Why astronaut Victor Glover still believes in moon shots

The first Black person to clock a long-duration stay on the International Space Station, Glover is now aiming for the dark side of the moon. And he wants us all to keep reaching further.

When Victor Glover traveled to space for the first time, he felt like he was in two places at once. In 2020, as the flight engineer and a crew member of NASA’s Expedition 64/65 to the International Space Station, Glover scanned the instrument panel, checking the speed and altitude and the vehicle’s ground coordinates during the nearly nine-minute rocket ascent into weightlessness. But another part of him looked out the window, beholding planet Earth in its blue entirety, marveling at the heights he’d climbed. He was in outer space and was nearly out of body, at a time when people in many parts of the world were under a pandemic quarantine. If ever a symbol emerged of freedom in exploration, of pushing beyond human limits, this was it.

Now Glover is again preparing to travel to space, but this time farther than humans have ever traveled before. For the upcoming mission known as Artemis II, currently scheduled for April 2026, NASA will send a crew of four astronauts on a loop around the dark side of the moon and back; they’ll go 280,000 miles away from Earth, and more than 5,000 miles beyond the moon. And with NASA’s subsequent Artemis III mission, there are plans for humans to tread the moon’s surface for the first time in 50 years, this time on the never before visited south pole—all with the long-term goal of establishing a lunar settlement that would serve as a pit stop on the much longer trip to Mars.

“We still call great human accomplishments moon shots,” Glover says. “In the entire history of human experience, from the earliest recordings that we have on cave walls and chipped into stones, we’ve only sent a handful, a blip of people, away from the Earth. Even the ones living in low earth orbit, like when I lived on the space station, you’re only 250 miles away.” Glover believes that lunar exploration makes every person on the planet look up. “Our eyes are lifted,” he says. “Our hearts are lifted. And that to me, that collective inspiration, that collective support, and just something that unifies people—humanity deserves that.”

