How medieval fortresses were built for war

In the ninth and tenth centuries, castles were often built of wood and easily burned down by enemies. As unrest spread across Europe and warfare began to change, castle designs had to adapt.

The human instinct to seek protection behind walls or trenches or on top of natural elevations goes back millennia. But it was during the Middle Ages, and in response to the evolution of weaponry and warfare, that this drive led to the building of fortified castles. In this golden era of their construction, castles reached a degree of perfection and complexity unparalleled in history.

The first medieval fortifications were very different from the imposing castles that appeared later. In the ninth and 10th centuries, the castles being constructed across Christian Europe were generally wooden structures built on top of artificial mounds that, after the Norman conquest, were called mottes. Typically, the motte would be surrounded by a defensive moat. The earth excavated to form the moat was then used to create defensive embankments that were topped with a wooden palisade. A wooden drawbridge provided access across the moat.

By the 11th and 12th centuries, these mottes were proliferating across France and Anglo-Saxon and Norman England. As the Reconquista military campaign that European Christian kingdoms waged against the Muslim kingdoms (who had been occupying much of the Iberian Peninsula since the early eighth century) advanced, similar mottes were erected on the plains of Castile between the 10th and 11th centuries. One was the Mota de Muñó in Burgos, Spain, which became the center of a busy community in the 10th and 11th centuries. It was common for towns to develop around these castles, as inhabitants benefited from the protection offered by the moats, raised earthworks, and wooden palisades.

(Medieval robots? They were just one of this Muslim inventor's creations.)

Motte and bailey

The wooden forts that topped these mottes were soon replaced by large, usually square, stone towers. This central tower of a medieval castle was called a keep in English, a donjon in French, a bergfried in German, and a maschio in Italian. But its Spanish name, torre del homenaje (tower of homage) speaks to one of its functions. From the middle of the 10th century, after the fall of the Carolingian Empire, imperial power in western and central Europe was being replaced by a large number of feudal lords, who were practically sovereign in their territories. The towers of homage provided places where vassals could come to pay obeisance to their lords.

The stone castles that we recognize today as emblematically medieval appeared from the 11th and 12th centuries onward, having developed out of the comparatively simple earlier fortifications. The main impetus for this evolution from simple wooden keeps to formidable stone castles was the changing nature of warfare. Other than a few pitched battles, medieval warfare tended to focus most of its operations on the attempt to control the fortresses of a given territory. As the techniques and technology of those mounting sieges became more sophisticated, castle builders were driven to new heights of ingenuity. Castle design began to incorporate a series of concentric defensive walls. At the center of these, the old keep would be enlarged to become a last defensive stronghold. These imposing-looking fortresses proved remarkably effective in resisting assaults and invasions.

Building a castle

The first task of the castle builder was to choose a suitable site. The castle’s position in the landscape with respect to other fortified enclaves was key. It was essential to have a clear view of other fortifications in order to receive strategic messages—fiery beacons by night or smoke signals by day, which could warn of imminent danger, such as the incursion of an enemy army.

The locale chosen had to command the surrounding area, especially strategic elements such as roads, bridges, and fords, while also offering access to agricultural and other resources. Other factors to consider were the availability of building materials and a water supply for filling wells, pools, and cisterns. The castle’s defenders needed to stockpile enough food and water to allow them to hold out in the case of a prolonged siege.

The next task was to secure the outer perimeter. This meant building defenses around the access points as well as strategic locations, such as bridges and water sources. If large enough, a moat made it difficult for the enemy to get close enough to the walls to do damage with projectiles or battering rams. In places with dry climates and rocky terrain, the moats were usually dry, narrow, and deep. In temperate climes and in flat areas with claylike soil, wide, shallow moats were dug and flooded with water. In the Iberian Peninsula, the Calatrava la Vieja Castle, which was fought over by Moorish and Christian forces throughout the 12th century, was built to turn the Guadiana River into a natural moat on its north side. A ditch dug around the rest of the castle was filled with water from the river.

