In her music, Björk is unconstrained. As an activist, she wants to be hyperpragmatic.

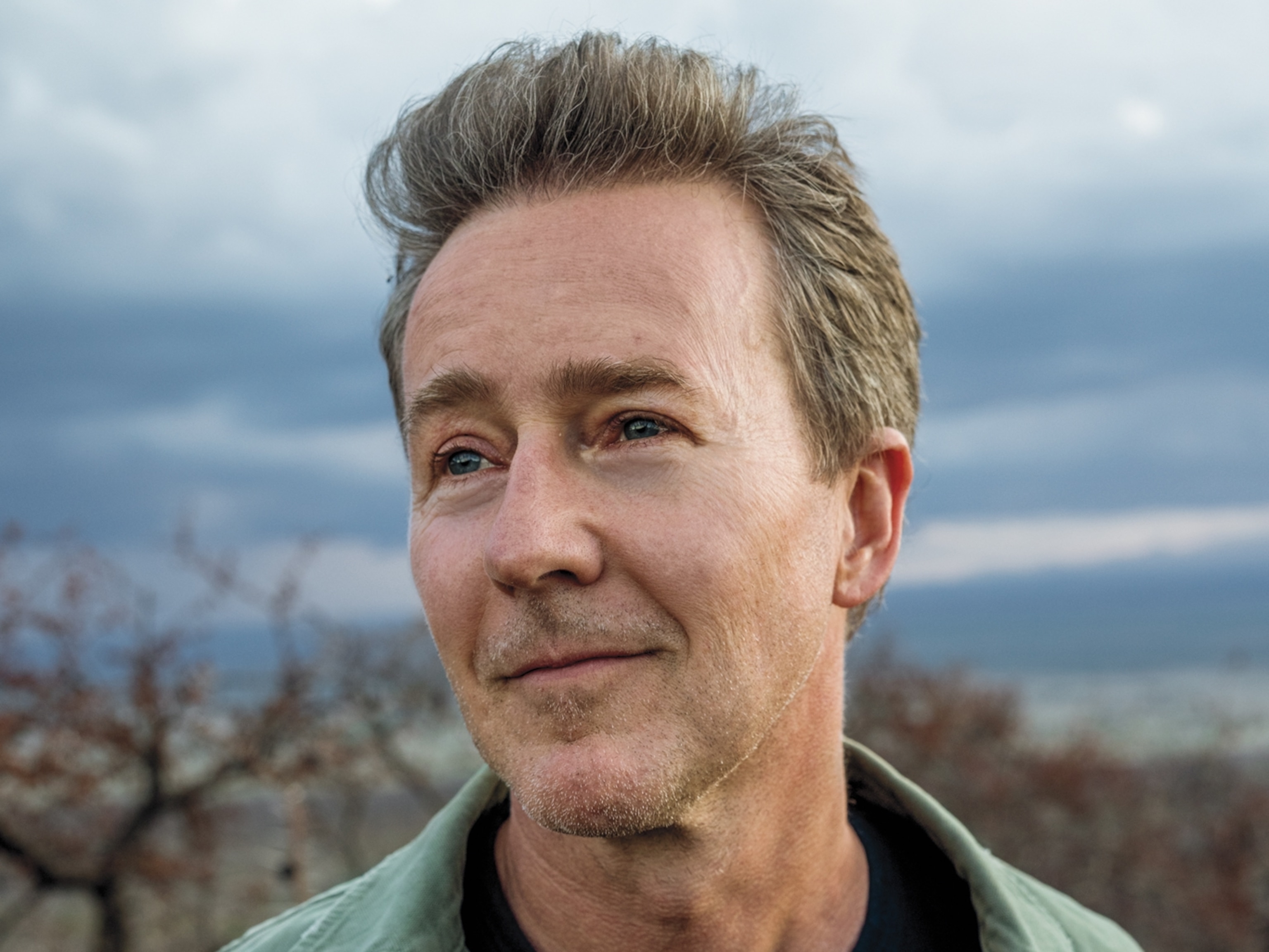

Why the otherworldly Icelandic artist believes in chasing achievable conservation goals. “I try to pick one thing that I will fight quite hard for.”

