenant Nun). As a teenager she escaped from a convent in San Sebastián, passed herself off as a boy, and served as a page for various illustrious figures. In 1603, at age 18, she boarded a ship in Sanlúcar and set sail for the New World. Once in Lima, she changed her name to Alonso Díaz. In 1606 she enlisted to fight the Araucanians (today’s Mapuche), who were closing in on the city of Concepción and the Valdivia fort in Chile.

In one of the many battles during the war, the Araucanians killed the captain and lieutenant of Erauso’s company. Erauso and two soldiers jumped onto their horses and chased the group of Indigenous people who had seized the Spanish flag. With her two companions injured, Erauso continued the pursuit. She writes in her autobiography, “I, with a bad blow to the leg, killed the chieftain who was carrying it [the flag] and took it from him, and I pressed on with my horse, running over, killing and wounding countless; but badly wounded and run through with three arrows and a spear in the left shoulder ... I fell from my horse.” She stayed in that place with some companions for nine months, after which she finally returned to the Spanish camp with the flag. It was then that Erauso obtained the rank of second lieutenant. She wasn’t granted the highest rank because she’d had the chieftain hanged instead of handing him over for questioning, as the governor had ordered.

In her autobiography, Erauso tells how sometime later, after a brawl, she ended up recounting her life story to the bishop of Guamanga, near Cusco. “The truth is this,” she says. Having left the convent and changed her appearance to that of a man, “I embarked, contributed, brought stuff, killed, wounded, harassed, ran around, until coming to stop in the present at your most illustrious feet.” After two and a half years in a convent in Lima with the purpose of purging her crimes, the authorities allowed Erauso to return to Spain, since she clearly lacked interest in the religious life. Dressed as a man, she arrived in Cádiz on November 1, 1624, and was welcomed by cheering crowds. The king allowed Erauso to use the name Antonio instead of Catalina and provided an encomienda (a parcel of land manned by local laborers, who were not enslaved but often worked under abusive conditions) in Veracruz, Mexico. Antonio de Erauso died at the age of 65 in Cuitlaxtla, near the encomienda.

The power of command was not forbidden to the Spanish women who arrived in America. In the absence of their husbands, or after their husbands’ deaths, many women succeeded their spouses in certain positions. Such was the case of Isabel Barreto, known as the adelantada (female governor) of the South Seas.

(Meet 5 of history's most elite fighting forces: including the conquistadors.)

Governors

With her dowry, which amounted to 40,000 ducats, Barreto helped her husband, the captain and governor Álvaro de Mendaña, fund and charter four ships, which left Piura, Peru, in June 1595. The expedition, made up of 280 men and 98 women and children, set sail for the Solomon Islands, in the middle of the South Pacific.

