These 5 ancient cities once ruled North America—what happened to them?

Teotihuacan, Cahokia, and other metropolises featured striking religious centers, multifamily dwellings, and burial mounds, only to vanish. Archaeology is slowly revealing their splendid pasts.

Long before Europeans arrived in the New World, indigenous Americans raised pyramids and palaces, temples and tombs in booming cities whose sizes rivaled those in Europe. Citizens of Cahokia traded with their Mesoamerican neighbors; the enigmatic people of Teotihuacan had ties throughout Central America; and Spiro Mounds is said to have equaled the power and sophistication of the Inca and Aztec. Today, investigators are still uncovering major urban centers that testify to the complexity of America’s first megalopolises.

(Explore the palaces and tombs of these "lost cities" across the Americas.)

Teotihuacan: epicenter of architecture and art

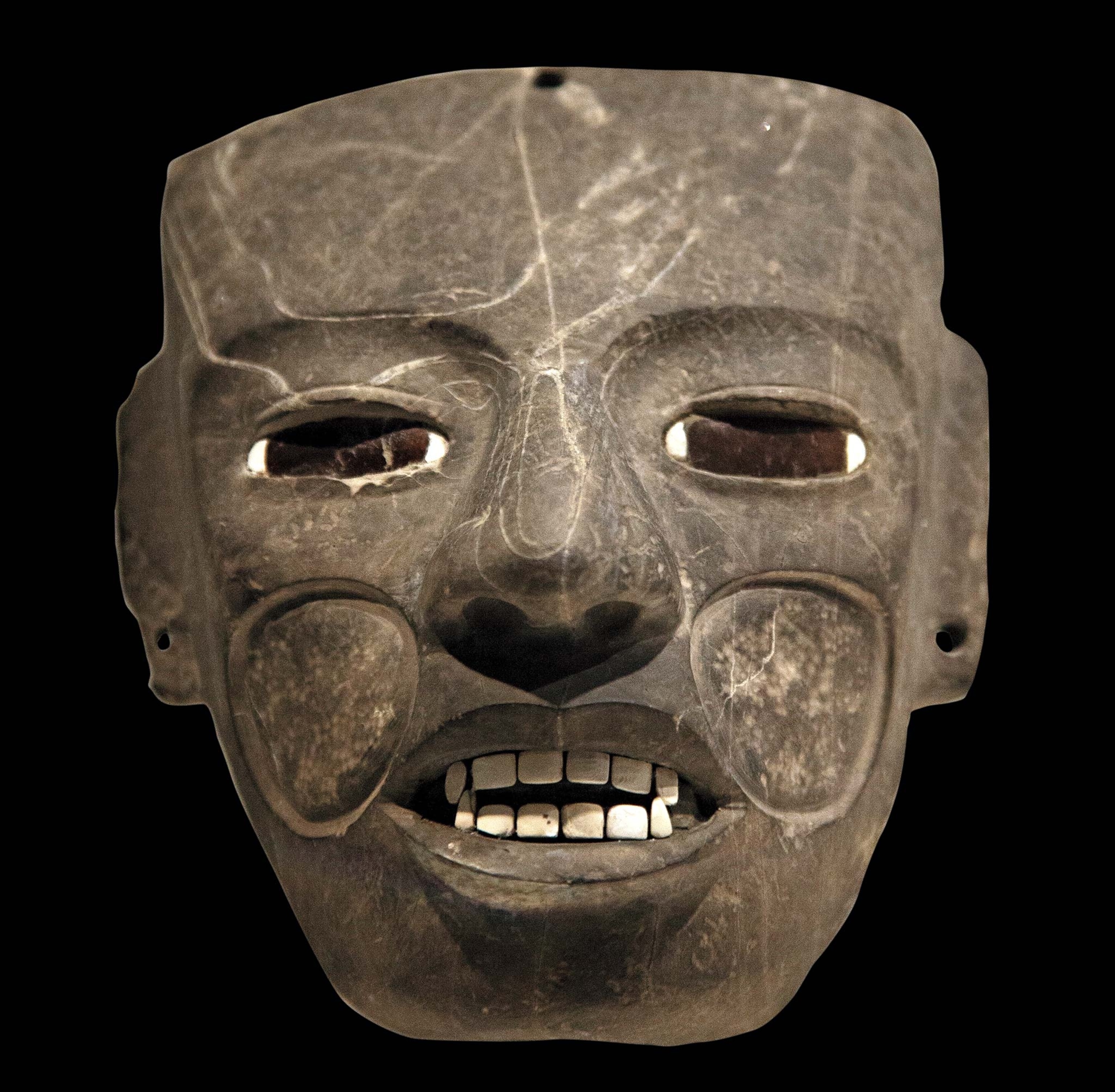

At its peak in 400 A.D., Teotihuacan, just 30 miles northeast of present-day Mexico City in the Valley of Mexico, reigned as perhaps the largest city in the Americas. More than 100,000 Teotihuacanos dwelled among an impressive array of palaces, temples, plazas, avenues, and thousands of apartment buildings within 8 square miles. Along with priests, soldiers, and merchants, Teotihuacan had a flourishing artist community whose wares influenced cultures throughout Mesoamerica. Today it’s Mexico’s most important archaeological site.

(These ancient peoples were the innovators of their times.)

Significant enduring structures include the imposingly tall Pyramid of the Sun, believed to have venerated a deity within Teotihuacan society; and Pyramid of the Moon, used for ritual sacrifices of animals and humans—proof found beneath it include the bodies of pumas, eagles, wolves, and 12 humans, 10 of them decapitated.

