500 years after Aztec rule, Mexico confronts a complicated anniversary

Was the 1521 surrender of the great Indigenous empire to the Spanish crown a triumphant conquest, an existential tragedy—or even a genocide?

The remains of a massive cypress tree sits inside a small plaza in Mexico City, surrounded by fencing and illuminated by four spotlights at night. An old sign explains its significance: “This is the tree where Hernán Cortés wept after being defeated by the Aztec defenders.”

We Mexicans call it El Árbol de la Noche Triste, or The Tree of the Sad Night, and learn about it since grade school from government-issued history textbooks. The story goes something like this: In March 1519, a couple of hundred Spaniards, led by a stubborn but resourceful man with some legal training named Hernán Cortés, appeared on the Gulf of Mexico coast. They established contact with the mighty Aztecs of central Mexico and, after exchanging messages and gifts, made their way to the Valley of Mexico and the Aztec stronghold of Tenochtitlan (downtown Mexico City).

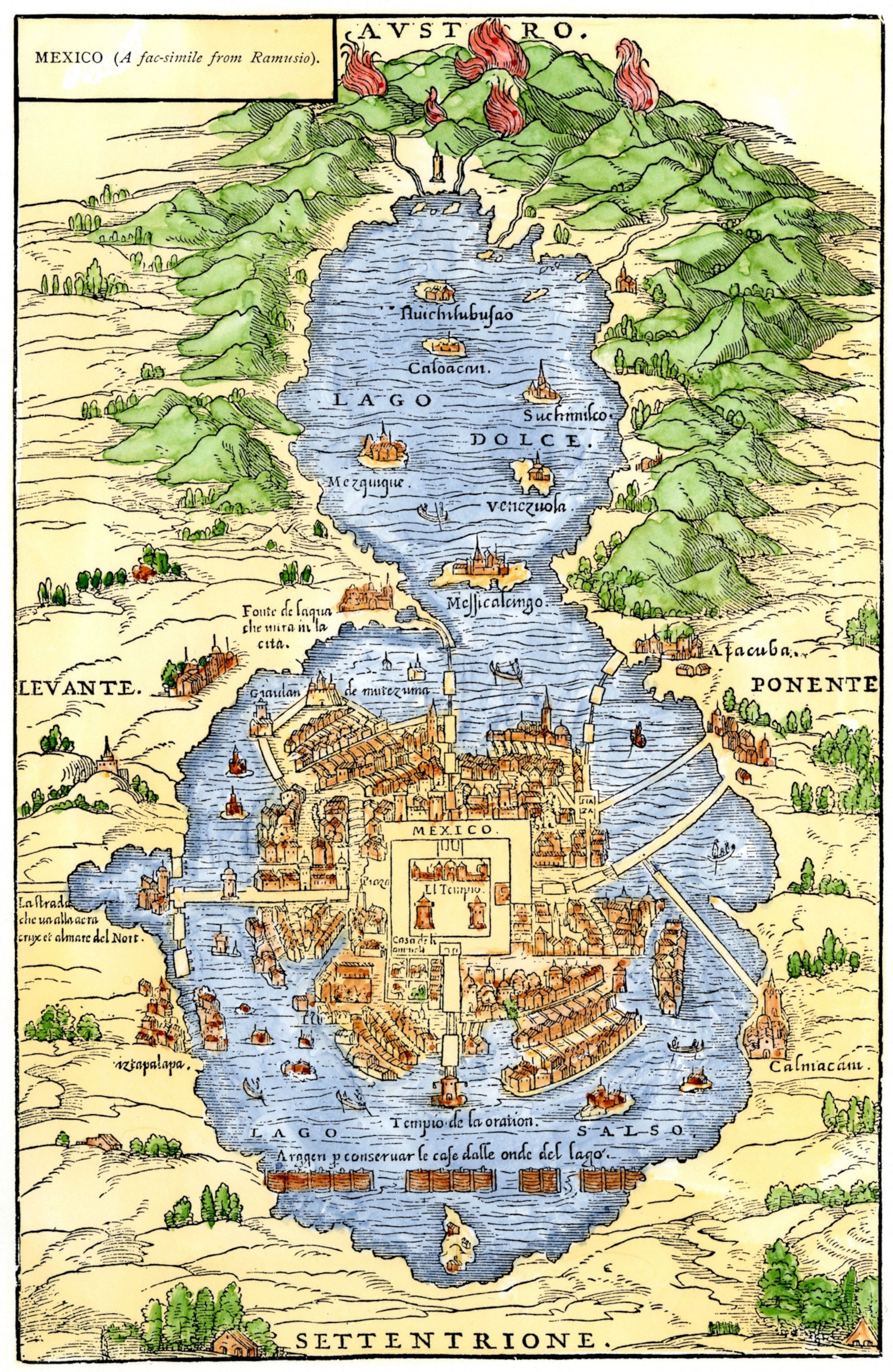

Remarkably, the Aztec tlatoani (emperor) Moctezuma initially welcomed the strangers. The Europeans were thus able to wander freely, according to our textbooks, marveling at the lavish buildings and floating gardens of a city built on top of an island in the middle of five interconnected lakes. From the top of Tenochtitlan’s grandest temple, the Templo Mayor, the visitors gazed out at dozens of city-states spreading all around the surrounding lakeshores. Some of these city-states had once been rivals of the Aztecs, but Tenochtitlan had become the dominant power by the 1500s.

Read more about the complex Aztec alliance.

Yet the newcomers outlasted their welcome. Prompted by mistrust and lack of understanding, on May 22, 1520 the Spanish launched an unprovoked attack on a group of unarmed Aztecs during a ceremony at the Templo Mayor. The formidable Aztec warriors fought back, driving the intruders from their island city and inflicting heavy casualties along the way. More than half of the Spanish contingent may have perished during the chaotic retreat. At some distance from Tenochtitlan, Cortés and his followers finally paused in a cypress grove to catch their breath, where the defeated Spanish leader sat at the base of a tree—perhaps the famous Árbol—and wept, as our textbooks and history classes would have it.

