The first sack of Rome wasn't when you think it was

The Gauls—not the infamous Vandals or Visigoths—were the first to conquer Rome and plunder the city for its wealth. Their leader's words would haunt Romans for generations: “Vae victis—Woe to the vanquished.”

The Roman Republic was booming in the beginning of the fourth century B.C. Wealthy and powerful, it had just defeated the Etruscan city of Veii, amassed an immense war chest, and doubled its territory. But then, out of the blue, the republic suffered the unthinkable: occupation by a Celtic people, the Gauls. This was the first time that Rome and Gaul would face off, but it would not be the last.

Over the coming centuries, the Romans and the Gauls would clash many times. But this first defeat in 387 B.C. caused a collective trauma for Rome that lasted generations, shaping Roman attitudes toward all peoples from the north.

(How was Rome founded? Not in a day, and not by twins.)

Early encounters

By 600 B.C. the Gallic people Insubres had already settled south of the Alps, where they founded Mediolanum (today’s Milan). Over the next two centuries, other Gallic peoples would do the same and expand into southern and western Europe. Around 400 B.C. the Senones settled on the shores of the Adriatic, in the region that the Romans would later call Ager Gallicus. But this settlement was still a safe distance from Rome and on the other side of the Apennines that form the mountainous backbone of the Italian peninsula.

A decade later, the Senones crossed the mountains and attacked the Etruscan city of Clusium, about 90 miles north of Rome. Writing more than four centuries later, the Roman historian Livy described this Gallic expansion and how the people of Clusium appealed to Rome for help (they were denied). Roman historians described the Gauls in big sweeping strokes, which were likely exaggerated. The Gauls were tall, pale, long-haired, blond, and mustached. Some of them, according to first-century B.C. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, lightened their hair with “lime-water.”

There are various theories as to why they made this incursion into the Italian peninsula. In general, Roman sources suggest that the Gauls were less developed as a society than the inhabitants of Italy and coveted their farmland, in particular their wine. In the first century A.D., centuries after early Gallic expansion, the Greek scholar Plutarch wrote that when the Gauls tasted wine for the first time they became “beside themselves with the novel pleasure which it gave” and they set off “inquest of the land which produced such fruit, considering the rest of the world barren and wild.” Although the Gauls’ fondness for wine did tend to be exaggerated, there was a kernel of truth to it. Later, Italian and Roman wine merchants would enter Gaul as the peaceful forerunners to the legions that would follow.

(One of Italy’s most visited places is an under-appreciated wine capital.)

Seasoned warriors

The Gauls were visually striking because of their clothing, which was dyed with bright colors. Unlike the Romans, the men wore pants (bracae in Latin), a garment typical of the nomadic horsemen of the Eurasian steppes. The Greeks and Romans considered it barbaric—even effeminate—for men to wear such attire. The elite among the Gauls wore jewelry, most notably torques, which are thick metal necklaces of gold or silver, open at the front and twisted like braids. In 361 B.C., some years after the assault on Rome, a young Roman called Titus Manlius came face-to-face with a gigantic Gallic warrior in single combat. Despite the Gaul’s immense size—in Roman tales the height of the Celts is always emphasized—Titus defeated him, seized his torque, and was known thereafter as Torquatus, a moniker that would pass to his descendants.

As for protection in conflict, many Gallic warriors had nothing more than an elongated oval shield and a helmet adorned with feathers. Their typical weapon was a long sword, best suited for slashing. Many stereotypes grew up about the ferocity with which the Gauls fought; allegedly it was more daunting than that of other adversaries the Romans had faced until then. Writing in the first centuries B.C. and A.D., Greek historian Strabo explained:

The whole race which is now called both “Gallic” and “Galatic” is war-mad, and both high-spirited and quick for battle, although otherwise simple and not ill-mannered. And therefore, if roused, they come together all at once for the struggle ... As for their might, it arises partly from their large physique and partly from their numbers.

According to classical sources, the Gauls attacked en masse to the sound of their war horns, without the use of tactical formations or reserve troops. Strabo felt it would make it easier over time for the Romans to conquer Gaul than Hispania, home of the Iberians. Whereas the Gauls tended to “fall upon their opponents all at once and in great numbers,” meaning they would be “defeated all at once,” the Iberians “would husband their resources and divide their struggles, carrying on war in the manner of brigands, different men at different times and in separate divisions.”