Sometime around A.D. 750, the central city burned, possibly at the hands of invaders, and Teotihuacan never recovered. Just who the Teotihuacanos were, where they came from, and what language they spoke remain a mystery that archaeologists are still working to uncover.

(Archaeologists discover mysterious monument hidden in plain sight.)

Cahokia: cosmopolitan trade center

Around 1000 A.D., a complex metropolis thrived in the rich floodplain near present-day St. Louis, Missouri at the confluence of the Mississippi, Missouri, and Illinois Rivers. Known as Cahokia, it was the largest city north of Mexico, with an estimated population between 10,000 and 20,000—rivaling that of European cities of the era. At least 100 raised structures dominated the city, some topped with houses and other buildings, while others were used as burial mounds. The largest building, known as Monks Mound for the Trappist monks who lived nearby in the 1800s, is a terraced structure rising 98 feet into the air. Its base, occupying 14 acres, is larger than the footprint of Egypt’s Great Pyramid of Khufu.

Little is known about this ancient civilization’s rulers or history, but, based on scholarly research, it was a cosmopolitan center of trade, crafts, and architecture. Mississippian people exchanged goods with others as far north as modern-day Wisconsin, and possibly with Mesoamerican cultures to the south.

Beginning around 1175, something or someone began to threaten the Cahokians, judging by the protective wooden palisades they set up around the city center. A cooling climate and stress on the local environment might also have made the city less livable. By 1350 or so, the Cahokians had dispersed.

(Archaeologists want to know why this American Indian metropolis was abandoned.)

Robots in the tunnels

Chaco Canyon: capital of formidable women

Rivaling the Cahokian culture in complexity, if not in size, was the Chaco culture well to the west, in what is now New Mexico. From the 800s into the 1200s, ancestral Puebloan people lived in more than 150 settlements around Chaco Canyon, occupying sprawling stone mansions with hundreds of rooms—the most important of which is Pueblo Bonito, the center of the Chacoan world. They farmed, traded, and conducted religious ceremonies and spread out across a well-tended road network for hundreds of miles to the west, north, and south. To water their crops of corn, squash, and beans, locals harnessed the intermittent flow of local streams through canals and ditches. Traders brought in exotic goods such as scarlet macaws and cocoa from Mesoamerian peoples to the south.

(Fingerprint study upends ideas about "women’s work" in ancient America.)

The Chacoan people had no written language, so much of what is known about their society comes from burials. One burial room, for instance, held 13 presumably high-ranking bodies surrounded by thousands of turquoise beads, shells, bowls, and pitchers. DNA analysis showed that many of the individuals were related through their mothers or grandmothers. Power may have been passed down through the maternal line.

By the 13th century, the Chacoans began to leave for other parts of the Southwest. It’s not known exactly why, though it’s possible severe drought forced them out.

The gambler god

(How turquoise became synonymous with New Mexico.)

Spiro Mounds: center of wealth and power

In 1933, a group of gold prospectors stumbled across a burial chamber near Spiro, Oklahoma, that had been closed for 500 years. Inside, they discovered stunning treasures including engraved conch shells, pearl and shell beads, large human effigy pipes, and brightly hued blankets and robes. Newspapers dubbed the find an American “King’s Tut tomb.”

Twelve mounds, the elite village area, and part of the support city have been uncovered, all that’s left of a prehistoric power that once equaled the size and sophistication of the Aztec and Inca. The Spiro people ruled over the Mississippian culture over nearly two-thirds of what is now the United States, including Cahokia (now East St. Louis), Moundville in Alabama, and Etowah in Georgia.

The location became a permanent settlement around A.D. 800 and was used until about A.D. 1450. At its zenith, some 10,000 people resided here. Artifacts point to an extensive trade network (including copper from the Great Lakes and a conch shell from the Gulf of Mexico), highly developed religious activity, and an advanced political system. Large earthen platforms and burial mounds were highlights of the agricultural communities. Leaders built their homes on top of the previous chief’s, so that the higher the mound, the more prestige the current leader held.

(This Native American society was once as powerful as the Aztecs and Incas.)

The Spiro people mysteriously disappeared by 1500, perhaps due to an extended drought and/or political infighting.

Etzanoa: long-lost city

Legend speaks of a vast ancient metropolis of more than 20,000 citizens, ancestors of the Wichita Nation, flourishing at the confluence of the Walnut and Arkansas Rivers, near present-day Arkansas City in south-central Kansas. The citizens of Etzanoa, referred to as the “Great Settlement” by other indigenous groups, lived in houses shaped like big beehives, each holding around a dozen people with lush gardens between the homes. During the winter months the community would follow the bison herds and would erect tipis as temporary dwellings while traveling. They had strong artisan traditions and an extensive trade network that reached as far as Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital.

Starting in the late 16th century Spanish conquistadores on a quest for gold contacted the group living in this region. According to Spanish accounts, the two groups were friendly, even sharing corncakes. But in 1601, the Spanish, led by Juan de Oñate, took hostages and the residents ran away. They returned, attacking the Spanish, who in turn fired four cannons. And then they disappeared.

(At the crossroads of the Trail of Tears, Little Rock reckons with its history.)

French explorers who passed through in the 1700s did not find a city, despite the legend. Archaeologists surmise that smallpox and other diseases killed most of the original settlers. Etzanoa remained a mystery until 2016, when a local teen found a cannonball linked to the 17th-century battle. The long-lost city—at least its remains—had been rediscovered.

To learn more, check out Lost Cities of the Ancient World. Available wherever books and magazines are sold