Beyond the moat stood the outer walls of the castle complex. Sometimes several walls were erected around the main enclosure, usually arranged concentrically. This meant that, even if the enemy managed to break through the first line of defense, they could at least be ambushed before they reached the second. The walls were built high, making it difficult to fire arrows and other projectiles into the castle from outside. The height also served to deter climbers who might try to slip in by stealth at night using ladders and take the castles by surprise. While challenging, this type of sneak attack was, apparently, not uncommon.

According to the Andalusian chronicler and historian Ibn Sahib al-Salat, writing sometime before the end of the 12th century: “On rainy and very dark nights,” Gerald the Fearless, a Portuguese Christian adventurer, “prepared his very long wooden ladders” and scaled castle walls and tower “in person.” Gerald was said to have climbed into numerous Almohad castles in present-day western Spain and Portugal by using this method.

This mode of attack was such a concern that the law code Las Siete Partidas, written in the mid-13th century by King Alfonso X of Castile, warned that castle walls must be built tall enough so that anyone attempting to enter via a ladder would be deterred.

(This mighty medieval woman outwitted and outlasted her rivals.)

None can enter

Although the keep had pride of place as a castle’s main fortified tower, smaller towers were attached to the fortress walls and also rose above them. Square, circular, or pentagonal in shape, the smaller towers protected the base of the walls and acted as buttresses, strengthening the fortification. Any opening in the castle wall was a weak point, so any arrow slits or windows that did exist were kept small and high up.

