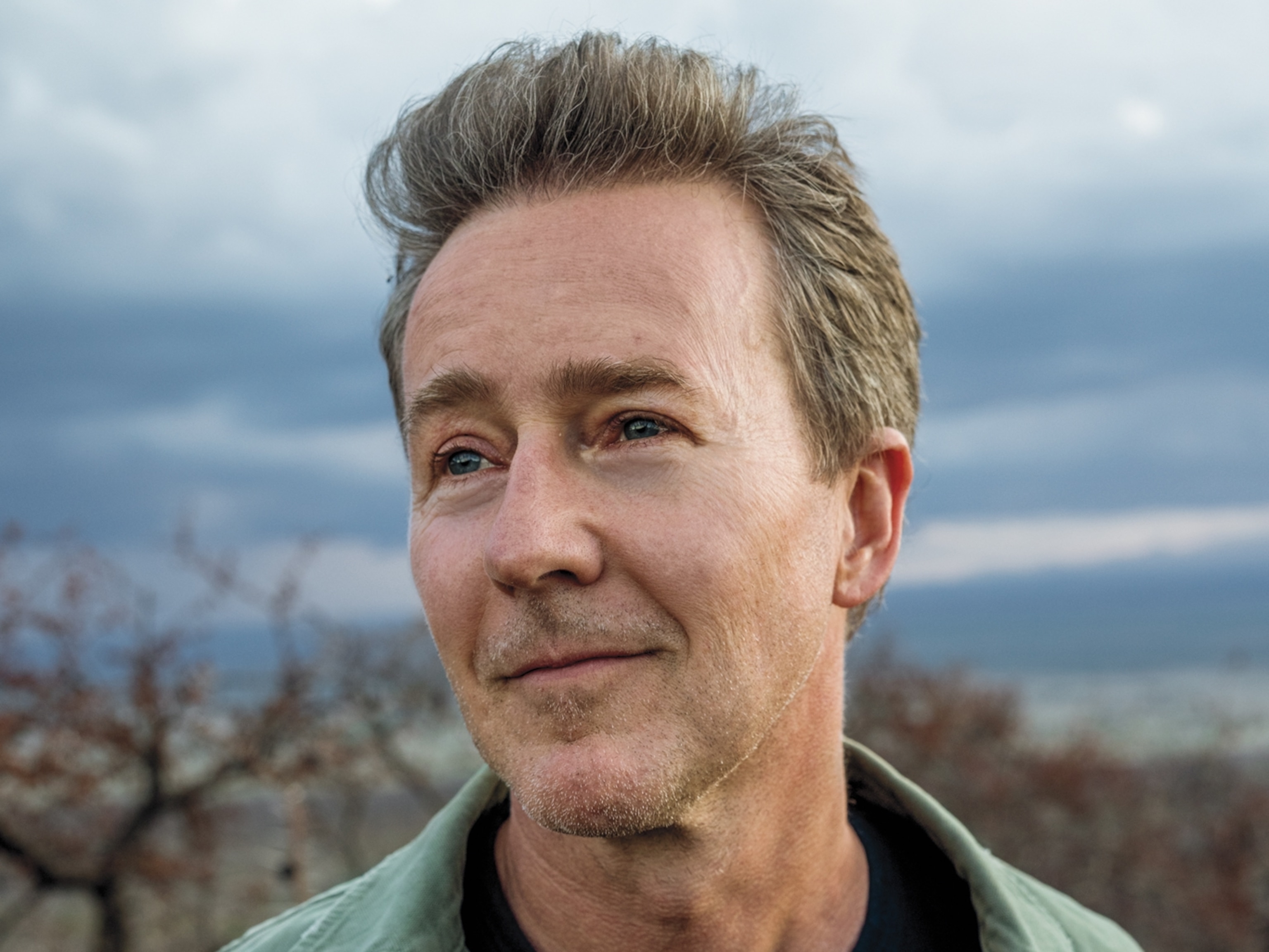

Yvon Chouinard on why he gave away Patagonia to save the planet

He reshaped the sportswear industry and became a billionaire. Then he did something even more impressive. What’s driving Yvon Chouinard? “It’s not an ego thing. I’ll be dead in a few years anyway.”

Yvon Chouinard laughs when he tries to remember the oldest piece of gear he owns. Perhaps it’s a piton he forged in the late 1950s, after he taught himself blacksmithing and started Chouinard Equipment, Ltd.? Or maybe it’s one of the rugged rugby shirts his next company, Patagonia, made for climbing? Possibly the “fleece” jacket prototype Patagonia built using toilet-seat-cover fabric, which has since become an outdoors icon?

