Nikumaroro Island, Kiribati — Early in the morning on the last day of the expedition to find Amelia Earhart’s plane, the crew of the E/V Nautilus pulled Hercules, a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), out of the ocean. As Hercules streamed water onto the deck, Robert Ballard, the chief scientist on the expedition, went to check the last samples that the ROV brought up. Nautilus was scheduled to leave Nikumaroro for Samoa in an hour.

Donning black plastic gloves, Ballard slid a container out of the front of the ROV. Inside the seawater-filled bin was a laptop-size silver sheet and a crumbling black fragment that was part of something that looked like a barrel.

Ballard examined the items in the ship’s lab. The black fragment wasn’t aluminum so it couldn’t come from Earhart’s Lockheed Electra 10e. The silver sheet was more promising, especially since it appeared to have rivet holes. “It sure looked like aluminum underwater,” said Megan Lubetkin, a member of Nautilus’s science crew.

Ballard picked up the piece. “It’s not her plane,” he said. “It bends too much.”

This was a fitting end to what in many respects was a successful expedition (filmed by National Geographic for a two-hour special airing October 20). Something intriguing was recovered from the ocean floor with technology beyond any that had ever been used in the search for Amelia Earhart. Yet it wasn’t what Ballard and his team were looking for.

Ballard was drawn to this uninhabited island by evidence collected by the International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR). Based on Earhart’s last message and radio signals after she disappeared, the group believes that Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan may have landed on Nikumaroro in 1937 after they couldn’t find tiny Howland Island, the next stop on her world flight.

The theory goes that Earhart set down during low tide on the reef that surrounds Nikumaroro. After a few days, the tide lifted the plane off the reef, where it was dashed to bits—or where it floated for a while, then sank to the depths.