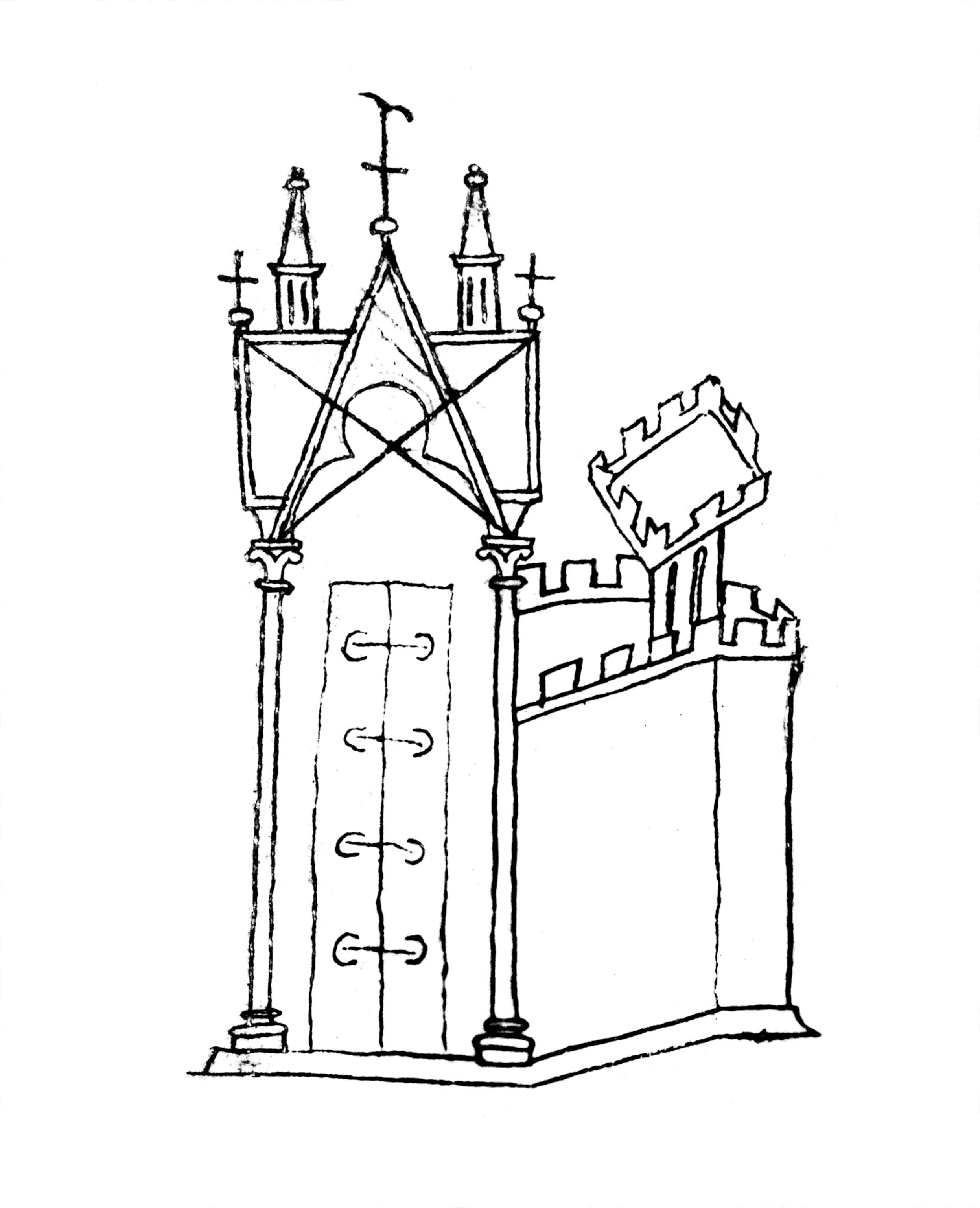

The main entrance to a castle complex had to be large enough to allow access to the enclosure, but since any opening created a vulnerable spot, both builders and garrisons took special care to reinforce the defenses of a castle’s entryway. Castle gates would be made of heavy wood, often reinforced with metal plates and fastened with strong bolts. Backup came in the form of a portcullis, a heavy metal or wooden grille that could be lowered to block the entrance. In addition, the gateways usually had a small gatehouse, the better to see, trap, and counterattack any invading forces. Some castles had an enclosed space called a barbican in front of the gate. Would-be attackers wanting to reach the entrance had to risk entering this space, where they might be ambushed. The same purpose was served by bent entrances, where the passageway through the gate included at least one 90-degree turn.

Strong stone walls and cleverly laid traps were not enough to keep a castle wholly safe from attack. Through smart design, the building itself had to become a complex war machine. Instruments of defense were concentrated in the chemin de ronde, a protected, elevated walkway high up behind the battlements. This walkway connected all parts of the castle, was sometimes covered, and was protected by a parapet, a low wall above the main wall, with openings through which one could see—and shoot arrows or other weapons.

From this shielded vantage point, defenders could send down a lethal rain of projectiles on their attackers. They would hurl rocks, boiling water or wine, and hot

sand, which penetrated cracks in the assailants’ armor. Incendiary projectiles such as firepots filled with oil or tar could wreak havoc in the approaching enemy lines. The battlements, arrow slits, and loopholes provided protected openings from

which to shoot arrows. As artillery developed in the 14th and 15th centuries, cannons were fired from here too. Murder holes (or meurtrières) above doors and cut into the ceilings of gatehouses allowed the defenders to drop projectiles or burning liquid down onto any attacker who managed to get that close.

(What made Oxford's medieval students so murderous?)

By exploiting the castle’s potential as a killing machine, a small number of defenders were able to keep large contingents of enemies at bay. As a result, full-force assaults were infrequent, although they could occur when the attackers had sufficient resources, men, and siege engines. One such assault took place in 1147, when an expeditionary force of European Crusaders on their way to the Second Crusade arrived at the gates of Lisbon, a city then in Muslim hands. There, the Crusaders deployed battering rams, mangonels (a siege weapon for catapulting projectiles), and mobile siege towers to launch an attack. They also used a technique called undermining, or digging tunnels under the walls then setting fires in them to cause the walls, which had timber frames, to collapse. Within four months, the Crusaders had forced the surrender of the city.