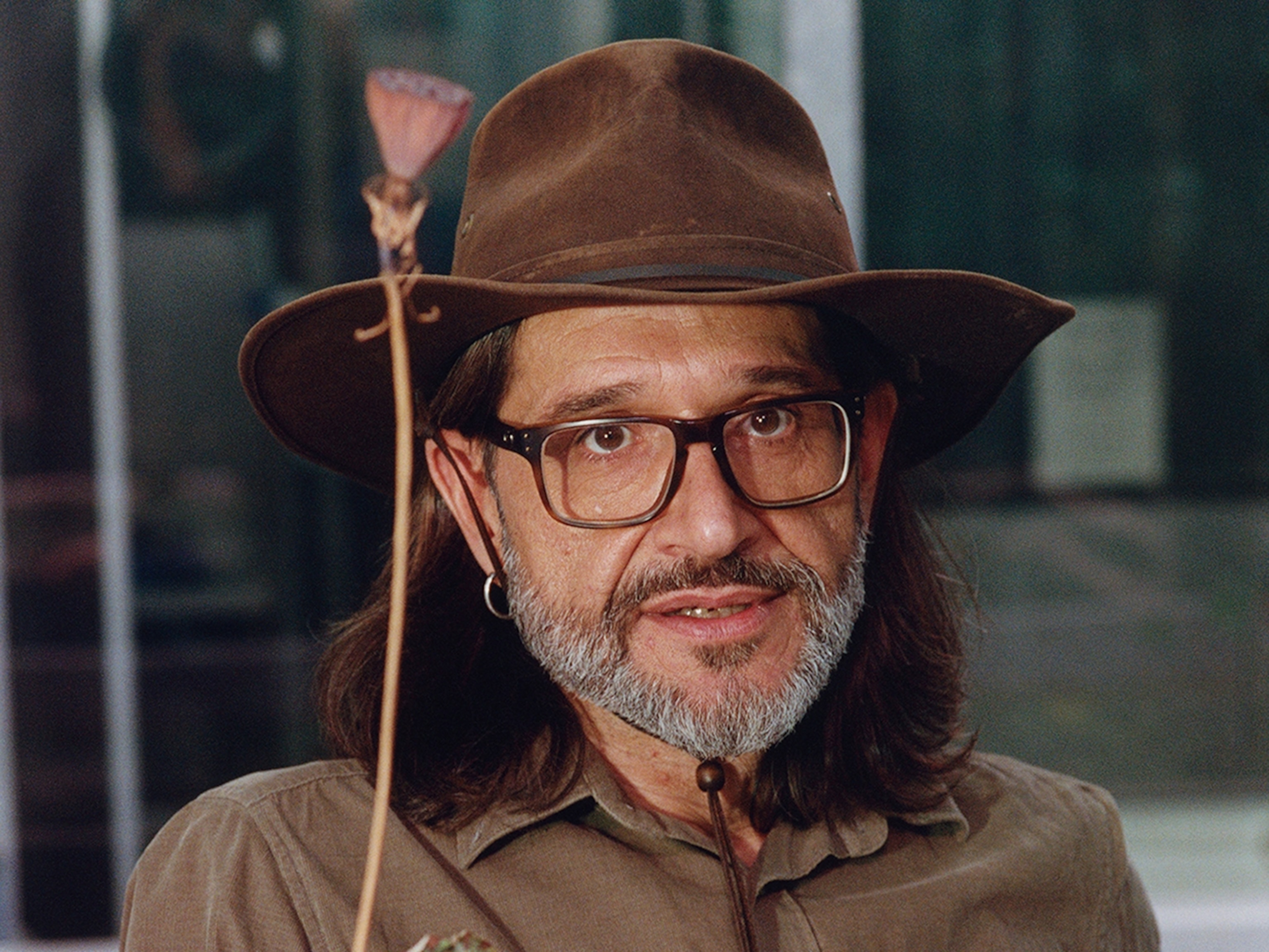

In many ways, Victor Glover fits the mold of people NASA sends to space. Like Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, Glover had spent years as a fighter pilot when NASA tapped him to become an astronaut in 2013. Glover even looks like a fighter pilot, in the Hollywood sense at least—handsome and square-jawed, with an athletic build held over from his days as a college football player and wrestler. But over the years, just 5 percent of NASA’s astronauts have been Black—17 out of more than 350 that the agency has sent to space. With Glover’s 168-day mission to the International Space Station in 2020, he became the first African American, and the first Black person from any part of the world, to have a long-duration stay on the station.

Glover’s trip came on the heels of a racial reckoning in the United States, but being a leader wasn’t something he considered, at least not in the beginning. “I actually chose to just keep it out of mind,” Glover says. “I asked NASA to not focus on that, to focus on the mission and the entire crew and what we were doing and why we’re doing it. Because at the end of the day, my real thoughts are, Don’t mess this up. Let me go up there and do my job and then come back.” When he did come back, he began to sense the weight of his accomplishment. In a conversation with Vice President Kamala Harris, “She said, I think it’s really important that we don’t just focus on the first—that we make sure that there’s a second and a third and a fourth.” And there have been. Multiple Black astronauts have lived on the space station since Glover’s mission. “I think that’s righteous,” he says.

On the ground, Glover has emerged as a leader and public figure, working with young people to encourage them to pursue STEM education. “I take that very seriously, trying to talk to young kids and encouraging them to just do their best, be growth-minded, that whatever they want to do, they can accomplish it,” says Glover, the first in his family to get a college degree. “I know we live in a country where we can see great things and great riches, but then also some of us live in abject poverty. And those same kids need to know they can do anything.”

The Artemis II mission promises to thrust Glover even farther into the realm of heroes. And he seems ready to take that on, in his body, maybe out of his body, on Earth and in outer space. “There’s going to be this really interesting time when we go behind the moon for 45 minutes,” he says. “We’re going to be out of communication with the whole rest of humanity. The four of us are going to be in that spacecraft together, but we cannot see or talk to the Earth and the Earth cannot see or talk to us.” Glover would love to share this message: There are conflicts going on around the world, the ones we hear about in the news and the ones we don’t. For the 45 minutes that humans are on the other side of the moon, what if we could pause. “Just wait until we get back in communication so that all of us can celebrate,” he says. “If we could have a 45-minute pause, what does that mean?” And here Glover himself pauses in contemplation. “There is a moment here that we can use to make things better for everybody.”