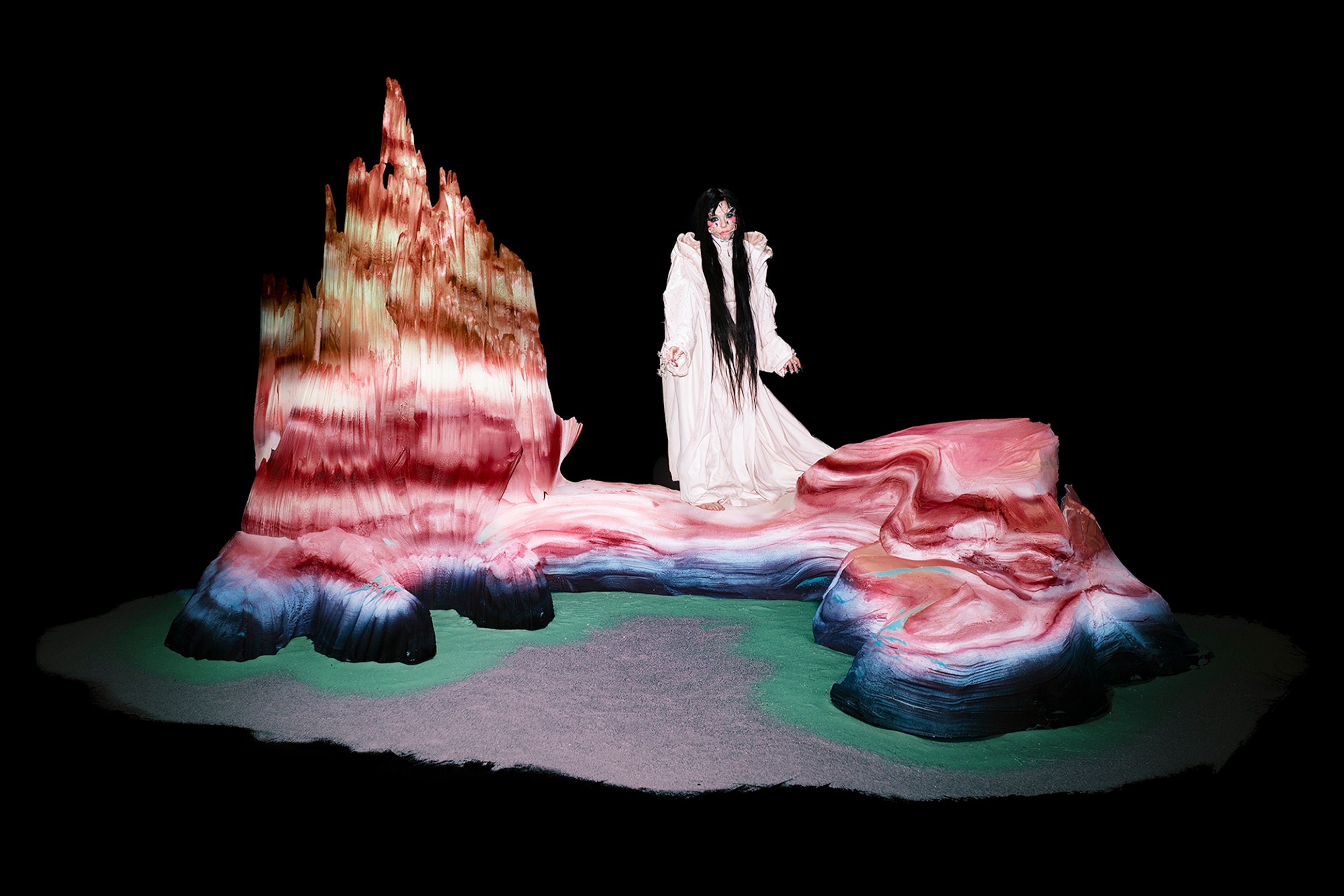

Björk always seems to inhabit an alternate universe—a dreamlike space of the highest creative ambition, free from the constraints that govern mere mortals. Which makes it all the more jarring when she injects her work with a dose of cold reality. In January she released a concert film shot during her recent Cornucopia tour. The show featured signature Björk flourishes, including expansive arrangements of Iceland’s Hamrahlíð Choir; giant, psychedelic projections of fungi; and the flashing of an environmental manifesto making an explicit appeal to the most urgent issue of our time: “The Paris climate accord is a modern utopia impossible to imagine, but overcoming our environmental challenges is the only way we can survive.”

