This ancient Silk Road town was almost lost to time

Dandan-Oilik was once a thriving complex packed with Buddhist temples in the Taklimakan desert. What do we know now about this abandoned ancient enclave?

When geographer Sven Hedin set out from the city of Khotan (today Hotan) in western China, he expected to find ruins from an ancient town—but much more lay hidden in the desert sands.

The name of Khotan resonated with Western explorers in the 19th century because famous Venetian explorer Marco Polo visited it in 1274. In his writings, Polo noted Khotan’s wealth as an outpost on the Silk Road, the route that once carried trade between China and the Mediterranean world.

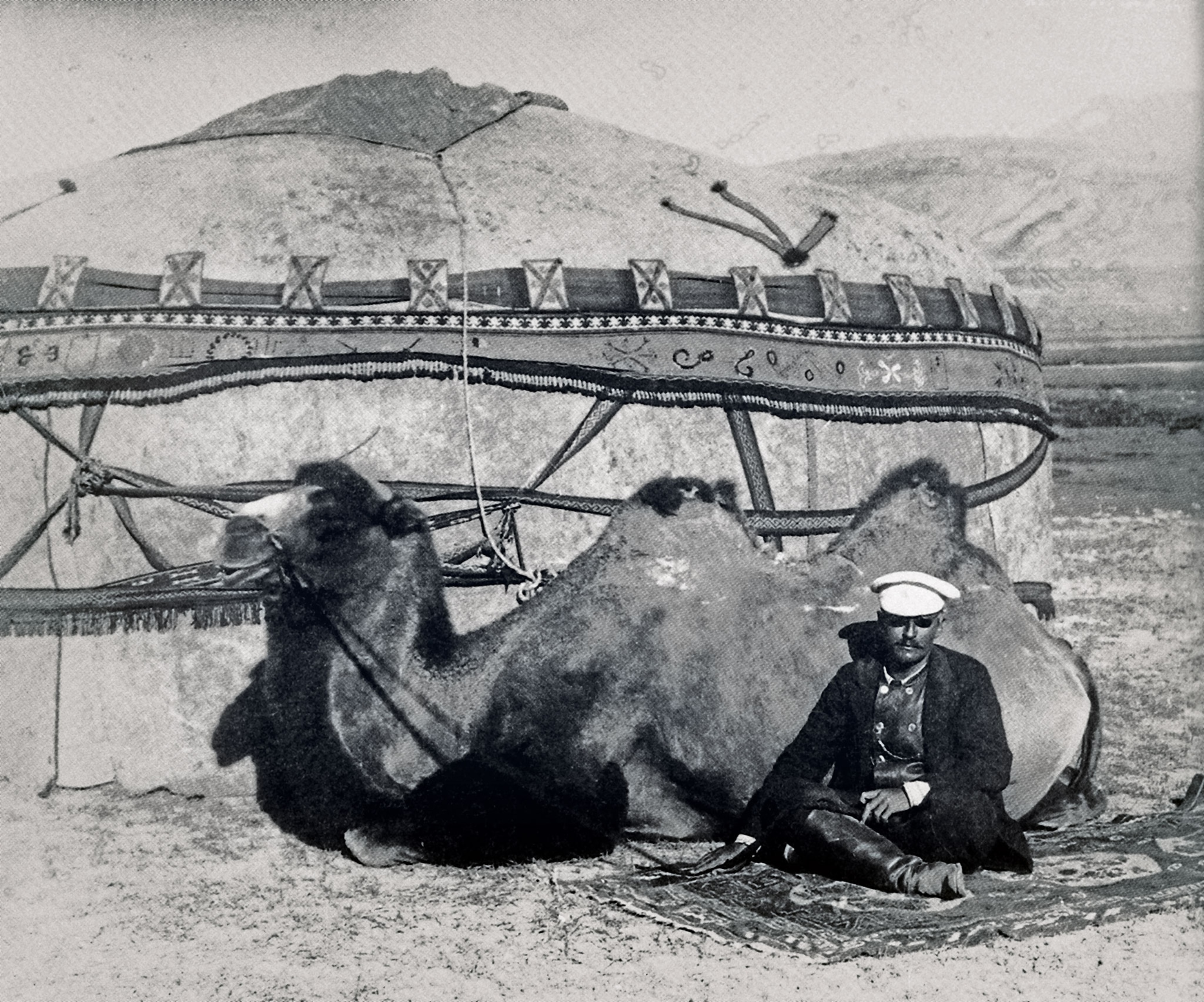

On January 14, 1896, a caravan left from the city. The five-man party was accompanied by mules and loaded with provisions to last 50 days. Riding ahead, perched on a camel, was their leader, Hedin.

Nicknamed “the Stanley of the Central Asian deserts” (after explorer Henry Morton Stanley), the Swedish-born Hedin was a polymath and intrepid adventurer. On arriving in Khotan, he overheard men talking of a ruined town out in the desert and immediately hired them as guides to lead him to the ruins.

(Lost Silk Road cities were just discovered with groundbreaking tech.)