This Aztec victory proved temporary, however. The following year, Cortés returned with an army of Spanish soldiers and tens of thousands of Indigenous allies. After a long siege that cut the fresh water supply to the island, and following a multi-pronged attack that included ships assembled on the lakeshores and equipped with artillery pieces, Tenochtitlan finally surrendered to the Spanish and their allies on August 13, 1521, exactly 500 years ago today.

This summer, I visited the Tree of the Sad Night and found city workers preparing for the fateful anniversary. At the plaza, I ran into a working crew anchoring a gleaming new sign that identified the famous tree as the Árbol de la Noche Victoriosa or “Tree of the Victorious Night.” It was a stark change in point of view.

Below this novel Spanish designation, the sign offered an even more contrasting rendition in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs that is still spoken by more than a million Indigenous people in central and southern Mexico: “Quautli in Yohualli Paquiliztli, nican ochoca” or “Tree of the Happy Night, here he cried.”

Finding the right words

The usual textbook portrayal of a band of brave Europeans toppling the most powerful Indigenous empire in the Americas may have some cinematic qualities but has always been suspect, particularly to professional historians like myself. Scholars very seldom speak with one voice, but there is broad consensus that understanding the events of 500 years ago as a binary clash between “Spaniards” and “Natives” is simply wrong.

Discover how artificial intelligence is helping to preserve Aztec culture.

Instead, the war that unfolded in 1519-1521 involved multiple and fiercely independent Mesoamerican city-states such as Cempoala, Tlaxcala, and Texcoco, organized in ever-shifting coalitions, one of which included a handful of Spaniards. Cortés and his conquistadors may have represented at the most one or two percent of the total forces on the field.

Insights such as this one are making present-day politicians and the public at large cast about for new ways to understand and refer to what happened that summer of 1521. Was it the Conquest of Mexico? A Mesoamerican war? An encounter of two worlds? A genocide?