Battle of the Allia

The Etruscans of Clusium called on Rome to help them. The Senate sent three ambassadors who entreated Brennus, leader of the Gallic Senones, to withdraw. When Brennus refused, the ambassadors, instead of returning to Rome, joined the ranks of Clusium in trying to repel the Gauls. By throwing their support so obviously behind the Clusines, they contravened the law of nations, the equivalent of current international law. This decision gave Brennus a pretext to declare war on Rome. After defeating the Clusines, Brennus led his troops south toward Rome. Livy described their terrifying procession: “The whole country in front and around was now swarming with the enemy, who, being as a nation given to wild outbreaks, had by their hideous howls and discordant clamor filled everything with dreadful noise.”

(These three Etruscan kings ruled Rome. Their bloody reigns sparked a revolution.)

A Roman army marched north and intercepted the Gauls less than 10 miles outside the city on the banks of the Allia River, a tributary of the Tiber. It was the first time that the legions had fought against the Gauls, and the result was disastrous. The Romans were outnumbered, a situation that happened often in their clashes with the Gauls.

As a result, the tribunes of consular rank who commanded the Roman army redeployed soldiers to the flanks. The center, with ranks depleted, was soon breached, and the Gauls surged unstoppably forward. The legionaries from the left flank fled to the neighboring city of Veii, 10 miles northwest of Rome, while those on the right retreated to the capital itself.

Three days later, Brennus and his army of Gauls stood at the gates of Rome. The city was exposed, for it lacked a complete perimeter wall. The bulk of the population fled—even the Vestal Virgins, guardians of the city’s sacred fire. With no one to oppose them, the Gauls stormed into Rome and pillaged the city. High-ranking elderly senators, who had refused to be evacuated, sat in their curule chairs in the middle of the Forum or, according to some sources, in the atria of their houses.

(The Vandals sacked Rome, but do they deserve their reputation?)

Roman sources claim that when the first Gauls arrived, they were stunned by the dignity and composure of these elder statesmen. One invader allegedly tugged at the long white beard of Senator Marcus Papirius to see if the figure might be a statue. Papirius responded with a blow from his cane. The Gaul then killed Papirius with his sword, and his companions massacred the rest. Brennus’s men looted and destroyed the city as the terrified populace looked on. Livy wrote:

In whatever direction, their attention was drawn by the shouts of the enemy, the shrieks of the women and boys, the roar of the flames, and the crash of houses falling in, thither they turned their eyes and minds as though set by Fortune to be spectators of their country’s fall, powerless to protect anything left of all they possessed beyond their lives.