Over Zoom one day last winter, she explained what she was getting at—namely a reframing of what’s possible. “When we look at the list of [goals in the Paris climate accord], it looks absolutely unreachable,” she says. “I think what we have to do is set different goals that are reachable.”

Björk is calling in from Paris, where she recently installed another manifesto in the escalators at the iconic Centre Pompidou. And while her artistic aims have consistently been lofty, her environmentalism is grounded in practical concerns. She exists on the most rarefied plane that a pop star can reach but keeps a careful eye on the scale of her chosen causes. “Every other year I try to pick one thing that I will fight quite hard for,” she says. “But I try to pick something where it’s actually possible to overturn. It’s big enough that it can matter but small enough that you can make a change.”

For the past two years, Björk, 59, has poured herself into the fight against commercial salmon farms in her native Iceland. After a hole in one farm’s pens allowed thousands of salmon to escape, there’s now concern that those fish may breed with native species or pass along diseases and parasites, creating a potential ecological nightmare. “Sometimes it’s been difficult to bridge a gap between Gen Z vegans and, like, farmers who kill sheep every autumn to eat,” she says. “But on this fish-farming project, everyone is united.” To bring global awareness to the issue, she took an unreleased song out of her archive and recruited Rosalía, the Spanish pop star, to record vocals for it. Proceeds from the song, titled “Oral,” are now supporting several ongoing lawsuits against the commercial fisheries. “It’s a marathon,” Björk says of the litigation. “And we are hoping that we will win the cases, and we can put them online for other countries to use.”

Björk still counts the island nation of her birth (population 383,000) as her home base. She grew up with a fiercely principled, antiestablishment mother who, in 2002, went on an 18-day hunger strike to protest plans to build an aluminum smelting operation and a power plant in the Icelandic highlands. Björk’s heritage is central to her environmental concerns, which have been increasingly enmeshed with her broader artistic project. “Every time I do something in Iceland, I always reach out to the environmental groups. We meet in my living room for coffee,” she says.

For decades, she’s been a globally beloved visionary who can sell out arenas, but she still operates with the spirit and principles of an indie act from the nineties: “I’m like an old punk, so I never receive money from anyone,” she tells me. This constitutional independence means that she usually rejects requests for commissioned works. But when the curators at the Pompidou asked her, last year, to create a version of her environmental manifesto for the museum, she recognized an opportunity to bridge the pillars of her creative, political, and technological sensibilities. Along with her own vocals, and with the help of AI software, the piece featured snippets of sound from endangered or extinct animals. “I give them the microphone. They repeat all the words with me,” she explains. She immersed herself in field recordings with animals. “At first, I cast the net quite wide. But then I ended up choosing animals that are most similar to the human voice, that are endangered or extinct,” she says. This list included the Hawaiian crow, the orangutan, and rare species of dolphins. At one point, she spent a full week listening to flocks of birds taking off in different parts of the world to figure out “which was the most ecstatic.”

As part of the Pompidou commission, Björk asked the museum’s curators to gather young environmental activists to pursue another “reachable” cause: She wants them to petition French president Emmanuel Macron to ban bottom trawling in the country’s protected waters. It’s another seemingly modest goal with the potential to make a tangible impact. “I try to make the best of the fact that I come from a very small country that is very untouched,” she says. “Instead of doing 10 things, [I try to] do one thing properly and follow it all the way to the end … not just be a face on some campaign and show up at a cocktail party and go home and not know what’s going to happen.”