“Almost everything I have is old,” says Chouinard, 86, grinning. “I use everything until it completely falls apart.” The Patagonia founder glances around the office of his Wyoming ranch—a pinewood house with a view of the Tetons that he and his friends built in 1976—then raises his hands to show that the sleeves of his faded plaid shirt are all in tatters. “My whole life has been pretty simple, really. I’m not a consumer.”

This may sound surprising, even hypocritical, from the founder of a company with consistent annual sales of a billion dollars. But Chouinard has long insisted he did not start Patagonia to turn a profit. “I have a living,” he told the New Yorker in 1977, “and that’s all I want out of it.” Nearly half a century later, in September 2022, he backed up that claim, stunning the business world by announcing he was giving away the three-billion-dollar company, with 2 percent of its shares going to a trust that helps guide Patagonia's social good mission and the other 98 percent to a newly created nonprofit, the Holdfast Collective, which uses the funds to advocate for environmental causes. “Earth,” Chouinard wrote on Patagonia’s website, “is now our only shareholder.”

“After you’re making enough money to support yourself, what’s the reason to stay in business?” he asks with a shrug. “Is it a responsibility for the employees that are still there to make more money or to do something good? We are doing good work and good things with our profits. That’s the real reason to keep going. It’s not an ego thing. I’ll be dead in a few years anyway.”

Chouinard’s decision to donate the company stemmed in part from his inclusion on a Forbes list of billionaires. He’d never seen himself that way, and the perception rankled. Without Patagonia, he could live like the man he felt himself to be—an octogenarian cowboy on a Western ranch with $60,000 a year, driving a 1987 Toyota Corolla and wearing frayed flannel.

For Patagonia, there are, of course, benefits to doing well as a business, admits Kris Tompkins, Patagonia’s transformative first CEO and one of Chouinard’s closest confidantes. “We want to be a successful company, because if you’re not, nobody will listen to you. But he would be as happy living under a bridge, or out of a van surfing God knows where, as being a wealthy man. That is the genius of Yvon.”

He beams when he talks about his father, a hardscrabble French Canadian jack-of-all-trades named Gerard, who moved his sizable family from Maine to California soon after World War II. He would trawl neighborhood trash cans, straightening discarded nails and salvaging tossed-off string; when the sum on the electric bill shocked him, he scaled the utility pole and rewired the system, so he no longer paid for anything.

Chouinard endured high school by resuscitating every bit of a 1940 Ford sedan, which he drove east to climb in Wyoming’s Wind River Range. “I was a dirtbag climber, and I got my dirtbag philosophy from my dad,” Chouinard says. “I had no money whatsoever. I was eating cat food, ground squirrels. I would sneak into yards to steal fruit.”

He has since climbed on every continent, and these days he finds it’s the sport he truly misses. (“My balance is shot to hell,” he sighs.) Still, alpinism’s visceral connection with the landscape made him realize long ago the irreparable ways humans change the world, even when scarring stone for sport. For six decades, he has striven in business to do less harm, an imperfect and unsteady process. Minimizing waste has been central to the mission, with Patagonia aiming to produce items that can last for a lifetime—or be fixed if they break, an anomaly in an era of planned obsolescence. He intends to maximize resources, not profits.

His approach comes from a conviction that “Patagonia is not a sustainable company,” he says. “There’s no such thing. I look at our philanthropy as not charity but as the cost of doing business, of using nonrenewable resources. Once you recognize that, you want to do something.”

Chouinard constantly references his pessimism. He is convinced, for instance, that the climate crisis cannot be solved until people find their spiritual connection with nature, as he did on Wyoming’s peaks and Yosemite’s walls. He believes public companies will never choose true sustainability over shareholder gains. But he counters that doubt with an idealism about what an individual can do with the right resources at their disposal—in his case, one of the world’s biggest outdoor brands. “When people say they believe in climate change but don’t do anything, they don’t really believe in it,” Chouinard says, ticking off explanations for inaction, from feelings of powerlessness to the supposed promise of technological salvation. “But the consequences are so grim, you can’t help but get involved.”

He’s more active in Patagonia’s operations now, he says, than when he divested himself from it two years ago. That’s because he needs to make sure the company can function in perpetuity if it’s going to have any chance of fulfilling his audacious mission statement: “to save our home planet.”