A town under sand

For several days, Hedin and his companions followed the western bank of the Yurungkax River before managing to cross it at a frozen ford. Soon after, they entered the immense Taklimakan Desert with its treacherous, shifting dunes.

From there, their progress became as slow as it was arduous. Six hours walking a day was the most they could endure as they negotiated the high dunes, spurring on their reluctant beasts of burden. Hedin, meanwhile, made notes in his field diary, which later became the basis of his memoirs.

On January 23 the party came to a depression in the desert “abounding in köttek, i.e. dead forest,” Hedin wrote. “Short tree stems and trunks, gray and brittle as glass, branches twisted like corkscrews from the drought.” Hedin, well versed in geography, deduced that they must be on the ancient course of a river called the Keriya-daria, an area that had once been fertile enough to support habitation. Hedin’s guides told him that the ruins they were looking for were nearby. Fragments of pottery corroborated this.

The next day they left the camp and headed to the ruins, Hedin’s men carrying spades and hatchets. Of all the sites Hedin had seen in his expeditions across Asia, none resembled what he saw there. The settlement whose ruins lay before him had been built using a framework of poplar trunks, which gave the buildings a distinctive whitish color. For this reason, the place had become known by locals as Dandan-Oilik, meaning “houses of ivory.”

Wealth and faith

As he made his way through the site, Hedin discerned the outline of square- and oblong-shaped buildings, the interior of each divided into several rooms.

Poles up to 10 feet high were still standing where they once would have supported a roof or even a second floor. The group found traces of many dwellings, covering an estimated area of about one and a half square miles.

But it was impossible to draw up a plan of the town because the patterns of streets and squares were hidden under the sand dunes.

Hedin knew all too well that he lacked the means to investigate further. “Excavating in the dry sand is desperate work,” he wrote. “As fast as you dig it out, it runs in again and fills up the hole. Each sand-dune must be entirely removed before it will give up the secrets that lie hidden beneath it; and that is a task beyond human power.”

Nevertheless, Hedin acquired a general idea of what the ancient enclave would have been like. Musing on its erasure by the dunes, Hedin referred to it as “this God-accursed city, this second Sodom in the desert” and believed, erroneously, that it was some 2,000 years old.

(In Tajikistan, discover the ruins of a once mighty Silk Road kingdom.)

Revealing images

Most remarkable of all Hedin’s findings were the exquisite Indo-Persian-style paintings decorating some of the interiors. Hedin identified these structures, larger than the rest, as Buddhist temples.

The paintings flaked off at the slightest touch. Hedin sketched them as best he could and, in keeping with the colonialist mindset of the era, took other objects such as sculptures and stucco reliefs, writing later: “All these finds and many other relics, were wrapped up carefully and packed in my boxes; and the fullest possible notes on the ancient city ... were entered in my diary.”

Despite the wonders he had glimpsed, Hedin decided to move on: “For me it was sufficient to have made the important discovery, and to have won in the heart of the desert a new field for archaeology.” The morning after writing this, he left Dandan- Oilik and plunged back into the shifting sands of the Taklimakan Desert.

Around the same time that Hedin was undertaking his desert journeys, a young Hungarian-born Briton, Marc Aurel Stein, was making a name for himself as a scholar of Persian and Sanskrit.

In 1898 Hedin’s memoir Through Asia was published. The book had a huge influence on Stein, then in his late 30s. Two years later, he embarked on the first of four expeditions to Central Asia. Following in Hedin’s footsteps, Stein arrived in Khotan in winter 1900. There, his guide showed him objects from the site, including fragments of frescoes from temples, some with Brahmi script (a writing system of ancient India).

Energized by this proof, Stein set off through the freezing wastes of the Taklimakan to arrive at Dandan-Oilik in late December 1900. His extensive knowledge of Buddhist art and scripture helped him establish the site as an abandoned oasis town that had thrived from the sixth century A.D. But what had happened to the town that forced its citizens to abandon its bustling streets and splendidly adorned temples?

(The controversy behind this Silk Road city’s ancient wonders.)

Oasis trade hub

After several weeks, Stein established that as many as 14 Buddhist temples had once dominated the town. They consisted of a cella (the sacred part of a temple) at the core, which was nested inside a larger structure.

Among the artworks were magnificent stucco figures of Buddhas and well-preserved paintings on wooden boards. To Stein’s excitement, he recognized the themes of some of the paintings, including one illustrating the silkworm legend. This tells the story of a young Chinese noblewoman wed to the king of Khotan. Flouting the rule that silkworms cannot leave the Chinese heartland, the young bride smuggles mulberry seeds and silkworms to her husband in her headdress.

The legend deftly links the town’s Buddhist piety and its prosperity on the Silk Road. Among the last datable items that Stein found were eighth-century coins. Stein theorized that the town’s decline must have been tied to China losing administrative control of the region in that period. Later studies, including a joint China-Japan excavation in 2002, corroborated this. In the 700s, as geopolitics changed with the rapidity of the dunes, the thriving town, with its trade, art, and temples, was abandoned, and the sands swallowed the glory that had been Dandan-Oilik.