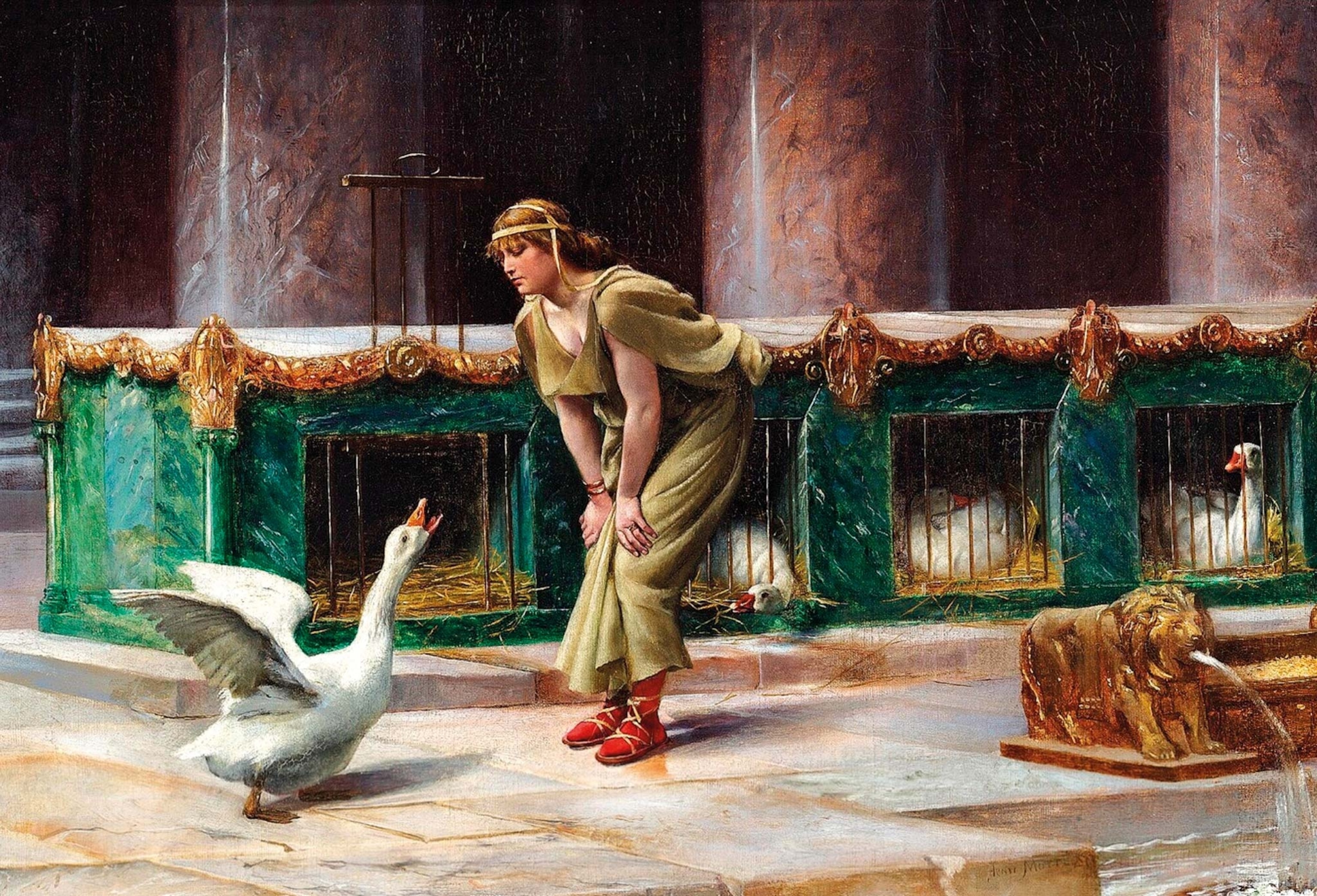

Some Romans had managed to take refuge on the Capitoline Hill and were safely hidden. But the Gauls spotted footprints going up the hill that belonged to a messenger, who the Romans had sent to Ardea to seek help. The Gauls followed the same route and sent an advance party up the hillside that very night. Neither the Roman guards nor their watchdogs heard them coming, but geese sacred to the goddess Juno that lived there did. The alarmed honking alerted the Roman defenders, who took up arms and forced their attackers back.

Sounds (and honks) of alarm

Woe to the vanquished

Seven months passed and the Gauls held their siege. But it took its toll on them. According to Livy, “They had their camp on low-lying ground between the hills, which had been scorched by the fires and was full of malaria ... Accustomed as a nation to wet and cold, they could not stand this at all, and tortured as they were by heat and suffocation, disease became rife among them, and they died off like sheep.”

