This is what a surgical clinic looked like in ancient Rome

Discovered on accident in Rimini, Italy, this surgeon’s house and the hooks, scalpels, and mortars inside have expanded what we knew about ancient medicine.

Workers were hardly surprised when they stumbled upon ancient ruins in the Italian town of Rimini in 1989. Now a popular tourist destination along the Adriatic coast, Rimini—or Ariminum in ancient times—had been a major Roman town for centuries, and the modern city is strewn with monuments from that period.

What the workers found that spring day, however, would lead archaeologists to something quite unique: a cache of surgical instruments that had lain undisturbed in a Roman surgeon’s clinic for centuries, offering tantalizing new details about the practice of medicine in the classical world.

(Honey enemas and healing dreams: Inside the world of ancient medical tourism.)

An everyday marvel

Workers were busy landscaping the public gardens of the Piazza Ferrari, the city’s central square, when they noticed fragments of stucco caught up in the roots of a tree. The City Museum of Rimini confirmed the fragments were Roman, and a team of archaeologists moved in to carry out probes on-site.

These revealed the remains of a cluster of well-to-do, but otherwise ordinary, houses, a discovery that promised to shed new light on everyday life in Ariminum.

Once part of the Etruscan civilization of northern Italy, Ariminum was conquered by the Roman Republic and given its Latin name in 268 B.C. Already an important port, it later stood at the junction of the Via Aemilia (the highway linking the eastern coast to the northern part of the Italian peninsula) and the Via Flaminia (the road to Rome).

This vital harbor and transport hub acquired impressive and long-lasting infrastructure that is still visible today: sections of the old city wall; the triumphal Arch of Augustus, erected in 27 B.C., marking the starting point of the Via Flaminia; and the marble splendor of the Tiberius Bridge, completed around A.D. 21.

From these, historians had a good idea of Ariminum’s place in the Roman world, but they knew less about what day-to-day life was like there. The 1989 discovery would change that.

The archaeologists expanded the area of investigation and began a series of annual excavation campaigns that lasted until 1997. In total, they excavated a site of about 7,500 square feet, uncovering remains from a range of periods, spanning from the imperial Roman era to the later Byzantine period.

The site included part of the first-century city wall and three houses. The oldest of these houses was Roman, occupied until the third century; the second and third houses were Byzantine.

Doctor in the house

What caught the attention of archaeologists most was the first of these houses, which had been rebuilt several times over the years. The last reconstruction took place during the second half of the second century A,D., when the main rooms were remodeled to include rich mosaics and paintings and new rooms were added. Archaeologists were able to identify the areas of a typical Roman mansion: the vestibule; the triclinium (where banquets, receptions, and social gatherings were held); several cubicula (rooms usually identified as bedrooms that also served as reading or meeting rooms); and a latrine. They also found remains of a richly decorated upper floor comprising several rooms, including a kitchen.