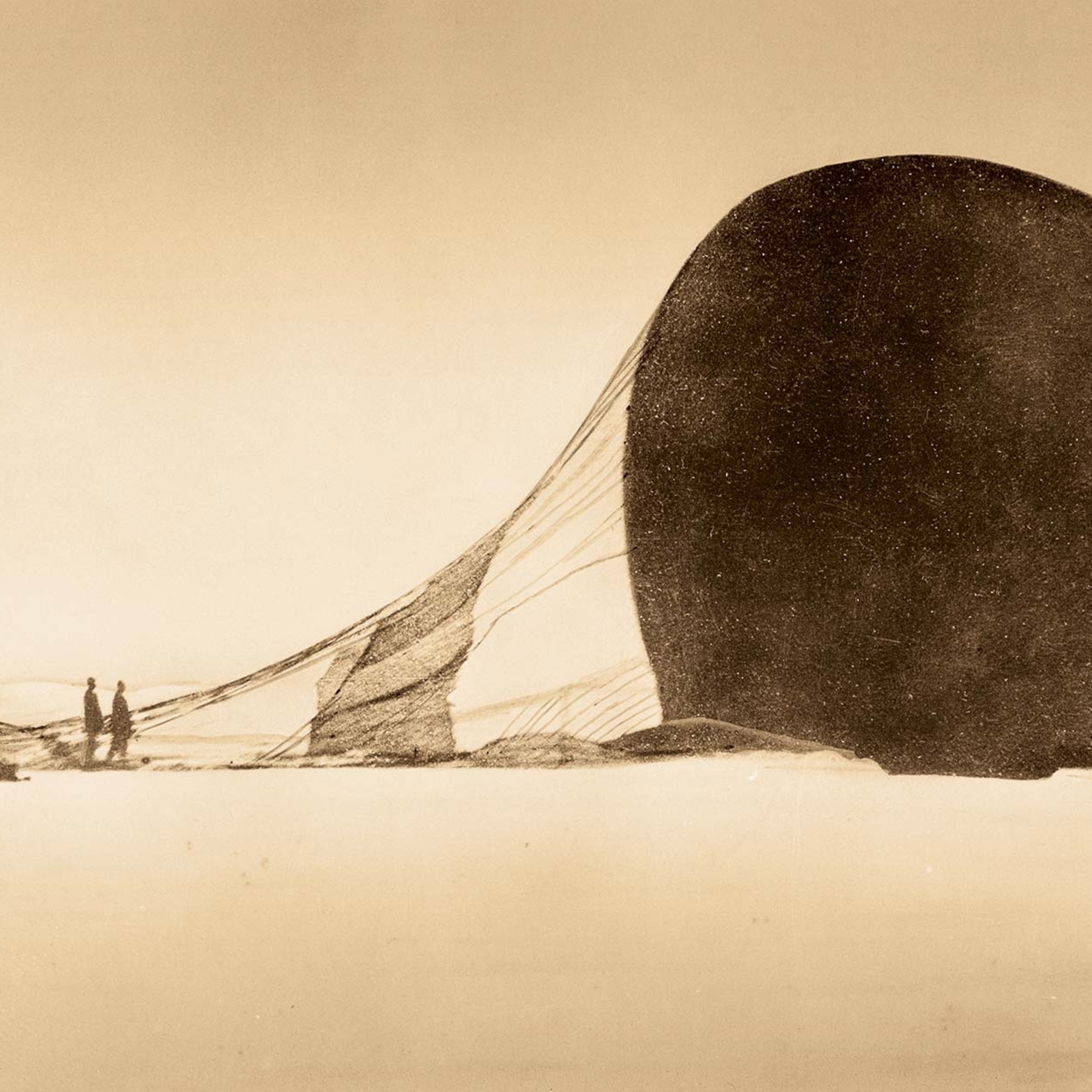

TIGHAR pinpoints the northwest side of the island as the site of the plane’s landing, where a ship called the S.S. Norwich City wrecked in 1929 and where the island’s lagoon opens to the sea in high tide. Three months after Earhart and Noonan’s disappearance, a British officer scouting the island for colonization took a photograph of the shipwreck—various analysts claim that a blurry shape to the left of it could be the Electra’s landing gear. People who lived on the island after it was colonized later told TIGHAR investigators that they had found aluminum wreckage near the lagoon’s entrance.

That northwest segment—from the lagoon’s opening to the island’s tip—became the expedition’s main search zone. “The goal is to find it in the primary place,” Ballard said midway through the expedition, “or to prove it’s not there.”

To do that, Ballard, a geologist, had to get to know Nikumaroro. He sent the ship five times around the island, which is four-and-a-half miles long, to map with multibeam sonar. He sent the autonomous surface vehicle (ASV) around the island twice to map the shallower areas close to the reef. He sent drones flying over the island to peer into the water where the surf breaks over the reef. He sent Argus, another ROV, into deeper water to do side scan sonar. And he sent both Argus and Hercules around the island to look for airplane wreckage with their cameras, which are monitored by his science team standing round-the-clock watches. “We did the whole enchilada,” says Ballard. “That’s total coverage.”

What he learned is that Nikumaroro is a tiny island at the peak of a massive seamount. It drops down to the ocean floor in a series of steep cliffs and ramps, most dramatically in the primary search zone. And like a mountain’s streams, chutes funnel debris down the slopes. Those chutes collect wreckage.

Hercules and Argus combed the chutes from top to bottom. Below the wreck of the Norwich City, the ROVs illuminated propellers, boilers, and other bits of ship for the watching science team. "I’ve learned a tremendous amount from the Norwich City” about how objects drain off the reef, says Ballard.

It was a different story in the primary search zone, the site of the supposed landing gear in the photo. “If the plane was up there, pieces would be moving down slope,” says Ballard, but the ROVs and the watching scientists found nothing.

You May Also Like

“We visually examined 100 percent of the island down to 750 meters [2,400 feet] and did not see evidence of the plane,” says Ballard. “We did 100 percent of the primary zone visually down to 900 meters [3,000 feet].”

No plane.

Ballard is not disappointed in this result. "This has been fun,” he says. “It called upon everything we’ve got.”

Island research and bone analysis

And he doesn’t consider the search to be over. Indeed, after this expedition, Nautilus is heading to Howland and Baker islands to map the waters off of these U.S. Territories for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Perhaps something will be discovered off the shore of the island where Earhart intended to land.

Ballard doesn’t plan on returning to Nikumaroro unless the land team finds definitive evidence that Earhart and Noonan perished there. Yet he already knows where he’d search if he did go back to the island: Beaches further south where it’s flat enough to land and the underwater topography is much smoother—perfect for sonar, he says.

That may happen sooner than expected. In 1940 a colonial administrator found bones, including a skull, on Nikumaroro, and sent them to Fiji, where they were lost. At the time, there was some speculation that the bones were Earhart’s. An expedition land team led by National Geographic Society archaeologist Fredrik Hiebert may have found fragments of the skull in the Te Umwanibong Museum and Cultural Centre in Tarawa, Kiribati.

According to Erin Kimmerle, a forensic anthropologist at the University of South Florida, the skull belonged to an adult female. “We don’t know if it’s her or not but all lines of evidence point to the 1940 bones being in this museum,” she says. They’ll know more when the skull has been reconstructed and its DNA tested, which should happen in the next few months.

This, too, is a fitting end to an Earhart expedition. Just when it seems to be over, a tantalizing clue appears to lure the searchers onward.