Given the cost and scarcity of manpower and resources, however, raiding parties were often unsuccessful. It was more common for medieval armies to blockade or encircle a castle with the aim of exhausting the defenders into submission via siege. This type of operation could be dragged out for many months, as happened in the siege of Algeciras in southern Spain. The military operation began in 1342 and lasted 21 months, as Christian forces under Alfonso XI besieged the Muslim-held city. It was a complex operation involving numerous forces and innovative war machinery on both sides.

The Muslim defenders were armed with rudimentary cannons the Spanish called truenos (Spanish for “thunder”) because they made a terrifying noise. To strengthen his attack, Alfonso called for the delivery of engeños, a kind of catapult, to breach the walls of the city.

(Was the medieval order of Assassins a real thing?)

Every night, those inside the city tried to patch up the damage wrought during the day. Such was the quantity of projectiles launched against the walls of Algeciras that almost a century and a half later, in 1487 during the conquest of Granada (1481-1492), Ferdinand the Catholic sent a contingent to the city to gather up all the stone balls they could find for reuse in the bombardment of Málaga.

Life on the inside

The community living within the castle complex was sometimes quite large, although numbers varied greatly depending on the place and period. For example, the Templar Crusader castle of Safed in northern Israel, which was rebuilt around 1260, had a capacity for 2,200 soldiers in wartime and a permanent garrison in peacetime of 1,700 men. On the other hand, in the 15th century, many castles run by Spanish military orders saw their communities dwindle to just one or two knights and a few servants. Provided that they were far away from the border with al-Andalus, the area of the Iberian Peninsula under Muslim rule, these castles had little to threaten them, and, therefore, little need for defenders. Even before this, in 1271, King James I of Aragon had authorized the warden of the strategic fortress of Biar in Alicante, on the border with Castile, to remain there with just 12 men, one woman, one mule, and three dogs.

A new star rising

Whether the castle community was large or small, its members needed space to live; to store food, water, and livestock; and to carry out domestic and artisanal activities. The oldest fortresses, those located in volatile border areas, or those that had faced the vicissitudes of war were generally not very comfortable environments given their military emphasis.

(Majestic medieval churches ascended along Christian pilgrims' paths.)

Other castles, meanwhile, offered all kinds of comforts to their occupants, including latrines, cisterns, wells, hearths, kitchens, ovens, and, of course, chapels. As they served as centers for collecting feudal rents, generally paid in kind, some complexes had extensive storerooms for keeping these goods. It was not uncommon for castles to have their own bakeries, distilleries, and forges.

Some major fortresses included large reception rooms, where kings, nobles, and prelates could flaunt their status. While the furniture in these rooms tended to be austere, the decoration was elaborate. The walls and ceilings were often adorned with paintings or hung with tapestries which, as well as being decorative, provided insulation from damp and drafts.

(Terrifying visions of the Apocalypse revealed the fears of medieval Spain.)

Decline and fall

For over 500 years, medieval castles provided defense and bragging rights for their inhabitants. But by the 16th century, the development of modern artillery had rendered many medieval castles obsolete. Cannonballs had the power to damage castle walls, making their design impractical and ineffective.

Over time, the traditional castle design with high walls surrounding a stone keep perched high on a motte was slowly replaced by a new model of fortification built to withstand cannon fire. These new fortifications were cannon-proofed with bastions and thick angular walls that were sunk into the ground.

As for the existing castles, some were converted into palaces, lightly fortified residences with large windows knocked into the previously impenetrable walls, added facilities, and perhaps even gardens. The Alcázar de Segovia in Spain, for example, was built as a fort in the 12th century and later became a palace for the Castilian monarchs. Many old castles, however, were abandoned. In modern times, some have been converted into museums and monuments—Caen Castle is now home to the Normandy museum, and Scarborough Castle, while in ruins, is a tourist attraction in North Yorkshire. Having withstood violent battles, technological advances, and the weight of several centuries, these crumbling but still majestic structures stand as silent witnesses to, and symbols of, an era in which they played a central role in the history of Europe.

(This country has the most castles in Europe.)