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit Mexico hard, forcing the closure of museums and exhibits that in other circumstances would have been natural venues for the quincentennial. Still, federal and city authorities have organized commemorative events, especially on the zocalo, or main plaza, of Mexico City where a 45-foot model of the Templo Mayor complete with state-of-the art illumination will be unveiled, just a couple of hundred yards away from the ruins of the original.

In the meantime, ordinary Mexicans have chosen to remember the anniversary in their own ways. Whether at the Árbol, the Templo Mayor, or elsewhere in Mexico City, I ran into men and women decked out in pre-Columbian paraphernalia, dancing and performing limpias, spiritual cleanses. Some of these performers were there merely to make a living, asking for donations after their dances and charging fees for the limpias. But many of them were also committed to a greater or lesser extent to keeping Mesoamerican—and particularly Aztec—traditions alive. Some of them study Nahuatl, read history, and try to make sense of those long-ago events.

Learn about excavations at the Templo Mayor.

One morning, at the Templo Mayor, men and women were gathering in front of the ruins after having spent the night outdoors, in defiance of a stubborn rain, to honor Cuitláhuac, Moctezuma’s younger brother and a reputed warrior who had ruled Tenochtitlan briefly after Moctezuma’s death. As the rain continued through the morning, they set up a canopy and underneath it laid out candles, copal, food offerings, and flowers. A few Xoloitzcuintli—hairless dogs descended from pre-Columbian breeds that were nearly wiped out by the Europeans—sniffed around the area. To one side, there were banners with Cuitláhuac’s image and yet more flowers. The dancing started around noon, driven by relentless drumming and attracting spectators. During a brief pause, an elderly man walked toward the onlookers and announced, “He never lost a battle to the Spanish.”

Spaniards in the story

Cortés died in Spain in 1547, but his mortal remains were returned to Mexico as he had stipulated in his last will and testament. After various moves, they came to rest at a hospital in downtown Mexico City, merely three blocks from the Templo Mayor. Some historical traditions affirm that it was around these grounds where Cortés and Moctezuma met for the first time.

Cortés himself had founded the Hospital de Jesús as early as 1524 and, remarkably, it remains in operation. This year, however, the building is off limits in spite of its historical significance. “Only patients can come inside because of the pandemic,” a receptionist tersely replied when I asked if I could go inside to see a bust of Cortés that lays discreetly in an interior courtyard.

It is possibly the only public bust of the conquistador in all of Mexico. Ever since Mexico achieved its independence from Spain in the early 19th century, Cortés has become notable for his absence, although he still manages to cast a long historical shadow. Very few streets or places are named after him. About 40 years ago, a statue of Cortés was erected in the neighborhood of Coyoacán, but the local residents complained and threw painting on it. The statue did not last long.

More recently, other Spanish conquistadors have come under similar scrutiny. Just a few blocks away from the Árbol, there is a street called “Puente de Alvarado” or “Alvarado’s Bridge,” named after Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado who, according to the early chronicles, was the one who ordered the unprovoked 1520 attack on the Aztecs celebrating at Tenochtitlan. Yet, earlier this year, Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum indignantly asked, “How is it possible that we have a street named Puente de Alvarado when Alvarado was the principal perpetrator of the massacre at the Templo Mayor?” The thoroughfare is now called “Calzada México-Tenochtitlan.”

Still, 16th-century Spaniards were masters at writing themselves into the story, especially Cortés himself, a born self-promoter. His Second Letter to the Spanish King—published widely in Europe and quoted by historians—is a monument to selective storytelling, exaggeration, and shameless lying. When he wrote his letter at the end of October 1520, Cortés and his followers were still licking their wounds four months after their hasty retreat from Tenochtitlan and the “Sad Night” (now “Victorious” or “Happy”). Nonetheless, the Spanish leader had little trouble boasting about having already won a magnificent kingdom, “so Your Majesty can justly title yourself its new emperor.”