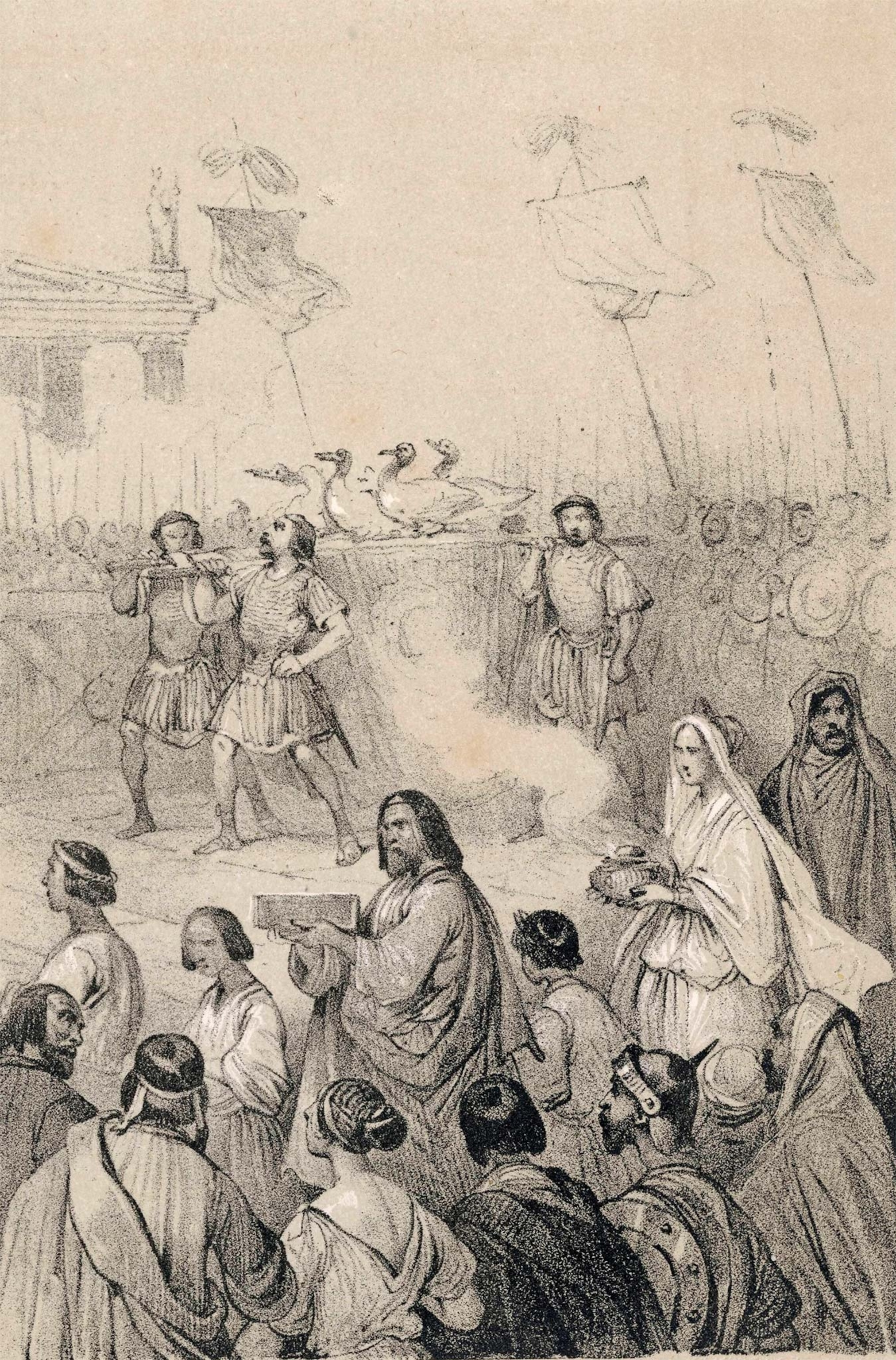

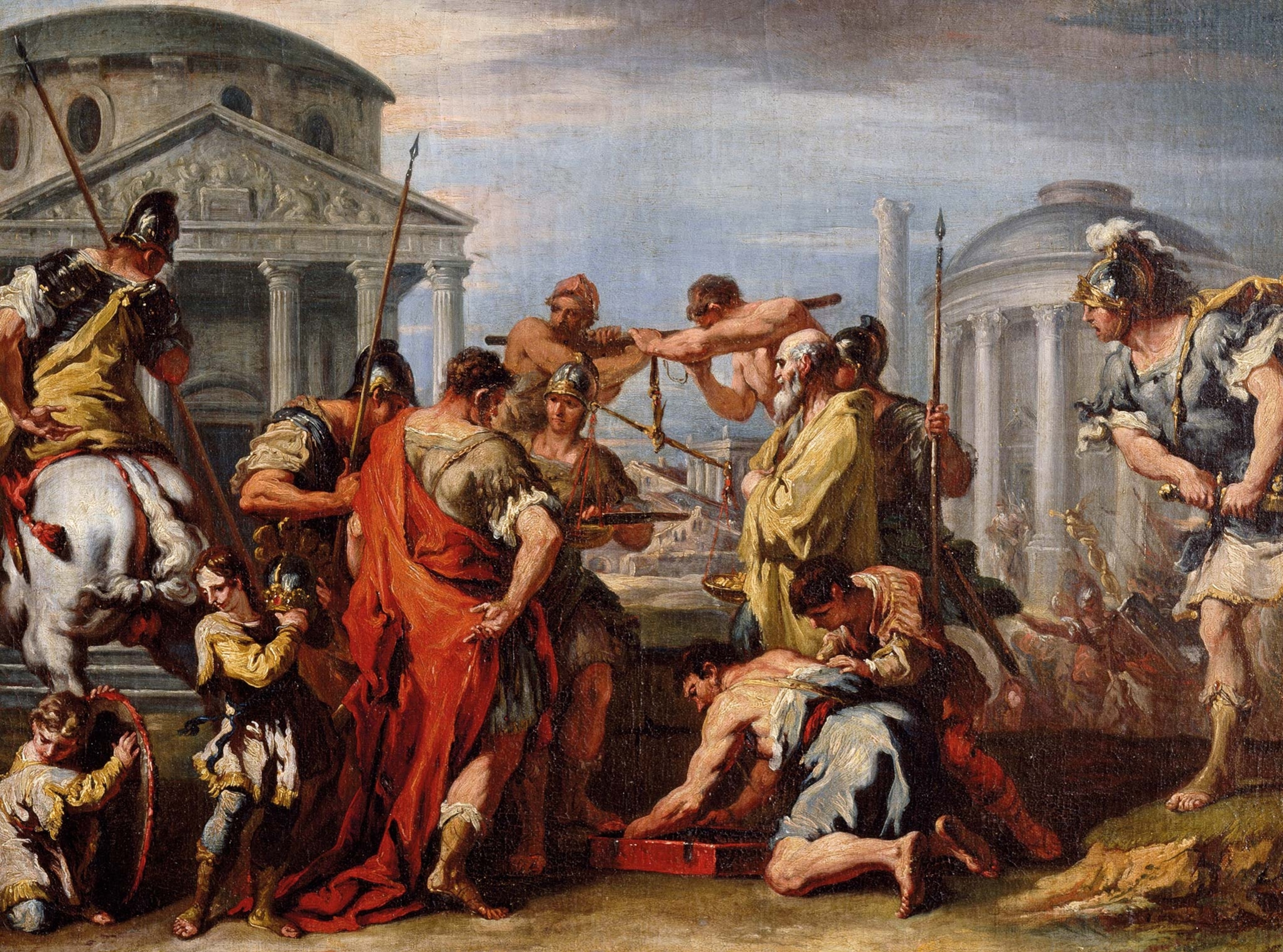

At last, a negotiated settlement was reached. The Gauls agreed to leave Rome in exchange for a thousand pounds of gold. The defenders came down from Capitoline Hill bearing treasures and weighed them in the Forum before their conquerors. When the tribune Quintus Sulpicius noticed the Gauls were putting fake weights onto the scales in order to claim more riches, he complained. Brennus dropped his own sword onto the scales and exclaimed, “Vae victis—Woe to the vanquished.” Resigned, the Romans handed over even more gold to offset the weight of the sword.

Roman historians differ on how the Gallic siege ended. Both Plutarch and Livy say that Marcus Furius Camillus, an exiled general, responds to Rome’s call for help. He is appointed dictator and uses his might to expel the Gallic forces. Writing in the second century B.C., the historian Polybius makes no mention of Camillus or an expulsion of the Gauls. Rather, in his telling, Rome pays a ransom and the Gauls simply leave.

Facts and fictions

Classical sources undoubtedly contain factual details, but legendary elements and exaggerations are woven among them. There is some evidence to show that Rome did suffer a defeat and sacking around 387 B.C.: Greek authors such as Aristotle and Heraclides of Pontus, who were writing not long after the events, mention an invasion. Archaeologists, however, have not found evidence of mass destruction and fires as terrible as in Livy’s writings. Rome appears to have recovered very quickly in the years that followed, which would have been unlikely if the damage were as severe as described. Evidence suggests that rather than a Gallic army set on occupation, the invaders were a band of warriors who attacked Rome in a quick raid. They probably looted what they could but did not demolish buildings or set fire to the city.

The story of the Gallic invasion as retold in the histories written centuries later is evidence of metus gallicus, an exaggerated fear of Gauls and other northern peoples. This prejudice was galvanized at the end of the second century B.C. as groups of Germanic Cimbri and Teutoni people pushed south into Roman territory. Metus gallicus would become a driving force in Rome’s expansionary policy. The perceived threat would serve as the pretext for Julius Caesar’s first-century B.C. campaigns in Gaul, and it also explains why his victories over the Gauls were celebrated with an unprecedented 15 or even 20 days of thanksgiving back home in Rome.

(How Julius Caesar started a big war by crossing from Gaul to Italy.)

Keeping their heads