The lure of the Pacific

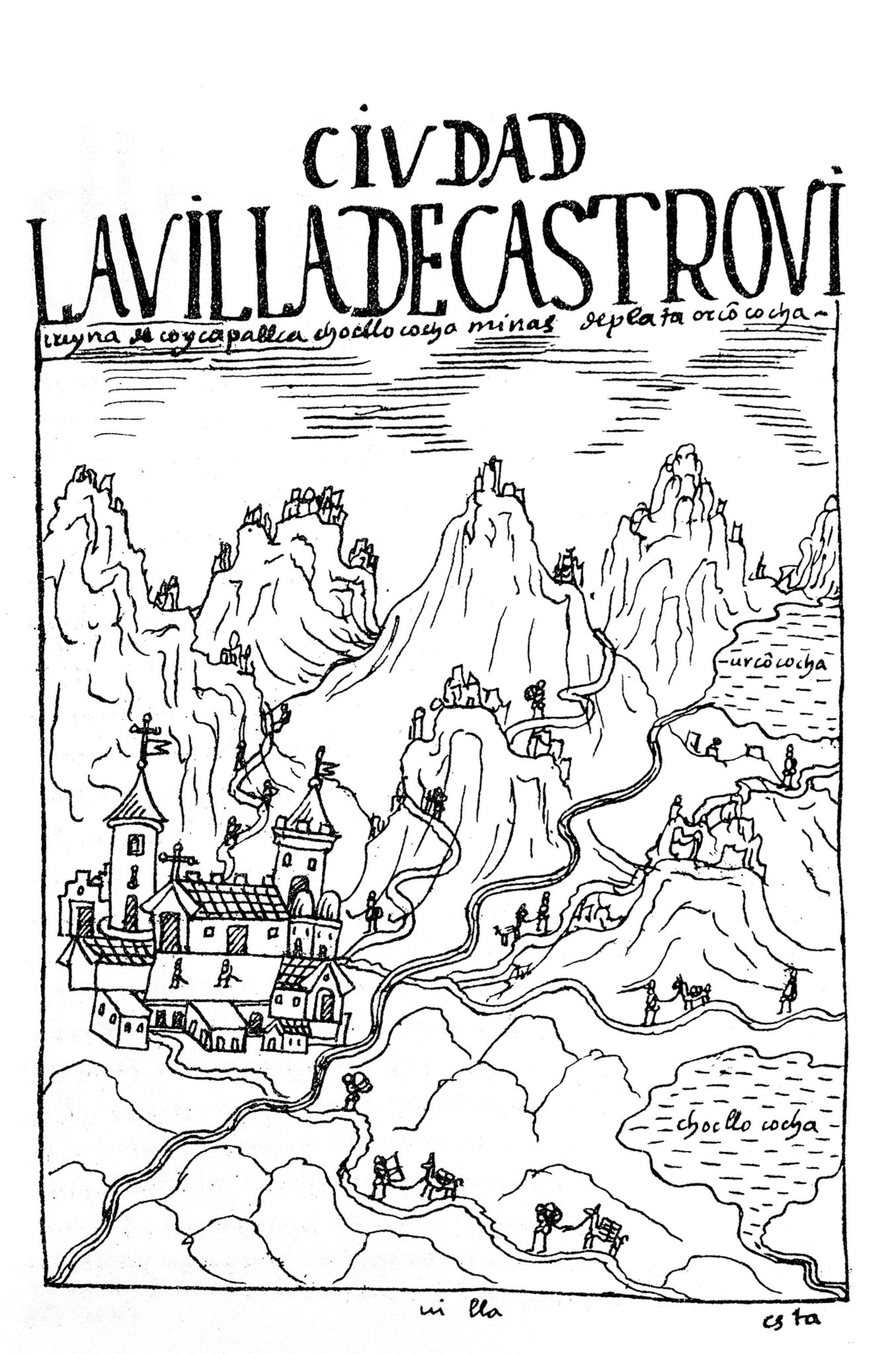

During the expedition, Mendaña became seriously ill. According to the chronicle of ship pilot Fernández de Quirós, Medaña, in his will, named Barreto his “universal heir, governor of the discovered lands and those yet to be discovered.” When Mendaña died, Barreto took on leadership of the expedition, ordering that they explore the nearby archipelagoes in search of gold and pearls. The four ships sailed for several months until they reached the Philippines, where Barreto was received as the “Queen Sheba of the Solomon Islands.”

Barreto settled in the Philippines, marrying the nephew of the governor of Manila. In August 1597, the couple left for Acapulco. After a short stay in Mexico, they settled in Castrovirreyna, Peru, where Barreto died in September 1612.

(How Spain’s lust for gold doomed the Inca Empire.)

Professional women

The legislation that regulated the emigration of Spanish women was strict, aimed at protecting their reputation and safeguarding family unity. Permission to travel was not usually granted to single women unless they embarked as servants or were going to meet with family. But immigration to the New World was a different matter, as it was generally thought that having more Spanish women would have a positive impact on the new colonies and increase the population.

Whether rich or poor, from the nobility or from peasant stock, the Spanish women who traveled to America tended to enjoy more autonomy and freedom than the women who stayed in Europe. Many carved out professional lives as businesswomen, nurses, midwives, teachers, and writers. Some took on traditionally male roles as expedition captains, soldiers, colonial commissioners, governors, and even viceroys, thus shaping their own futures and the New World.

The first criollas of Spanish America