A global turning point

In the decades and centuries that followed that pivotal summer 500 years ago, Spain did come to rule what is now Mexico, Central America, and parts of the United States; and, in the fullness of time, much of the western hemisphere. The most powerful European empire of the early modern era was able to exploit this large region in very tangible ways that ranged from the extraction of minerals and plant products to the outright enslavement of Indigenous peoples. Between 1500 and 1800, around 80 percent of all the silver produced in the world came out of New World mines. Related to this prodigious extractive activity, some 2.5 to 5 million Native Americans were enslaved in the American continent between the arrival of Columbus and the beginning of the 20th century, according to my estimates.

Beyond such terrible consequences for the Americas, the European takeover of America had dramatic repercussions for the rest of the world. Resources extracted from the continent gave Europeans just enough of an edge to lead the industrial revolution and gain ascendancy until quite recently. In the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, parts of China, Japan, and India enjoyed levels of technological and institutional development comparable to those of Europe. Yet the naked exploitation of the Americas—that began in earnest with the takeover of Mexico—enabled some parts of the Old World to grow its population and wealth and pull ahead from the rest of the world.

The Spanish conquest also turned Mexico into a major bridge between East and West. Barely nine months after downfall of Tenochtitlan, Cortés himself established a beachhead on the Pacific coast. “I have started building ships and brigantines to explore all the secrets of that coast,” he wrote to the Spanish monarch in 1522, “and this will undoubtedly reveal marvelous things.” In 1527-1528, Cortés launched an expedition from Mexico to Asia. By the 1560s, annual Spanish galleons connected Asia with the Americas, finally giving rise to the global world that we now know.

National narrative

When I got together with my family and friends in Mexico City, few seemed particularly interested talking about the quincentennial. COVID-19 has caused Mexico’s worst economic contraction since the 1930s, so the conversation naturally veered toward lost jobs, insecurity in the streets, or plans for moving out of the city to greener pastures.

Nonetheless, some of them were intrigued by the sheer proliferation of anniversaries during this fateful pandemic year. While the destruction of the magnificent city-state of the Aztecs in 1521 may not seem worth remembering, Mexicans are also celebrating the end of Mexico’s wars of independence from Spain in September 1821. Five hundred years of la conquista thus coincides with 200 years of la consumación de la independencia; the first a tragedy commemorated in August and the second a party reserved for September.

As if this were not enough, the Mexican president along with Mexico City authorities added a third major anniversary to this calendar year: 700 years since the founding of the Aztec Empire in May of 1321 (even though the date remains controversial, as early sources are vague and sometimes refer to 1325 rather than 1321).