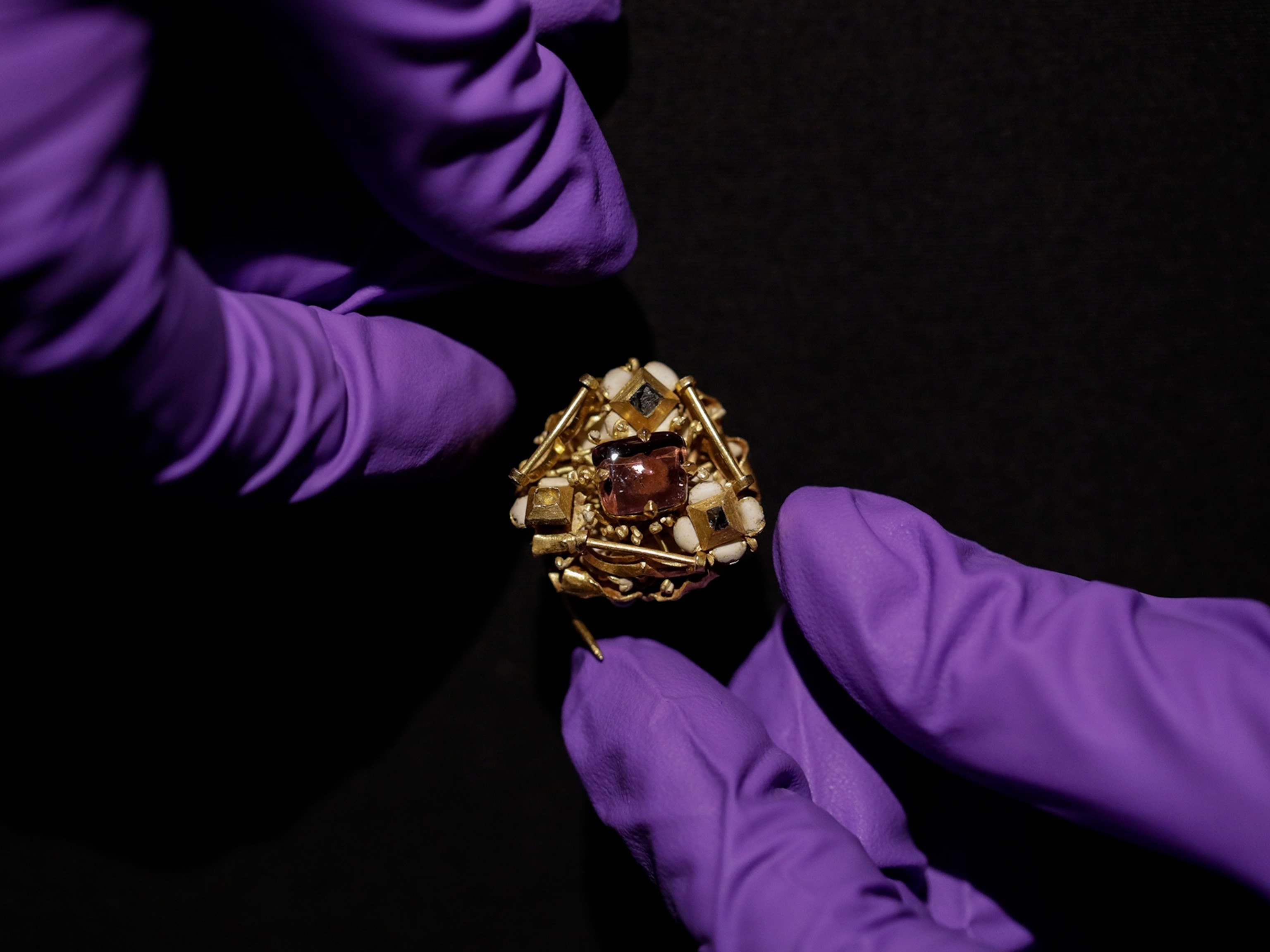

But what made this particular Roman house so special were the belongings of the person who lived there in the early third century. A spectacular array of some 150 surgical instruments, made of bronze and iron and manufactured between the first and third centuries A.D., were found among the remains. This was clearly the home of a Roman surgeon. The tools, which would once have been stored in cases and boxes, form the most complete set of surgical instruments ever found from the ancient Roman world.

The archaeologists also found mortars that must have been used in the preparation and storing of drugs. The evidence suggests that the house functioned as a private clinic, or taberna medica, of the early third century, containing both study space and a medical consulting room. They dubbed it the Domus del Chirurgo—the Surgeon’s House.

(How ancient remedies are changing modern medicine.)

Tools of the trade

A good man

At the heart of this taberna medica was a room paved with a mosaic depicting the mythical Greek hero Orpheus. In this room archaeologists discovered most of the surgical instruments. They also found medical paraphernalia in the cubiculum next to the Orpheus room and in the entranceway. And it was there, on a wall, that archaeologists found an intriguing graffito. The inscription in Latin read:

Eutyches

homo bonus

hic habitat.

Hic sunt miseri.

This translates as: “Eutyches, a good man, lives here. Here are the miserable ones.” It seems reasonable to hypothesize that the text was scratched onto the wall by a sick person being treated by a doctor called Eutyches.

Researchers believe that the doctor trained in Greece and Asia Minor where, in addition to gaining medical knowledge, he acquired cultural artifacts that he took with him to his residence in Ariminum. This would explain the presence of objects outside the city’s typical trading circles. These include a panel of fish in glass paste thought to be from what is now Turkey, a bronze votive hand associated with the cult of Jupiter Dolichenus, and a statue of Hermarchus, a Greek Epicurean philosopher.

The sophisticated surgical instruments found in the house suggest that Eutyches, if that was indeed his name, had specialized in treating trauma wounds and performing surgery. It is therefore likely that he acquired at least part of his training as a military doctor in the camps, and on the battlefields, of the Roman Empire.

(This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?)

An abrupt end

In the mid to late third century, fire razed the Surgeon’s House along with much of northern Ariminum. Ancient authors record that during the reign of Emperor Gallienus (jointly with his father from A.D. 253– 260, then alone from A.D. 260– 268) Germanic tribes made incursions into the Italian peninsula, so the fire at Ariminum may have been the result of confrontation with these invaders. Weapons at the site dating to that period strengthen this hypothesis. The roof of the house collapsed and the adobe walls fell in, burying the interior under a layer of rubble. The city of Rimini came under Byzantine and Frankish control, and it was fought over during the Italian civil wars of the Renaissance. Despite these upheavals, the rubble layer kept this surgical time capsule intact for almost 2,000 years. Since 2007, the public has been able to visit the Surgeon’s House. Together with the great arch and bridge, is now counted among Rimini’s greatest Roman treasures.

(The gory history of Europe’s mummy-eating fad.)