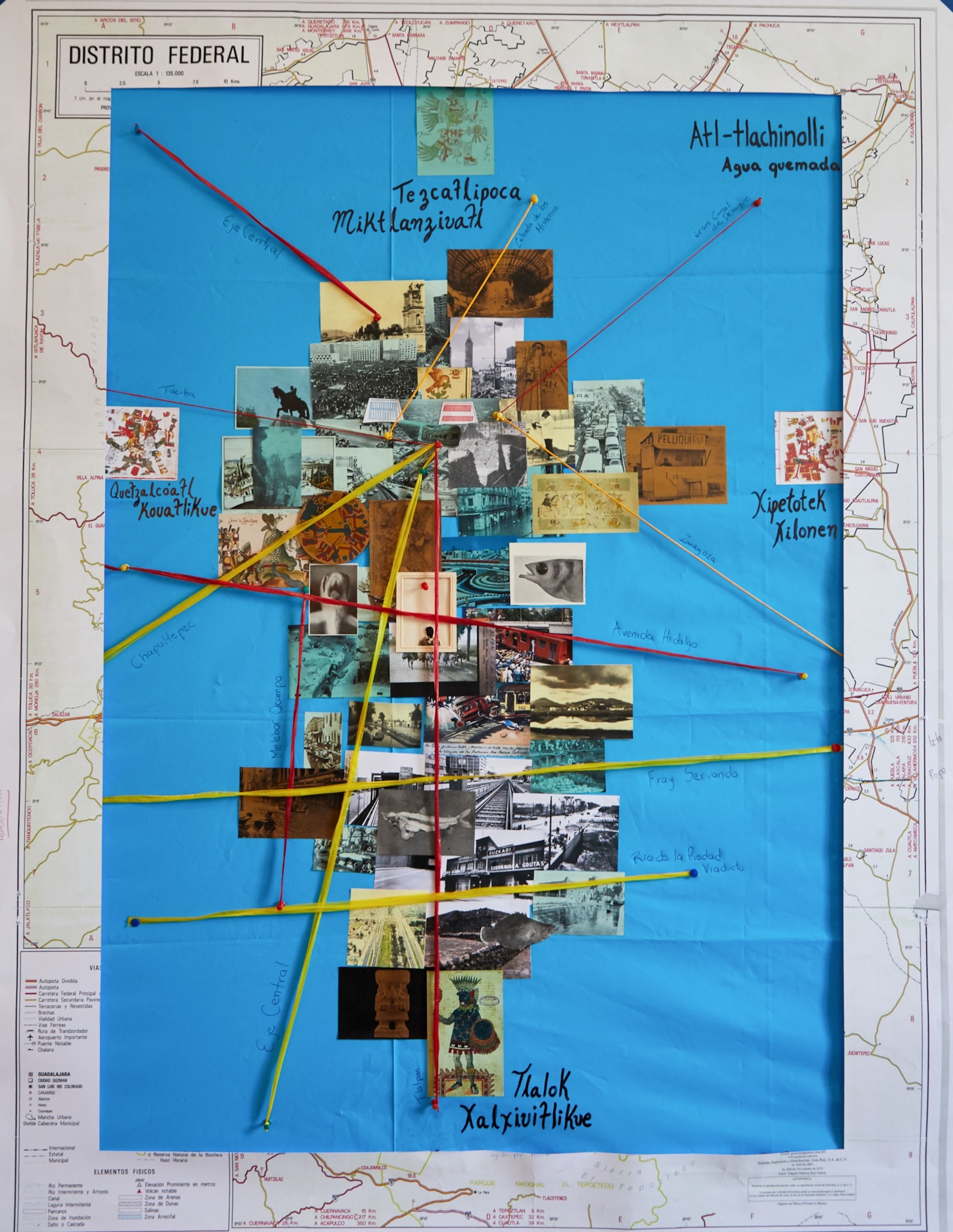

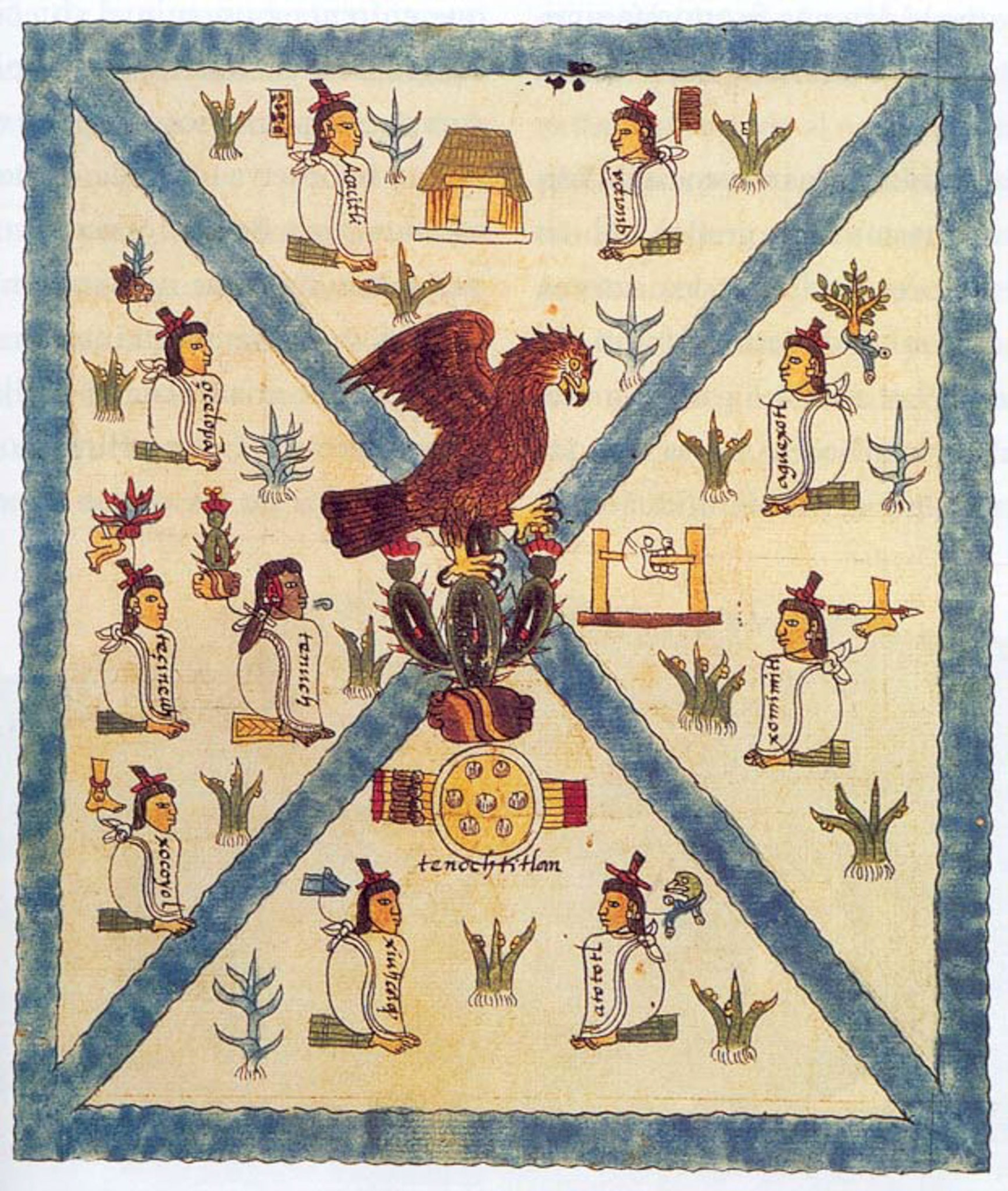

Still, there is an obvious logic to this stacking up of three major commemorations in succession. In the shorthand narrative of the nation, Mexico began to take shape around seven hundred years ago, when Indigenous migrants arrived in the Valley of Mexico and spotted an eagle devouring a serpent on an island in the middle of a lake—a scene memorialized today on the Mexican flag. Five hundred years ago, however, the nation was temporarily hijacked by Spain; and 200 years ago, it was finally—and triumphantly—restored.

New traditions and meanings

Meanwhile, out in the streets of Mexico, men and women continue to grapple with such historical milestones in their own ways, creating new traditions and meanings. This process is perhaps most evident at the small plaza of the “Tree of the Victorious Night.” Even though a fireworks accident in 1980 reduced the cypress to a burnt stump, it continues to attract visitors and invite reinterpretation.

On a recent day of plaza festivities in late June, a community organizer named Amalia Rosas offered a workshop on pre-contact foods. In an era when Mexicans suffer from some of the highest rates of obesity and diabetes in the world, Rosas exhorted attendees to give up processed meals and return to beans, squash, corn, and other healthful foods of our pre-Columbian ancestors.

A new mural was also unveiled in the plaza, depicting Spaniards fleeing the island-city of Tenochtitlan and making Indigenous porters carry heavy loads while the conquistadors themselves try to fend off attacks from Aztec warriors. “Cuitláhuac unleashed the offensive”—the accompanying text explains—as they [the Spanish] fled loaded with gold.”

Yet other Mexicans remain skeptical. During one of my visits, I watched an elderly couple milling about the tree stump. While the man took pictures of the stump with charred limbs sticking up, the woman read the new sign characterizing the site as a place of victory and happiness. Then she wistfully commented, to no one in particular: “History has been manipulated so much.”